The Leader of the Free World? Frame, Gregory Politics And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congress in the Mass Media: How the West Wing and Traditional Journalism Frame Congressional Power ______

CONGRESS IN THE MASS MEDIA: HOW THE WEST WING AND TRADITIONAL JOURNALISM FRAME CONGRESSIONAL POWER _______________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri – Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts _______________________________________________________ by CASSANDRA BELEK Dr. Lee Wilkins, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2010 1 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled CONGRESS IN THE MASS MEDIA: HOW THE WEST WING AND TRADITIONAL JOURNALISM FRAME CONGRESSIONAL POWER presented by Cassandra Belek, a candidate for the degree of master of journalism, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ____________________________________________________ Professor Lee Wilkins ____________________________________________________ Professor Jennifer Rowe ____________________________________________________ Professor Sandra Davidson ____________________________________________________ Professor Marvin Overby DEDICATION To everyone who has given me an education. To my parents, Joe and Katie, who sacrificed so much to ensure that my brother and I had the best educations possible. They taught me more than I can fit on this page. To my big brother Joey, who taught me about sports and ’90s rap music. To my Belek and Lankas extended families, who taught me where I come from and support me in where I am going. To all my teachers and professors—the good, the bad, and the awesome—at Holy Spirit Catholic School, St. Thomas Aquinas High School, the University of Notre Dame, and the University of Missouri. To Professor Christine Becker of the University of Notre Dame, who taught me it is okay to love television and whose mentorship continued even after I left the Dome. -

AUDIO BOOKS, MOVIES & MUSIC 3 Quarter 2013 Reinert-Alumni

AUDIO BOOKS, MOVIES & MUSIC 3rd Quarter 2013 Reinert-Alumni Library Audio Books Brown, Daniel, 1951- The boys in the boat : [nine Americans and their epic quest for gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics] / Daniel James Brown. This is the remarkable story of the University of Washington's 1936 eight-oar crew and their epic quest for an Olympic gold medal. The sons of loggers, shipyard workers, and farmers, the boys defeated elite rivals first from eastern and British universities and finally the German crew rowing for Adolf Hitler in the Olympic games in Berlin, 1936. GV791 .B844 2013AB Bradford, Barbara Taylor, 1933- Secrets from the past : a novel / Barbara Taylor Bradford. Moving from the hills above Nice to the canals and romance of Venice and the riot-filled streets of Libya, Secrets From The Past is a moving and emotional story of secrets, survival and love in its many guises. PS3552.R2147 S45 2013AB Deaver, Jeffery. The kill room / Jeffery Deaver. "It was a 'million-dollar bullet,' a sniper shot delivered from over a mile away. Its victim was no ordinary mark: he was a United States citizen, targeted by the United States government, and assassinated in the Bahamas. The nation's most renowned investigator and forensics expert, Lincoln Rhyme, is drafted to investigate. While his partner, Amelia Sachs, traces the victims steps in Manhattan, Rhyme leaves the city to pursue the sniper himself. As details of the case start to emerge, the pair discovers that not all is what it seems. When a deadly, knife-wielding assassin begins systematically eliminating all evidence-- including the witnesses-- Lincoln's investigation turns into a chilling battle of wits against a cold-blooded killer" -- containter. -

1.22: What Kind of Day Has It Been

The West Wing Weekly 1.22: What Kind of Day Has It Been [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’re listening the The West Wing Weekly, I’m Hrishikesh Hirway JOSH: ..and I’m Joshua Malina HRISHI: Today, we’re talking about the finale of season one JOSH: Woo! HRISHI: It’s episode 22, and it’s called ‘What kind of day has it been’. JOSH: It was written by Aaron Sorkin, it was directed by Tommy Schlamme, and it originally aired on May 17th, in the year 2000. HRISHI: Here’s a synopsis.. JOSH: A hrynopsis? HRISHI: [laughs] Sure.. JOSH: I just wanted to make sure because, you know, it’s an important distinction. HRISHI: An American fighter jet goes down in Iraq, and a rescue mission ensues to find the pilot. But, it’s a covert operation, so CJ has to mislead the press. Toby’s brother is onboard the space shuttle Columbia, but it’s having mechanical difficulties and can’t land. Plus, Josh has to meet with the Vice President to bring him around to the Bartlet administration's plans for campaign finance. President Bartlet travels to Rosalind, Virginia, to speak at the Newseum and give a live town hall meeting. But as they’re exiting, S#&* goes down and shots ring out. JOSH: Well done HRISHI: Before we even get into the episode though, Josh, I want to ask you about the title. ‘What kind of day has it been’ is a very Sorkin title, it’s been the finale for lots of things that he’s done before. -

Independence Day: Resurgence

INDEPENDENCE DAY: RESURGENCE (2016) ● Rated PG 13 for sequences of sci fi action and destruction, and for some language ● $165,000,000 budget ● 2 hrs ● Directed by Roland Emmerich ● Produced by Lynn Harris, Matti Leshem, Douglas C. Merrifield ● The film was produced by Columbia Pictures, Sony Pictures QUICK THOUGHTS ● Phil Svitek ● Marisa Serafini ● Demetri Panos ● Sara Stretton DEVELOPMENT ● The possibility of a sequel to Independence Day had long been discussed, and the film's producer and writer, Dean Devlin, once stated that the world's reaction to the September 11 attacks influenced him to strongly consider making a sequel to the film ● Soon after the success of the first film, 20th Century Fox paid Dean Devlin a large sum of money to write a script for a sequel. However, after completing the script, Devlin didn't turn in the script and instead gave the money back to the studio, as he felt the story didn't live up to the first film. It was only approximately 15 years later, that Devlin met up with Roland Emmerich to try again, having felt that they had "cracked" a story for a sequel ● Devlin began writing an outline for a script with Emmerich, but in May 2004, Emmerich said he and Devlin had attempted to "figure out a way how to continue the story", but that this ultimately did not work, and the pair abandoned the idea ● In October 2009, Emmerich said he once again had plans for a sequel, and had since considered the idea of making two sequels to form a trilogy ● On June 24, 2011, Devlin confirmed that he and Emmerich had found an idea for the sequels and had written a treatment for it ● In October 2011, however, discussions for Will Smith returning were halted, due to Fox's refusal to provide the $50 million salary demanded by Smith for the two sequels ● Emmerich, however, made assurances that the films would be shot backtoback, regardless of Smith's involvement ○ Resurgence filmmakers were reported to be preparing versions of the film both with and without Will Smith. -

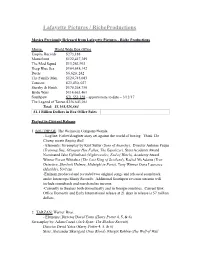

Riche Productions Current Slate

Lafayette Pictures / RicheProductions Movies Previously Released from Lafayette Pictures - Riche Productions Movie World Wide Box Office Empire Records $273,188 Mousehunt $122,417,389 The Mod Squad $13,263,993 Deep Blue Sea $164,648,142 Duets $6,620, 242 The Family Man $124,745,083 Tomcats $23,430, 027 Starsky & Hutch $170,268,750 Bride Wars $114,663,461 Southpaw $71,553,328 - approximate to date – 3/12/17 The Legend of Tarzan $356,643,061 Total: $1,168,526,664 $1.1 Billion Dollars in Box Office Sales Project in Current Release: 1. SOUTHPAW: The Weinstein Company/Wanda - Logline: Father/daughter story set against the world of boxing. Think The Champ meets Raging Bull. - Elements: Screenplay by Kurt Sutter (Sons of Anarchy). Director Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, Olympus Has Fallen, The Equalizer), Stars Academy Award Nominated Jake Gyllenhaal (Nightcrawler, End of Watch), Academy Award Winner Forest Whitaker (The Last King of Scotland), Rachel McAdams (True Detective, Sherlock Holmes, Midnight in Paris), Tony Winner Oona Laurence (Matilda), 50 Cent. -Eminem produced and recorded two original songs and released soundtrack under Interscope/Shady Records. Additional Southpaw revenue streams will include soundtrack and merchandise income. -Currently in theaters both domestically and in foreign countries. Current Box Office Domestic and Early International release at 21 days in release is 57 million dollars. 2. TARZAN: Warner Bros. - Elements: Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Screenplay by: Adam Cozad (Jack Ryan: The Shadow Recruit). Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Stars: Alexander Skarsgard (True Blood), Margot Robbie (The Wolf of Wall Street), Academy Award Nominated Samuel L. -

Attacco Al Potere 3 – Angel Has Fallen

LUCKY RED e UNIVERSAL PICTURES presentano GERARD BUTLER in ATTACCO AL POTERE 3 (ANGEL HAS FALLEN) un film di RIC ROMAN WAUGH con MORGAN FREEMAN NICK NOLTE Tutti i materiali stampa del film sono disponibili nella sezione press del sito www.luckyred.it DAL 28 AGOSTO AL CINEMA durata 114 minuti distribuito da UNIVERSAL PICTURES e LUCKY RED in associazione con 3 MARYS UFFICIO STAMPA FILM UFFICIO STAMPA LUCKY RED DIGITAL PR 404 MANZOPICCIRILLO Alessandra Tieri Chiara Bravo (+39) 347.0133173 (+39) 393.9328580 +39 335.8480787 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] - Georgette Ranucci www.manzopiccirillo.com +39 335.5943393 [email protected] Federica Perri +39 3280590564 [email protected] CAST ARTISTICO Mike Banning GERARD BUTLER Presidente Allan Trumbull MORGAN FREEMAN Clay Banning NICK NOLTE Wade Jennings DANNY HUSTON Agente FBI Helen Thompson JADA PINKETT SMITH David Gentry LANCE REDDICK Vicepresidente Kirby TIM BLAKE NELSON Leah Banning PIPER PERABO CAST TECNICO Regia RIC ROMAN WAUGH Sceneggiatura ROBERT MARK KAMEN E MATT COOK & RIC ROMAN WAUGH Soggetto CREIGHTON ROTHENBERGER & KATRIN BENEDIKT Direttore della fotografia JULES O’LOUGHLIN Scenografia RUSSELL DE ROZARIO Colonna sonora DAVID BUCKLEY Produttori GERARD BUTLER ALAN SIEGEL MATT O’TOOLE JOHN THOMPSON LES WELDON YARIV LERNER SINOSSI Dopo una vorticosa fuga, l’agente dei Servizi segreti Mike Banning (Gerard Butler) è ricercato dalla sua stessa agenzia e dall'FBI, mentre cerca di trovare i responsabili che minacciano la vita del Presidente degli Stati Uniti (Morgan Freeman). Nel disperato tentativo di scoprire la verità, Banning si rivolgerà a improbabili alleati per dimostrare la propria innocenza e per tenere la sua famiglia e l’intero Paese e fuori pericolo. -

THE LANGUAGE FUNCTIONS USED by the MAIN CHARACTERS in WHITE HOUSE DOWN's FILM by RONALD EMMERICH THESIS Submitted to the Board

THE LANGUAGE FUNCTIONS USED BY THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN WHITE HOUSE DOWN’S FILM BY RONALD EMMERICH THESIS Submitted to the Board Examination In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For Literary Degree at English Literature Department by RIA KARMILA NIM: AI.150337 ENGLISH LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY THE STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SULTAN THAHA SAIFUDDIN JAMBI 2019 MOTTO You who have believed, fear Allah and speak words of appropriate justice. He will amend for you your deeds and forgive you your sins. And whoever obeys Allah and His Messenger has certainly attained a great attainment. Indeed, we offered the Trust to the heavens and the earth and the mountains, and they declined to bear it and feared it; but man [undertook to] bear it. Indeed, he was unjust and ignorant. (QS. Al- Ahzab: 70-72)1 Hai orang-orang yang beriman, bertakwalah kamu kepada Allah dan Katakanlah Perkataan yang benar, niscaya Allah memperbaiki bagimu amalan-amalanmu dan mengampuni bagimu dosa-dosamu. dan Barangsiapa mentaati Allah dan Rasul-Nya, Maka Sesungguhnya ia telah mendapat kemenangan yang besar. Sesungguhnya Kami telah mengemukakan amanat kepada langit, bumi dan gunung-gunung, Maka semuanya enggan untuk memikul amanat itu dan mereka khawatir akan mengkhianatinya, dan dipikullah amanat itu oleh manusia. Sesungguhnya manusia itu Amat zalim dan Amat bodoh. (QS. Al-Ahzab: 70-72)2 1 Sher, M. (2004). The Holy Qur’an, United Kingdem: Islam International Publications, p. 642. 2 Akhun, N. (2007). Al-Qur’an Terjemahan, Semarang: Thoa Putra, p. 543. DEDICATION First of all I would say the grateful to Allah SWT always gives me health to finish this thesis. -

Friday, March 18

Movies starting Friday, March 18 www.marcomovies.com America’s Original First Run Food Theater! We recommend that you arrive 30 minutes before ShowTime. “The Divergent Series: Allegiant” Rated PG-13 Run Time 2:00 Starring Shailene Woodley and Theo James Start 2:30 5:40 8:45 End 4:30 7:40 10:45 Rated PG-13 for intense violence and action, thematic elements, and some partial nudity. “Zootopia” Rated PG Run Time 1:50 A Disney Animated Feature Film Start 2:50 5:50 8:45 End 4:40 7:40 10:35 Rated PG for some thematic elements, rude humor and action. “London Has Fallen” Rated R Run Time 1:45 Starring Gerard Butler and Morgan Freeman Start 3:00 6:00 8:45 End 4:45 7:45 10:30 Rated R for strong violence and language throughout. “The Lady In the Van” Rated PG-13 Run Time 1:45 Starring Maggie Smith and Alex Jennings Start 2:40 5:30 8:45 End 4:45 7:45 10:30 Rated PG-13 for a brief unsettling image ***Prices*** Matinees* $9.00 (3D $12.00) ~ Adults $12.00 (3D $15.00) Seniors and Children under 12 $9.50 (3D $12.50) Visit Marco Movies at www.marcomovies.com facebook.com/MarcoMovies The Divergent Series: Allegiant (PG-13) • Shailene Woodley • Theo James • After the earth-shattering revelations of Insurgent , Tris must escape with Four and go beyond the wall enclosing Chicago. For the first time ever, they will leave the only city and family they have ever known. -

THE WEST WING by ANINDITA BISWAS

UNWRAPPING THE WINGS OF THE TELEVISION SHOW: THE WEST WING By ANINDITA BISWAS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Communication December 2008 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Mary M. Dalton, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________ Examining Committee: Allan Louden, Ph.D., ____________________________________ Wanda Balzano, Ph.D., _____________________________________ Acknowledgments Whatever I have achieved till now has been possible with the efforts, guidance, and wisdom of all those who have filled my life with their presence and will continue to do so in all my future endeavors. Dr.Mary Dalton : My advisor, an excellent academician, and the best teacher I have had to date. Thank you for encouraging me when I was losing my intellectual thinking. Thanks you for those long afternoon conversations/thesis meetings in your office, which always made me, feel better. Last, but not the least, thank you for baking the most wonderful cookies I have had till now. I have no words to describe how much your encouragement and criticism has enriched my life in the last two years. Dr. Allan Louden: Thank you for helping me get rid of my I-am-scared-of-Dr.Louden feeling. I have enjoyed all the conversations we had, loved all the books you recommended me to read, and enjoyed my foray into political communication, all because of you! Dr. Wanda Balzano : Thanks for all the constructive criticism and guidance that you have provided throughout this project. Dr. Ananda Mitra and Swati Basu: Thanks for all the encouragement, support, and motivation that helped me pull through the last two years of my stay in this country. -

William Paley

WILLIAM PALEY Editor PROJECTS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS THE RESIDENT Season 1 Phillip Noyce Amy Holden James, Todd Harthan, Rob Corn & Various Directors Fuqua Films / 3 Arts / Fox ICE Pilot Antoine Fuqua Antoine Fuqua eOne / The Audience Network FUTURE WORLD James Franco Vince Jolivette / Rabbit Bandini Productions & Bruce Thierry Cheung COIN HEIST Emily Hagins Marshall Lewy / Netflix / Adaptive Studios ALONE Matthew Coppola Mark Kassen, Iliana Nikolic Like Minded Entertainment SIREN Jesse Peyronel Ludo Poppe, Meg Thomson Mauna Kea Films ADDITIONAL/ASSISTANT EDITOR DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS LIKE.SHARE.FOLLOW Glenn Gers Adam Hendricks / Blumhouse / HBO Additional Editor TOTEM Marcel Sarmiento John Lang / Blumhouse / HBO Additional Editor LOW RIDERS Ricardo de Montreuil Phil Dawe / Universal / Blumhouse Additional Editor THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN Antoine Fuqua Todd Black / MGM / Sony Additional Editor SOUTHPAW Antoine Fuqua Todd Black, Jason Blumenthal Additional Editor The Weinstein Company THE EQUALIZER Antoine Fuqua Jason Blumenthal, Todd Black 1st Assistant Editor Columbia Pictures SLEEPY HOLLOW Pilot Len Wiseman April Nocifora 1st Assistant Editor 20th Century Fox OLYMPUS HAS FALLEN Antoine Fuqua Millennium 1st Assistant Editor 21 & OVER Jon Lucas Relativity 1st Assistant Editor & Scott Moore TRANSFORMERS: DARK OF THE MOON Michael Bay Paramount Pictures 3rd Assistant Editor MONTE CARLO Tom Bezucha 20th Century Fox 1st Assistant Editor AVATAR James Cameron Jon Landau Assistant Visual Effects Editor 20th Century Fox THE FAMILY TREE Vivi Friedman Driving Lessons LLC 1st Assistant Editor STREET KINGS David Ayer Fox Searchlight 2nd Assistant Editor BREACH Billy Ray Universal Studios Assistant Editor . -

The West Wing

38/ Pere Antoni Pons The everydayness of power The West Wing If the effect is the same as what happens with me, after seeing any average-quality chapter of The West Wing (1999-2006) the reader-spectator will think he or she is witnessing an incontrovertible landmark in the latest phase of audiovisual narrative. After viewing one of the more dazzling, memorable episodes, he or she will not hesitate to believe that this is to behold one of the major, most perfect intellectual and artistic events of the early twenty-first century, comparable —not only in creative virtuosity but also in meaning, magnitude and scope— with Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, Shakespeare’s tragedies, Balzac’s The Human Comedy, or the complete recordings of Bob Dylan. Over the top? Even with more rotund words, it would be no exaggeration. Nowadays, nobody can ignore the fact that a colossal explosion in quality has happened over the last decade in the universe of American TV series. The old idea according to which the hapless professionals —scriptwriters, actors and directors— the ones who lack the luck or talent to carve out a niche in Hollywood or to triumph in the world of cinema, have to work in television has now been so thoroughly debunked that it even seems to have been turned on its head. Thanks to titles like The Sopranos, Capo 35 Ample front (Capo 35 Broad forehead), Miquel Barceló (2009). Ceramic, 22,5 x 19 x 25 cm 39 40/41 II The everydayness of power: The West Wing Pere Antoni Pons Lost, and The Wire, no one doubts any more that TV series can be as well filmed, as well written and as well acted as any masterpiece of the big screen. -

Southern Newspaper Publishers Association Foundation Southern

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 04E 388 UD 010 974 AUTHOR Lee, Eugene C.,Ed. TITLE School Desegregation; Retrospect and Prospect. Southern Newspaper Publishers Association Foundation Seminar Books, Number S. INSTITUTIrN Southern Newspaper Publishers Association, Atlanta, Ga. PUB DATE Jul 70 NO-CE 158p. AVAILABLE FBCM Southern Newspaper Publishers Association Foundation, Atlanta, Ga. 30305 ($2.00) EDES PRICE !DES Price my-$0.6F. HC-$5.5e DESCEIPTORS *Court Litigation, Courts, Educational Research, *Federal Government, Federal Legislation, Feder-1 Programs, 7ntegration Plans, *Journalism, *School Integration, *Seminars IDENTIFIERS Emory Univ?rsity, Southern Newspaper Publishers Association ABSTRACT During July of 197C, Emory University and the Southern NeNEi;aper Publishers Association Foundation sponsore-' a seminar on school desegregation for Southern journalisto. The intent was to give journalists the opportunity to increase rheir knJwledse 7,nd understanding of the complex events the write about. Toward this end, journalists were brought together with educators and practitioners in areas of their common concern. The proceedings of this seminar were put together in book form. The essays included cover subjects ranging trom the Nixon administration to desegregation in Atlanta, Georgia. The selections do reflect, however, the division of interest in the conference, which were; (1) the courts and the law; (2) politics and the federal administrat ion;(3) educational research in desegregation; and, (4) implementation of desegregation. (Author/JW) Cia U.S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDEICATIO. & WELFARE OF EDUCATION CO THIS DOCOFFICEUMiNT HAS GLEN REPRODULEO EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON DR re% ORGANU.ATION ORIGINATING IT POINIS OF VIL4 OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECES E) SARILY DEPRUSENT OFFICIA L OFFICE OF EUU CATION POSITION OR POLICY 4.