An Artback NT Education Resource ITINERARY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Google Chrome Scores at SXSW Interactive Awards 16 March 2011, by Glenn Chapman

Google Chrome scores at SXSW Interactive awards 16 March 2011, by Glenn Chapman type of video," Google's Thomas Gayno told AFP after the award ceremony. "For Google it is very compelling because it allows us to push the browser to its limits and move the Web forward." Visitors to the website enter addresses where they lived while growing up to be taken on nostalgic trips by weaving Google Maps and Street View images with the song "We Used to Wait." A woman works on her computer as on the wall behind "It takes you on a wonderful journey all is seen the logo of Google in Germany 2005. A music synchronized with music," Gayno said. "It is like and imagery website that shows off capabilities of choreography of browser windows." Google's Chrome Web browser won top honors at a South By Southwest Interactive (SXSW) festival known US Internet coupon deals website Groupon was for its technology trendsetters. voted winner of a People's Choice award in keeping with a trend of SXSW goers using smartphones to connect with friends, deals, and happenings in the real world. A music and imagery website that shows off capabilities of Google's Chrome Web browser won Founded in 2008, Chicago-based Groupon offers top honors at a South By Southwest Interactive discounts to its members on retail goods and (SXSW) festival known for its technology services, offering one localized deal a day. trendsetters. A group text messaging service aptly named The Wilderness Downtown was declared Best of GroupMe was crowned the "Breakout Digital Trend" Show at an awards ceremony late Tuesday that at SXSW. -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

Sorry Day Is a Day Where We Remember the Stolen Generations

Aboriginal Heritage Office Yarnuping Education Series Ku-ring-gai, Lane Cove, North Sydney, Northern Beaches, Strathfield and Willoughby Councils © Copyright Aboriginal Heritage Office www.aboriginalheritage.org Yarnuping 5 Sorry Day 26th May 2020 Karen Smith Education Officer Sorry Day is a day where we remember the Stolen Generations. Protection & Assimilation Policies Have communities survived the removal of children? The systematic removal and cultural genocide of children has an intergenerational, devastating effect on families and communities. Even Aboriginal people put into the Reserves and Missions under the Protectionist Policies would hide their children in swamps or logs. Families and communities would colour their faces to make them darker. Not that long after the First Fleet arrived in 1788, a large community of mixed ancestry children could be found in Sydney. They were named ‘Friday’, ‘Johnny’, ‘Betty’, and denied by their white fathers. Below is a writing by David Collins who witnessed this occurring: “The venereal disease also has got among them, but I fear our people have to answer for that, for though I believe none of our women had connection with them, yet there is no doubt that several of the Black women had not scrupled to connect themselves with the white men. Of the certainty of this extraordinary instance occurred. A native woman had a child by one of our people. On its coming into the world she perceived a difference in its colour, for which not knowing how to account, she endeavoured to supply by art what she found deficient in nature, and actually held the poor babe, repeatedly over the smoke of her fire, and rubbed its little body with ashes and dirt, to restore it to the hue with which her other children has been born. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Anthropology of Indigenous Australia

Anthropology of Indigenous Australia Class code ANTH-UA 9037 – 001 Instructor Petronella Vaarzon-Morel Details [email protected] Consultations by appointment. Please allow at least 24 hours for your instructor to respond to your emails. Class Details Fall 2017 Anthropology of Indigenous Australia Tuesday 12:30 – 3:30pm 5 September to 12 December Room 202 NYU Sydney Academic Centre Science House: 157-161 Gloucester Street, The Rocks 2000 Prerequisites None. Class This course offers an introduction to some of the classical and current issues in the Description anthropology of Indigenous Australia. The role of anthropology in the representation and governance of Indigenous life is itself an important subject for anthropological inquiry, considering that Indigenous people of Australia have long been the objects of interest and imagination by outsiders for their cultural formulations of kinship, ritual, art, gender, and politics. These representations—in feature films about them (such as Rabbit-Proof Fence and Australia), New Age Literature (such as Mutant Message Down Under), or museum exhibitions (such as in the Museum of Sydney or the Australian Museum)—are now also in dialogue with Indigenous forms of cultural production, in genres as diverse as film, television, drama, dance, art and writing. The course will explore how Aboriginal people have struggled to reproduce themselves and their traditions on their own terms, asserting their right to forms of cultural autonomy and self-determination. Through the examination of ethnographic and historical texts, films, archives and Indigenous life-writing accounts, we will consider the ways in which Aboriginalities are being challenged and constructed in contemporary Australia. -

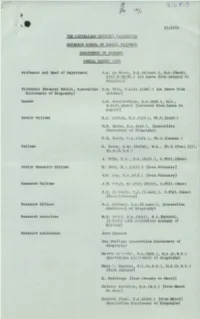

General Editor, Australian Dictionary of Biography

J_ \,. r-- 1 21/1970 RESF.ARCH SCHOOL OF SOCL\1....;s.,ru_~F.S DEPARTMENr OF li1§_TO~~ ANNUAL REPORT J.969 Professor and Head of Department J.A. La N2uz~, B.A.(W.Aust.), M.A.(Oxon), Litt.D. (M2lb.) [on leave from January to t~ov c r.:be r ] Professor (General Editor, Australian D. I-I. Pil:c, D. Litt. (Adel. ) [ on leave from Dictionary of Biography) October] Reader L.F. Fit~h3rdinge, B.A.(Syd.), M.A., B.Li t t .(Oxon) [returned from leave in Aug us t] Senior Fellows R.A. Golian, M. A. ( Syd.), Ph.D.(Lond.) N.B. Nairn, H.A. (Syd.), (Australian Dicti or.ary of Biography) F.B. S:nith, !1. A.(:1e lb.), Ph.D.(Cantab.) Fellows R. KtL.~r, B.Sc.(Delhi), M.A., Ph.D.(Panj.(I)), Ph .D. (A. :q.u,) J. E".!dy, S.J., B.A.(?'ielb.), D.Phil.(Oxon) Senior Research Fellows W. E:i t c , 11. A. {:::lb.) [from February] P.R. 1':'ly, i'1, A. ( n.z. ) [from February] Research Fellows J.H. \1-)igt, D:- . phil.(Ki e l), D.Phil,(Oxon) B. K. c~ Gnis, !1. A. (W,Aust.), D.Phil.(Oxon) [ frc:::i. ;;; ~bruary] Research Officer H.J. Gib~n~y, E.A.(W.Aust:), (Australian Dictfo:,.-1~-y of Diogrnphy) Research Associate M.E. I-:c ~c"l , B.A. (Hull), M.A.(Monash), ( j.:'.in ::::~.y ,;ith /,untralian Academy of Scbr..ce) Research Assistants Joa n Lynra·.m Nan Phillips (Australian Dictionary of Biography) Martha F..c'::!. -

Noun Phrase Constituency in Australian Languages: a Typological Study

Linguistic Typology 2016; 20(1): 25–80 Dana Louagie and Jean-Christophe Verstraete Noun phrase constituency in Australian languages: A typological study DOI 10.1515/lingty-2016-0002 Received July 14, 2015; revised December 17, 2015 Abstract: This article examines whether Australian languages generally lack clear noun phrase structures, as has sometimes been argued in the literature. We break up the notion of NP constituency into a set of concrete typological parameters, and analyse these across a sample of 100 languages, representing a significant portion of diversity on the Australian continent. We show that there is little evidence to support general ideas about the absence of NP structures, and we argue that it makes more sense to typologize languages on the basis of where and how they allow “classic” NP construal, and how this fits into the broader range of construals in the nominal domain. Keywords: Australian languages, constituency, discontinuous constituents, non- configurationality, noun phrase, phrase-marking, phrasehood, syntax, word- marking, word order 1 Introduction It has often been argued that Australian languages show unusual syntactic flexibility in the nominal domain, and may even lack clear noun phrase struc- tures altogether – e. g., in Blake (1983), Heath (1986), Harvey (2001: 112), Evans (2003a: 227–233), Campbell (2006: 57); see also McGregor (1997: 84), Cutfield (2011: 46–50), Nordlinger (2014: 237–241) for overviews and more general dis- cussion of claims to this effect. This idea is based mainly on features -

So Far and Yet So Close: Frontier Cattle Ranching in Western Prairie Canada and the Northern Territory of Australia

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2015-06 So Far and yet so Close: Frontier Cattle Ranching in Western Prairie Canada and the Northern Territory of Australia Elofsen, Warren M. University of Calgary Press Elofson, W. M. "So Far and yet so Close: Frontier Cattle Ranching in Western Prairie Canada and the Northern Territory of Australia". University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2015. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50481 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca SO FAR AND YET SO CLOSE: FRONTIER CATTLE RANCHING IN WESTERN PRAIRIE CANADA AND THE NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA By Warren M. Elofson ISBN 978-1-55238-795-5 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Highways Byways

Highways AND Byways THE ORIGIN OF TOWNSVILLE STREET NAMES Compiled by John Mathew Townsville Library Service 1995 Revised edition 2008 Acknowledgements Australian War Memorial John Oxley Library Queensland Archives Lands Department James Cook University Library Family History Library Townsville City Council, Planning and Development Services Front Cover Photograph Queensland 1897. Flinders Street Townsville Local History Collection, Citilibraries Townsville Copyright Townsville Library Service 2008 ISBN 0 9578987 54 Page 2 Introduction How many visitors to our City have seen a street sign bearing their family name and wondered who the street was named after? How many students have come to the Library seeking the origin of their street or suburb name? We at the Townsville Library Service were not always able to find the answers and so the idea for Highways and Byways was born. Mr. John Mathew, local historian, retired Town Planner and long time Library supporter, was pressed into service to carry out the research. Since 1988 he has been steadily following leads, discarding red herrings and confirming how our streets got their names. Some remain a mystery and we would love to hear from anyone who has information to share. Where did your street get its name? Originally streets were named by the Council to honour a public figure. As the City grew, street names were and are proposed by developers, checked for duplication and approved by Department of Planning and Development Services. Many suburbs have a theme. For example the City and North Ward areas celebrate famous explorers. The streets of Hyde Park and part of Gulliver are named after London streets and English cities and counties. -

Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal Ways of Being Into Teaching Practice in Australia

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2020 Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia Lisa Buxton The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Education Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Buxton, L. (2020). Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia (Doctor of Education). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/248 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia Lisa Maree Buxton MPhil, MA, GDip Secondary Ed, GDip Aboriginal Ed, BA. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Education School of Education Sydney Campus January, 2020 Acknowledgement of Country Protocols The protocol for introducing oneself to other Indigenous people is to provide information about one’s cultural location, so that connection can be made on political, cultural and social grounds and relations established. (Moreton-Robinson, 2000, pp. xv) I would like firstly to acknowledge with respect Country itself, as a knowledge holder, and the ancients and ancestors of the country in which this study was conducted, Gadigal, Bidjigal and Dharawal of Eora Country. -

Engagement Report

Roebourne Township Structure Plan Community Engagement Report Town entry Paths Aboriginal tourism Skate park Remove asbestos Lighting river Cultural trails of people education alternative Turning Lanes diversity Clean up cemeteries Heavy vehicle diversion route Commercial near residential Old Reserve - place of respect Oldest town in the North west housing outdoor learning Cafe/communal kitchen family safe truck breakdown area safe truck breakdown look after oldies Harding River, Roebourne design for demographic 12th of May 2014 Prepared by UDLA 1 Roe St Source: Shire of Roebourne Contents Contents 3 5.0 Roebourne Community & Education Precinct 54 1.0 Introduction & Scope 4 5.2 Design Engagement Process Summary 56 1.0 Scope 4 5.3 Phase 1 - Opportunities & Directions 57 1.2 Limitations and Evolution 6 5.4 Vision 58 1.3 Town History 8 5.5 Values of the Roebourne Family Pool 61 1.4 Current Demographics & Governance Issues 10 5.6 Design Options 62 1.5 Background - Acknowledgement of Previous Studies 11 5.7 Option 1 - Redevelopment with Pool Complex 64 5.8 Option 2 - Redevelopment with Splash Pad 68 2.0 Process and Tools 12 5.8 Option 3 - Redevelopment with no water element 72 2.1 Engagement Strategy & Levels of Engagement 13 5.9 Design Option Recommendation 76 2.3 Analysis Process 14 2.4 Participants 22 6.0 Conclusion of wider context 78 Appendix A | Engagement Meetings 82 3.0 Findings - Vision 24 Appendix B | All findings - Roebourne Structure Plan 84 3.2 Key Recommendations 26 Appendix C | All findings - Roebourne Community and Education -

Aramac , Queensland

REDFORD RRY HA LE DRIVE T N S L A N D AT Q U E E C A C , M A R A www.harryredford.com.au PROUDLY BROUGHT TO YOU BY: BARCALDINE REGIONAL COUNCIL 07 4651 5600 BARCALDINE EMAIL: [email protected] PO BOX 191, Barcaldine Qld 4725 REGIONAL COUNCIL the legend Harry Redford Henry Arthur Redford is commonly known as “Captain Starlight” in Australian folklore. Henry or Harry Redford was born in Mudgee, NSW, of an Irish convict father and a “Currency Lass”. He was the youngest of eleven children. His family were landowners from the Hawkesbury River area. The AsMyth is most often the case As Harry Redford was an expert bushman and drover, he with history, characters are worked as head teamster transporting stores to many romanticised and it soon becomes isolated properties in Western Queensland. He soon realised that many of these properties were so large stock would impossible to sort myth from fact. not be missed for some time due to the isolation. Harry Redford is credited as being the inspiration behind Rolf Boldrewood’s Bowen Downs, Aramac fitted this category and book, “Robbery Under Arms”. Who was so Redford devised a plan to steal cattle when the Bowen Downs mustering camp was working on the Starlight? Was it Redford or was it a figment opposite end of the run. of the author’s imagination. Another myth surrounding Redford is that he opened up In March 1870, Redford and four others stole uncharted territory along the Strzlechi Track. between 600-1000 head of cattle, including an imported white bull belonging to the Scottish However, some believe it was John Costello, Australian Company, Bowen Downs, which a friend of the Durack’s of “Kings in Grass stretched some 140 miles along the Thomson River Castle” fame.