Bob Kaufman, the Popular Front, and the Black Arts Movement J Smethurst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

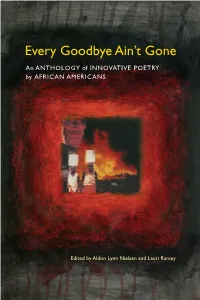

Every Goodbye Ain't Gone

Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An ANTHOLOGY of INNOVATIVE POETRY by AFRICAN AMERICANS Edited by Aldon Lynn Nielsen and Lauri Ramey Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY POETICS Series Editors Charles Bernstein Hank Lazer Series Advisory Board Maria Damon Rachel Blau DuPlessis Alan Golding Susan Howe Nathaniel Mackey Jerome McGann Harryette Mullen Aldon Nielsen Marjorie Perloff Joan Retallack Ron Silliman Lorenzo Thomas Jerr y Ward You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An Anthology of Innovative Poetry by African Americans Edited by ALDON LYNN NIELSEN and LAURI RAMEY THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA PRESS Tuscaloosa You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Copyright © 2006 The University of Alabama Press Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0380 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Typeface: Janson Text ∞ The paper on which this book is printed meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

158 Kansas History the Hard Kind of Courage: Labor and Art in Selected Works by Langston Hughes, Gordon Parks, and Frank Marshall Davis

Gordon Parks’s American Gothic, Washington, D.C., which captures government charwoman Ella Watson at work in August 1942. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 36 (Autumn 2013): 158–71 158 Kansas History The Hard Kind of Courage: Labor and Art in Selected Works by Langston Hughes, Gordon Parks, and Frank Marshall Davis by John Edgar Tidwell hen and in what sense can art be said to require a “hard kind of courage”? At Wichita State University’s Ulrich Museum, from September 16 to December 16, 2012, these questions were addressed in an exhibition of work celebrating the centenary of Gordon Parks’s 1912 birth. Titled “The Hard Kind of Courage: Gordon Parks and the Photography of the Civil Rights Era,” this series of deeply profound images offered visual testimony to the heart-rending but courageous sacrifices made by Freedom Riders, the bombing victims Wat the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, the energized protesters at the Great March on Washington, and other participants in the movement. “Photographers of the era,” the exhibition demonstrated, “were integral to advancing the movement by documenting the public and private acts of racial discrimination.”1 Their images succeeded in capturing the strength, fortitude, resiliency, determination, and, most of all, the love of those who dared to step out on faith and stare down physical abuse and death. It is no small thing that all this was done amidst the challenges of being a black artist or writer seeking self-actualization in a racially charged era. -

A Guide for Teaching the Contributions of the Negro Author to American Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 043 635 TE 002 075 AUTHOR Simon, Eugene r. TITLE A Guide for Teaching the Contributions of the Negro Author to American Literature. INSTITUTION San Diego City Schools, Calif. PUB DATE 68 NOTE uln. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 BC-$2.1 DESCRIPTORS *African American Studies, *American Literature, Authors, Autobiographies, Piographies, *Curriculum Guides, Drama, Essays, Grade 11, Music, Negro Culture, Negro History, *Negro Literature, Novels, Poetry, Short Stories ABSTRACT This curriculum guide for grade 11 was written to provide direction for teachers in helping students understand how Negro literature reflects its historical background, in integrating Black literature into the English curriculum, in teaching students literary structure, and in comparing and contrasting Negro themes with othr themes in American literature. Brief outlines are provided for four literary periods; (1) the cry for freedom (1619-186c), (2) the period of controversy and search for identity (18(5-1015), (1) the Negro Renaissance (191-1940), and (4) the struggle for equality (101-1968). '*he section covering the Negro Renaissance provides a discussiol of the contributions made during that Period in the fields of the short sto:y, the essay, the novel, poetry, drama, biography, and autobiography.A selected bibliography of Negro literalAre includes works in all these genres as well as works on American Negro music. (D!)) U.S. DIPAIIMINI Of KEITH, MOTION t WItfANI Ulla Of EDUCATION L11 rIN iMIS DOCUMENT HAS SUN IMPRODIXID HAIR IS WINED FROM EIIE PINSON Of ONINI/AliON 011411111110 ElPOINTS Of VIEW Of OPINIONS tes. MUD DO NOT NICISSAINY OMEN! Offg lit OHM Of EDIKIIION POSITION 01 PEW. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

1-54 FORUM Talks Programme Announced for Second Edition in Marrakech, Curated by Art Historian and Curator Karima Boudou

1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair La Mamounia, Marrakech, 23 – 24 February 2019 1-54 FORUM talks programme announced for second edition in Marrakech, curated by art historian and curator Karima Boudou • Twelfth edition of 1-54 FORUM, titled ‘Let’s Play Something Let’s Play Anything Let’s Play’1, will examine narratives of surrealism in Africa and its diaspora • Conversation on Ted Joans’ relationship with surrealism by lecturer Joanna Pawlik • Screenings of work by filmmakers Kara Walker and Louis Van Gasteren • Panel discussions on the contemporary use of sound and language to liberate the unconscious and document it • Talk on Maghrebian Surrealism and the Surrealist movement in Egypt L-R: Noureddine Ezarraf, The Public Writer, 2017, installation. Photo by Lisa Stewart of Queens Collective. Courtesy the artist; Vince Fraser, BLAQUE MATISSE, 2017. Courtesy the artist; Abdellah Hassak, Alarme! Alarme! Alarme!, 2016. Courtesy the artist. 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, the leading international art fair dedicated to contemporary African art, has announced details of 1-54 FORUM, the fair’s acclaimed talks and events programme, for the second Marrakech edition in February. Curated for the first time by art historian and curator, Karima Boudou, the programme entitled ‘Let’s Play Something Let’s Play Anything Let’s Play’ will take place during the fair at La Mamounia. In addition, 1-54 FORUM will host three sessions around the city at ESAV (L'École Supérieure des Arts Visuels de Marrakech), Musée Yves Saint Laurent Marrakech and Le 18, a multidisciplinary art space. 1-54 Marrakech 2019 will present 18 leading galleries from 11 countries featuring more than 65 artists from Africa and its diaspora. -

Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014 Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rutter, E. (2014). Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1136 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Copyright by Emily Ruth Rutter 2014 ii CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter Approved March 12, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda A. Kinnahan Kathy L. Glass Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Laura Engel Thomas P. Kinnahan Associate Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal Greg Barnhisel Dean, McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Chair, English Department Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of English iii ABSTRACT CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda A. -

CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty

APPARATUS POETICA: THE QUESTION OF TECHNOLOGY IN MID-TWENTIETH- CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Avery Slater August 2014 © 2014 Avery Slater APPARATUS POETICA: THE QUESTION OF TECHNOLOGY IN MID-TWENTIETH- CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY Avery Slater, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 “Apparatus Poetica” considers how four poets in the late modernist tradition reconceive the potentials of poetic language in order to address the question of advanced technology. Outlining challenges posed to language by communications industries, information theory, computation, and the threat of nuclear war, I show how four poets—James Merrill, Muriel Rukeyser, H.D., and Jack Spicer—explore affinities and crucial distinctions between poetry and technology. Through their experiments in what I call “apparatus poetics,” these poets denaturalize culturally embedded assumptions surrounding technology’s “neutrality” and poetry’s expressive “purity.” They do so through procedural innovations in the genre of the poetic epic, that form not coincidentally deemed by modernist anthropologists as the earliest human memory-technology. I begin with a discussion of how the montage apparatus of testimonial poetry in Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead works to indict industrial capital’s technological tactics of historical effacement. I next discuss how Jack Spicer, working as a structural linguist in the age of IBM, uses a late modernist method, the “serial lyric,” to set up a confrontation between poetic consciousness and language. Spicer casts the old predicament of thought’s alienation from language in a new light defined by contemporary forms of technological emergence (especially computational intelligence). -

Small Magazines

The ENGLISH JOURNAL Vol. XIX NOVEMBER 1930 No. 9 SMALL MAGAZINES EZRA POUND I The earlier history—I might almost call it the pre-history of the small magazines in America—has been ably and conscientiously presented by Dr. Rene Taupin in his L'lnfluence du Symbolisme Francais sur la Poesie Americaine (Paris: Champion, 1930); and I may there leave it for specialists. The active phase of the small magazine in America begins with the founding of Miss Monroe's magazine, Poetry, in Chicago in 1911. The significance of the small magazine has, obviously, noth ing to do with format. The significance of any work of art or litera ture is a root significance that goes down into its original motivation. When this motivation is merely a desire for money or publicity, or when this motivation is in great part such a desire for money direct ly or for publicity as a means indirectly of getting money, there oc curs a pervasive monotony in the product corresponding to the un derlying monotony in the motivation. The public runs hither and thither with transitory pleasures and underlying dissatisfactions; the specialists say: "This isn't litera ture." And a deal of vain discussion ensues. The monotony in the product arises from the monotony in the motivation. During the ten or twenty years preceding 1912 the then-called "better magazines" had failed lamentably and even offensively to maintain intellectual life. They are supposed to have been "good" 689 690 THE ENGLISH JOURNAL during some anterior period. Henry Adams and Henry James were not, at the starts of their respective careers, excluded; but when we reach our own day, we find that Adams and James had a contempt for American editorial opinion in no way less scalding than—let us say—Mr. -

Manhattan, Kansas African American History Trail Self-Guided Driving

1 Manhattan, Kansas African American History Trail Self-Guided Driving Tour July 2020 This self-guided driving tour was developed by the staff of the Riley County Historical Museum to showcase some of the interesting and important African American history in our community. You may start the tour at the Riley County Historical Museum, or at any point along to tour. Please note that most sites on the driving tour are private property. Sites open to the public are marked with *. If you have comments or corrections, please contact the Riley County Historical Museum, 2309 Claflin Road, Manhattan, Kansas 66502 785-565-6490. For additional information on African Americans in Riley County and Manhattan see “140 Years of Soul: A History of African-Americans in Manhattan Kansas 1865- 2005” by Geraldine Baker Walton and “The Exodusters of 1879 and Other Black Pioneers of Riley County, Kansas” by Marcia Schuley and Margaret Parker. 1. 2309 Claflin Road *Riley County Historical Museum and the Hartford House, open Tuesday through Friday 8:30 to 5:00 and Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00. Admission is free. The Museum features changing exhibits on the history of Riley County and a research archive/library open by appointment. The Hartford House, one of the pre-fabricated houses brought on the steamboat Hartford in 1855, is beside the Riley County Historical Museum. 2. 2301 Claflin Road *Goodnow House State Historic Site, beside the Riley County Historical Museum, is open Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00 and when the Riley County Historical Museum is open and staff is available. -

The Vlakh-Bor™,^ • University of Hawaii

THE VLAKH-BOR™,^ • UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII-. n ■ ■ LIBRARY -' - .. ........__________________ Page Five HONO., T.H.52 8-4-49 ~ Sec. 562, P. L. & R. .U. S. POSTAGE Single Issue 1* PAID The Newspaper Hawaii Needs Honolulu, T. H. 10c $5.00 per year Permit No. 189 by subscription Vol. 1, No. 40 PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY May SMW Advertiser Does It Again! TH LABOR LOSES $100,000 BY LEGISLATIVE SLOTH "Red” Smew Is DamonDemos Solons Improve 29 Yews Old Protest Big WCL; Provide No Hike In 1 axes Staff Addition By STAFF WRITER Land that formerly cost own Working-people in Hawaii will ers in Damon Tract taxes of three be deprived of $100,000 rightfully cents per square foot has this year due them next • year, because the been assessed at 10 cents per square legislature failed to implement the foot, and as a result, a number improved Workmen’s Compensa of Damon Tract people are indig tionLaw by providing a staff ca- . nantly and actively protesting. pable of administering it. That , “The .increase,” says Henry Ko-. is the opinion of William- M. -Doug kona, Damon Tract resident who las of the Bureau of Workmen’s leads the movement, “is from 100 Compensation. v. ■ . to 400 per cent, varying with the The platforms of both parties number of improvements on the included statements approving ad place. The assessor says it’s be- ditions to the Bureau’s.very small . cause Damon Tract has become staff, no additions >were made, a - residential district. Before, it though some very substantial im was assessed as farming land.-” provements .were realized.