CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetics of Landscape in Gary Snyder and Jack Spicer's

ELLit : 2nd Online National Seminar on English Linguistics and Literature July, 16 2020 POETICS OF LANDSCAPE IN GARY SNYDER AND JACK SPICER’S POEMS: EVOKING ONE’S SENSE OF TIME AND PLACE IN A POST-TRUTH ERA OF ANTHROPOCENE Henrikus Joko Yulianto Universitas Negeri Semarang [email protected] Abstract Poetry should not only be dulce but also utile or being sweet and useful as what a Latin poet Horatius once said. The essence of usefulness is very indispensable in this recent post-truth era when the surging digital technology has contributed to the an escalating anthropocentric culture. Consumerism and other anthropogenic activities that pervade human daily life are the very epitome of this anthropocentrism. An obvious impact but also a polemical controversy of these practices is global warming as one ecological phenomenon. Ecopoetry as a sub-genre of environmental humanities or ecocriticism aims to unveil the truth that the biotic community consists of the interdependent relation between human and nonhuman animals and their physical environment. This ecological fact is an indisputable truth that differs from the one of social or political facts. Gary Snyder and Jack Spicer as two poets of the San Francisco Renaissance movement in the 1950s are two figures who show concern about human interconnection with material phenomena. In their succinct poems, they open one’s awareness that any material good is not an object but that each material thing co-exists with one’s consciousness in certain time and place. Their landscape poetics then is able to evoke one’s understanding of his/her interconnection with any life form in the natural world. -

Addison Street Poetry Walk

THE ADDISON STREET ANTHOLOGY BERKELEY'S POETRY WALK EDITED BY ROBERT HASS AND JESSICA FISHER HEYDAY BOOKS BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA CONTENTS Acknowledgments xi Introduction I NORTH SIDE of ADDISON STREET, from SHATTUCK to MILVIA Untitled, Ohlone song 18 Untitled, Yana song 20 Untitied, anonymous Chinese immigrant 22 Copa de oro (The California Poppy), Ina Coolbrith 24 Triolet, Jack London 26 The Black Vulture, George Sterling 28 Carmel Point, Robinson Jeffers 30 Lovers, Witter Bynner 32 Drinking Alone with the Moon, Li Po, translated by Witter Bynner and Kiang Kang-hu 34 Time Out, Genevieve Taggard 36 Moment, Hildegarde Flanner 38 Andree Rexroth, Kenneth Rexroth 40 Summer, the Sacramento, Muriel Rukeyser 42 Reason, Josephine Miles 44 There Are Many Pathways to the Garden, Philip Lamantia 46 Winter Ploughing, William Everson 48 The Structure of Rime II, Robert Duncan 50 A Textbook of Poetry, 21, Jack Spicer 52 Cups #5, Robin Blaser 54 Pre-Teen Trot, Helen Adam , 56 A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley, Allen Ginsberg 58 The Plum Blossom Poem, Gary Snyder 60 Song, Michael McClure 62 Parachutes, My Love, Could Carry Us Higher, Barbara Guest 64 from Cold Mountain Poems, Han Shan, translated by Gary Snyder 66 Untitled, Larry Eigner 68 from Notebook, Denise Levertov 70 Untitied, Osip Mandelstam, translated by Robert Tracy 72 Dying In, Peter Dale Scott 74 The Night Piece, Thorn Gunn 76 from The Tempest, William Shakespeare 78 Prologue to Epicoene, Ben Jonson 80 from Our Town, Thornton Wilder 82 Epilogue to The Good Woman of Szechwan, Bertolt Brecht, translated by Eric Bentley 84 from For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide I When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Ntozake Shange 86 from Hydriotaphia, Tony Kushner 88 Spring Harvest of Snow Peas, Maxine Hong Kingston 90 Untitled, Sappho, translated by Jim Powell 92 The Child on the Shore, Ursula K. -

Radio Transmission Electricity and Surrealist Art in 1950S and '60S San

Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 9:1 (2016), 40-61 40 Radio Transmission Electricity and Surrealist Art in 1950s and ‘60s San Francisco R. Bruce Elder Ryerson University Among the most erudite of the San Francisco Renaissance writers was the poet and Zen Buddhist priest Philip Whalen (1923–2002). In “‘Goldberry is Waiting’; Or, P.W., His Magic Education As A Poet,” Whalen remarks, I saw that poetry didn’t belong to me, it wasn’t my province; it was older and larger and more powerful than I, and it would exist beyond my life-span. And it was, in turn, only one of the means of communicating with those worlds of imagination and vision and magical and religious knowledge which all painters and musicians and inventors and saints and shamans and lunatics and yogis and dope fiends and novelists heard and saw and ‘tuned in’ on. Poetry was not a communication from ME to ALL THOSE OTHERS, but from the invisible magical worlds to me . everybody else, ALL THOSE OTHERS.1 The manner of writing is familiar: it is peculiar to the San Francisco Renaissance, but the ideas expounded are common enough: that art mediates between a higher realm of pure spirituality and consensus reality is a hallmark of theopoetics of any stripe. Likewise, Whalen’s claim that art conveys a magical and religious experience that “all painters and musicians and inventors and saints and shamans and lunatics and yogis and dope fiends and novelists . ‘turned in’ on” is characteristic of the San Francisco Renaissance in its rhetorical manner, but in its substance the assertion could have been made by vanguard artists of diverse allegiances (a fact that suggests much about the prevalence of theopoetics in oppositional poetics). -

Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, Bulk 1943-1965

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9199r33h No online items Finding Aid to the Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, bulk 1943-1965 Finding Aid written by Kevin Killian The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Jack Spicer BANC MSS 2004/209 1 Papers, 1939-1982, bulk 1943-1965 Finding Aid to the Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, bulk 1943-1965 Collection Number: BANC MSS 2004/209 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Kevin Killian Date Completed: February 2007 © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Jack Spicer papers Date (inclusive): 1939-1982, Date (bulk): bulk 1943-1965 Collection Number: BANC MSS 2004/209 Creator : Spicer, Jack Extent: Number of containers: 32 boxes, 1 oversize boxLinear feet: 12.8 linear ft. Repository: The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Abstract: The Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, document Spicer's career as a poet in the San Francisco Bay Area. Included are writings, correspondence, teaching materials, school work, personal papers, and materials relating to the literary magazine J. Spicer's creative works constitute the bulk of the collection and include poetry, plays, essays, short stories, and a novel. Correspondence is also significant, and includes both outgoing and incoming letters to writers such as Robin Blaser, Harold and Dora Dull, Robert Duncan, Lewis Ellingham, Landis Everson, Fran Herndon, Graham Mackintosh, and John Allan Ryan, among others. -

{PDF EPUB} the Sky Changes by Gilbert Sorrentino Gilbert Sorrentino

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Sky Changes by Gilbert Sorrentino Gilbert Sorrentino. Gilbert Sorrentino (born April 27, 1929 in Brooklyn , New York City , † May 18, 2006 in New York City) was an American writer. In 1956 Sorrentino and his friends from Brooklyn College, including childhood friend Hubert Selby Jr., founded the literary magazine Neon , which was published until 1960. After that he was one of the editors of Kulchur magazine . After working closely with Selby on the manuscript of Last Exit to Brooklyn in 1964, he became an editor at underground publisher Grove Press (from 1965 to 1970). He supervised u. a. The Autobiography of Malcolm X . Sorrentino was Professor of English at Stanford University from 1982 to 1999 . Among his students were the writers Jeffrey Eugenides and Nicole Krauss. His son Christopher Sorrentino is the novelist of Sound on Sound and Trance. Sorrentino's first novel, The Sky Changes , was published in 1966 . Other important novels were Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things , Blue Pastoral and Mulligan Stew. Sorrentino is one of the better known authors of the literary postmodern . His novels Mulligan Stew and The Apparent Deflection of Starlight , also translated into German, have a metafictional character. Gilbert Sorrentino. The maverick American novelist and poet Gilbert Sorrentino, who has died aged 77, is best known for Mulligan Stew (1979), a novel drawing upon characters from Dashiell Hammett, F Scott Fitzgerald and Flann O'Brien, and one from a James Joyce footnote. The labyrinthine ways of this freewheeling escapade make it no surprise that Sorrentino's favourite novel was Tristram Shandy. -

Born in Oklahoma in 1929, of Native American Origin, Fran Herndon Escaped to Europe Just As Senator Joseph Mccarthy Turned This Country Upside Down

KEVIN KILLIAN / Fran Herndon1 Born in Oklahoma in 1929, of Native American origin, Fran Herndon escaped to Europe just as Senator Joseph McCarthy turned this country upside down. The U.S., she told us recently, was then "no place for a brown face." In France she met and married the teacher and writer James Herndon, and the couple moved to San Francisco in 1957. (The first of their two sons, Jay, was born the same year.) Shortly after arriving in the Bay Area she met four old friends of her husband's: Jack Spicer, Robin Blaser, Robert Duncan and Jess-the brilliant crew that had invented the Berkeley Renaissance ten years earlier, artists now all working at the height of their poetic powers in a highly charged urban bohemia. Fran Herndon became most deeply involved with the most irascible of them all. From the very first evening that they had spent time together, Jack Spicer (1925-1965) seemed to see something unusual, something vivid in Fran that she had not seen herself. It was as if he were establishing a person, the way he created a poem, out of the raw materials she presented, and for a long time she did not know what it was he wanted her to be. Fran was mystified but elated by a power that Jack saw hidden inside her demure, polite social persona. He knew before she did that she would never be completely satisfied with the roles of mother and housewife. When Spicer scrutinized her, as if envisioning in his mind's eye a new and somehow different person, she began thinking: there must be some off-moments from being a mother, and during those moments, what would she do? "I remember clearly discussing school with him. -

Published Occasionally by the Friends of the Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley, California 94720

PUBLISHED OCCASIONALLY BY THE FRIENDS OF THE BANCROFT LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94720 No. 6l May 197s Dr. and Mrs. David Prescott Barrows, with their children, Anna, Ella, Tom, and Betty, at Manila, ig And it is the story of "along the way" that '111 Along the Way comprises this substantial transcript, a gift from her children in honor of Mrs. Hagar's You Have Fun!" seventy-fifth birthday. In her perceptive introduction to Ella Bar From a childhood spent for the most part rows Hagar's Continuing Memoirs: Family, in the Philippines where her father, David Community, University, Marion Sproul Prescott Barrows, served as General Super Goodin notes that the last sentence of this intendent of Education, Ella Barrows came interview, recently completed by Bancroft's to Berkeley in 1910, attended McKinley Regional Oral History Office, ends with the School and Berkeley High School, and en phrase: "all along the way you have fun!" tered the University with its Class of 1919. [1] Life in the small college town in those halcy Annual Meeting: June 1st Bancroft's Contemporary on days before the first World War is vividly recalled, and contrasted with the changes The twenty-eighth Annual Meeting of Poetry Collection brought about by the war and by her father's The Friends of The Bancroft Library will be appointment to the presidency of the Uni held in Wheeler Auditorium on Sunday IN THE SUMMER OF 1965 the University of versity in December, 1919. From her job as afternoon, June 1st, at 2:30 p.m. -

The Superseding, a Prague Nocturne 141

| | | | The Return of Král Majáles PRAGUE’S INTERNATIONAL LITERARY RENAISSANCE 990-00 AN ANTHOLOGY | Edited by LOUIS ARMAND Copyright © Louis Armand, 2010 Copyright © of individual works remains with the authors Copyright © of images as captioned Published 1 May, 2010 by Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická Fakulta Litteraria Pragensia Books Centre for Critical & Cultural Theory, DALC Náměstí Jana Palacha 2 116 38 Praha 1, Czech Republic All rights reserved. This book is copyright under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the copyright holders. Requests to publish work from this book should be directed to the publish- ers. ‘Cirkus’ © 2010 by Myla Goldberg. Used by permission of Wendy Schmalz Agency. The publication of this book has been partly supported by research grant MSM0021620824 “Foundations of the Modern World as Reflected in Literature and Philosophy” awarded to the Faculty of Philosophy, Charles University, Prague, by the Czech Ministry of Education. All reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders. | Cataloguing in Publication Data The Return of Král Majáles. Prague’s International Literary Renaissance 1990-2010 An Anthol- ogy, edited by Louis Armand.—1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 978-80-7308-302-1 (pb) 1. Literature. 2. Prague. 3. Central Europe. I. Armand, Louis. II. Title Printed in the Czech Republic by PB Tisk Cover, typeset & design © lazarus Cover image: Allen Ginsberg in Prague, 1965. Photo: ČTK. Inside pages: 1. Allen Ginsberg in Prague, 1965. Photo: ČTK. -

Red Or Dead: States of Poetry in Depression America

Red or Dead: States of Poetry in Depression America by Sarah Elizabeth Ehlers A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Alan M. Wald, Chair Professor Howard Brick Professor June M. Howard Professor Yopie Prins Associate Professor Joshua L. Miller ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The same year I began my Ph.D. work at the University of Michigan, my father lost the coal-mining job he had worked for over twenty years. That particular confluence of events had a profound effect on me, and I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the ways in which my personal feelings of anger and frustration—my sense of being somehow out-of-place—influenced my thinking and this project. Certainly, it was one of the catalysts for my deep interest in the U.S. literary Left. Like so many others, I am indebted to Alan Wald for my understanding of Left literature and culture. Alan has been, probably more than he knows, an example of the kind of scholar I hope to be—even, I admit, an ideal ego of sorts. I continue to be as awed by his deep knowledge as I am by his humility and generosity. Yopie Prins taught me how to read poetry when I already thought I knew how, and my conversations with her over the past five years have shaped my thinking in remarkable ways. From my first days in Ann Arbor, June Howard has been a source of intellectual guidance, and her insights on my work and the profession have been a sustaining influence. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-04036-6 - The Cambridge Companion to Modern American Poetry Edited by Walter Kalaidjian Excerpt More information WALTER KALAIDJIAN Introduction Increasingly, contemporary critical accounts of what William Carlos Williams called “the local conditions” ( 1948 , 146) of modern American poetry have engaged more worldly expanses of time and space, reading American verse written over the past century in the contexts of United States history and culture that participate in a decidedly global community. This collection in particular stretches the more narrow period term of literary modernism – works published between, say, 1890 and 1945 – favoring a more capacious and usable account of poetry’s “modern” evolution over the entire twenti- eth century up to the present . Supplementing the protocols of literary “close reading” advanced by the so-called American New Critics, studies of mod- ern American poetry have moved beyond attention to the isolated work of literature, the focus on a single author, and the domestic containments of national narration . Not unlike Ezra Pound’s 1934 description of the American epic as a “poem containing history,” contemporary criticism of American verse has sought to contextualize canonical and emerging poems against wider political, social, and cultural fi elds and forces. These and other advances in the reception of modern American poetry refl ect broader and concerted efforts to question, revise, and expand the received canon of American literature. Such revisionary initiatives date back to the latter decades of the twentieth century with Paul Lauter’s “Reconstructing American Literature” project. It began as a series of conferences sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation and Lilly Endowment, later published in the critical volume Reconstructing American Literature (1983) followed by Sacvan Bercovitch’s scholarly col- lection Reconstructing American Literary History (1986). -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC ARCHIVES & COLLECTIONS / RECENT ACQUISITIONS 15 Academy Street P. O. Box 668 Salisbury, CT 06068 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. [ANTHOLOGY] CUNARD, Nancy, compiler & contributor. Negro Anthology. 4to, illustrations, fold-out map, original brown linen over beveled boards, lettered and stamped in red, top edge stained brown. London: Published by Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co, 1934. First edition, first issue binding, of this landmark anthology. Nancy Cunard, an independently wealthy English heiress, edited Negro Anthology with her African-American lover, Henry Crowder, to whom she dedicated the anthology, and published it at her own expense in an edition of 1000 copies. Cunard’s seminal compendium of prose, poetry, and musical scores chiefly reflecting the black experience in the United States was a socially and politically radical expression of Cunard’s passionate activism, her devotion to civil rights and her vehement anti-fascism, which, not surprisingly given the times in which she lived, contributed to a communist bias that troubles some critics of Cunard and her anthology. Cunard’s account of the trial of the Scottsboro Boys, published in 1932, provoked racist hate mail, some of which she published in the anthology. Among the 150 writers who contributed approximately 250 articles are W. E. B. Du Bois, Arna Bontemps, Sterling Brown, Countee Cullen, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Samuel Beckett, who translated a number of essays by French writers; Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, George Antheil, Ezra Pound, Theodore Dreiser, among many others. -

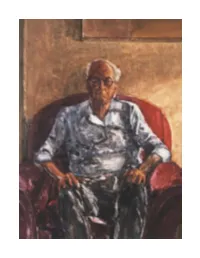

William Bronk

Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk David Clippinger Argotist Ebooks 2 * Cover image by Daniel Leary Copyright © David Clippinger 2012 All rights reserved Argotist Ebooks * Bill in a Red Chair, monotype, 20” x 16” © Daniel Leary 1997 3 The surest, and often the only, way by which a crowd can preserve itself lies in the existence of a second crowd to which it is related. Whether the two crowds confront each other as rivals in a game, or as a serious threat to each other, the sight, or simply the powerful image of the second crowd, prevents the disintegration of the first. As long as all eyes are turned in the direction of the eyes opposite, knee will stand locked by knee; as long as all ears are listening for the expected shout from the other side, arms will move to a common rhythm. (Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power) 4 Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk 5 Part I “So Large in His Singleness” By 1960 William Bronk had published a collection, Light and Dark (1956), and his poems had appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, Origin, and Black Mountain Review. More, Bronk had earned the admiration of George Oppen and Charles Olson, as well as Cid Corman, editor of Origin, James Weil, editor of Elizabeth Press, and Robert Creeley. But given the rendering of the late 1950s and early 1960s poetry scene as crystallized by literary history, Bronk seems to be wholly absent—a veritable lacuna in the annals of poetry.