Cases, Arguments, Verbs in Abkhaz, Georgian and Mingrelian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Khevsur and Tush and the Status of Unusual Phenomena in Corpora Author(S): Thomas R

Khevsur and Tush and the status of unusual phenomena in corpora Author(s): Thomas R. Wier Proceedings of the 37th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: Special Session on Languages of the Caucasus (2013), pp. 96-110 Editors: Chundra Cathcart, Shinae Kang, and Clare S. Sandy Please contact BLS regarding any further use of this work. BLS retains copyright for both print and screen forms of the publication. BLS may be contacted via http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/bls/. The Annual Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society is published online via eLanguage, the Linguistic Society of America's digital publishing platform. Khevsur and Tush and the Status of Unusual Phenomena in Corpora THOMAS R. WIER University of Chicago Introduction Recent years have seen an increasing realization of the threat posed by language loss where, according to some estimates, upwards of ninety percent of all lan- guages may go extinct within the next century (Nettle & Romaine 2002). What is less often realized, much less discussed, is the extent to which linguistic diversity that falls within the threshold of mutual intelligibility is also diminishing. This is especially true of regions where one particular language variety is both widely spoken and holds especially high prestige across many different social classes and communities. In this paper, we will examine two such dialects of Georgian: Khevsur and Tush, and investigate what corpora-based dialectology can tell us about phylogenetic and typological rarities found in such language varieties. 1 Ethnolinguistic Background Spoken high in the eastern Caucasus mountains along the border with Chechnya and Ingushetia inside the Russian Federation, for many centuries, Khevsur and Tush have been highly divergent dialects of Georgian, perhaps separate lan- guages, bearing a relationship to literary Georgian not unlike that of Swiss German and Hochdeutsch (see map, from Hewitt 1995:vi). -

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

Lexicographic Potential of the Georgian Dialect Corpus

LexicographicLexicographic Potential Potential of ofthe the Georgian Georgian Dialect Dialect Corpus Corpus MarinaMarina Beridze, Beridze, David David Nadaraia Nadaraia Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Arn. Chikobava Institute of Linguistics e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The project Linguistic Portrait of Georgia envisages various aspects of documentation of Georgian linguistic reality by means of corpus methodologies. This title is an umbrella for three large-scale projects within the framework of which The Georgian Dialect Corpus – GDC (http://corpora.co) was developed. Presently, the architecture and text base of the corpus have been designed, being permanently developed and updated. Besides, the lexicographic base of the corpus is organized, agglomerating data from printed dialect dictionaries. The lexical stock of the corpus is presented based on text, lexicographic and encyclopaedic data. The total quantity of tokens in the corpus is estimated to be up to 2 000 000, while the lexicographic base has 60 000 items (lemmas with entries) by now; this quantity is considerably increased owing to phonetic and grammatical variations, frequently associated with a single lexical item. Keywords: Georgian Dialect Corpus; lexicographic base; encyclopaedic data 1 Georgian Dialect Corpus: General Characteristics The Georgian Dialect Corpus (GDC) was developed as a means for documentation and study of Georgian linguistic diversity (Beridze, Nadaraia 2009: 25; Beridze, Lordkipanidze, Nadaraia: 2015-1, 323). Consisting of several components, this is a reference resource, which, with respect to its interdisciplinary objectives, considerably differs from other similar corpora. The principal difference is that GDC has corpus and library modes of text access; it integrates the lexicographic base, a prospective universal lexicographic base of the Georgian language. -

PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL of KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES N O 27 — 2017 2

1 PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL OF KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES N o 27 — 2017 2 E DITOR- IN-CHIEF David KOLBAIA S ECRETARY Sophia J V A N I A EDITORIAL C OMMITTEE Jan M A L I C K I, Wojciech M A T E R S K I, Henryk P A P R O C K I I NTERNATIONAL A DVISORY B OARD Zaza A L E K S I D Z E, Professor, National Center of Manuscripts, Tbilisi Alejandro B A R R A L – I G L E S I A S, Professor Emeritus, Cathedral Museum Santiago de Compostela Jan B R A U N (†), Professor Emeritus, University of Warsaw Andrzej F U R I E R, Professor, Universitet of Szczecin Metropolitan A N D R E W (G V A Z A V A) of Gori and Ateni Eparchy Gocha J A P A R I D Z E, Professor, Tbilisi State University Stanis³aw L I S Z E W S K I, Professor, University of Lodz Mariam L O R T K I P A N I D Z E, Professor Emerita, Tbilisi State University Guram L O R T K I P A N I D Z E, Professor Emeritus, Tbilisi State University Marek M ¥ D Z I K (†), Professor, Maria Curie-Sk³odowska University, Lublin Tamila M G A L O B L I S H V I L I, Professor, National Centre of Manuscripts, Tbilisi Lech M R Ó Z, Professor, University of Warsaw Bernard OUTTIER, Professor, University of Geneve Andrzej P I S O W I C Z, Professor, Jagiellonian University, Cracow Annegret P L O N T K E - L U E N I N G, Professor, Friedrich Schiller University, Jena Tadeusz Ś W I Ę T O C H O W S K I (†), Professor, Columbia University, New York Sophia V A S H A L O M I D Z E, Professor, Martin-Luther-Univerity, Halle-Wittenberg Andrzej W O Ź N I A K, Professor, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 3 PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL OF KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES No 27 — 2017 (Published since 1991) CENTRE FOR EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES FACULTY OF ORIENTAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW WARSAW 2017 4 Cover: St. -

Shota Rustaveli Theatre and Film Georgia State University Faculty of Art Sciences, Media and Management Khatuna Damchidze Tbilis

Shota Rustaveli Theatre and Film Georgia State University Faculty of Art Sciences, Media and Management Khatuna Damchidze Tbilisi 0108 Georgia Dance Dialects of West Georgia (Abkhazian, Acharian, Laz-Shavshetian, Megrelian, Rachan) and Main Ethnocoreological Aspects of Their Interrelation Abstract of the thesis work for the Academic degree Dr. of Arts (Phd) Scientific supervisor: Dr. of Arts Ana Samsonadze Tbilisi 2019 1 GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE WORK Actuality of the themes: Today, when the world is overwhelmed by the irreversible process of globalization, when the difference between the nations is being eliminated, the problem of maintaining originality is fairly acute. This problem is more obvious on the example of little countries such as Georgia. Had it not been the cultural heritage (material and intangible) from ancient times to this day, Georgia would not have occupied the place it holds now, in the world culture. As an object of cultural heritage, Georgian national choreography holds a special place and is of particular importance. Originality of Georgian folk dance is manifested in its ethnic variety which, on the one hand, exists as absolutely different dance tradition and on the other hand, as part of common Georgian folklore. Although certain number of dialects, from the standpoint of dance lexicon has disappeared (Imeretian, Lechkhumian); diversity of dance dialects is observed on a geographically small territory of West Georgia West Georgian circle of dialects comprises Svan, Rachan, Abkhazian, Megrelian, Gurian and Laz folk choreography1. One of the most important issues of choreology to be researched today is ascertainment and classification of separate dance dialects and elucidation of their interrelations. -

|Ohn Benjamins Publishing Company

|ohn Benjamins Publishing Company This is a contribution {rom h{ood in the Languages of Eurt:pe. Edited by Björn Rothstein and Rolf Thieroff O 2010. )ohn Benjamins Publishing Cornpany This electronic hle may not be altered in any rval'. The author(s) of this article islare permitted to use this PDF file to generate printed copies to be used by rvay of ofprints, for their personal use only. Permission is granted bv the publishers to post this file on a closed server rvhich is accessible to members (str.rdents aird staff) orrly of the author's/s'institute, it is not permitted to post this PDF on the open internet. For any other use of this material prior ivritten pernrission s}rould be obtained fr:om the publishers or througlt the Copy.right Cleararrce Center (Ibr USA: wnrt-.copyT ight.corn). Please contact [email protected] or consuit our rvebsite: wwir'.beniamins.com Tables of Contents, ahstracts and guidelirles are available at rmv'.benjamins.com Mood 1n Modern Georgian* Winfried Boeder Oldenburg r. Introduction Ceor:gian is one of the Karl-r,elian (South Caucasian) langtiages which ar:e spoken in a relatively compact area to tl're south of the Caucasus ridge rvhere (as tär as lve knou') the,v have alwa,ys been in conlact lvith each other: Georgian in the easl, Megrelian (or Min- greiian) in the rvest and Svan in the north-western mountains of Georgia; Laz is mainly spoken in an area ad;'acent to the Black Sea between'liabzon and Baturni. Only Georgian has a long-standing 1500 year old rvritten tradition. -

Batumi Linguocultural Digital Archive (Contemporary Technological Achievements for the Database Arrangement of the Folklore Resources)

M.Tandaschwili, R. Khalvashi, Kh. Beridze, M. Khakhutaishvili, N. Tsetskhladze, Batumi # 10. 2010 Linguocultural Digital Archive pp. 52-68 Manana Tandaschwili Frankfurt Goethe University R. Khalvashi, Kh. Beridze, M. Khakhutaishvili, N. Tsetskhladze Batumi State University Batumi Linguocultural Digital Archive (Contemporary Technological Achievements for the Database Arrangement of the Folklore Resources) Abstract The evolution of the new forms of the scientific communication and development of the web technologies and global networking gave the scholars an excellent opportunity to rapidly and effectively use academic digital resources, the number of which is constantly increasing. Establishment of the OR (Open-Resource) and introduction of the RE (Resource Exchange) supported development of the infrastructure for the digital archives. That, in its own right, became a fast and efficient instrument for the use of scholarly resources. It has essentially changed the research procedures in the 21st century. The researchers now are able to make use of the ‘open and merge’ approach to their resources. Creation of the global library has become a new opportunity of the international scholarly communication. The joint scientific project Batumi Linguocultural Digital Archieve (BaLDAR) implemented jointly by Batumi Shota Rustaveli State University and Goethe Frankfurt University is sponsored by the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation. The project is a result of the international cooperation and aims to introduce new forms of the scientific communication, which will support multidisciplinary research development. The paper studies the significance of the establishment digital archives in Georgia. It outlines the themes of the resources that have been developed within the project framework. Key words: web technologies; Linguoculturalizm; Digital Archieve. -

Deponent Verbs in Georgian Kevin Tuite (Université De Montréal)

Deponent verbs in Georgian Kevin Tuite (Université de Montréal) 0. Introduction. In the summer of 2000, while on a research trip to Georgia, I came across the following cartoon in a Tbilisi newspaper. Here is the text with a translation: Waiter: supši rat’om ipurtxebit? (Why do you keep spitting in the soup?) Customer: vsinǰav, cxelia tu ara. (I’m testing if it’s hot or not.) Waiter: ??? Customer: čemi coli q’oveltvis egre amoc’mebs utos. (My wife always checks the iron like this.) Leaving aside the political incorrectness — on several levels — of the content of the cartoon, let us make use of it as a source of linguistic data. The verb in the first line, i-purtx-eb-i-t “you [pl/polite] spit”, is formally in the passive voice; its 3rd-person subject form would be i- purtx-eb-a. Its morphology contrasts with that of the transitive a-purtx- eb-s in exactly the same way as, say, the passive (k’ari) i-ɣ-eb-a “(the door) is opened” is opposed to the active (k’ars) a-ɣ-eb-s “s/he opens (the door)”. If the meaning of a-purtx-eb-s is “s/he spits”, one would expect the first line of the above dialogue to mean something along the lines of “Why are you being spit into the soup?”, which is manifestly not the case. The Explanatory Dictionary of the Georgian Language (KEGL) glosses ipurtxeba “spits continually, sprays spit all the time (from the mouth)” (erttavad apurtxebs, c’ara-mara purtxs isvris (p’iridan)); according to Tschenkéli’s dictionary, it means “(dauernd) spucken”. -

For the Annotation of Titlo Diacritic

Irina LOBJANIDZE Associate Professor Ilia State University Tbilisi, Georgia For the annotation of Titlo Diacritic Abstract: The paper describes different levels of annotation used in the Corpus of Modern, Middle and Old Georgian Texts. Aiming at building a new, extensive and representative tool for Georgian language the Corpus was compiled under the financial support of the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation and the Ilia State University (AR/266/1-31/13). In particular, the Corpus of Georgian language is envisaged as collecting a substantial amount of data needed for research. The scope and representativeness of texts included as well as free accessibility to it makes the corpus one of the most necessary tools for the study of different texts in Modern, Middle and Old Georgian (see, http://corpora.iliauni.edu.ge/). The corpus consists of different kind of texts, mainly: a) Manuscript- based publications; b) Reprints; c) Previously unpublished manuscripts and; d) Previously published manuscripts and covers Modern, Middle and Old Georgian. The paper presents the research area, the design and structure and applications related to the compilation of the corpus, in particular, different levels of annotation as meta-data, structural mark-up and linguistic annotation at word-level, especially, from the viewpoint of Titlo Diacritic. This paper is structured as follows: Section 1 includes background and research questions; Section 2 presents a methodological approach and briefly summarizes its theoretical prerequisites; Section 3 includes the findings and hypothesis, which refers generally to the differences between the annotation of Modern and Old Georgian texts; and Section 4 presents the answers to the research questions. -

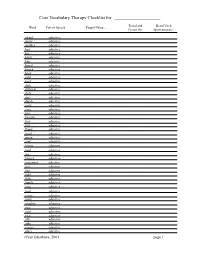

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Split-Intransitive Languages and the Unaccusative Hypothesis

31 DEFINING TRANSITIVITY AND INTRANSITIVITY: SPLIT-INTRANSITIVE LANGUAGES AND THE UNACCUSATIVE HYPOTHESIS ASIER ALCÁZAR University of Southern California, Los Angeles 0. Proposals 0.1 Basque is not an ergative language; it is split-intransitive. * Against the standard typological claim (contra Comrie 1981, Dixon 1994, Primus 1999) 0.2 Unergative verbs are not always intransitive (they can be transitive: e.g. Basque). * Against the claim in the Unaccusative Hypothesis (contra Perlmutter 1978, Burzio 1986) 0.3 Split-intransitivity signals that unergatives are transitive. * Novel claim: split-intransitivity has been otherwise considered an anomalous pattern. 1. INTRODUCTION: INTRANSITIVE VERBS WITH TRANSITIVE LOOKS (I.E. 1A). Basque is often presented as a splendid example of ergativity (Comrie 1981, Dixon 1994, Primus 1999 among many). Tradi- tionally, ergative languages differ from accusative languages in the verbal argument they mark. Erga- tive languages mark the subject of transitives (compare the girl in 2 with 1b) and accusative lan- guages mark the object of transitives (e.g. Latin/Romance; see the feminine singular pronoun in 4). However, the axioms in the typological classification of languages would by definition declare Basque to be of type split-intransitive (e.g. like Guarani, Gregorez and Suarez 1967 cfr. Primus 1999; or Slave, Rice 1991). For Basque has a class of intransitive verbs (1a) whose argument is marked exactly as the subject of transitives (2). Basque intransitives: (1) a. Neskatil-ak dei-tu du b. Neskatil-a ailega-tu da girl-Erg.Sg call-Per have.3Sg_3Sg girl-Abs.Sg arrive-Per be.3Sg ‘The girl called’ ‘The girl arrived’ Basque transitives: (2) Neskatil-ak izozki-a amai-tu du girl-Erg.Sg ice-cream-Abs.Sg finish-Per have.3Sg_3Sg ‘The girl finished her ice-cream’ Spanish intransitives: (3) a. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b93p0xs Author Gurevich, Olga Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich B.A. (University of Virginia) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2002 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Johanna Nichols Spring 2006 The dissertation of Olga I Gurevich is approved: Co-Chair Date Co-Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2006 Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Copyright 2006 by Olga I Gurevich 1 Abstract Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair, Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Linguistic theories can be distinguished based on how they represent the construc- tion of linguistic structures. In \bottom-up" models, meaning is carried by small linguistic units, from which the meaning of larger structures is derived. By contrast, in \top-down" models the smallest units of form need not be individually meaningful; larger structures may determine their overall meaning and the selection of their parts. Many recent developments in psycholinguistics provide empirical support for the latter view. This study combines intuitions from Construction Grammar and Word-and-Para- digm morphology to develop the framework of Constructional Morphology.