Southern Newspaper Publishers Association Foundation Southern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Independence Day: Resurgence

INDEPENDENCE DAY: RESURGENCE (2016) ● Rated PG 13 for sequences of sci fi action and destruction, and for some language ● $165,000,000 budget ● 2 hrs ● Directed by Roland Emmerich ● Produced by Lynn Harris, Matti Leshem, Douglas C. Merrifield ● The film was produced by Columbia Pictures, Sony Pictures QUICK THOUGHTS ● Phil Svitek ● Marisa Serafini ● Demetri Panos ● Sara Stretton DEVELOPMENT ● The possibility of a sequel to Independence Day had long been discussed, and the film's producer and writer, Dean Devlin, once stated that the world's reaction to the September 11 attacks influenced him to strongly consider making a sequel to the film ● Soon after the success of the first film, 20th Century Fox paid Dean Devlin a large sum of money to write a script for a sequel. However, after completing the script, Devlin didn't turn in the script and instead gave the money back to the studio, as he felt the story didn't live up to the first film. It was only approximately 15 years later, that Devlin met up with Roland Emmerich to try again, having felt that they had "cracked" a story for a sequel ● Devlin began writing an outline for a script with Emmerich, but in May 2004, Emmerich said he and Devlin had attempted to "figure out a way how to continue the story", but that this ultimately did not work, and the pair abandoned the idea ● In October 2009, Emmerich said he once again had plans for a sequel, and had since considered the idea of making two sequels to form a trilogy ● On June 24, 2011, Devlin confirmed that he and Emmerich had found an idea for the sequels and had written a treatment for it ● In October 2011, however, discussions for Will Smith returning were halted, due to Fox's refusal to provide the $50 million salary demanded by Smith for the two sequels ● Emmerich, however, made assurances that the films would be shot backtoback, regardless of Smith's involvement ○ Resurgence filmmakers were reported to be preparing versions of the film both with and without Will Smith. -

THE LANGUAGE FUNCTIONS USED by the MAIN CHARACTERS in WHITE HOUSE DOWN's FILM by RONALD EMMERICH THESIS Submitted to the Board

THE LANGUAGE FUNCTIONS USED BY THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN WHITE HOUSE DOWN’S FILM BY RONALD EMMERICH THESIS Submitted to the Board Examination In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For Literary Degree at English Literature Department by RIA KARMILA NIM: AI.150337 ENGLISH LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY THE STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SULTAN THAHA SAIFUDDIN JAMBI 2019 MOTTO You who have believed, fear Allah and speak words of appropriate justice. He will amend for you your deeds and forgive you your sins. And whoever obeys Allah and His Messenger has certainly attained a great attainment. Indeed, we offered the Trust to the heavens and the earth and the mountains, and they declined to bear it and feared it; but man [undertook to] bear it. Indeed, he was unjust and ignorant. (QS. Al- Ahzab: 70-72)1 Hai orang-orang yang beriman, bertakwalah kamu kepada Allah dan Katakanlah Perkataan yang benar, niscaya Allah memperbaiki bagimu amalan-amalanmu dan mengampuni bagimu dosa-dosamu. dan Barangsiapa mentaati Allah dan Rasul-Nya, Maka Sesungguhnya ia telah mendapat kemenangan yang besar. Sesungguhnya Kami telah mengemukakan amanat kepada langit, bumi dan gunung-gunung, Maka semuanya enggan untuk memikul amanat itu dan mereka khawatir akan mengkhianatinya, dan dipikullah amanat itu oleh manusia. Sesungguhnya manusia itu Amat zalim dan Amat bodoh. (QS. Al-Ahzab: 70-72)2 1 Sher, M. (2004). The Holy Qur’an, United Kingdem: Islam International Publications, p. 642. 2 Akhun, N. (2007). Al-Qur’an Terjemahan, Semarang: Thoa Putra, p. 543. DEDICATION First of all I would say the grateful to Allah SWT always gives me health to finish this thesis. -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

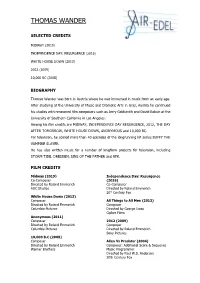

Thomas Wander

THOMAS WANDER SELECTED CREDITS MIDWAY (2019) INDEPENDENCE DAY: RESURGENCE (2016) WHITE HOUSE DOWN (2013) 2012 (2009) 10,000 BC (2008) BIOGRAPHY Thomas Wander was born in Austria where he was immersed in music from an early age. After studying at the University of Music and Dramatic Arts in Graz, Austria he continued his studies with renowned film composers such as Jerry Goldsmith and David Raksin at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Among his film credits are MIDWAY, INDEPENDENCE DAY RESURGENCE, 2012, THE DAY AFTER TOMORROW, WHITE HOUSE DOWN, ANONYMOUS and 10,000 BC. For television, he scored more than 40 episodes of the longrunning hit series BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER. He has also written music for a number of longform projects for television, including STORM TIDE, DRESDEN, SINS OF THE FATHER and RFK. FILM CREDITS Midway (2019) Independence Day: Resurgence Co-Composer (2016) Directed by Roland Emmerich Co-Composer AGC Studios Directed by Roland Emmerich 20th Century Fox White House Down (2013) Composer All Things to All Men (2013) Directed by Roland Emmerich Composer Columbia Pictures Directed by George Isaac Cipher Films Anonymous (2011) Composer 2012 (2009) Directed by Roland Emmerich Composer Columbia Pictures Directed by Roland Emmerich Sony Pictures 10,000 B.C (2008) Composer Alien Vs Predator (2004) Directed by Roland Emmerich Composer: Additional Score & Sequence Warner Brothers Music Programmer Directed by Paul W.S. Anderson 20th Century Fox The Day After Tomorrow (2004) Hostile Takeover (2001) Co-Composer Composer Directed by Roland Emmerich Directed by Carl Schenkel 20th Century Fox Columbia TriStar The Tunnel (2001) Marlene (2000) Composer Co-Composer Directed by Roland Suso Richter Directed by Joseph Vilsmaier SAT1/Teamworx Senator Film A Handful of Grass (2000) The Venice Project (1999) Composer Composer Directed by Roland Suso Richter Directed by Robert Dornhelm MTM Prod. -

Read the Full PDF

Chapter Title Preparing to Be President The Memos of Richard E. Neustadt Edited by Charles O. Jones The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute W A S H I N G T O N , D . C . 2000 Book Title 2 Chapter Title Contents Foreword vv Norman J. Ornstein and Thomas E. Mann Part 1 The Editor’s Introduction The Truman Aide Turned Professor 33 Part 2 Neustadt Memos for the Kennedy Transition Memo 1. Organizing the Transition 21 Memo 2. Staffing the President-Elect 38 Attachment A: Roosevelt’s Approach to Staffing the White House 54 Attachment B: Roosevelt’s Approach to Staffing the Budget Bureau 61 Memo 3. Cabinet Departments: Some Things to Keep in Mind 63 Memo 4. White House Titles 70 Memo 5. A White House Aide for Personnel and Congressional Liaison 72 Memo 6. The National Security Council: First Steps 75 Memo 7. Shutting Down Eisenhower’s “Cabinet System” 82 Memo 8. Appointing Fred Dutton “Staff Secretary” Instead of “Cabinet Secretary” 83 Memo 9. Location of Disarmament Agency 86 Memo 10. The Science Adviser: First Steps 94 iii iv CONTENTS Memo 11. Coping with “Flaps” in the Early Days of the New Administration 997 Memo 12. Possible Remarks by the President at the Outset of the Cabinet Meeting (prepared with Fred Dutton) 101 Part 3 Neustadt Memos from Reagan to Clinton Memo 13. Historical Problems in Staffing the White House (for James Baker III) 107 Memo 14. Transition Planning during the Campaign (for Michael Dukakis law partner Paul Brountas) 120 Memo 15. “Lessons” for the Eleven Weeks (for Bill Clinton friend Robert B. -

170210 Press Release Carl Laemmle Producers Award

Press Release The recipient of the Carl Laemmle Producers Award has been selected: Roland Emmerich chosen to receive this important new German award for producers Established by the German Producers Alliance – Film & Television in conjunction with the City of Laupheim, this year’s award honors the outstanding producer Roland Emmerich for his life’s work to date. The ceremony will be held on March 17, 2017. Berlin / Laupheim, February 10, 2017. Roland Emmerich is the first-ever winner of the new Carl Laemmle Producers Award, as announced by its originators, the Producers Alliance and the City of Laupheim, at a press conference today in Berlin. The outstanding producer Roland Emmerich is being honored with the Carl Laemmle Award in recognition of his life’s work to date. The award, which is named after the film pioneer and Hollywood trailblazer, is endowed with a prize of 40,000 euros. It will be presented on March 17, 2017 at a gala in Laupheim, Carl Laemmle’s Swabian birthplace. Hollywood giant Emmerich, who is likewise from Baden-Württemberg, will also receive a Laemmle sculpture in the form of a stylized lamb, created by the famous Staatliche Majolika Manufaktur in Karlsruhe. The first honoree has been chosen by an expert jury of nine, chaired by Martin Moszkowicz, head of Constantin Film and Page 1 board member of the Producers Alliance, who commented on the selection as follows: “What distinguishes a winner of the Carl Laemmle Award? Creativity, innovation, success, and the ability to boldly break new ground. All this can be said without hesitation of Roland Emmerich. -

Kabul Silo's, 2Nd Flour Mill Ready Soon

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Kabul Times Digitized Newspaper Archives 11-10-1968 Kabul Times (November 10, 1968, vol. 7, no. 192) Bakhtar News Agency Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bakhtar News Agency, "Kabul Times (November 10, 1968, vol. 7, no. 192)" (1968). Kabul Times. 1904. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes/1904 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Newspaper Archives at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kabul Times by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ,( ., 1 , ,. , ,. ,. .. ' • ·1 "! I, '. .. , .. \ .,. ~ , ., >' , ,. I' I ,-. .. ,. ., / \. .' , " , , . .; " I. , J 1 • ,. /" ' : . ': .' .. •., "~I '··WO~ER 9,·' 1968::·' PAGE' 4 ." I ; '· , . ;:~~ ,',,:, 'Middle·Jl;·p-~t ... .', ,..., ;- """ j" ":fl .. , • .EIiIB t. ,. loi;t'\"'~ ..... ,...••.. :.,~ 1. i( I.', of. i'" (, 'f'ltf~.\· ,I ').;, ',;t·f. -'. _~:,h'CO··h"l.:..t.l;..L~"'_':{ " .', It,: ,. '.,,.. •.,.... \ ~ ,.#\,1T\: "~~.~ ,I -,., ',,~ 'UTI ~~I;;"-" ,~;. ;), " ;pjai-1.amentlu'lW· '11 ES " to~~fll/ .'t:' ": ·lUf81· ,"-'011..\;:1· ...... " , . .~ f:'···'" iii·" ':\''1~~ ..,... ''t''(~ . :.'. ) " 'II t "I' ,W. ,l!,.•~!",,~~~'ii'P:;;' ~ '.""' t· .' ''''~ ., ,the,A:tiij.,aral1U..." 1< l. '. }.- ' .. 'c,hi1lliefo'f Vi~;(nr·'ii-• I I' > ·f ·0· . ,. TC:'-"·-'~_· '. .. .. 50 .~~ O. ~!l"":rt'.~g....-~..,,~, f ..... t. ;,'. velfallm, wu·tolcLllY·' '. , ':_. .... l,.,} } ...officl8ls :that" I In, ~iitlllJJ !~~: p'~~ , ,.:' livemhhig must be, dolild~~ -. ~ '.. !4BUL, SUNDAY, NOVEMBER· 10, 1968 (AQRAB 19, 1347S,H.) PRICE AF, 4 'lien!" ':!' a fallUre.:, in· .'::JAffliil'.'{;·: --"~-_Ii·_-_"_--;'----~IIIiI----Illi"'---=-"~II.,!! -"';~~:;;:'~~"-- 'w'". ,.1' '. .., ',f'1'\ t· .. " : \", ;! ml on~'r-"'" ~J,',., ,'. -

![Supplemental Information [PDF:402KB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4551/supplemental-information-pdf-402kb-3064551.webp)

Supplemental Information [PDF:402KB]

Entertainment Business Supplemental Information Fiscal year and three months ended March 31, 2014 May 14, 2014 Sony Corporation Pictures Segment 1 ■ Pictures Segment Aggregated U.S. Dollar Information 1 ■ Motion Pictures 1 - Motion Pictures Box Office for films released in North America - Select films to be released in the U.S. - Top DVD and Blu-rayTM titles released - DVD and Blu-rayTM titles to be released ■ Television Productions 3 - Television Series with an original broadcast on a U.S. network - Television Series with a new season to premiere on a U.S. network from April 1, 2014 onward - Select Television Series in U.S. off-network syndication - Television Series with an original broadcast on a non-U.S. network ■ Media Networks 5 - Television and Digital Channels Music Segment 7 ■ Recorded Music 7 - Top 10 best-selling recorded music releases - Upcoming releases ■ Music Publishing 8 - Number of songs in the music publishing catalog owned and administered as of March 31, 2014 Cautionary Statement Statements made in this supplemental information with respect to Sony’s current plans, estimates, strategies and beliefs and other statements that are not historical facts are forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, those statements using such words as “may,” “will,” “should,” “plan,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “estimate” and similar words, although some forward- looking statements are expressed differently. Sony cautions investors that a number of important risks and uncertainties could cause actual results to differ materially from those discussed in the forward-looking statements, and therefore investors should not place undue reliance on them. -

The Leader of the Free World? Frame, Gregory Politics And

The Leader of the Free World? ANGOR UNIVERSITY Frame, Gregory Politics and Politicians in Contemporary US Television PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 18/10/2016 Peer reviewed version Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Frame, G. (2016). The Leader of the Free World? Representing the declining presidency in television drama. In B. Kaklamanidou, & M. Tally (Eds.), Politics and Politicians in Contemporary US Television: Washington as fiction (pp. 61). (Routledge Advances in Television Studies). Routledge. Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 25. Sep. 2021 The Leader of the Free World? Representing the declining presidency in television drama By Gregory Frame This chapter represents a development of my research into the presidency in film and television, focusing primarily on the most recent examples of the institution’s representation in popular culture. -

George Mcgovern

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Contested Materials Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 34 9 7/8/1972Campaign Memo Author unknown. RE: North Carolina finance chairman. 1 pg. 34 9 7/5/1972Campaign Memo From Shumway to Strachan. RE: inexpensive travelling for campaign. 1 pg. 34 9 Campaign Memo Author unknown. RE: the appointment of Clark MacGregor as campaign director. 6 pgs. 34 9 7/10/1972Campaign Memo From Sedam to MacGregor. RE: Senator McGovern's campaign in a fourth party. 55 pgs. Tuesday, June 09, 2015 Page 1 of 12 Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 34 9 7/11/1972Campaign Memo From Joanou to Strachan. RE: campaign song status. 1 pg. 34 9 7/7/1972Campaign Memo From Dean to Haldeman. RE: potential disruptions at the Democratic National Convention. 2 pgs. 34 9 7/7/1972Campaign Memo From Strachan to Cole. RE: Neustadt-Meet the Press. 1 pg. 34 9 7/13/1972Campaign Newspaper Article, "McGovern vs. Nixon" by Norman Miller for the Wall Street Journal. 2 pgs. 34 9 6/27/1972Campaign Other Document Author unknown. RE: event activites. 1 pg. Tuesday, June 09, 2015 Page 2 of 12 Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 34 9 6/23/1972Campaign Memo From Magruder to Mitchell. RE: liaison between Hutar and political coordinators. 1 pg. 34 9 7/10/1972Campaign Memo Author unknown. RE: the Paulucci press conference. 7 pgs. 34 9 Campaign Memo Author unknown. -

Demand for Performance Goods: Import Quotas in the Chinese Movie Market

Demand for Performance Goods: Import Quotas in the Chinese Movie Market Chun-Yu Ho Marc Rysman Yanfei Wang University at Albany, SUNY Boston University Renmin University September 17, 2019 Abstract This paper develops and estimates a structural model of consumer demand for movies in which consumer preferences are heterogeneous over movie attributes and durable on movies that watched before. Consumers do not consider the movies watched in the past as relevant choices contemporarily, which leads consumers to be heterogeneous in their choice sets. Our main finding is that consumers prefer movies with time slots in holiday, and have heterogeneous preferences on watching movies. Interestingly, consumers prefer less to watch movies with a longer time gap from releasing week is driven by the unavailability of those movies in their choice set due to consumption durability. We employ our model to analyze the import liberalization for U.S. movies to China since 2012. Counterfactual experiments show that consumer welfare increases by 10% due to the import liberalization. However, the import liberalization reduces the market share of competing foreign movies, but raises that of domestic movies. Finally, if the consumption durability in preferences is ignored, we show that the welfare benefit for consumers is overestimated and the business stealing effects of extra foreign movies on competing foreign movies and domestic movies are also overestimated. Keywords: Demand Estimation, Choice Set, Trade Liberalization. JEL classifications: L10, L82, F13 1 1 Introduction Like many developing countries, China restricts the entry of cultural goods such as movies and books. We study the welfare implications of this restriction in the foreign film market from the perspective of consumer choice. -

'A BRAMBLE HOUSE CHRISTMAS' Cast Bios AUTUMN REESER (Willa

‘A BRAMBLE HOUSE CHRISTMAS’ Cast Bios AUTUMN REESER (Willa) – Autumn Reeser has established herself as a highly sought-after young actress in film and television. She can currently be seen on E!’s “The Arrangement” opposite Josh Henderson. She most recently starred in the independent film Valley of the Bones opposite Rhys Coiro, and Kill ‘em All opposite Jean-Claude Van Damme. Other recent feature credits include Clint Eastwood’s Sully and Dead Trigger. Reeser’s extensive television credits include starring roles in the action/drama “Last Resort” with Andre Braugher and Scott Speedman and in the superhero comedy/action/drama “No Ordinary Family” opposite Michael Chiklis and Julie Benz, both on ABC. She had a memorable turn as the ambitious junior agent Lizzie Grant on two seasons of the HBO hit “Entourage.” Reeser’s breakout role came on the FOX hit “The O.C.” Critics buzzed about her work in the series as the determined go-getter Taylor Townsend during its final two seasons. Other television credits include The CW’s “Valentine” and the ABC series “The Whispers” and “Nature of the Beast,” as well as guest roles on “Royal Pains,” “Jane by Design,” “Pushing Daisies,” “Ghost Whisperer,” “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia,” “Star Trek: Voyager,” “CSI,” and “Cold Case.” She has had memorable arcs on “Hawaii Five-0,” “Necessary Roughness,” “Human Target,” “Raising the Bar” and “George Lopez.” Reeser also had a recurring role on the comedy “Complete Savages,” working on episodes directed by Mel Gibson and Daniel Stern, among others. On the film side, Reeser appeared in So Undercover starring Miley Cyrus and was featured in Tony Krantz’s neo noir thriller The Big Bang, opposite Antonio Banderas.