Glimpses of Handel in the Choral-Orchestral Psalms of Mendelssohn by Zachary D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Najaarsconcert 2018 2

NAJAARSCONCERT 2018 2 Welkom Beste concertbezoeker, Ik heet u namens de Oratoriumvereniging van harte welkom bij ons najaarsconcert in deze prachtige Martinikerk van Bolsward. Dit concert staat in het teken van Jacob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (geboren 3 februari 1809 en overleden op 4 november 1847). Hij was een Duitse componist, pianist, organist en dirigent in de vroeg romantische periode. Mendelssohn schreef symfonieën, concerten, oratoria, pianomuziek en kamermuziek. Hij vierde zijn successen in Duitsland en liet de muziek van Johann Sebastian Bach herleven. Vanmiddag voeren wij twee werken van hem uit: het Lobgesang en Psalm 42. Verder zal onze organist nog een sonate van Mendelssohn spelen. Onze uitvoering vanmiddag is een bijzondere uitvoering. Zoals u ziet zijn het koor, het orkest en de solisten geplaatst op een speciaal voor deze uitvoering gemaakt podium vlak voor het prachtige kerkorgel, dat meewerkt aan de uitvoering. U, als publiek zit nu ook andersom. Wij willen vandaag als koor ervaren hoe deze opstelling bevalt. Mocht dat positief zijn, dan zullen we in de toekomst waarschijnlijk vaker gebruik gaan maken van deze opstelling. In dit concertboekje kunt u verder alle informatie over dit concert lezen. Ook is er een plattegrond opgenomen waarop staat aangegeven waar de toiletten zijn en waar de nooduitgangen zich bevinden. Graag deze plattegrond voor aanvang van het concert goed bekijken. Volgend jaar voeren wij in de week voor Pasen weer tweemaal de Matthäus-Passion uit en in het najaar de volledige uitvoering van de Messiah van Händel. We hopen u dan ook als luisteraar te mogen begroeten. Met vriendelijke groeten, G.J.Ankersmit (voorzitter) Heeft u vandaag genoten van onze uitvoering, dan is het misschien een goed idee om vriend van onze Oratoriumvereniging te worden. -

Glimpses of Handel in the Choral-Orchestral Psalms of Mendelssohn

Glimpses of Handel in the Choral-Orchestral Psalms of Mendelssohn Zachary D. Durlam elix Mendelssohn was drawn to music of the Baroque era. His early training Funder Carl Friedrich Zelter included study and performance of works by Bach and Handel, and Mendelssohn continued to perform, study, and conduct compositions by these two composers throughout his life. While Mendels- sohn’s regard for J. S. Bach is well known (par- ticularly through his 1829 revival of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion), his interaction with the choral music of Handel deserves more scholarly at ten- tion. Mendelssohn was a lifelong proponent of Handel, and his contemporaries attest to his vast knowledge of Handel’s music. By age twenty- two, Mendelssohn could perform a number of Handel oratorio choruses from memory, and two years later, fellow musician Carl Breidenstein remarked that “[Mendelssohn] has complete knowledge of Handel’s works and has captured their spirit.”1 Zachary D. Durlam Director of Choral Activities Assistant Professor of Music University of Wisconsin Milwaukee [email protected] 28 CHORAL JOURNAL Volume 56 Number 10 George Frideric Handel Felix Mendelssohn Glimpses of Handel in the Choral- Mendelssohn’s self-perceived familiarity with Handel’s Mendelssohn’s Psalm 115 compositions is perhaps best summed up in the follow- and Handel’s Dixit Dominus ing anecdote about English composer William Sterndale During an 1829 visit to London, Mendelssohn was Bennett: allowed to examine Handel manuscripts in the King’s Library. Among these scores, he discovered and -

The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary

Alternative Services The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary Anglican Book Centre Toronto, Canada Copyright © 1985 by the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada ABC Publishing, Anglican Book Centre General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada 80 Hayden Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4Y 3G2 [email protected] www.abcpublishing.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Acknowledgements and copyrights appear on pages 925-928, which constitute a continuation of the copyright page. In the Proper of the Church Year (p. 262ff) the citations from the Revised Common Lectionary (Consultation on Common Texts, 1992) replace those from the Common Lectionary (1983). Fifteenth Printing with Revisions. Manufactured in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Anglican Church of Canada. The book of alternative services of the Anglican Church of Canada. Authorized by the Thirtieth Session of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada, 1983. Prepared by the Doctrine and Worship Committee of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada. ISBN 978-0-919891-27-2 1. Anglican Church of Canada - Liturgy - Texts. I. Anglican Church of Canada. General Synod. II. Anglican Church of Canada. Doctrine and Worship Committee. III. Title. BX5616. A5 1985 -

Cantate Concert Program May-June 2014 "Choir + Brass"

About Cantate Founded in 1997, Cantate is a mixed chamber choir comprised of professional and avocational singers whose goal is to explore mainly a cappella music from all time periods, cultures, and lands. Previous appearances include services and concerts at various Chicago-area houses of worship, the Chicago Botanic Garden’s “Celebrations” series and at Evanston’s First Night. antate Cantate has also appeared at the Chicago History Museum and the Chicago Cultural Center. For more information, visit our website: cantatechicago.org Music for Cantate Choir + Br ass Peter Aarestad Dianne Fox Alan Miller Ed Bee Laura Fox Lillian Murphy Director Benjamin D. Rivera Daniella Binzak Jackie Gredell Tracy O’Dowd Saturday, May 31, 2014 7:00 pm Sunday, June 1, 2014 7:00 pm John Binzak Dr. Anne Heider Leslie Patt Terry Booth Dennis Kalup Candace Peters Saint Luke Lutheran Church First United Methodist Church Sarah Boruta Warren Kammerer Ellen Pullin 1500 W Belmont, Chicago 516 Church Street, Evanston Gregory Braid Volker Kleinschmidt Timothy Quistorff Katie Bush Rose Kory Amanda Holm Rosengren Progr am Kyle Bush Leona Krompart Jack Taipala Joan Daugherty Elena Kurth Dirk Walvoord Canzon septimi toni #2 (1597) ....................Giovanni Gabrieli (1554–1612) Joanna Flagler Elise LaBarge Piet Walvoord Surrexit Christus hodie (1650) .......................... Samuel Scheidt (1587–1654) Canzon per sonare #1 (1608) ..............................................................Gabrieli Thou Hast Loved Righteousness (1964) .........Daniel Pinkham (1923–2006) About Our Director Sonata pian’ e forte (1597) ...................................................................Gabrieli Benjamin Rivera has been artistic director of Cantate since 2000. He has prepared and conducted choruses at all levels, from elementary Psalm 114 [116] (1852) ................................. Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) school through adult in repertoire from gospel, pop, and folk to sacred polyphony, choral/orchestral masterworks, and contemporary pieces. -

TRANSLATORS WITHOUT BORDERS a Community Translating to Save Lives

The Voice of Interpreters and Translators THE ATA Nov/Dec 2015 Volume XLIV Number 9 CHRONICLE TRANSLATORS WITHOUT BORDERS A Community Translating To Save Lives PEMT Yourself! Don't Leave Money You're Owed on the Table! Beyond Post-Editing: Advances in Interactive Translation Environments Switching from a Laptop to a Tablet: An Interpreter’s Experience A Publication of the American Translators Association CAREERS at the NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY inspiredTHINKING When in the office, NSA language analysts develop new perspectives NSA has a critical need for individuals with the on the dialect and nuance of foreign language, on the context and following language capabilities: cultural overtones of language translation. • Arabic • Chinese We draw our inspiration from our work, our colleagues and our lives. • Farsi During downtime we create music and paintings. We run marathons • Korean and climb mountains, read academic journals and top 10 fiction. • Russian • Spanish Each of us expands our horizons in our own unique way and makes • And other less commonly taught languages connections between things never connected before. APPLY TODAY At the National Security Agency, we are inspired to create, inspired to invent, inspired to protect. U.S. citizenship is required for all applicants. NSA is an Equal Opportunity Employer and abides by applicable employment laws and regulations. All applicants for employment are considered without regard to age, color, disability, genetic information, national origin, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, marital status, or status as a parent. Search NSA to Download WHERE INTELLIGENCE GOES TO WORK® 14CNS-10_8.5x11(live_8x10.5).indd 1 9/16/15 10:44 AM Nov/Dec 2015 Volume XLIV CONTENTS Number 9 FEATURES 19 Beyond Post-Editing: Advances in Interactive 9 Translation Environments Translators without Borders: Post-editing was never meant A Community Translating to be the future of machine to Save Lives translation. -

Translation, Reputation, and Authorship in Eighteenth-Century Britain

Translation, Reputation, and Authorship in Eighteenth-Century Britain by Catherine Fleming A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Catherine Fleming 2018 Translation, Reputation, and Authorship in Eighteenth-Century Britain Catherine Fleming Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This thesis explores the reputation-building strategies which shaped eighteenth-century translation practices by examining authors of both translations and original works whose lives and writing span the long eighteenth century. Recent studies in translation have often focused on the way in which adaptation shapes the reception of a foreign work, questioning the assumptions and cultural influences which become visible in the process of transformation. My research adds a new dimension to the emerging scholarship on translation by examining how foreign texts empower their English translators, offering opportunities for authors to establish themselves within a literary community. Translation, adaptation, and revision allow writers to set up advantageous comparisons to other authors, times, and literary milieux and to create a product which benefits from the cachet of foreignness and the authority implied by a pre-existing audience, successful reception history, and the standing of the original author. I argue that John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Eliza Haywood, and Elizabeth Carter integrate this legitimizing process into their conscious attempts at self-fashioning as they work with existing texts to demonstrate creative and compositional skills, establish kinship to canonical authors, and both ii construct and insert themselves within a literary canon, exercising a unique form of control over their contemporary reputation. -

Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the Rise of the Cäcilien-Verein

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2020 Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein Nicholas Bygate Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bygate, Nicholas, "Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein" (2020). WWU Graduate School Collection. 955. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/955 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein By Nicholas Bygate Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Bertil van Boer Dr. Timothy Fitzpatrick Dr. Ryan Dudenbostel GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Interim Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. -

Translation and Nation

TRANSLATION AND NATION: THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY IN THE AMERICAN RENAISSANCE A Dissertation by KOHEI FURUYA Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Larry J. Reynolds Committee Members, Richard Golsan David McWhirter Mary Ann O’Farrell Head of Department, Nancy Warren May 2015 Major Subject: English Copyright 2015 Kohei Furuya ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the significance of translation in the making of American national literature. Translation has played a central role in the formation of American linguistic, literary, cultural, and national identity. The authors of the American Renaissance were multilingual, involved in the cultural task of translation in many different ways. But the importance of translation has been little examined in American literary scholarship, the condition of which has been exclusively monolingual. This study makes clear the following points. First, translation served as an important agency in the building of American national language, literature, and culture. Second, the conception of translation as a means for domesticating foreign influences in antebellum American literary culture was itself a translation of a traditionally European idea of translation since the Renaissance, and more specifically, of the modern German concept of it. Third, despite its ethnocentric, nationalistic, and imperialistic tendency, translation sometimes complicated the identity-formation process. The American Renaissance writers worked in the complex international culture of translation in an age of world literature, a nationalist-cosmopolitan concept that Goethe promoted in the early nineteenth century. Those American authors’ texts often take part in and sometimes come up against the violence of translation, which obliterates the marks of otherness in foreign languages and cultures. -

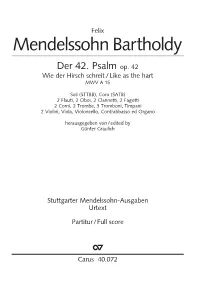

Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Der 42. Psalm op. 42 Wie der Hirsch schreit /Like as the hart MWV A 15 Soli (STTBB), Coro (SATB) 2 Flauti, 2 Oboi, 2 Clarinetti, 2 Fagotti 2 Corni, 2 Trombe, 3 Tromboni, Timpani 2 Violini, Viola, Violoncello, Contrabbasso ed Organo herausgegeben von/edited by Günter Graulich Stuttgarter Mendelssohn-Ausgaben Urtext Partitur/Full score C Carus 40.072 Inhalt Vorwort Dem heutigen Musikbetrieb dient Felix Mendelssohn Bar- liegen auch solche von Händel in Mendelssohns Bearbei- Vorwort / Foreword / Avant-propos 3 tholdy (1809–1847), der „romantische Klassizist“ (A. Ein- tungen und Ausgaben vor, so das Dettinger Te Deum, Acis stein) oder „klassizistische Romantiker“ (P. H. Lang), nur und Galatea sowie Israel in Ägypten. Hier hat Mendelssohn Faksimiles 8 mit einem schmalen Anteil seines reichen Werkes: mit Sin- nicht nur die Partituren nach den Originalquellen revidiert, fonien, Ouvertüren, dem Violin- und dem Klavierkonzert, sondern auch obligate Orgelpartien ausgeschrieben. der Musik zu Shakespeares Sommernachtstraum und weni- 1. Coro (SATB) 11 ger Kammermusik (z.B. dem Streicheroktett), Aufführun- Mendelssohn selbst hat sowohl geistliche A-cappella- Wie der Hirsch schreit gen seines gewichtigen und einst populären Oratorien- Musik „im alten Stil“ geschrieben als auch Werke mit As the hart longs spätlings Elias op. 70 (1846) sind heute selten. Und sein bei instrumentaler Begleitung. In der ersten Gruppe ragen das weitem originellstes Vokalwerk, die Erste Walpurgisnacht großartige achtstimmige Te Deum (1826) sowie die Mo- 2. Aria (Solo S) 26 op. 60 nach Goethe (zwei Fassungen: 1831 und 1843), von tetten op. 69, drei Psalmen op. 78 und Sechs Sprüche für Meine Seele dürstet nach Gott Berlioz gerühmt und ein Gipfel des Oratorienschaffens Doppelchor op. -

ODE 1201-1 DIGITAL.Indd

ESTONIAN PHILHARMONIC CHAMBER CHOIR MENDELSSOHN DANIEL REUSS PSALMS KREEK 1 FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–1847) 1 Psalm 100 “Jauchzet dem Herrn, alle Welt”, Op. 69/2 4’27 CYRILLUS KREEK (1889–1962) 2 Psalm 22 “Mu Jumal! Mikspärast oled Sa mind maha jätnud?” 4’27 FELIX MENDELSSOHN 3 Psalms, Op. 78: 3 Psalm 2 “Warum toben die Heiden” 7’29 4 Psalm 43 “Richte mich, Gott” 4’31 5 Psalm 22 “Mein Gott, warum hast du mich verlassen?” * 8’08 * TIIT KOGERMAN, tenor CYRILLUS KREEK 6 Psalm 141 “Issand, ma hüüan Su poole” 2’27 7 Psalm 104 “Kiida, mu hing, Issandat!” 2’28 8 “Õnnis on inimene” 3’26 9 Psalm 137 “Paabeli jõgede kaldail” 6’40 FELIX MENDELSSOHN 10 “Hebe deine Augen” (from: Elijah, Op. 70) 2’16 11 “Denn er hat seinen Engeln befohlen” (from: Elijah, Op. 70) 3’32 12 “Wie selig sind die Toten”, Op. 115/1 3’30 2 CYRILLUS KREEK Sacred Folk Songs: 13 “Kui suur on meie vaesus” 2’43 14 “Jeesus kõige ülem hää” 1’54 15 “Armas Jeesus, Sind ma palun” 2’31 16 “Oh Jeesus, sinu valu” 2’03 17 “Mu süda, ärka üles” 1’43 ESTONIAN PHILHARMONIC CHAMBER CHOIR DANIEL REUSS, conductor Publishers: Carus-Verlag (Mendelssohn), SP Muusikaprojekt (Kreek) Recording: Haapsalu Dome Church, Estonia, 14–17.9.2009 Executive Producer: Reijo Kiilunen Recording and Post Production: Florian B. Schmidt ℗ 2012 Ondine Oy, Helsinki © 2012 Ondine Oy, Helsinki Booklet Editor: Elke Albrecht Translations to English: Kaja Kappel/Phyllis Anderson (liner notes), Kaja Kappel (tracks 13-17) Photos: Kaupo Kikkas (Niguliste Church in Tallinn – Front Cover; Daniel Reuss); Tõnis Padu (Haapsalu Dome Church) Design: Armand Alcazar 3 PSALMS BY FELIX MENDELSSOHN Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809–1847) was born in Germany into a family with Jewish roots; his grandfather was the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, his father a banker. -

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Sielminger Straße 51 Herr, Gedenke Nicht Op

Mendelssohn Bartholdy Das geistliche Vokalwerk · Sacred vocal music · Musique vocale sacrée Carus Alphabetisches Werkverzeichnis · Works listed alphabetically Adspice Domine. Vespergesang op. 121 25 Hymne op. 96 19, 27 Abendsegen. Herr, sei gnädig 26 Ich harrete des Herrn 30 Das geistliche Vokalwerk · The sacred vocal works · La musique vocale sacrée 4 Abschied vom Walde op. 59,3 33 Ich weiche nicht von deinen Rechten 29 Die Stuttgarter Mendelssohn-Ausgaben · The Stuttgart Mendelssohn Editions Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein 15 Ich will den Herrn preisen 29 Les Éditions Mendelssohn de Stuttgart 8 Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr 26 Jauchzet dem Herrn in A op. 69,2 28 Orchesterbegleitete Werke · Works with orchestra · Œuvres avec orchestre Alleluja (aus Deutsche Liturgie) 26, 27 Jauchzet dem Herrn in C 30 Amen (aus Deutsche Liturgie) 26, 27 Jauchzet Gott, alle Lande 29 – Die drei Oratorien · The three oratorios · Les trois oratorios 11 Auf Gott allein will hoffen ich 26 Jesu, meine Freude 17 – Die fünf Psalmen · The five psalms · Les cinq psaumes 13 Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir op. 23,1 27 Jesus, meine Zuversicht 30 – Die acht Choralkantaten · The eight chorale cantatas · Les huit cantates sur chorals 15 Ave Maria op. 23,2 27 Jube Domne 31 – Lateinische und deutsche Kirchenmusik · Latin and German church music Ave maris stella 24 Kyrie in A (aus Deutsche Liturgie) 26, 27 Musique sacrée latine et allemande 19 Beati mortui / Selig sind op. 115,1 25 Kyrie in c 31 Werke für Solostimme · Works for solo voice · Œuvres pour voix solo 24 Cantique pour l’Eglise Wallonne 26, 31 Kyrie in d 21 Christe, du Lamm Gottes 15 Lasset uns frohlocken op. -

Living Currency, Pierre Klossowski, Translated by Vernon Cisney, Nicolae Morar and Daniel

LIVING CURRENCY ALSO AVAILABLE FROM BLOOMSBURY How to Be a Marxist in Philosophy, Louis Althusser Philosophy for Non-Philosophers, Louis Althusser Being and Event, Alain Badiou Conditions, Alain Badiou Infinite Thought, Alain Badiou Logics of Worlds, Alain Badiou Theoretical Writings, Alain Badiou Theory of the Subject, Alain Badiou Key Writings, Henri Bergson Lines of Flight, Félix Guattari Principles of Non-Philosophy, Francois Laruelle From Communism to Capitalism, Michel Henry Seeing the Invisible, Michel Henry After Finitude, Quentin Meillassoux Time for Revolution, Antonio Negri The Five Senses, Michel Serres Statues, Michel Serres Rome, Michel Serres Geometry, Michel Serres Leibniz on God and Religion: A Reader, edited by Lloyd Strickland Art and Fear, Paul Virilio Negative Horizon, Paul Virilio Althusser’s Lesson, Jacques Rancière Chronicles of Consensual Times, Jacques Rancière Dissensus, Jacques Rancière The Lost Thread, Jacques Rancière Politics of Aesthetics, Jacques Rancière Félix Ravaisson: Selected Essays, Félix Ravaisson LIVING CURRENCY Followed by SADE AND FOURIER Pierre Klossowski Edited by Vernon W. Cisney, Nicolae Morar and Daniel W. Smith Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Collection first published in English 2017 © Copyright to the collection Bloomsbury Academic, 2017 Vernon W. Cisney, Nicolae Morar, and Daniel W. Smith have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Editors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.