Articles 2015 年 6 月 第 48 巻

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Want to Start a Revolution? Gore, Dayo, Theoharis, Jeanne, Woodard, Komozi

Want to Start a Revolution? Gore, Dayo, Theoharis, Jeanne, Woodard, Komozi Published by NYU Press Gore, Dayo & Theoharis, Jeanne & Woodard, Komozi. Want to Start a Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. New York: NYU Press, 2009. Project MUSE., https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/10942 Access provided by The College Of Wooster (14 Jan 2019 17:31 GMT) 4 Shirley Graham Du Bois Portrait of the Black Woman Artist as a Revolutionary Gerald Horne and Margaret Stevens Shirley Graham Du Bois pulled Malcolm X aside at a party in the Chinese embassy in Accra, Ghana, in 1964, only months after hav- ing met with him at Hotel Omar Khayyam in Cairo, Egypt.1 When she spotted him at the embassy, she “immediately . guided him to a corner where they sat” and talked for “nearly an hour.” Afterward, she declared proudly, “This man is brilliant. I am taking him for my son. He must meet Kwame [Nkrumah]. They have too much in common not to meet.”2 She personally saw to it that they did. In Ghana during the 1960s, Black Nationalists, Pan-Africanists, and Marxists from around the world mingled in many of the same circles. Graham Du Bois figured prominently in this diverse—sometimes at odds—assemblage. On the personal level she informally adopted several “sons” of Pan-Africanism such as Malcolm X, Kwame Nkrumah, and Stokely Carmichael. On the political level she was a living personification of the “motherland” in the political consciousness of a considerable num- ber of African Americans engaged in the Black Power movement. -

A History of African American Theatre Errol G

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-62472-5 - A History of African American Theatre Errol G. Hill and James V. Hatch Frontmatter More information AHistory of African American Theatre This is the first definitive history of African American theatre. The text embraces awidegeographyinvestigating companies from coast to coast as well as the anglo- phoneCaribbean and African American companies touring Europe, Australia, and Africa. This history represents a catholicity of styles – from African ritual born out of slavery to European forms, from amateur to professional. It covers nearly two and ahalf centuries of black performance and production with issues of gender, class, and race ever in attendance. The volume encompasses aspects of performance such as minstrel, vaudeville, cabaret acts, musicals, and opera. Shows by white playwrights that used black casts, particularly in music and dance, are included, as are produc- tions of western classics and a host of Shakespeare plays. The breadth and vitality of black theatre history, from the individual performance to large-scale company productions, from political nationalism to integration, are conveyed in this volume. errol g. hill was Professor Emeritus at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire before his death in September 2003.Hetaughtat the University of the West Indies and Ibadan University, Nigeria, before taking up a post at Dartmouth in 1968.His publications include The Trinidad Carnival (1972), The Theatre of Black Americans (1980), Shakespeare in Sable (1984), The Jamaican Stage, 1655–1900 (1992), and The Cambridge Guide to African and Caribbean Theatre (with Martin Banham and George Woodyard, 1994); and he was contributing editor of several collections of Caribbean plays. -

WARD, THEODORE, 1902-1983. Theodore Ward Collection, 1937-2009

WARD, THEODORE, 1902-1983. Theodore Ward collection, 1937-2009 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Ward, Theodore, 1902-1983. Title: Theodore Ward collection, 1937-2009 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1166 Extent: 1.5 linear feet (3 boxes) Abstract: Collection of materials relating to African American playwright Theodore Ward including personal papers, play scripts, and printed material associated with his plays. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Theodore Ward papers, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah. Theodore Ward plays, Play Script Collection, New York Public Library. Source Gift of James V. Hatch and Camille Billops, 2011 Custodial History Forms part of the Camille Billops and James V. Hatch Archives at Emory University. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Theodore Ward collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Theodore Ward collection, 1937-2009 Manuscript Collection No. 1166 Appraisal Note Acquired by Curator of African American Collections, Randall Burkett, as part of the Rose Library's holdings in African American theater. Processing Arranged and described at the file level by Courtney Chartier and Sarah Quigley, 2017. This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. -

158 Kansas History the Hard Kind of Courage: Labor and Art in Selected Works by Langston Hughes, Gordon Parks, and Frank Marshall Davis

Gordon Parks’s American Gothic, Washington, D.C., which captures government charwoman Ella Watson at work in August 1942. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 36 (Autumn 2013): 158–71 158 Kansas History The Hard Kind of Courage: Labor and Art in Selected Works by Langston Hughes, Gordon Parks, and Frank Marshall Davis by John Edgar Tidwell hen and in what sense can art be said to require a “hard kind of courage”? At Wichita State University’s Ulrich Museum, from September 16 to December 16, 2012, these questions were addressed in an exhibition of work celebrating the centenary of Gordon Parks’s 1912 birth. Titled “The Hard Kind of Courage: Gordon Parks and the Photography of the Civil Rights Era,” this series of deeply profound images offered visual testimony to the heart-rending but courageous sacrifices made by Freedom Riders, the bombing victims Wat the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, the energized protesters at the Great March on Washington, and other participants in the movement. “Photographers of the era,” the exhibition demonstrated, “were integral to advancing the movement by documenting the public and private acts of racial discrimination.”1 Their images succeeded in capturing the strength, fortitude, resiliency, determination, and, most of all, the love of those who dared to step out on faith and stare down physical abuse and death. It is no small thing that all this was done amidst the challenges of being a black artist or writer seeking self-actualization in a racially charged era. -

Manhattan, Kansas African American History Trail Self-Guided Driving

1 Manhattan, Kansas African American History Trail Self-Guided Driving Tour July 2020 This self-guided driving tour was developed by the staff of the Riley County Historical Museum to showcase some of the interesting and important African American history in our community. You may start the tour at the Riley County Historical Museum, or at any point along to tour. Please note that most sites on the driving tour are private property. Sites open to the public are marked with *. If you have comments or corrections, please contact the Riley County Historical Museum, 2309 Claflin Road, Manhattan, Kansas 66502 785-565-6490. For additional information on African Americans in Riley County and Manhattan see “140 Years of Soul: A History of African-Americans in Manhattan Kansas 1865- 2005” by Geraldine Baker Walton and “The Exodusters of 1879 and Other Black Pioneers of Riley County, Kansas” by Marcia Schuley and Margaret Parker. 1. 2309 Claflin Road *Riley County Historical Museum and the Hartford House, open Tuesday through Friday 8:30 to 5:00 and Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00. Admission is free. The Museum features changing exhibits on the history of Riley County and a research archive/library open by appointment. The Hartford House, one of the pre-fabricated houses brought on the steamboat Hartford in 1855, is beside the Riley County Historical Museum. 2. 2301 Claflin Road *Goodnow House State Historic Site, beside the Riley County Historical Museum, is open Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00 and when the Riley County Historical Museum is open and staff is available. -

The Vlakh-Bor™,^ • University of Hawaii

THE VLAKH-BOR™,^ • UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII-. n ■ ■ LIBRARY -' - .. ........__________________ Page Five HONO., T.H.52 8-4-49 ~ Sec. 562, P. L. & R. .U. S. POSTAGE Single Issue 1* PAID The Newspaper Hawaii Needs Honolulu, T. H. 10c $5.00 per year Permit No. 189 by subscription Vol. 1, No. 40 PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY May SMW Advertiser Does It Again! TH LABOR LOSES $100,000 BY LEGISLATIVE SLOTH "Red” Smew Is DamonDemos Solons Improve 29 Yews Old Protest Big WCL; Provide No Hike In 1 axes Staff Addition By STAFF WRITER Land that formerly cost own Working-people in Hawaii will ers in Damon Tract taxes of three be deprived of $100,000 rightfully cents per square foot has this year due them next • year, because the been assessed at 10 cents per square legislature failed to implement the foot, and as a result, a number improved Workmen’s Compensa of Damon Tract people are indig tionLaw by providing a staff ca- . nantly and actively protesting. pable of administering it. That , “The .increase,” says Henry Ko-. is the opinion of William- M. -Doug kona, Damon Tract resident who las of the Bureau of Workmen’s leads the movement, “is from 100 Compensation. v. ■ . to 400 per cent, varying with the The platforms of both parties number of improvements on the included statements approving ad place. The assessor says it’s be- ditions to the Bureau’s.very small . cause Damon Tract has become staff, no additions >were made, a - residential district. Before, it though some very substantial im was assessed as farming land.-” provements .were realized. -

Aberdeen, S.Dak.: Bakeries In, 282–300; Churches In, 256N3, 287

Copyright © 2019 South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. INDEX Aberdeen, S.Dak.: bakeries in, 282–300; churches Fall of Lillian Frances Smith: revd., 324, 326 in, 256n3, 287; historic district in, 283n3; hospital Amerikan Suomalainen, 267 in, 23; immigration to, 257, 259, 283–84; railroads Anarchy U.S.A. (film), 188 in, 282–83; schools in, 9, 23; and WWI, 1–31 Anderson, Timothy G.: book by, revd., 80, 82 Aberdeen American- News, 291, 293, 296, 297–98, Anderson, William: blog post by, 75–77 300 Anglo- Ashanti Campaign, 105n36 Aberdeen Daily American, 3–4, 20, 21, 290 Anishinaabe Indians, 183 Aberdeen Daily News, 289, 292 Anti- communism, 188, 193 Aberdeen Democrat, 288 Apache Indians, 87 African Gold Coast, 105n36 Appeal to Reason, 238–39 Agrarianism, 223, 236–37, 243 Arapaho Indians, 87 Agriculture, 201; farm size and income, 228, 234; Arikara Indians, 200n1, 201–15, 219 grasshopper plagues, 74, 220, 224, 243, 246; and Army- Navy Nurses Act of 1947, 8n12 Great Depression, 220–48; Laura Ingalls Wilder Artesian, S.Dak., 235 and, 59–60, 70–72; and WWI, 222 Arviso, Vivian, 178 Agriculture Adjustment Act of 1933, 240 Ascension Presbyterian Church (Peever), 306–7 Aid to Dependent Children, 241 Ashley, William Henry, 213 Akwesasne Notes, 187, 192 Ashley Island, 202, 211 Alcantara (Franciscan nun), 316 Assimilation, 147, 177 Alcoholism, 181, 196. See also Prohibition Assiniboine River, 200n1 Alexander, Benjamin: book by, revd., 329 Assiniboin Indians, 116n48 Alexander I, 284 Associated Press, 38, 39 Allen, Eustace A., 27 Augur, Christopher C., 160 Almlie, Elizabeth J., 301 Augustana Swedish Lutheran Church, 255, 272–76, Alway, R. -

A Bibliography of Plays Written by Black Americans: 1855 to the Present. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 14P.; Prepared at Eastern Illinois University

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 676 CS 201 568 AUTHOR Whitlow, Roger, Comp. TITLE A Bibliography of Plays Written by Black Americans: 1855 to the Present. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 14p.; Prepared at Eastern Illinois University EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *American Literature; *Bibliographies; *Drama; Higher Education; Negro Culture; *Negro Literature; Nineteenth Century Literature; Twentieth Century Literature ABSTRACT This 342-item alphabetized bibliography of plays by black Americans covers the period from 1855 to the present. Some of the playwrights and their works are Paul L. Dunbar's "Uncle Eph's Christmas," 1905; James V. Johnson and Bob Cole's "The Shoo-Ply Regiment," 1907; Lorraine Hansberry's "A Raisin in the Sun," 1959; James Baldwin'$ "Blues for Mr. Charlie," 1964; Ed Bullins' "In New england Winter," 1967; Le Roi Jones' (Isamu Amiri Baraka) "Dutchcan" and "The Slave," 1964; and Ossie Davis' "Purlie Victorious," 1961. Some of the plays included have never beer published. (SW) DEpaRTmENToc HEALTH EDUCATION WELFARE NATIONALtNStiTUTEOF IcOUCTION mr FIE% AA , ' WE I t. 14,1%. PE cp-% QC!, ...t% :Fc .:. h PO ti' .I 0, . oht, ...1'k,,,e` h- hFE ,: wr Pro Eti* OFF ( AL NA' '1- D.10.4 ., ' A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PLAYS WRITTEN BY BLACK AMERICANS: 1855 TO THE PRESENT 'PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPY. RIGHTED MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED Compiled by Roger Whitlow Roger Whitlow .. TO ERICAND ORGANIZATIONS OPERATING Assistant Professor of English UNDER AGREEMENTS WITH THE NATIONAL IN STITUTE OF EDUCATION FURTHER REPRO. Eastern Illinois University DUCTION OUTSIDE THE ERIC SYSTEM RE. QUIRES PERMISSION OFTHE COPYRIGHT Charleston, Tllinois 61920 OWNER Aldridge, Ira rrederick A GLANCE AT THE LIFE OF IRA FREDERICK ALDRIDGE. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 115 646 SP 009 718 TITLE Multi-Ethnic

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 115 646 SP 009 718 TITLE Multi-Ethnic Contributions to American History.A Supplementary Booklet, Grades 4-12. INSTITUTION Caddo Parish School Board, Shreveport, La. NOTE' 57p.; For related document, see SP 009 719 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$3.32 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Achievement; *American History; *Cultural Background; Elementary Secondary Education; *Ethnic Groups; *Ethnic Origins; *Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS *Multicultural Education ABSTRACT This booklet is designed as a teacher guide for supplementary use in the rsgulat social studies program. It lists names and contributions of Americans from all ethnic groups to the development of the United States. Seven units usable at three levels (upper elementary, junior high, and high school) have been developed, with the material arranged in outline form. These seven units are (1) Exploration and Colonization;(2) The Revolutionary Period and Its Aftermath;(3) Sectionalism, Civil War, and Reconstruction;(4) The United States Becomes a World Power; (5) World War I--World War II; (6) Challenges of a Transitional Era; and (7) America's Involvement in Cultural Affairs. Bibliographical references are included at the end of each unit, and other source materials are recommended. (Author/BD) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * via the ERIC Document-Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the qUa_lity of the original document. Reproductions * supplied-by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. -

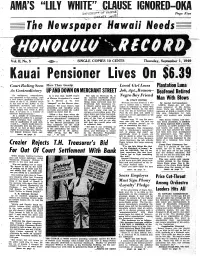

HONOLULU.Rtcord

AMA’S “LILY WHITE” CLAUSE IGNORED -OKA Of HAM • • Page Five ^The Newspaper Hawaii Needs HONOLULU.RtCORD. Vol. II, No. 5 SINGLE COPIES 10 CENTS Thursday, September 1, 1949 Kauai Pensioner Lives On $6.39 Court R uling Seen More Than Gossip: Local Girl Loses Plantation Luna As Contradictory UP AND DOWN ON MERCHANT STREET Job,Apt^Reason-- Deafened Retired “So ambiguous, contradictory, Is it true that 125,000 shares The talk on Merchant St. is Negro Boy Friend and uncertain is this ruling,” says of Matson Navigation Co. owned the reported $40,000,000 which a local lawyer, speaking of the' de the California and Hawaiian Re By STAFF WRITER Man With Blows cision of the U. S. District Court by C. Brewer & Co. were fining Corp, borrowed from the “dumped” on the Brewer plan Because her boy friend is a Ne By Special Correspondence in the case-of-the ILWU vs. the Prudential Life Insurance Co. gro—a soldier and a veteran of legislature, governor and others, tations? We hear there’s loud LIHUE, Kauai—An old Jap A reliable source says that this action in Germany in World War anese pensioner of the Koloa- “that it can be interpreted only grumbling and rumbling going money paid for two-thirds of II—Sharon Wiechel, 22, was fired by the judges who wrote it. Even on inside and outside the walled this year’s sugar crop now in Grove Farm was retired by the then, it is* open to a number of citadel on lower Fort St. from her job at American Legion company: at,$14.04 a month. -

Hall Johnson's Choral and Dramatic Works

Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wittmer, Micah. 2016. Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939). Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:26718725 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939) A dissertation presented by Micah Wittmer To The Department of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Music Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January, 2016 © 2016, Micah Wittmer All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Carol J. Oja Micah Wittmer -- Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939) Abstract This dissertation explores the portrayal of Negro folk culture in concert performances of the Hall Johnson Choir and in Hall Johnson’s popular music drama, Run, Little Chillun. I contribute to existing scholarship on Negro spirituals by tracing the performances of these songs by the original Fisk Jubilee singers in 1867 to the Hall Johnson Choir’s performances in the 1920s-1930s, with a specific focus on the portrayal of Negro folk culture. -

The Creation of Identity in the Radicial Plays of Langston Hughes

BLACK OR RED?: THE CREATION OF IDENTITY IN THE RADICIAL PLAYS OF LANGSTON HUGHES A dissertation submitted by Catherine Ann Peckinpaugh Vrtis In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama TUFTS UNIVERISITY May, 2017 ADVISOR: Downing Cless © 2017, Catherine Vrtis i ABSTRACT Langston Hughes, despite his reputation as the measure of an “authentic” black identity in art, was self-consciously performative in his creation of self through his writing. While this is hidden in most of his work due to his mastery of the tropes of “writing race,” the constructed nature of his public personae is revealed through his profound shift of artistic position, from primarily racially focused to primarily class oriented and Communist aligned, during the decade of the 1930s. As demonstrated by his radical works, Hughes’ professional identities were shaped by competing needs: to represent his sincere political beliefs and to answer the desires of his audiences. As he supported himself exclusively through his writing, Hughes could not risk alienating his publishers, but he was also not willing to support any ideology for profit. His radical plays, more so than his other Red writing, track Hughes’ negotiation of this tension during his Communist years. Hughes already had sympathies with the Communist cause when he broke with his patron, Charlotte Mason, at the beginning of the Great Depression, and instability of the period only deepened his radicalism. Freed from her expectations and in need of an audience, Hughes sharply shifted his public and artistic persona, downplaying his “Negro Poet Laureate” identity to promote his new Red one.