Islam at the Balkans in the Past, Today and in the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E-Mail: [email protected] Page: 1 Date: 08.08.2021 Https

E-mail: [email protected] Object name Subotička 24 Mirosavljeva 6 Humska 6 Dimitrija Tucovića 48 AVALA INVEST doo i HOME FOR Investor IVGOLD doo SUPERIOR GRADNJA doo SIGMA STAN doo YOU doo Readiness 05.2020 District ZVEZDARA ČUKARICA SAVSKI VENAC ZVEZDARA Micro district Cvetkova pijaca Banovo brdo Stadion Partizan Vukov spomenik Street Subotička 24 Mirosavljeva 6 Humska 6 Dimitrija Tucovića 48 Trolleybus № 19, 21, 22, 29 Trolleybus № Trolleybus № 40, 41 Trolleybus № Lines of public transport Tram № 5, 6, 7, 14 Tram № 12, 13 Tram № 9, 10, 14 Tram № Parking space Underground Underground Underground Underground and on-site Floors - - - - Heating Electrical - Heat pump Central, counter Conditioning - - Heat pump Conditioner installed Price from, €/sqm from 2 100 €/sqm from 2 000 €/sqm from 2 100 €/sqm On request Page: 1 Date: 28.08.2021 https://novazgrada.rs/en/mycomparison E-mail: [email protected] Object name TAURUNUM TANDEM Bulevar oslobođenja 159 Strumička 11 Stepa Nova Investor STORMS doo Privatni investitori BANAT GRADNJA doo TIM GRADNJA EXCLUSIVE doo Readiness 08.2019 10.2019 District ZEMUN VOŽDOVAC VOŽDOVAC VOŽDOVAC Micro district Gornji grad Voždovac Lekino brdo FON Street Cara Dušana 122 Bulevar oslobođenja 159 Strumička 11 Vojvode Stepe 250 Trolleybus № Trolleybus № Trolleybus № 22 Trolleybus № Lines of public transport Tram № Tram № 9, 10, 14 Tram № Tram № 9, 10, 14 Parking space Underground - Underground Underground Floors - - - - Heating Central, counter - Central, counter Heat pump Conditioning - - - Conditioner Price from, -

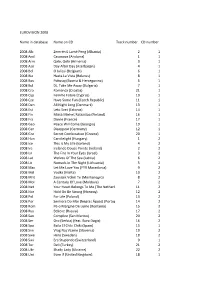

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

Eurovision Karaoke

1 Eurovision Karaoke ALBANÍA ASERBAÍDJAN ALB 06 Zjarr e ftohtë AZE 08 Day after day ALB 07 Hear My Plea AZE 09 Always ALB 10 It's All About You AZE 14 Start The Fire ALB 12 Suus AZE 15 Hour of the Wolf ALB 13 Identitet AZE 16 Miracle ALB 14 Hersi - One Night's Anger ALB 15 I’m Alive AUSTURRÍKI ALB 16 Fairytale AUT 89 Nur ein Lied ANDORRA AUT 90 Keine Mauern mehr AUT 04 Du bist AND 07 Salvem el món AUT 07 Get a life - get alive AUT 11 The Secret Is Love ARMENÍA AUT 12 Woki Mit Deim Popo AUT 13 Shine ARM 07 Anytime you need AUT 14 Conchita Wurst- Rise Like a Phoenix ARM 08 Qele Qele AUT 15 I Am Yours ARM 09 Nor Par (Jan Jan) AUT 16 Loin d’Ici ARM 10 Apricot Stone ARM 11 Boom Boom ÁSTRALÍA ARM 13 Lonely Planet AUS 15 Tonight Again ARM 14 Aram Mp3- Not Alone AUS 16 Sound of Silence ARM 15 Face the Shadow ARM 16 LoveWave 2 Eurovision Karaoke BELGÍA UKI 10 That Sounds Good To Me UKI 11 I Can BEL 86 J'aime la vie UKI 12 Love Will Set You Free BEL 87 Soldiers of love UKI 13 Believe in Me BEL 89 Door de wind UKI 14 Molly- Children of the Universe BEL 98 Dis oui UKI 15 Still in Love with You BEL 06 Je t'adore UKI 16 You’re Not Alone BEL 12 Would You? BEL 15 Rhythm Inside BÚLGARÍA BEL 16 What’s the Pressure BUL 05 Lorraine BOSNÍA OG HERSEGÓVÍNA BUL 07 Water BUL 12 Love Unlimited BOS 99 Putnici BUL 13 Samo Shampioni BOS 06 Lejla BUL 16 If Love Was a Crime BOS 07 Rijeka bez imena BOS 08 D Pokušaj DUET VERSION DANMÖRK BOS 08 S Pokušaj BOS 11 Love In Rewind DEN 97 Stemmen i mit liv BOS 12 Korake Ti Znam DEN 00 Fly on the wings of love BOS 16 Ljubav Je DEN 06 Twist of love DEN 07 Drama queen BRETLAND DEN 10 New Tomorrow DEN 12 Should've Known Better UKI 83 I'm never giving up DEN 13 Only Teardrops UKI 96 Ooh aah.. -

Eurovision Karaoke

1 Eurovision Karaoke Eurovision Karaoke 2 Eurovision Karaoke ALBANÍA AUS 14 Conchita Wurst- Rise Like a Phoenix ALB 07 Hear My Plea BELGÍA ALB 10 It's All About You BEL 06 Je t'adore ALB 12 Suus BEL 12 Would You? ALB 13 Identitet BEL 86 J'aime la vie ALB 14 Hersi - One Night's Anger BEL 87 Soldiers of love BEL 89 Door de wind BEL 98 Dis oui ARMENÍA ARM 07 Anytime you need BOSNÍA OG HERSEGÓVÍNA ARM 08 Qele Qele BOS 99 Putnici ARM 09 Nor Par (Jan Jan) BOS 06 Lejla ARM 10 Apricot Stone BOS 07 Rijeka bez imena ARM 11 Boom Boom ARM 13 Lonely Planet ARM 14 Aram Mp3- Not Alone BOS 11 Love In Rewind BOS 12 Korake Ti Znam ASERBAÍDSJAN AZE 08 Day after day BRETLAND AZE 09 Always UKI 83 I'm never giving up AZE 14 Start The Fire UKI 96 Ooh aah... just a little bit UKI 04 Hold onto our love AUSTURRÍKI UKI 07 Flying the flag (for you) AUS 89 Nur ein Lied UKI 10 That Sounds Good To Me AUS 90 Keine Mauern mehr UKI 11 I Can AUS 04 Du bist UKI 12 Love Will Set You Free AUS 07 Get a life - get alive UKI 13 Believe in Me AUS 11 The Secret Is Love UKI 14 Molly- Children of the Universe AUS 12 Woki Mit Deim Popo AUS 13 Shine 3 Eurovision Karaoke BÚLGARÍA FIN 13 Marry Me BUL 05 Lorraine FIN 84 Hengaillaan BUL 07 Water BUL 12 Love Unlimited FRAKKLAND BUL 13 Samo Shampioni FRA 69 Un jour, un enfant DANMÖRK FRA 93 Mama Corsica DEN 97 Stemmen i mit liv DEN 00 Fly on the wings of love FRA 03 Monts et merveilles DEN 06 Twist of love DEN 07 Drama queen DEN 10 New Tomorrow FRA 09 Et S'il Fallait Le Faire DEN 12 Should've Known Better FRA 11 Sognu DEN 13 Only Teardrops -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 150 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 23, 2004 No. 88 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was last day’s proceedings and announces served his parish and the Lancaster called to order by the Speaker pro tem- to the House his approval thereof. community during that time. He has pore (Mr. SHAW). Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- earned two master’s degrees and a doc- f nal stands approved. torate degree from the Concordia Theo- f logical Seminary located in Fort DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Wayne, Indiana, and St. Louis, Mis- PRO TEMPORE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE souri. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the In addition to his parish duties, Dr. fore the House the following commu- gentleman from Arkansas (Mr. ROSS) Davidson also serves as second vice nication from the Speaker: come forward and lead the House in the chairman of the Lutheran Church-Mis- WASHINGTON, DC, Pledge of Allegiance. souri Synod, where he provides gov- June 23, 2004. Mr. ROSS led the Pledge of Alle- erning assistance to 172 congregations I hereby appoint the Honorable E. CLAY giance as follows: located in Ohio and portions of West SHAW, Jr. to act as Speaker pro tempore on I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the Virginia and Kentucky. this day. United States of America, and to the Repub- Dr. Davidson is also known as a com- J. -

St. Jerome Commentary on Matthew

THE FATHERS OF THE CHURCH A NEW TRANSLATION VOLUME 117 THE FATHERS OF THE CHURCH A NEW TRANSLATION EDITORIAL BOARD Thomas P. Halton The Catholic University of America Editorial Director Elizabeth Clark Robert D. Sider Duke University Dickinson College Joseph T. Lienhard, S.J. Michael Slusser Fordham University Duquesne University David G. Hunter Cynthia White University of Kentucky The University of Arizona Kathleen McVey Rebecca Lyman Princeton Theological Seminary Church Divinity School of the Pacific David J. McGonagle Director The Catholic University of America Press FORMER EDITORIAL DIRECTORS Ludwig Schopp, Roy J. Deferrari, Bernard M. Peebles, Hermigild Dressler, O.F.M. Carole Monica C. Burnett Staff Editor ST. JEROME COMMENTARY ON MATTHEW Translated by THOMAS P. SCHECK Ave Maria University THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA PRESS Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2008 THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA PRESS All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standards for Information Science--Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI z39.48—1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jerome, Saint, d. 419 or 20. [Commentariorum in Evangelium Matthei libri quatuor. English] Commentary on Matthew / St. Jerome ; translated by Thomas P. Scheck. p. cm. -- (The fathers of the church ; v. 117) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 978-0-8132-0117-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Bible. N.T. Matthew-- Commentaries. I. Scheck, Thomas P., 1964– II. Title. BR65.J473C6413 2008 226.2'077--dc22 2008011349 Dedicated in friendship and affection to Father Ken Kuntz, Pastor of St. -

Preparatory Survey Report on the Sewerage System Improvement Project for the City of Belgrade in Republic of Serbia

REPUBLIC OF SERBIA THE CITY OF BELGRADE BELGRADE LAND DEVELOPMENT PUBLIC AGENCY (LDA) BELGRADE WATERWORKS AND SEWERAGE (BVK) PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE SEWERAGE SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT PROJECT FOR THE CITY OF BELGRADE IN REPUBLIC OF SERBIA VOLUME I SUMMARY & MAIN REPORT MAY 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY TEC INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. 7R CR(5) 13-018 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA THE CITY OF BELGRADE BELGRADE LAND DEVELOPMENT PUBLIC AGENCY (LDA) BELGRADE WATERWORKS AND SEWERAGE (BVK) PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE SEWERAGE SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT PROJECT FOR THE CITY OF BELGRADE IN REPUBLIC OF SERBIA VOLUME I SUMMARY & MAIN REPORT MAY 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY TEC INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. EXCHANGE RATE 1 Euro 115.00 Serbian Dinar 1 Euro 105.00 Japanese Yen as of January 2013 VOLUME I SUMMARY & MAIN REPORT VOLUME II APPENDIX-I VOLUME III APPENDIX-II (PRE EIA & LARAP) VOLUME IV DRAWINGS N Preparatory Survey on the Sewage System Improvement Project for the City of Belgrade Volume I Summary S1. Introduction (1) Background of the Survey The Republic of Serbia sets the first priority on joining the EU, hence securing the river water quality which meets the EU standards is absolutely imperative for this realization. The Government of Serbia formulated “National Physical Plan of the Republic of Serbia” and the City of Belgrade prepared a city master plan, “Master Plan of Belgrade to 2021” which was approved in September 2003 by the city council. Following the city master plan, Belgrade Waterworks and Sewerage prepared “Master Plan of the Belgrade Sewerage System to 2021” for its sewerage development. The Government of Serbia requested the Japanese Government to extend Japanese ODA Loans for a sewerage project, Sewerage System Improvement Project for the City of Belgrade (the Project), which is to implement a part of the said sewerage master plan. -

Bektashi Order - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Personal Tools Create Account Log In

Bektashi Order - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Personal tools Create account Log in Namespaces Views Article Read Bektashi OrderTalk Edit From Wikipedia, the freeVariants encyclopedia View history Main page More TheContents Bektashi Order (Turkish: Bektaşi Tarikatı), or the ideology of Bektashism (Turkish: Bektaşilik), is a dervish order (tariqat) named after the 13th century Persian[1][2][3][4] Order of Bektashi dervishes AleviFeatured Wali content (saint) Haji Bektash Veli, but founded by Balim Sultan.[5] The order is mainly found throughout Anatolia and the Balkans, and was particularly strong in Albania, Search BulgariaCurrent events, and among Ottoman-era Greek Muslims from the regions of Epirus, Crete and Greek Macedonia. However, the Bektashi order does not seem to have attracted quite as BektaşiSearch Tarikatı manyRandom adherents article from among Bosnian Muslims, who tended to favor more mainstream Sunni orders such as the Naqshbandiyya and Qadiriyya. InDonate addition to Wikipedia to the spiritual teachings of Haji Bektash Veli, the Bektashi order was later significantly influenced during its formative period by the Hurufis (in the early 15th century),Wikipedia storethe Qalandariyya stream of Sufism, and to varying degrees the Shia beliefs circulating in Anatolia during the 14th to 16th centuries. The mystical practices and rituals of theInteraction Bektashi order were systematized and structured by Balım Sultan in the 16th century after which many of the order's distinct practices and beliefs took shape. A largeHelp number of academics consider Bektashism to have fused a number of Shia and Sufi concepts, although the order contains rituals and doctrines that are distinct unto itself.About Throughout Wikipedia its history Bektashis have always had wide appeal and influence among both the Ottoman intellectual elite as well as the peasantry. -

Trees, Kings, and Politics: Studies in Assyrian Iconography

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2003 Trees, Kings, and Politics: Studies in Assyrian Iconography Porter, Barbara Nevling Abstract: The essays collected in this volume (two previously unpublished) examine ways in which the kings of ancient Assyria used visual images to shape political attitudes and behavior at the royal court, in the Assyrian homeland, and in Assyria’s vast and culturally diverse empire. The essays discuss visual images commissioned by Assyrian kings between the ninth and seventh century B.C., all carved in stone and publicly displayed - some on steles erected in provincial cities or in temples, some on the massive stone slabs lining the walls of Assyrian palaces and temples, and one on top of a stone bearing an inscription granting privileges to a recently conquered state. Although the essays examine a wide assortment of images, they develop a single hypothesis: that Neo-Assyrian kings saw visual images as powerful and effective tools of public persuasion, and that Assyrian carvings were often commissioned for much the same reason that modern politicians arrange ”photo opportunities” - to shape political opinion and behavior in diverse and not always cooperative populations by means of publicly displayed, politically charged visual images. Although there is increasing agreement among Assyriologists and art historians that Assyrian royal stone carvings were created and displayed at least in part for their political impact on contemporaries, there is still considerable debate about the effectiveness of visual imagery asa political tool, about the message each particular image was designed to convey, and about the audiences these images were meant to influence. -

Slu@Beni List Grada Beograda

ISSN 0350-4727 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 12 3 4 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– SLU@BENI LIST GRADA BEOGRADA Godina LII Broj 7 1. april 2008. godine Cena 180 dinara Na osnovu ~lana 15. stav 1. ta~ka 2. Zakona o lokalnim izborima („Slu`beni glasnik RS", broj 129/07), Gradska izborna komisija na 15. sednici odr`anoj 31. marta 2008. godine, donela je RE[EWE O ODRE\IVAWU BIRA^KIH MESTA NA TERITORIJI GRADA BEOGRADA ZA GLASAWE NA IZBORIMA 11. MAJA 2008. GODINE á Odre|uju se bira~ka mesta za glasawe na izborima za odbornike Skup{tine grada Beograda, koje je Odlukom raspisao predsednik Narodne skup{tine za 11. maj 2008. godine („Slu`beni glasnik RS", broj 130/07), u gradskim op{tinama na teritoriji grada Beograda, i to: ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Red. Naziv Adresa Podru~je koje obuhvata bira~ko mesto br. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 12 3 4 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– GRAD BEOGRAD 1. VO@DOVAC 1 Bawica Akcionarsko dru{tvo Bebelova 1-5, 2-6, Beranska 1, 5-17, 27a, 27v, 29a, 29b, 33-41a, "Dinara", Save Ma{kovi}a 3 2-58g, Bracana Bracanovi}a 3-15a, 2-12, Branka Gavele 1-11, 2, Bulevar oslobo|ewa 323-401b, 401e, 401i, 401k, 401n, Vidaka Markovi}a 3, 3a, 7, 11, 17, 2-6, 16, 16a, Vojvode Stepe 357-455a, 344-434, V. Popovi}a-Pineckog 3-17, 4-6a, Dobrivoja Isailovi}a 1-15, 2-16, Dr Izabele Haton 1-13, Joakima Rakovca 2-16, Kru`ni put vo`dova~ki 2-10, Mili}a Marinovi}a 1-39, 2-22, 30, Pazinska 1-53, Porodice Trajkovi} 1-21, 27, 43, 49, 2-44, 51j Porodice Trajkovi} 4 deo. -

For Buna/Bojana Area

Integrat ed Recources Management Plan (I RMP) for Buna/Bojana Area DRAFT (July 2015) 1 List of figures ................................................................................................................................. 5 List of tables .................................................................................................................................. 6 List of boxes .................................................................................................................................. 7 List of Images ................................................................................................................................ 7 Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 8 Context ................................................................................................................................ 10 The Integrated Plan Making Process ..................................................................................... 11 How to read the document .................................................................................................. 13 The Approach ...................................................................................................................... 13 PART A: THE PLAN................................................................................................................ 14 1. The foundations of the Plan - Establishing the process .................................................. -

Shipbreaking Bulletin of Information and Analysis on Ship Demolition # 57, from July 1, to September 30, 2019

Shipbreaking Bulletin of information and analysis on ship demolition # 57, from July 1, to September 30, 2019 November 27, 2019 Shipbreaking kills Shahidul Islam Mandal, 30, Rasel Matbor, 25, Nantu Hussain, 24, Chhobidul Haque, 30, Yousuf, 45, Aminul Islam, 50, Tushar Chakma, 27, Robiul Islam, 21, Masudul Islam, 22, Saiful Islam, 23. Bangladesh, Chattogram ex Chittagong Shipbreaking is a party In front of the Crystal Gold wreck, Parki Beach, Bangladesh (p 65). Content Bloody Summer 2 Ferry/passenger ship 23 Oil tanker 50 The Royal Navy anticipes Brexit 4 Livestock carrier 25 Chemical tanker 58 The Rio Tagus slow-speed death 5 Fishing ship 25 Gas tanker 60 Enlargement of the European list 7 General cargo carrier 26 Bulker 63 Europe-Africa: the on-going traffic 8 Container ship 37 Limestone carrier 71 Cameroon: 45 ships flying a flag of 9 Car carrier 43 Aggregate carrier 71 convenience or flying a pirate flag? Reefer 44 Cement 72 Trade Winds Ship Recycling Forum 18 Seismic research vessel 46 Dredger 72 - conclusion Drilling ship 46 Ro Ro 74 The wrecked ships did not survive 20 Offshore supply vessel 47 The END: Just Noran 75 3 rd quarter overview: the crash 21 Diving support vessel 51 Sources 78 Robin des Bois - 1 - Shipbreaking # 57 – November 2019 Bloody summer The summer of 2019 marked a respite for end-of-life ships. For shipbreaking workers it was bloody. Four European countries, Cyprus, France, Greece and the Netherlands, would deserve to be sued on different levels as shipowners, flag States or port States for having sold or let ships leave to substandard yards.