Education, Technology, and the Social Construction of My Learning Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

Articles by the New York Times On

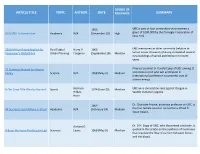

DEGREE OF ARTICLE TITLE TOPIC AUTHOR DATE RELEVANCE SUMMARY 1933 UBC is part of four universities that received a $200 000 To Universities Academia N/A (December 20) High grant of $200,000 by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. $200-Million Rebuilding Set for Real Estate/ Harry V. 1966 UBC mentioned as older university (relative to Vancouver's Waterfront Urban Planning Forgeron (September 18) Mention Simon Fraser University) having completed several new buildings of varied architecture in recent years. 21 Scientists Named for Atomic Physical scientist D. Harold Copp of UBC among 21 Parley Science N/A 1958 (May 3) Medium scientists named who will participate in international conference on peaceful uses of atomic energy. 8-Oar Crew Title Won by Harvard Sports Norman 1974 (June 23) Mention UBC wins consolation race against Oregon in Hildes- Seattle invitation regatta. Heim 1964 Dr. Charlotte Froese, associate professor at UBC, is 94 Scientists Get Millions in Grant Academia N/A (February 24) Medium the first female scientist named for a Alfred P. Sloan Award. Richard D. Dr. D.H. Copp of UBC, who discovered calcitonin, is A Bone Hormone Produced in Lab Sciences Lyons 1968 (May 9) Mention quoted in this article on the synthesis of hormones that regulate the flow of calcium between bones and the blood. A Curious Sugar Source Sciences N/A 1924 (June 26) High Professor John Davidson, botanist at UBC, carries out study showing that "Indians" had sugar before the arrival of white man. UBC alumnus (Bachelor’s Degree in History) Holger A Footnote: Kaiser's Plan to Richard H. -

AL CHRON 1963 2.Pdf

Businessmen at homeand abroad who read the :... want accurate interpretations of Canada's .. economic trendsread the B of XI Business B of M Business ..., , : .. Review. ...... ..,.:. .:.............. :.:.: ....... I Review '. I authoritativeIt'spuhlication, pro- an ..I I duced by Canada'sFirst Bank. Published I monthly,each issue containsadetailed I I survey of some aspect of the Canadian econ- I I I omy, or anover-all analysis of national I I I business trends, together with crisp reports I I I on each economic division of the country. I I I I I If you would like to read the B of hI's I I I Business Review regularly, simply fill in I I I andsend off thecoupon. No obligation. I I I Address I I I I I I "MYIO 3 MllllON BANK' CANADIANS I I I I I I I Business Development Division, I I Bunk of Montreal, I I I P.O. Box 6002, I BANKOF MONTREAL Montreul. P.Q., I I e4zuauhh 7rw ~cza4 I Canada. I I I I I CONTENTS Volume 17, No. 2- Summer, 1963 4 Ediforial -Paul S. Plan!, BA'49 Ediior 5 TheUniversity FrancesTucker, BA'50 13 CanadianUniversity Service Overseas Business Manager 14 AlumniAssociation Annual Meeting Gordon A. Thom, BCom'56, 16 Close-upon backing Mac MBA(Mary1and) 20 SimonFraser University "By Gordon M. Shrum, Editorial Commiiiee Chancellor of SimonFraser University Cecil Hacker, BA'33, chairman 22 LatinAmerica -Seminars a! InternationalHouse Inglis(Bill) Bell, BA'51, BLS(Tor.) 25 AlumniAssociation News Mrs. T. R. Boggs, BA'29 AllanFoiheringham, BA'54 26 TheCase now rests with !he Jury "T. -

Politics and Defence Research in the Cold War Jonathan Turner

Document generated on 09/24/2021 7:51 p.m. Scientia Canadensis Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine Revue canadienne d'histoire des sciences, des techniques et de la médecine Politics and Defence Research in the Cold War Jonathan Turner Science in Government Article abstract Volume 35, Number 1-2, 2012 The Defence Research Board (DRB) of Canada is an ideal case study for the operation and organization of science in government. The history of the DRB URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013980ar demonstrates the ebb and flow of government interest in science and defence DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1013980ar from 1947 to 1977. This paper traces defence research through its most transformative events: demobilization, the Korean War, the International See table of contents Geophysical Year, the Glassco Commission, the 1964 White Paper, integration and unification of the Department of National Defence, internal reviews, the 1971 White Paper, the Management Review Group, and the Lamontagne Committee. This sequence of transformative events reveals the importance of Publisher(s) politics and personalities to decision-making, and the difficult alliance of CSTHA/AHSTC scientists with soldiers. ISSN 0829-2507 (print) 1918-7750 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Turner, J. (2012). Politics and Defence Research in the Cold War. Scientia Canadensis, 35(1-2), 39–63. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013980ar Copyright © Canadian Science and Technology Historical Association / This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Association pour l'histoire de la science et de la technologie au Canada, 2012 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

Timeline Version

1 To: Members of the Department of Physics and Astronomy From: Ed Auld May 2, 2008 Here is a “Coffee room copy” of the latest timeline version. Please feel free to copy it, read it and get comments back to me. If you would like to get an electronic copy please email at [email protected] Where you see italics, means I want more information. I have received a great deal of good information from several people. That is the major difference between this version and previous ones. Happy reading, Timeline internal History Time-line for Physics and Astronomy (DRAFT 3) To be used by the Faculty of Science in preparing a document for the 100th anniversary celebration in 2008. E.G.Auld: May 2, 2008 1864: Henry Marshall Tory was born. He was the first president of the University of Alberta (1908-1928), the first president of the National Research Council(1928-1935) and the first president of Carleton College(1942-1947). In 1906, he helped establish the McGill University College of British Columbia absorbed into the University of British Columbia in 1915. His brother was James Cranswick Tory, Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia. He was a faculty member at McGill. He and Ernest Rutherford were close friends. 1908: Ernest Rutherford received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work in articulating the uranium, radium and thorium decay series and the associated discovery of the exponential law of the nature of alpha, beta and gamma radiation and of the existence of isotopes. Kammerlingh Onnes achieved the first successful liquifaction of Helium. -

The Defence Research Board of Canada, 1947 to 1977

The Defence Research Board of Canada, 1947 to 1977 by Jonathan Turner A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Jonathan Turner 2012 The Defence Research Board of Canada, 1947 to 1977 Jonathan Turner Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2012 Abstract The Defence Research Board of Canada existed from 1947 to 1977. It was created because of the successful contribution of scientific management and specific military technologies to victory in the Second World War, and it was dismantled during a period of review and renewal of the government’s science and defence policies. The demise of the Defence Research Board demonstrated the triumph of business and public administration models over scientific management in spite of the successful defence research program. Among the successful projects of the Defence Research Board were satellites, research rockets, hydrofoils, nylon pile clothing, the wind chill factor, the strategic distinction between first and second nuclear strikes, open heart surgery, and blast trials. The strengths of the Defence Research Board were the scientific management practices that united the four Chairmen (Omond Solandt, Hartley Zimmerman, Robert Uffen and Léon L’Heureux) and the bench scientists. Over the course of its existence the Defence Research Board was shaped by six chains of events. 1. Solandt’s ability to recruit veterans from 1947 to 1953, 2. The election of John Diefenbaker and the ensuing conflict between Diefenbaker and civil servants, particularly over nuclear weapons, which led to the Royal Commission on ii Government Organisation and a decade of review of national defence policy (including two White Papers, integration and unification, and the Management Review Group), 3. -

Simon Fraser University Archives and Records Management Department

Simon Fraser University Archives and Records Management Department Finding Aid - Learning and Instructional Development Centre fonds (F-18) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: November 09, 2018 Language of description: English Simon Fraser University Archives and Records Management Department Maggie Benston Student Services Building, Rm. 0400 8888 University Dr. Burnaby BC Canada V5A 1S6 Telephone: 778.782.2380 Email: [email protected] http://www.sfu.ca/archives http://atom.archives.sfu.ca/index.php/f-18 Learning and Instructional Development Centre fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Series -

Download This PDF File

FEATURE ARTICLE Destabilizing Curriculum History: A Genealogy of Critical Thinking ASHLEY PULLMAN Simon Fraser University In the specialized areas of erudition as in the disqualified, popular knowledge there lay the memory of hostile encounters which even up to this day have been confined to the margins of knowledge. […] Let us give the term genealogy to the union of erudite knowledge and local memories which allows us to establish a historical knowledge of struggles and to make use of this knowledge tactically today. (Foucault, 1980, p. 83). IMON FRASER UNIVERSITY (SFU) IN VANCOUVER, CANADA admits approximately S 7,500 new students annually; of these, over 1000 students enroll in a first-year philosophy course in critical thinking (Course section enrolment report, 2012). While this course is one of the largest within this institution, it is offered in one of the smallest departments. Importantly, Philosophy XX1, entitled Critical Thinking, is not considered an introduction-to-philosophy course; rather, it is intended to be disciplinary neutral, for students not necessarily pursing a philosophy degree. While standard course credit is granted for successful completion, the class is not given numerical merit, and has simply been designated XX1. As the Spring 2012 course outline reads, the subject of critical thinking within this course involves teaching the “fundamental aim of being a responsible thinker, consumer and citizen” and “the ability to efficiently and accurately distinguish truth claims from false ones.” Similarly, the Summer 2012 course outline explains Phil XX1 as “a practical course, a course in applied logic” that will help students become better readers, listeners, writers, and speakers through providing “tools” that are needed in order to pursue academic interests and goals, and “fulfill” the “capacity to be rational.” This mandate to make a student a critical thinker is linked closely to its legitimation within curriculum, and the institutional impetus to create critical students. -

FALL 2009 Trekthe Magazine of the University of British Columbia

Searching for Bigfoot | comBing the coSmoS Literati Party: Alumni achievement awardS 2009 25 The Magazine of The University of British Columbia TrekFALL 2009 ent #40063528 M gree a ations Mail C Canadian Publi Published by The u b C Alumni Asso C i at i o n genetic knots Trek25 table of contents Editor in ChiEF Christopher Petty, MFA’86 untangled MAnAging Editor Vanessa Clarke, BA Art dirECtor Keith Leinweber, BDes Contributors Michael Awmack, Ba’01, MET’09 5 Take note Adrienne Watt boArd oF dirECtors from here. ChAir Ian Robertson, BSc’86, BA’88, MA, MBA 12 Letters to the editor ViCE ChAir Miranda Lam, LLB’02 trEAsurEr Robin Elliott, BCom’65 MEMbErs-At-LArgE (07-10) 14 Combing the cosmos: Searching for Don Dalik, BCom, LLB’76 Dallas Leung, BCom’94 By Hilary Feldman, BSc’86 the origins of the universe MEMbErs-At-LArgE (08-11) Launched this spring, the Planck and Herschel research satellites are expected to revolutionize Brent Cameron, BA, MBA’06 Marsha Walden, BCom’80 modern astronomy. Ernest Yee, BA’83, MA’87 MEMbErs At LArgE ’09-‘12 Aderita Guerreiro, BA’77 17 Footprints and fables: Mark Mawhinney, BA’94 By Don Wells, BA’89 PAst ChAir (09-10) John green’s half-century hunt for Bigfoot Doug Robinson, BCom’71, LLB’72 Newspaper journalist, author, publisher, businessman, politician, competitive sailor, boat sEnior AdMinistrAtion rEP (09-10) Stephen Owen, MBA, LLB’72, LLM builder, husband, father, community service leader and sasquatch investigator. Meet John Green, Brian Sullivan, AB, MPH wearer of many hats. AMs rEP (09-10) Tom Dvorak ConVoCAtion sEnAtE rEP (09-10) 20 From hugs to hazing: a history of Student orientation Chris Gorman, BA’99, MBA’09 Young ALuMni rEP (08-09) Often a reflection of the times, student orientation has taken different forms at UBC over the Carmen Lee, BA’01 past century. -

Recent Publications Publications Récentes

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 11:56 Scientia Canadensis Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine Revue canadienne d'histoire des sciences, des techniques et de la médecine Recent Publications Publications Récentes Volume 12, numéro 1 (34), printemps–été–spring–summer 1988 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/800268ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/800268ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) CSTHA/AHSTC ISSN 0829-2507 (imprimé) 1918-7750 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce document (1988). Recent Publications. Scientia Canadensis, 12(1), 66–69. https://doi.org/10.7202/800268ar Copyright © Canadian Science and Technology Historical Association / Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des Association pour l'histoire de la science et de la technologie au Canada, 1988 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ 66 RECENT PUBLICATIONS RECENTES AERONAUTICS Murray Peden, Fall of an Arrow: The Birth and Death of Canada's Supersonic Jet Interceptor that was Years Ahead of its Time (Don Mills: Stoddart, 1987) AGRICULTURE T.H. Anstey, The Formation of the Experimental Farms,' Prairie Forum 11:2 (fall 1986), 185-94. -

Download Download

Book Reviews 77 emotional state. The historian's task is always to search out the truth, for truth is essential to history. When Graham speaks of "the horrifying history of a forgotten people," of marine agents co-authoring "a long, dark chapter in Canadian history, inflicting hardships few Canadians could even contemplate," with Ottawa guaranteeing keepers a "life on the mudsill of society," the reader could be forgiven for thinking that not since the antebellum South has slavery been so fashionable. The truth is that while lightkeepers' wages were low and social benefits were non-existent, their lot was certainly no better or worse than most workers in turn-of-the-century Canada. In 1889, The Royal Commission on the Relations of Capital and Labour reported widespread exploitation in the manufacturing industry. In par ticular, it noted inadequate protection from belts, pulleys, and steam engines; crowded and unhealthy conditions; widespread child labour; fre quent unemployment; lack of compensation for industrial accident vic tims; workers forced to eat at their work post; and lack of job security. By not placing the lightkeepers' struggle within the larger context of Canadian labour history, Graham leaves the impression that somehow these "exiles" on the shores of British Columbia were singled out for inhumane treatment. Having expressed my reservations about the book, I believe nonetheless that Donald Graham has achieved one of his stated purposes. He has made a strong case against automating the lights. I know the need to keep the lights staffed. I was raised on the west coast of Vancouver Island, and while at university I spent summers working at a number of lighthouses. -

The Honourable Iona Campagnolo Fonds Accession No

The Honourable Iona Campagnolo fonds Accession No. 2009.6 Fonds Description and File Level Inventory Northern British Columbia Archives & Special Collections The Honourable Iona Campagnolo, P.C., O.C., O.B.C. The Honourable Iona Campagnolo fonds [Accession #2009.6] Boxes #1-41 Fonds Description and File Level Inventory FONDS DESCRIPTION AND FILE LEVEL INVENTORY CONTENTS TITLE PAGE NO. Fonds Level Description………………… 3 Series Level Description………………… 11 File Level Inventory……………………… 16 Photograph Inventory……………….......... 159 List of Appendices……………………….. 210 Title Page Credit: Official portrait of Iona Campagnolo as Minister of State, Fitness and Amateur Sport, 1978-79 (photographer unknown), The Honourable Iona Campagnolo fonds, Accession No. 2009.6.1.256 Northern B.C. Archives & Special Collections, University of Northern British Columbia Page 2 of 238 The Honourable Iona Campagnolo fonds [Accession #2009.6] Boxes #1-41 Fonds Description and File Level Inventory FONDS LEVEL DESCRIPTION The Honourable Iona Campagnolo fonds. 1937-2007, predominant 1971-2007 4.7m of textual records and other material • 2 CD-Rs (computer disk) • 1 DVD (optical disk) • 1 - 16mm film • 1 audio cassette • 797 photographs Biographical Sketch : Iona Victoria Campagnolo (née Hardy) was born in Vancouver, B.C on October 18, 1932 to Rosamond and Kenneth Hardy. Soon thereafter, little Iona – still a babe in arms - and her family returned to Galiano Island to her family home. Along with her three siblings, John, Harold and Marion, she was raised to be proud of her family’s pioneering roots: their grandfather, Finlay Murcheson, settled on the Island in 1882. In 1940, the Hardy family moved up the coast to the North Pacific Cannery located on the Skeena River near Prince Rupert, where her father worked as Chief of Maintenance.