Normalization of Power Spectral Density Estimates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measurement Techniques of Ultra-Wideband Transmissions

Rec. ITU-R SM.1754-0 1 RECOMMENDATION ITU-R SM.1754-0* Measurement techniques of ultra-wideband transmissions (2006) Scope Taking into account that there are two general measurement approaches (time domain and frequency domain) this Recommendation gives the appropriate techniques to be applied when measuring UWB transmissions. Keywords Ultra-wideband( UWB), international transmissions, short-duration pulse The ITU Radiocommunication Assembly, considering a) that intentional transmissions from devices using ultra-wideband (UWB) technology may extend over a very large frequency range; b) that devices using UWB technology are being developed with transmissions that span numerous radiocommunication service allocations; c) that UWB technology may be integrated into many wireless applications such as short- range indoor and outdoor communications, radar imaging, medical imaging, asset tracking, surveillance, vehicular radar and intelligent transportation; d) that a UWB transmission may be a sequence of short-duration pulses; e) that UWB transmissions may appear as noise-like, which may add to the difficulty of their measurement; f) that the measurements of UWB transmissions are different from those of conventional radiocommunication systems; g) that proper measurements and assessments of power spectral density are key issues to be addressed for any radiation, noting a) that terms and definitions for UWB technology and devices are given in Recommendation ITU-R SM.1755; b) that there are two general measurement approaches, time domain and frequency domain, with each having a particular set of advantages and disadvantages, recommends 1 that techniques described in Annex 1 to this Recommendation should be considered when measuring UWB transmissions. * Radiocommunication Study Group 1 made editorial amendments to this Recommendation in the years 2018 and 2019 in accordance with Resolution ITU-R 1. -

Quantum Noise and Quantum Measurement

Quantum noise and quantum measurement Aashish A. Clerk Department of Physics, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3A 2T8 1 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Quantum noise spectral densities: some essential features 2 2.1 Classical noise basics 2 2.2 Quantum noise spectral densities 3 2.3 Brief example: current noise of a quantum point contact 9 2.4 Heisenberg inequality on detector quantum noise 10 3 Quantum limit on QND qubit detection 16 3.1 Measurement rate and dephasing rate 16 3.2 Efficiency ratio 18 3.3 Example: QPC detector 20 3.4 Significance of the quantum limit on QND qubit detection 23 3.5 QND quantum limit beyond linear response 23 4 Quantum limit on linear amplification: the op-amp mode 24 4.1 Weak continuous position detection 24 4.2 A possible correlation-based loophole? 26 4.3 Power gain 27 4.4 Simplifications for a detector with ideal quantum noise and large power gain 30 4.5 Derivation of the quantum limit 30 4.6 Noise temperature 33 4.7 Quantum limit on an \op-amp" style voltage amplifier 33 5 Quantum limit on a linear-amplifier: scattering mode 38 5.1 Caves-Haus formulation of the scattering-mode quantum limit 38 5.2 Bosonic Scattering Description of a Two-Port Amplifier 41 References 50 1 Introduction The fact that quantum mechanics can place restrictions on our ability to make measurements is something we all encounter in our first quantum mechanics class. One is typically presented with the example of the Heisenberg microscope (Heisenberg, 1930), where the position of a particle is measured by scattering light off it. -

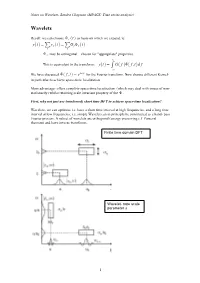

Wavelets T( )= T( ) G F( ) F ,T ( )D F

Notes on Wavelets- Sandra Chapman (MPAGS: Time series analysis) Wavelets Recall: we can choose ! f (t ) as basis on which we expand, ie: y(t ) = " y f (t ) = "G f ! f (t ) f f ! f may be orthogonal – chosen for "appropriate" properties. # This is equivalent to the transform: y(t ) = $ G( f )!( f ,t )d f "# We have discussed !( f ,t ) = e2!ift for the Fourier transform. Now choose different Kernel- in particular to achieve space-time localization. Main advantage- offers complete space-time localization (which may deal with issues of non- stationarity) whilst retaining scale invariant property of the ! . First, why not just use (windowed) short time DFT to achieve space-time localization? Wavelets- we can optimize i.e. have a short time interval at high frequencies, and a long time interval at low frequencies; i.e. simple Wavelet can in principle be constructed as a band- pass Fourier process. A subset of wavelets are orthogonal (energy preserving c.f Parseval theorem) and have inverse transforms. Finite time domain DFT Wavelet- note scale parameter s 1 Notes on Wavelets- Sandra Chapman (MPAGS: Time series analysis) So at its simplest, a wavelet transform is simply a collection of windowed band pass filters applied to the Fourier transform- and this is how wavelet transforms are often computed (as in Matlab). However we will want to impose some desirable properties, invertability (orthogonality) and completeness. Continuous Fourier transform: " m 1 T / 2 2!ifmt !2!ifmt x(t ) = Sme , fm = Sm = x(t )e dt # "!T / 2 m=!" T T ! i( n!m)x with orthogonality: e dx = 2!"mn "!! " x(t ) = # S( f )e2!ift df continuous Fourier transform pair: !" " S( f ) = # x(t )e!2!ift dt !" Continuous Wavelet transform: $ W !,a = x t " * t dt ( ) % ( ) ! ,a ( ) #$ 1 $ & $ ) da x(t) = ( W (!,a)"! ! ,a d! + 2 C % % a " 0 '#$ * 1 $ t # " ' Where the mother wavelet is ! " ,a (t) = ! & ) where ! is the shift parameter and a a % a ( is the scale (dilation) parameter (we can generalize to have a scaling function a(t)). -

The Power Spectral Density of Phase Noise and Jitter: Theory, Data Analysis, and Experimental Results by Gil Engel

AN-1067 APPLICATION NOTE One Technology Way • P. O. Box 9106 • Norwood, MA 02062-9106, U.S.A. • Tel: 781.329.4700 • Fax: 781.461.3113 • www.analog.com The Power Spectral Density of Phase Noise and Jitter: Theory, Data Analysis, and Experimental Results by Gil Engel INTRODUCTION GENERAL DESCRIPTION Jitter on analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog converter sam- There are numerous techniques for generating clocks used in pling clocks presents a limit to the maximum signal-to-noise electronic equipment. Circuits include R-C feedback circuits, ratio that can be achieved (see Integrated Analog-to-Digital and timers, oscillators, and crystals and crystal oscillators. Depend- Digital-to-Analog Converters by van de Plassche in the References ing on circuit requirements, less expensive sources with higher section). In this application note, phase noise and jitter are defined. phase noise (jitter) may be acceptable. However, recent devices The power spectral density of phase noise and jitter is developed, demand better clock performance and, consequently, more time domain and frequency domain measurement techniques costly clock sources. Similar demands are placed on the spectral are described, limitations of laboratory equipment are explained, purity of signals sampled by converters, especially frequency and correction factors to these techniques are provided. The synthesizers used as sources in the testing of current higher theory presented is supported with experimental results applied performance converters. In the following section, definitions to a real world problem. of phase noise and jitter are presented. Then a mathematical derivation is developed relating phase noise and jitter to their frequency representation. -

ETSI EN 302 500-1 V1.1.1 (2007-02) European Standard (Telecommunications Series)

ETSI EN 302 500-1 V1.1.1 (2007-02) European Standard (Telecommunications series) Electromagnetic compatibility and Radio spectrum Matters (ERM); Short Range Devices (SRD) using Ultra WideBand (UWB) technology; Location Tracking equipment operating in the frequency range from 6 GHz to 8,5 GHz; Part 1: Technical characteristics and test methods 2 ETSI EN 302 500-1 V1.1.1 (2007-02) Reference DEN/ERM-TG31C-004-1 Keywords radio, SRD, UWB, regulation, testing ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice Individual copies of the present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org The present document may be made available in more than one electronic version or in print. In any case of existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions, the reference version is the Portable Document Format (PDF). In case of dispute, the reference shall be the printing on ETSI printers of the PDF version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: http://portal.etsi.org/chaircor/ETSI_support.asp Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission. -

Fourier Transform, Parseval's Theoren, Autocorrelation and Spectral

ELG3175 Introduction to Communication Systems Fourier transform, Parseval’s theoren, Autocorrelation and Spectral Densities Fourier Transform of a Periodic Signal • A periodic signal can be expressed as a complex exponential Fourier series. • If x(t) is a periodic signal with period T, then : n ∞ j2π t T x(t) = ∑ X n e n=−∞ • Its Fourier Transform is given by: n n ∞ j2π t ∞ j2π t ∞ F T F T X ( f ) = ∑ X ne = ∑ X n e = ∑ X nδ ()f − nf o n=−∞ n=−∞ n=−∞ Lecture 4 Example x(t ) A … … 0.25 0.5 0.75 t -A ∞ 2A ∞ 2A x(t) = ∑ e j4πnt = ∑ − j e j4πnt n=−∞ jπn n=−∞ πn n isodd n isodd ∞ 2A X ( f ) = ∑ − j δ ()f − 2n n=−∞ πn n isodd Lecture 4 Example Continued |X(f)| 2A/π 2A/π 2A/3 π 2A/3 π 2A/5 π 2A/5 π -10 -6 -2 2 6 10 f Lecture 4 Energy of a periodic signal • If x(t) is periodic with period T, the energy on one period is: | ( |) 2 E p = ∫ x t dt T • The energy on N periods is EN = NE p. • The average normalized energy is E = lim NE p = ∞ N→∞ • Therefore periodic signals are never energy signals. Lecture 4 Average normalized power of periodic signals • The power of x(t) on one period is : 1 P = | x(t |) 2 dt p T ∫ T • And it’s power on N periods is : iT 1 1 N 1 1 P = | x(t |) 2 dt = | x(t |) 2 dt = × NP = P Np NT ∫ N ∑ T ∫ N p p NT i=1 (i− )1 T • It’s average normalized power is therefore P = lim PNp = Pp N →∞ • Therefore, for a periodic signal, its average normalized power is equal to the power over one period. -

Final Draft ETSI EN 302 288-1 V1.3.1 (2007-04) European Standard (Telecommunications Series)

Final draft ETSI EN 302 288-1 V1.3.1 (2007-04) European Standard (Telecommunications series) Electromagnetic compatibility and Radio spectrum Matters (ERM); Short Range Devices; Road Transport and Traffic Telematics (RTTT); Short range radar equipment operating in the 24 GHz range; Part 1: Technical requirements and methods of measurement 2 Final draft ETSI EN 302 288-1 V1.3.1 (2007-04) Reference REN/ERM-TG31B-004-1 Keywords radar, radio, RTTT, SRD, testing ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice Individual copies of the present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org The present document may be made available in more than one electronic version or in print. In any case of existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions, the reference version is the Portable Document Format (PDF). In case of dispute, the reference shall be the printing on ETSI printers of the PDF version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: http://portal.etsi.org/chaircor/ETSI_support.asp Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission. -

SPECTRAL PARAMETER ESTIMATION for LINEAR SYSTEM IDENTIFICATION, by C

I rtüii "inali*·'*!' ' *' EUR 4479 e i ■i$m\ SPECTRAL PARAMETI WÊà m ΐίίΒ-1« tum A.C. Ü léii**1 BE ii \>mm.m ' ä-'ÜBit-f , ,^. MWfj 1970 Blip Η ·■: Joint Nuclear Research Center Ispra Establishment - Italy Reactor Physics Department KesearcResearcnh KeacrorReactorss f tø pf IMI? Iiiiínílíi^'lliw^i»·*»!!!^ liillit, A A A K, f A this document was prepared under the sponsorship ot th of the European Communities^i.fttMä'iwi fiSt" «Hf Neither the Commission of the European Communities, its contractors nor ™ fiRá waëïiwmSm any person acting on their behalf : make any warranty or representation, express or implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of the information contained in this document, or that the use of 'any information, apparatus, method or process disclosed in this document may not infringe privately owned rights; or fWJftJSû llåf , „ u , , , , 1»Ü1 froassumm the ean usy e liabilitof anyy witinformationh respect, tapparatuso the use, methoof, ord foor r damageprocesss discloseresultindg in this document. fi Aie ιΐϋΐ •sír'5¿i'}ll! .¡vit• This report is on sale at the addresses listed on cover page 4 fS'-iEuflfi'piîMLsfli'iiÎMiW'1 'J*' r'Urt^íSlTSfltislHiilMiMHjTÍ"^ ut the price of FF 9,45 FB 85- DM 6,20 Lit 1.060 FI. 6,20 ïah When ordering, please quote the EUR number and the title, which are indicated on the cover of each report 1 WMpttIcU *v*r 1 BE sfliilìl »l^ifie KS? ί MM Printed by Smeets, Brussels LuxembourouTg, , May 1970 -h Vlililí u#feeItó1 ψ4 K*l*LrV,;íld This document was reproduced on the basis of the best available copy »Av tfwi< ¡;KLí W* EUR 4479 e SPECTRAL PARAMETER ESTIMATION FOR LINEAR SYSTEM IDENTIFICATION, by C. -

The Fundamentals of FFT-Based Signal Analysis and Measurement Michael Cerna and Audrey F

Application Note 041 The Fundamentals of FFT-Based Signal Analysis and Measurement Michael Cerna and Audrey F. Harvey Introduction The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and the power spectrum are powerful tools for analyzing and measuring signals from plug-in data acquisition (DAQ) devices. For example, you can effectively acquire time-domain signals, measure the frequency content, and convert the results to real-world units and displays as shown on traditional benchtop spectrum and network analyzers. By using plug-in DAQ devices, you can build a lower cost measurement system and avoid the communication overhead of working with a stand-alone instrument. Plus, you have the flexibility of configuring your measurement processing to meet your needs. To perform FFT-based measurement, however, you must understand the fundamental issues and computations involved. This application note serves the following purposes. • Describes some of the basic signal analysis computations, • Discusses antialiasing and acquisition front ends for FFT-based signal analysis, • Explains how to use windows correctly, • Explains some computations performed on the spectrum, and • Shows you how to use FFT-based functions for network measurement. The basic functions for FFT-based signal analysis are the FFT, the Power Spectrum, and the Cross Power Spectrum. Using these functions as building blocks, you can create additional measurement functions such as frequency response, impulse response, coherence, amplitude spectrum, and phase spectrum. FFTs and the Power Spectrum are useful for measuring the frequency content of stationary or transient signals. FFTs produce the average frequency content of a signal over the entire time that the signal was acquired. For this reason, you should use FFTs for stationary signal analysis or in cases where you need only the average energy at each frequency line. -

Spectral Analysis and Time Series

SSppeecctrtraall AAnnaallyyssiiss aanndd TTiimmee SSeerriieess Andreas Lagg Parrt II:: fundameentntaallss Parrt IIII: FourFourieerr sseerriiess Parrt IIIII: WWavvelettss on timme sseerriieess cllassiification definitionion why wavelet prob. densiity func. method transforms? auto-correlatilation properties fundamentals: FT, STFT and power spectral densiity convolutilution resolutionon prproblobleemmss cross-ccororrrelatiationn correlatiations multiresolution appliicationsons lleakage / wiindowiing analysiis: CWTT pre-processiing iirregular griid DWT samplinging noise removal trend removal EExxeercrcisiseess A.. Lagg ± Spectral Analylysisis BaBassiicc ddeessccrriippttiioonn ooff pphhyyssiiccaall ddaattaa determiinistic: descriibed by expliicciitt mmathemathematiaticalal rrelelatiationon k xt=X cos t t n nono determiinistic: no way to predict an exact value at a future instant of time n d e t e r m A.. Lagg ± Spectral Analylysisis ii n ii s t ii c CCllaassssiiffiiccaattiioonnss ooff ddeetteerrmmiinniissttiicc ddaattaa Determiinistic Perioiodic Nonperiiodicic Siinusoidaldal Complexex Periiodic Allmost perioiodic Transiient A.. Lagg ± Spectral Analylysisis SiSinnuussooiiddaall ddaattaa xt=X sin2 f 0 t T =1/ f 0 time history frequency spectrogrogram A.. Lagg ± Spectral Analylysisis CCoommpplleexx ppeerriiooddiicc ddaattaa xt=xt±nT n=1,2,3,... a xt = 0 a cos 2 n f t b sin 2 n f t 2 ∑ n 1 n 1 ((T = fundamental periiod) time history frequency spectrogrogram A.. Lagg ± Spectral Analylysisis AlAlmmoosstt ppeerriiooddiicc ddaattaa xt=X 1 sin2 t1 X 2 sin3t2 X 3 sin50 t3 no highest common diviisoror --> iinfinfininitelyy long periiodod TT time history frequency spectrogrogram A.. Lagg ± Spectral Analylysisis TrTraannssiieenntt nnoonn--ppeerriiooddiicc ddaattaa alll non-periiodic data other than almost periiodic data Ae−at t≥0 xt= { 0 t0 Ae−at cos bt t≥0 xt= { 0 t0 A c≥t≥0 xt= { 0 ct0 A. -

Spectral Density Estimation for Nonstationary Data with Nonzero Mean Function Anna E

Spectral density estimation for nonstationary data with nonzero mean function Anna E. Dudek, Lukasz Lenart To cite this version: Anna E. Dudek, Lukasz Lenart. Spectral density estimation for nonstationary data with nonzero mean function. 2021. hal-02442913v2 HAL Id: hal-02442913 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02442913v2 Preprint submitted on 1 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Spectral density estimation for nonstationary data with nonzero mean function Anna E. Dudek∗ Department of Applied Mathematics, AGH University of Science and Technology, al. Mickiewicza 30, 30-059 Krakow, Poland and Lukasz Lenart y Department of Mathematics, Cracow University of Economics, ul. Rakowicka 27, 31-510 Cracow, Poland March 1, 2021 Abstract We introduce a new approach for nonparametric spectral density estimation based on the subsampling technique, which we apply to the important class of nonstation- ary time series. These are almost periodically correlated sequences. In contrary to existing methods our technique does not require demeaning of the data. On the simulated data examples we compare our estimator of spectral density function with the classical one. Additionally, we propose a modified estimator, which allows to reduce the leakage effect. -

Chapter 8 Spectrum Analysis

CHAPTER 8 SPECTRUM ANALYSIS INTRODUCTION We have seen that the frequency response function T( j ) of a system characterizes the amplitude and phase of the output signal relative to that of the input signal for purely harmonic (sine or cosine) inputs. We also know from linear system theory that if the input to the system is a sum of sines and cosines, we can calculate the steady-state response of each sine and cosine separately and sum up the results to give the total response of the system. Hence if the input is: k 10 A0 x(t) Bk sin k t k (1) 2 k1 then the steady state output is: k 10 A0 y(t) T(j0) BT(jk k )sin k t k T(j k ) (2) 2 k1 Note that the constant term, a term of zero frequency, is found from multiplying the constant term in the input by the frequency response function evaluated at ω = 0 rad/s. So having a sum of sines and cosines representation of an input signal, we can easily predict the steady state response of the system to that input. The problem is how to put our signal in that sum of sines and cosines form. For a periodic signal, one that repeats exactly every, say, T seconds, there is a decomposition that we can use, called a Fourier Series decomposition, to put the signal in this form. If the signals are not periodic we can extend the Fourier Series approach and do another type of spectral decomposition of a signal called a Fourier Transform.