A Critical Analysis of the Black President in Film and Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Philanthropy Forum Conference April 18–20 · Washington, Dc

GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE APRIL 18–20 · WASHINGTON, DC 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference This book includes transcripts from the plenary sessions and keynote conversations of the 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference. The statements made and views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of GPF, its participants, World Affairs or any of its funders. Prior to publication, the authors were given the opportunity to review their remarks. Some have made minor adjustments. In general, we have sought to preserve the tone of these panels to give the reader a sense of the Conference. The Conference would not have been possible without the support of our partners and members listed below, as well as the dedication of the wonderful team at World Affairs. Special thanks go to the GPF team—Suzy Antounian, Bayanne Alrawi, Laura Beatty, Noelle Germone, Deidre Graham, Elizabeth Haffa, Mary Hanley, Olivia Heffernan, Tori Hirsch, Meghan Kennedy, DJ Latham, Jarrod Sport, Geena St. Andrew, Marla Stein, Carla Thorson and Anna Wirth—for their work and dedication to the GPF, its community and its mission. STRATEGIC PARTNERS Newman’s Own Foundation USAID The David & Lucile Packard The MasterCard Foundation Foundation Anonymous Skoll Foundation The Rockefeller Foundation Skoll Global Threats Fund Margaret A. Cargill Foundation The Walton Family Foundation Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation The World Bank IFC (International Finance SUPPORTING MEMBERS Corporation) The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust MEMBERS Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Anonymous Humanity United Felipe Medina IDB Omidyar Network Maja Kristin Sall Family Foundation MacArthur Foundation Qatar Foundation International Charles Stewart Mott Foundation The Global Philanthropy Forum is a project of World Affairs. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

1 Building Bridges: the Challenge of Organized

BUILDING BRIDGES: THE CHALLENGE OF ORGANIZED LABOR IN COMMUNITIES OF COLOR Robin D. G. Kelley New York University [email protected] What roles can labor unions play in transforming our inner cities and promo ting policies that might improve the overall condition of working people of color? What happens when union organizers extend their reach beyond the workplace to the needs of working-class communities? What has been the historical role of unions in the larger struggles of people of color, particularly black workers? These are crucial questions in an age when production has become less pivotal to working-class life. Increasingly, we've witnessed the export of whole production processes as corporations moved outside the country in order to take advantage of cheaper labor, relatively lower taxes, and a deregulated, frequently antiunion environment. And the labor force itself has changed. The old images of the American workingclass as white men residing in sooty industrial suburbs and smokestack districts are increasingly rare. The new service-based economy has produced a working class increasingly concentrated in the healthcare professions, educational institutions, office building maintenance, food processing, food services and various retail establishments. 1 In the world of manufacturing, sweatshops are coming back, particularly in the garment industry and electronics assembling plants, and homework is growing. These unions are also more likely to be brown and female than they have been in the past. While white male membership dropped from 55.8% in 1986 to 49.7% in 1995, women now make up 37 percent of organized labor's membership -- a higher percentage than at any time in the U.S. -

World Latin American Agenda 2016

World Latin American Agenda 2016 In its category, the Latin American book most widely distributed inside and outside the Americas each year. A sign of continental and global communion among individuals and communities excited by and committed to the Great Causes of the Patria Grande. An Agenda that expresses the hope of the world’s poor from a Latin American perspective. A manual for creating a different kind of globalization. A collection of the historical memories of militancy. An anthology of solidarity and creativity. A pedagogical tool for popular education, communication and social action. From the Great Homeland to the Greater Homeland. Our cover image by Maximino CEREZO BARREDO. See all our history, 25 years long, through our covers, at: latinoamericana.org/digital /desde1992.jpg and through the PDF files, at: latinoamericana.org/digital This year we remind you... We put the accent on vision, on attitude, on awareness, on education... Obviously, we aim at practice. However our “charisma” is to provoke the transformations of awareness necessary so that radically new practices might arise from another systemic vision and not just reforms or patches. We want to ally ourselves with all those who search for that transformation of conscience. We are at its service. This Agenda wants to be, as always and even more than at other times, a box of materials and tools for popular education. latinoamericana.org/2016/info is the web site we have set up on the network in order to offer and circulate more material, ideas and pedagogical resources than can economically be accommo- dated in this paper version. -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Dissertation As a Partial

Distribution Agreement In presenting this dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non- exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this dissertation. Signature: ____________________________ ______________ Michelle S. Hite Date Sisters, Rivals, and Citizens: Venus and Serena Williams as a Case Study of American Identity By Michelle S. Hite Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts ___________________________________________________________ Rudolph P. Byrd, Ph.D. Advisor ___________________________________________________________ Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Ph.D. Committee Member ___________________________________________________________ Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: ___________________________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School ____________________ Date Sisters, Rivals, and Citizens: Venus and Serena Williams as a Case Study of American Identity By Michelle S. Hite M.Sc., University of Kentucky Rudolph P. Byrd, Ph.D. An abstract of A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Emory University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts 2009 Abstract Sisters, Rivals, and Citizens: Venus and Serena Williams as a Case Study of American Identity By Michelle S. -

Mr. Jeffery Morehouse Executive Director, Bring Abducted Children Home and Father of a Child Kidnapped to Japan

Mr. Jeffery Morehouse Executive Director, Bring Abducted Children Home and Father of a Child Kidnapped to Japan House Foreign Affairs Committee Monday, December 10, 2018 Reviewing International Child Abduction Thank you to Chairman Smith and the committee for inviting me here to share my expertise and my personal experience on the ongoing crisis and crime of international parental child abduction in Japan. Japan is internationally known as a black hole for child abduction. There have been more than 400 U.S. children kidnapped to Japan since 1994. To date, the Government of Japan has not returned a single American child to an American parent. Bring Abducted Children Home is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the immediate return of internationally abducted children being wrongfully detained in Japan and strives to end Japan's human rights violation of denying children unfettered access to both parents. We also work with other organizations on the larger goal of resolving international parental child abduction worldwide. We are founding partners in The Coalition to End International Parental Child Abduction uniting organizations to work passionately to end international parental kidnapping of children through advocacy and public policy reform. At the beginning of this year The G7 Kidnapped to Japan Reunification Project formed as an international alliance of partners who are parents and organizations from several countries including Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The objective is to bring about a rapid resolution to this crisis affecting the human rights of thousands of children abducted to or within Japan. Many Japanese citizens and officials have shared with me that they are deeply ashamed of these abductions and need help from the U.S. -

Garveyism: a ’90S Perspective Francis E

New Directions Volume 18 | Issue 2 Article 7 4-1-1991 Garveyism: A ’90s Perspective Francis E. Dorsey Follow this and additional works at: http://dh.howard.edu/newdirections Recommended Citation Dorsey, Francis E. (1991) "Garveyism: A ’90s Perspective," New Directions: Vol. 18: Iss. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://dh.howard.edu/newdirections/vol18/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Directions by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GARVEYISM A ’90s Perspective By Francis E. Dorsey Pan African Congress in Manchester, orn on August 17, 1887 in England in 1945 in which the delegates Jamaica, Marcus Mosiah sought the right of all peoples to govern Garvey is universally recog themselves and freedom from imperialist nized as the father of Pan control whether political or economic. African Nationalism. After Garveyism has taught that political power observing first-hand the in without economic power is worthless. Bhumane suffering of his fellow Jamaicans at home and abroad, he embarked on a mis The UNIA sion of racial redemption. One of his The corner-stone of Garvey’s philosophical greatest assets was his ability to transcend values was the establishment of the Univer myopic nationalism. His “ Back to Africa” sal Negro Improvement Association, vision and his ‘ ‘Africa for the Africans at UNIA, in 1914, not only for the promulga home and abroad” geo-political perspec tion of economic independence of African tives, although well before their time, are peoples but also as an institution and all accepted and implemented today. -

The Race Problem in Economics.Pdf

1/23/2020 The race problem in economics Up Front The race problem in economics Randall Akee Wednesday, January 22, 2020 n January 3, 2020 at the Allied Social Science Association (ASSA) annual meetings in San Diego, California—the largest annual gathering of economists— O I participated in a panel hosted by the American Economics Association (AEA) titled, “How Can Economics Solve Its Race Problem?” The panel was convened by Janet Yellen, Former Federal Reserve Board Chair, current AEA President, and Distinguished Fellow in Residence at Brookings, and moderated by Ebonya Washington, the Samuel C. Park Jr. Professor of Economics at Yale University. Fellow panelists included Drs. Trevon Logan, Marie Mora, Ted Miguel and Cecilia Conrad. This was the rst time in many years that such a panel was held at the ASSA meetings. Nevertheless, this has been an important topic of concern for many in the profession for decades. For instance, this year marks the 50th anniversary of the National Economics Association (NEA), which grew out of the Caucus of Black Economists and was established, in part, to “promote the professional lives of minorities within the profession.” The NEA has inspired the founding and creation of additional organizations with related missions, such as the American Society of Hispanic Economists (ASHE), founded in 2002, and the Association for Economic Research of Indigenous Peoples (AERIP), founded just last year and for which I serve as the president-elect. The economics profession is less diverse than the general population by race and gender. The lack of diversity has received increased attention in recent years due to incidents that have come to light about harassment and discrimination in the profession for women and minorities both online and in employment situations. -

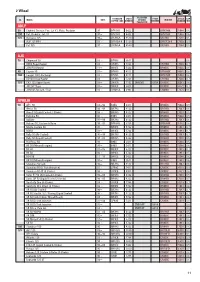

Fitment Chart (Pdf)

2 Wheel PLATINUM CC MODEL DATE STANDARD STOCK OR GOLD STOCK IRIDIUM STOCK GAP COPPER CORE NUMBER PALLADIUM NUMBER NUMBER MM ADLY 50 Citybird, Crosser, Fox, Jet X1, Pista, Predator 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 100 Cat, Predator, Jet, X1 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 125 Activator 125 99 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJP 125 PR4 03 DPR7EA-9 5129 DPR7EIX-9 7803 0.9 Cat 125 97 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJS 50 Chipmunk 50 03 BP4HS 3611 0.6 DD50 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 JSM 50 Motard 11 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 80 Coyote 80 03 BP6HS 4511 BPR6HIX 4085 0.6 100 Cougar 100 (Jincheng) 03 BP7HS 5111 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 DD100 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 125 CR3-125 Super Sports 08 DR8EA 7162 DR8EVX 6354 DR8EIX 6681 0.6 JS125Y Tiger 03 DR8ES 5423 DR9EIX 4772 0.7 JSM125 Motard / Trail 10 CR6HSA 2983 CR6HIX 7274 0.6 APRILIA 50 AF1 50 8892 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Amico 50 9294 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Area 51 (Liquid Cooled 2-Stroke) 98 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Extrema 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Gulliver 9799 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Habana 50, Custom & Retro 9905 BPR8HS 3725 BPR8HIX 6742 0.6 Mojito Custom 50 05 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 MX50 03 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 Rally 50 (Air Cooled) 9599 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.7 Rally 50 (Liquid Cooled) 9703 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Red Rose 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 RS 50 (Minarelli engine) 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 RS 50 0105 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 RS 50 06 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.5 RS4 50 1113 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 ‡ Early Ducati Testastretta bikes (749, 998, 999 models) can have very little clearance between the plug hex and the RX 50 (Minarelli engine) 97 B9ES 2611 BR9EIX 3981 0.6 cylinder head that may require a thin walled socket, no larger than 20.5mm OD to allow the plug to be fitted. -

Views That Barnes Has Given, Wherein

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Darker Matters: Racial Theorizing through Alternate History, Transhistorical Black Bodies, and Towards a Literature of Black Mecha in the Science Fiction Novels of Steven Barnes Alexander Dumas J. Brickler IV Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DARKER MATTERS: RACIAL THEORIZING THROUGH ALTERNATE HISTORY, TRANSHISTORICAL BLACK BODIES, AND TOWARDS A LITERATURE OF BLACK MECHA IN THE SCIENCE FICTION NOVELS OF STEVEN BARNES By ALEXANDER DUMAS J. BRICKLER IV A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Alexander Dumas J. Brickler IV defended this dissertation on April 16, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jerrilyn McGregory Professor Directing Dissertation Delia Poey University Representative Maxine Montgomery Committee Member Candace Ward Committee Member Dennis Moore Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Foremost, I have to give thanks to the Most High. My odyssey through graduate school was indeed a long night of the soul, and without mustard-seed/mountain-moving faith, this journey would have been stymied a long time before now. Profound thanks to my utterly phenomenal dissertation committee as well, and my chair, Dr. Jerrilyn McGregory, especially. From the moment I first perused the syllabus of her class on folkloric and speculative traditions of Black authors, I knew I was going to have a fantastic experience working with her. -

Black Capitalism’

Opinion The Real Roots of ‘Black Capitalism’ Nixon’s solution for racial ghettos was tax breaks and incentives, not economic justice. By Mehrsa Baradaran March 31, 2019 The tax bill President Trump signed into law in 2017 created an “opportunity zones” program, the details of which will soon be finalized. The program will provide tax cuts to investors to spur development in “economically distressed” areas. Republicans and Democrats stretching back to the Nixon administration have tried ideas like this and failed. These failures are well known, but few know the cynical and racist origins of these programs. The neighborhoods labeled “opportunity zones” are “distressed” because of forced racial segregation backed by federal law — redlining, racial covenants, racist zoning policies and when necessary, bombs and mob violence. These areas were black ghettos. So how did they come to be called “opportunity zones?” The answer lies in “black capitalism,” a forgotten aspect of Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy. Mr. Nixon's solution for racial ghettos was not economic justice, but tax breaks and incentives. This deft political move allowed him to secure the support of 2 white Southerners and to oppose meaningful economic reforms proposed by black activists. You can see how clever that political diversion was by looking at the reforms that were not carried out. After the Civil Rights Act, black activists and their allies pushed the federal government for race-specific economic redress. The “whites only” signs were gone, but joblessness, dilapidated housing and intractable poverty remained. In 1967, blacks had one-fifth the wealth of white families. ADVERTISEMENT Yet a white majority opposed demands for reparations, integration and even equal resources for schools. -

Volunteer Handbook

VOLUNTEER MANUAL http://wku.edu/hardinplanetarium 270 – 745 – 4044 Volunteer Positions [email protected] [email protected] Audience Assistant 6 [email protected] mailing address: Tech Operator 10 1906 College Heights Blvd. Suspendisse aliquam mi Bowling Green, KY 42101-1077 placerat sem. Vestibulum mapping address: idProduction lorem commodo Assistant justo 12 1501 State Street, Bowling Green, KY euismod tristique. Suspendisse arcu libero, Mission: euismodPresenter sed, tempor id, 12 Hardin Planetarium’s mission is to inspire lifelong facilisis non, purus. learning through interactive experiences that are both Aenean ligula. inspiring and factually accurate. Our audiences will be Behind the Scenes 12 encouraged to engage with exhibits and live presentations that further the public understanding and enjoyment of science. Every member or our audience deserves to be treated with respect. We do everything possible to create Appendices an atmosphere where each person can enjoy her/himself and learn as much as possible. Set up / shut down 13 History: An iconic architectural landmark at Western Kentucky University, Hardin Planetarium was dedicated in October Star Stories set up 15 1967. The dome shaped building is 72-feet in diameter and 44 feet high. The interior includes two levels encompassing 6,000 square feet. The star chamber seats Emergency Procedures 16 over 100 spectators on upholstered benches arranged concentrically around the central projector system. Digitarium 16 The planetarium is named for Hardin Cherry Thompson quick-start guide [1938-1963], son of WKU president Kelly Thompson, who died during his senior year at the University. In 2012, audiences at Hardin Planetarium first enjoyed the power Volunteer Agreement 17 of full dome digital simulations, when the projection system was re-outfitted with a Digitalis Epsilon digital projector.