Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John G. Diefenbaker: the Political Apprenticeship Of

JOHN G. DIEFENBAKER: THE POLITICAL APPRENTICESHIP OF A SASKATCHEWAN POLITICIAN, 1925-1940 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon by Methodius R. Diakow March, 1995 @Copyright Methodius R. Diakow, 1995. All rights reserved. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department for the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or pUblication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 ii ABSTRACT John G. Diefenbaker is most often described by historians and biographers as a successful and popular politician. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE STORY BEHIND THE STORIES British and Dominion War Correspondents in the Western Theatres of the Second World War Brian P. D. Hannon Ph.D. Dissertation The University of Edinburgh School of History, Classics and Archaeology March 2015 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………… 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………… 6 The Media Environment ……………...……………….……………………….. 28 What Made a Correspondent? ……………...……………………………..……. 42 Supporting the Correspondent …………………………………….………........ 83 The Correspondent and Censorship …………………………………….…….. 121 Correspondent Techniques and Tools ………………………..………….......... 172 Correspondent Travel, Peril and Plunder ………………………………..……. 202 The Correspondents’ Stories ……………………………….………………..... 241 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………. 273 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………...... 281 Appendix …………………………………………...………………………… 300 3 ABSTRACT British and Dominion armed forces operations during the Second World War were followed closely by a journalistic army of correspondents employed by various media outlets including news agencies, newspapers and, for the first time on a large scale in a war, radio broadcasters. -

Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2017 Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War Sweazey, Connor Sweazey, C. (2017). Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/25173 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3759 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War by Connor Sweazey A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2017 © Connor Sweazey 2017 Abstract Public Canadian radio was at the height of its influence during the Second World War. Reacting to the medium’s growing significance, members of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) accepted that they had a wartime responsibility to maintain civilian morale. The CBC thus unequivocally supported the national cause throughout all levels of its organization. Its senior administrations and programmers directed the CBC’s efforts to aid the Canadian war effort. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada's Military, 1952-1992 by Mallory

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada’s Military, 19521992 by Mallory Schwartz Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Mallory Schwartz, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 ii Abstract War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada‘s Military, 19521992 Author: Mallory Schwartz Supervisor: Jeffrey A. Keshen From the earliest days of English-language Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television (CBC-TV), the military has been regularly featured on the news, public affairs, documentary, and drama programs. Little has been done to study these programs, despite calls for more research and many decades of work on the methods for the historical analysis of television. In addressing this gap, this thesis explores: how media representations of the military on CBC-TV (commemorative, history, public affairs and news programs) changed over time; what accounted for those changes; what they revealed about CBC-TV; and what they suggested about the way the military and its relationship with CBC-TV evolved. Through a material culture analysis of 245 programs/series about the Canadian military, veterans and defence issues that aired on CBC-TV over a 40-year period, beginning with its establishment in 1952, this thesis argues that the conditions surrounding each production were affected by a variety of factors, namely: (1) technology; (2) foreign broadcasters; (3) foreign sources of news; (4) the influence -

Chinese: Identity and the Internment of Missionary Nurses in China, 1941–1945

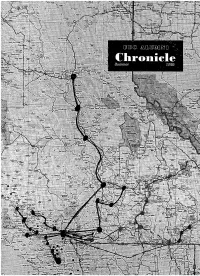

When We Were (almost) Chinese: Identity and the Internment of Missionary Nurses in China, 1941–1945 SONYA GRYPMA* Between 1923 and 1939, six China-born children of United Church of Canada North China missionaries returned to China as missionary nurses during one of the most inauspicious periods for China missions. Not only was the missionary enterprise under critical scrutiny, but China was also on the verge of war. Three of the nurses were interned by the Japanese in 1941. This study focuses on the pivotal decisions these nurses made to return to China and then to remain there after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, tracing the influences on those decisions back to their missionary childhoods in Henan. De 1923 a` 1939, six enfants ne´s en Chine de missionnaires que l’E´ glise Unie du Canada avait envoye´es en Chine du Nord sont retourne´es en Chine en tant qu’infir- mie`res missionnaires durant l’une des pe´riodes les plus inhospitalie`res pour des mis- sions en Chine. Non seulement scrutait-on l’action missionnaire a` la loupe, mais la guerre e´tait sur le point d’e´clater en Chine. Trois des infirmie`res ont e´te´ interne´es par les Japonais en 1941. Cette e´tude met l’accent sur la de´cision de´terminante que ces infirmie`res ont prise de retourner en Chine puis d’y rester apre`s l’e´clatement de la guerre sino-japonaise en 1937, retrac¸ant les motifs de cette de´cision jusqu’a` leur enfance missionnaire a` Henan. -

Articles by the New York Times On

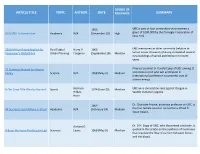

DEGREE OF ARTICLE TITLE TOPIC AUTHOR DATE RELEVANCE SUMMARY 1933 UBC is part of four universities that received a $200 000 To Universities Academia N/A (December 20) High grant of $200,000 by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. $200-Million Rebuilding Set for Real Estate/ Harry V. 1966 UBC mentioned as older university (relative to Vancouver's Waterfront Urban Planning Forgeron (September 18) Mention Simon Fraser University) having completed several new buildings of varied architecture in recent years. 21 Scientists Named for Atomic Physical scientist D. Harold Copp of UBC among 21 Parley Science N/A 1958 (May 3) Medium scientists named who will participate in international conference on peaceful uses of atomic energy. 8-Oar Crew Title Won by Harvard Sports Norman 1974 (June 23) Mention UBC wins consolation race against Oregon in Hildes- Seattle invitation regatta. Heim 1964 Dr. Charlotte Froese, associate professor at UBC, is 94 Scientists Get Millions in Grant Academia N/A (February 24) Medium the first female scientist named for a Alfred P. Sloan Award. Richard D. Dr. D.H. Copp of UBC, who discovered calcitonin, is A Bone Hormone Produced in Lab Sciences Lyons 1968 (May 9) Mention quoted in this article on the synthesis of hormones that regulate the flow of calcium between bones and the blood. A Curious Sugar Source Sciences N/A 1924 (June 26) High Professor John Davidson, botanist at UBC, carries out study showing that "Indians" had sugar before the arrival of white man. UBC alumnus (Bachelor’s Degree in History) Holger A Footnote: Kaiser's Plan to Richard H. -

Canadianism, Anglo-Canadian Identities and the Crisis of Britishness, 1964-1968

Nova Britannia Revisited: Canadianism, Anglo-Canadian Identities and the Crisis of Britishness, 1964-1968 C. P. Champion Department of History McGill University, Montreal A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History February 2007 © Christian Paul Champion, 2007 Table of Contents Dedication ……………………………….……….………………..………….…..2 Abstract / Résumé ………….……..……….……….…….…...……..………..….3 Acknowledgements……………………….….……………...………..….…..……5 Obiter Dicta….……………………………………….………..…..…..….……….6 Introduction …………………………………………….………..…...…..….….. 7 Chapter 1 Canadianism and Britishness in the Historiography..….…..………….33 Chapter 2 The Challenge of Anglo-Canadian ethnicity …..……..…….……….. 62 Chapter 3 Multiple Identities, Britishness, and Anglo-Canadianism ……….… 109 Chapter 4 Religion and War in Anglo-Canadian Identity Formation..…..……. 139 Chapter 5 The celebrated rite-de-passage at Oxford University …….…...…… 171 Chapter 6 The courtship and apprenticeship of non-Wasp ethnic groups….….. 202 Chapter 7 The “Canadian flag” debate of 1964-65………………………..…… 243 Chapter 8 Unification of the Canadian armed forces in 1966-68……..….……. 291 Conclusions: Diversity and continuity……..…………………………….…….. 335 Bibliography …………………………………………………………….………347 Index……………………………………………………………………………...384 1 For Helena-Maria, Crispin, and Philippa 2 Abstract The confrontation with Britishness in Canada in the mid-1960s is being revisited by scholars as a turning point in how the Canadian state was imagined and constructed. During what the present thesis calls the “crisis of Britishness” from 1964 to 1968, the British character of Canada was redefined and Britishness portrayed as something foreign or “other.” This post-British conception of Canada has been buttressed by historians depicting the British connection as a colonial hangover, an externally-derived, narrowly ethnic, nostalgic, or retardant force. However, Britishness, as a unique amalgam of hybrid identities in the Canadian context, in fact took on new and multiple meanings. -

AL CHRON 1963 2.Pdf

Businessmen at homeand abroad who read the :... want accurate interpretations of Canada's .. economic trendsread the B of XI Business B of M Business ..., , : .. Review. ...... ..,.:. .:.............. :.:.: ....... I Review '. I authoritativeIt'spuhlication, pro- an ..I I duced by Canada'sFirst Bank. Published I monthly,each issue containsadetailed I I survey of some aspect of the Canadian econ- I I I omy, or anover-all analysis of national I I I business trends, together with crisp reports I I I on each economic division of the country. I I I I I If you would like to read the B of hI's I I I Business Review regularly, simply fill in I I I andsend off thecoupon. No obligation. I I I Address I I I I I I "MYIO 3 MllllON BANK' CANADIANS I I I I I I I Business Development Division, I I Bunk of Montreal, I I I P.O. Box 6002, I BANKOF MONTREAL Montreul. P.Q., I I e4zuauhh 7rw ~cza4 I Canada. I I I I I CONTENTS Volume 17, No. 2- Summer, 1963 4 Ediforial -Paul S. Plan!, BA'49 Ediior 5 TheUniversity FrancesTucker, BA'50 13 CanadianUniversity Service Overseas Business Manager 14 AlumniAssociation Annual Meeting Gordon A. Thom, BCom'56, 16 Close-upon backing Mac MBA(Mary1and) 20 SimonFraser University "By Gordon M. Shrum, Editorial Commiiiee Chancellor of SimonFraser University Cecil Hacker, BA'33, chairman 22 LatinAmerica -Seminars a! InternationalHouse Inglis(Bill) Bell, BA'51, BLS(Tor.) 25 AlumniAssociation News Mrs. T. R. Boggs, BA'29 AllanFoiheringham, BA'54 26 TheCase now rests with !he Jury "T. -

Lester B. Pearson and the Peacekeeping Concept, 1930-55

National Library Biblioth&quenationale 1+1 ,,,da du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibtiographic Services se wices bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seU reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract Despite the considerable attention United Nations (UN) peacekeeping has received fiom scholars, the origins of it are still rnisunderstood. In Canada, the popular perception for over forty years bas been that Lester B. Pearson invented peacekeeping in 1956 during the Suez Cnsis. Contrary to this, peacekeeping existed even before the creation of the UN. Mile there is some suggestion that peacekeeping is an ancient concept, more recent and familiar exarnples exist. One notable precursor to UN peacekeeping was the League of Nations' Saarforce. The Saarforce was an international force mandated to help keep law and order in the Saar Territory during the plebiscite of 193 5 that was to decide if the inhabitants wanted to join with France, Germany, or remain under the League. -

A Case Study of the Canadian Missionary Dr. Richard Brown in China, 1938-19391

Ideology, Identity, and a New Role in World War Two: A Case Study of the Canadian Missionary Dr. Richard Brown in China, 1938-19391 SHENG-PING GUO Emmanuel College, University of Toronto Canadian churches began to send their organized, large-scale, and financially supported missionaries to China in the late 1880s.2 Even though that was later than most Western countries, from the peak time in 1920s to the great retreat in late 1940s the number of Canadian missionar- ies in China was ranked only next to the ones of America and British origins.3 The missionaries’ activities reached almost all of China. They accomplished some major projects, such as the creation of Christian universities, middle schools, hospitals, and churches.4 In missionary fields such as Taiwan, Henan, and Sichuan, the recognizable identity of Canada as a nation and the identities of denominational churches and famous missionaries gave the various Canadian missionary groups a role in influencing Canadian-Chinese relations.5 Before official diplomatic relations were established in 1942 between the Republic of China and Canada, missionaries were the main Canadian residential population in China and the main envoys among peoples and the two nations. Generally speaking, for a changing world system in the modern age of overseas expansion, missionaries played roles as “advance agents” of imperialism or the “brokers of a global cultural exchange” by contributing to the modernization process of host countries.6 Then “Christianization” became Western countries’ ideology and the motivation of their foreign policy-makers and missionaries for overseas expansion. Christian progressivism and pacifism, in some degree, stimulated Western soldiers, missionaries, diplomats, and traders in Historical Papers 2015: Canadian Society of Church History 6 A Case Study of the Canadian Missionary Dr. -

China's Politics of Modernization / by David Yuen Yeung.

CHINA'S POLITICS OF MODERNIZATION David Yuen Yeung B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1975 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Political Science David Yuen Yeung SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY AUGUST 1982 A11 rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name : David Yuen Yeung Degree : Master of Arts Title of Thesis: China's Politics of Modernization Examining Committee: Chairperson: Maureen Cove11 F. Qu&i/Quo, Senior Supervisor Ted Cohn KenY'? Okga, External Examiner ~ssodiateProfessor Department of Economics and Commerce Simon Fraser University PARTIAL COPY RIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for mu1 tiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesi s1Dissertation : e CXtnds /3dh oj- ~d~a*nl~efim Author : (signature) (name) (date) ABSTRACT This thesis is an attempt to examine the modernization efforts of the People's Republic of China under Mao and the post-Mao period.