Redalyc.Gender in Translating Lesbianism in the Second

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masculinity in Yu Hua's Fiction from Modernism to Postmodernism

Masculinity in Yu Hua’s Fiction from Modernism to Postmodernism By: Qing Ye East Asian Studies Department McGill University Montreal, QC. Canada Submission Date: 07/2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Master of Arts Unpublished work © 2009 Qing Ye I Abstract The Tiananmen Incident in 1989 triggered the process during which Chinese society evolved from so-called ―high modernism‖ to vague ―postmodernism‖. The purpose of this thesis is to examine and evaluate the gender representation in Chinese male intellectuals‘ writing when they face the aforementioned social evolution. The exemplary writer from the band of Chinese male intellectuals I have chosen is Yu Hua, one of the most important and successful novelists in China today. Coincidently, his writing career, spanning from the mid-1980s until present, parallels the Chinese intellectuals‘ pursuit of modernism and their acceptance of postmodernism. In my thesis, I re-visit four of his works in different eras, including One Kind of Reality (1988), Classical Love (1988), To Live (1992), and Brothers (2005), to explore the social, psychological, and aesthetical elements that formulate/reformulate male identity, male power and male/female relation in his fictional world. Inspired by those fictional male characters who are violent, anxious or even effeminized in his novels, one can perceive male intellectuals‘ complex feelings towards current Chinese society and culture. It is believed that this study will contribute to the literary and cultural investigation of the third-world intellectuals. II Résumé Les événements de la Place Tiananmen en 1989 a déclenché le processus durant lequel la société chinoise a évolué d‘un soi-disant "haut modernisme" vers un vague "post-modernisme". -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Literary Production and Popular Culture Film Adaptations in China Since 1990

Cambridge Journal of China Studies 43 Literary Production and Popular Culture Film Adaptations in China since 1990 Yimiao ZHU Nanjing Normal University, China Email: [email protected] Abstract: Since their invention, films have developed hand-in-hand with literature and film adaptations of literature have constituted the most important means of exchange between the two mediums. Since 1990, Chinese society has been undergoing a period of complete political, economic and cultural transformation. Chinese literature and art have, similarly, experienced unavoidable changes. The market economy has brought with it popular culture and stipulated a popularisation trend in film adaptations. The pursuit of entertainment and the expression of people’s anxiety have become two important dimensions of this trend. Meanwhile, the tendency towards popularisation in film adaptations has become a hidden factor influencing the characteristic features of literature and art. While “visualization narration” has promoted innovation in literary style, it has also, at the same time, damaged it. Throughout this period, the interplay between film adaptation and literary works has had a significant guiding influence on their respective development. Key Words: Since 1990; Popular culture; Film adaptation; Literary works; Interplay Volume 12, No. 1 44 Since its invention, cinema has used “adaptation” to cooperate closely with literature, draw on the rich, accumulated literary tradition and make up for its own artistic deficiencies during early development. As films became increasingly dependent on their connection with the novel, and as this connection deepened, accelerating the maturity of cinematic art, by the time cinema had the strength to assert its independence from literature, the vibrant phase of booming popular culture and rampant consumerism had already begun. -

Order and Law in China

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by George Washington University Law School GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2020 Order and Law in China Donald C. Clarke George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Donald C., "Order and Law in China" (2020). GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works. 1506. https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications/1506 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORDER AND LAW IN CHINA Donald Clarke* Aug. 25, 2020 I. Introduction Does China have a legal system? The question might seem obtuse, even offensive. However one characterizes the institutions of the first thirty years of the People’s Republic, the near half- century of the post-Mao era1 has almost universally been called one of construction of China’s legal system.2 Certainly great changes have taken place in China’s public order and dispute resolution institutions. At the same time, however, other things have changed little or not at all. Most commentary focuses on the changes; this article, by contrast, will look at what has not changed—the important continuities that have persisted for over four decades. These continuities and other important features of China’s institutions of public order and dispute resolution suggest that legality is not the best paradigm for understanding them. -

Order and Law in China

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2020 Order and Law in China Donald C. Clarke George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Donald C., "Order and Law in China" (2020). GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works. 1506. https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications/1506 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORDER AND LAW IN CHINA Donald Clarke* Aug. 25, 2020 I. Introduction Does China have a legal system? The question might seem obtuse, even offensive. However one characterizes the institutions of the first thirty years of the People’s Republic, the near half- century of the post-Mao era1 has almost universally been called one of construction of China’s legal system.2 Certainly great changes have taken place in China’s public order and dispute resolution institutions. At the same time, however, other things have changed little or not at all. Most commentary focuses on the changes; this article, by contrast, will look at what has not changed—the important continuities that have persisted for over four decades. These continuities and other important features of China’s institutions of public order and dispute resolution suggest that legality is not the best paradigm for understanding them. -

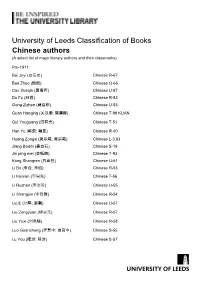

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese Authors (A Select List of Major Literary Authors and Their Classmarks)

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese authors (A select list of major literary authors and their classmarks) Pre-1911: Bai Juyi (白居易) Chinese R-67 Bao Zhao (鮑照) Chinese Q-66 Cao Xueqin (曹雪芹) Chinese U-87 Du Fu (杜甫) Chinese R-83 Gong Zizhen (龔自珍) Chinese U-53 Guan Hanqing (关汉卿; 關漢卿) Chinese T-99 KUAN Gui Youguang (归有光) Chinese T-51 Han Yu (韩愈; 韓愈) Chinese R-40 Huang Zongxi (黄宗羲; 黃宗羲) Chinese L-3.83 Jiang Baishi (姜白石) Chinese S-19 Jin ping mei (金瓶梅) Chinese T-93 Kong Shangren (孔尚任) Chinese U-51 Li Bo (李白; 李伯) Chinese R-53 Li Kaixian (李開先) Chinese T-56 Li Ruzhen (李汝珍) Chinese U-55 Li Shangyin (李商隱) Chinese R-54 Liu E (刘鹗; 劉鶚) Chinese U-57 Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元) Chinese R-57 Liu Yuxi (刘禹锡) Chinese R-58 Luo Guanzhong (罗贯中; 羅貫中) Chinese S-55 Lu You (陆游; 陸游) Chinese S-57 Ma Zhiyuan (马致远; 馬致遠) Chinese T-59 Meng Haoran (孟浩然) Chinese R-60 Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修; 歐陽修) Chinese S-64 Pu Songling (蒲松龄; 蒲松齡) Chinese U-70 Qu Yuan (屈原) Chinese Q-20 Ruan Ji (阮籍) Chinese Q-50 Shui hu zhuan (水浒传; 水滸傳) Chinese T-75 Su Manshu (苏曼殊; 蘇曼殊) Chinese U-99 SU Su Shi (苏轼; 蘇軾) Chinese S-78 Tang Xianzu (汤显祖; 湯顯祖) Chinese T-80 Tao Qian (陶潛) Chinese Q-81 Wang Anshi (王安石) Chinese S-89 Wang Shifu (王實甫) Chinese S-90 Wang Shizhen (王世貞) Chinese T-92 Wu Cheng’en (吳承恩) Chinese T-99 WU Wu Jingzi (吴敬梓; 吳敬梓) Chinese U-91 Wang Wei (王维; 王維) Chinese R-90 Ye Shi (叶适; 葉適) Chinese S-96 Yu Xin (庾信) Chinese Q-97 Yuan Mei (袁枚) Chinese U-96 Yuan Zhen (元稹) Chinese R-96 Zhang Juzheng (張居正) Chinese T-19 After 1911: [The catalogue should be used to verify classmarks in view of the on-going -

Film, Video, and Audio Sources

FILM, VIDEO, AND AUDIO SOURCES Anyang ying’er 安阳婴儿 (Orphan of Anyang). DVD. Dir. Wang Chao 王超. 2001. Beijing zazhong 北京杂种 (Beijing Bastards). VCD. Dir. Zhang Yuan 张元. 1993. Biena ziji budang ganbu 别拿自己不当干部 (A big potato). DVD. Dir. Feng Gong 冯巩. Tianjin Film Studio. 2007. Bushi naozhe wan de 不是闹着玩的 (No kidding). DVD. Dir. Lu Weiguo 卢卫国. Henan Film and Television Group and the Henan Film Studio. 2010 Chang hen ge 长恨歌 (Song of unending sorrow). DVD. Dir. Ding Hei 丁黑. Written by Wang Anyi 王安忆. Screenplay by Jiang Liping 蒋丽萍 and Zhao Yaomin 赵耀民. Wenhui xinmin lianhe baoye jituan; Shanghai dianying jituan gongsi, et al. 2006. Chen Xu VS huaping 陈旭 VS 花瓶 (Chen Xu VS vase). CD. Guangzhou: Feile Records, 2005. Dong shenme, biedong ganqing 动什么,别动感情 (Don’t mess with love). 20-episode telenovela. Dir. Tang Danian 唐大年. Written by Zhao Zhao 赵赵. Taihe yingshi touzi youxian gongsi. 2005. Dongchun de rizi 冬春的日子 (The days). DVD. Dir. Wang Xiaoshuai 王小帅. 1993. Douniu 斗牛 (Cow). Dir. Guan Hu 管虎. Changchun Film Studio. 2009. Ershou meigui 二手玫瑰 (Second hand rose). CD. Tianjin taida yinxiang faxing zhongxin. 2000. Fengkuang de saiche 疯狂的赛车 (Silver medalist). DVD. Dir. Ning Hao 宁浩. Beijing Film Studio and Warner China Film HG Corporation. 2009. Fengkuang de shitou 疯狂的石头 (Crazy stone). DVD. Dir. Ning Hao 宁浩. Hong Kong: Focus Films LTD. 2006. Gang de qin 钢的琴 (A piano in a factory). DVD. Dir. Zhang Meng 张猛. Liaoning Film Studio. 2011. Gaoxing 高兴 (Happiness). Dir. A Gan 阿甘. Beijing zongyi xinghao wenhua chuanbo gongsi and Shenzhen Golden Shore Film LTD. -

Alienation and the Motif of the Unlived Life in Liu Heng's Fiction

Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 Volume 2 Issue 2 Vol. 2.2 二卷二期 (1999) Article 5 1-1-1999 Alienation and the motif of the unlived life in Liu Heng's fiction Birgit LINDER University of Wisconsin, Madison Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/jmlc Recommended Citation Linder, B. (1999). Alienation and the motif of the unlived life in Liu Heng's fiction. Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese, 2(2), 119-148. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Humanities Research 人文學科研究中心 at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Alienation and the Motif of the Unlived Life in Liu Heng's Fiction Birgit Linder Sighing I said to myself: What have I done in this world? I was created to live, and I am dying without having lived. Jean-Jacques Rousseau Reveries of the Solitary Walker Critics have long argued that alienation is the essence of modern culture. Having long served as a theme in literature that profoundly reflects the changes and challenges of modernity, alienation has, after a hiatus of a few decades, undergone a conceptual resurgence during the 1990’s as recent research in the West indicates a correlation with the phenomenon of postmodernity.1 With the breakdown of communism in vast parts 1 Since alienation is a multi-disciplinary concept, a plethora of definitions is available. The most useful concepts for literary purposes are the definitions for “social alienation” and “self-alienation.” Ephraim H. -

Bibliography of Chinese Cinema Jerome Silbergeld, Wei Yang Princeton University, Department of Art and Archaeology

Chinese Cinema Bibliography 1 A Selected Bibliography of Chinese Cinema Jerome Silbergeld, Wei Yang Princeton University, Department of Art and Archaeology Note: This bibliography benefited from many published and online bibliographies of Chinese cinema, some of which are noted in the bibliography itself, as well as from correspondents who sent suggestions. We regret any errors. Please send further suggestions and corrections to the Tang Center for East Asian Art at [email protected]. The section on special themes is based on Princeton's course, Art 350, Chinese cinema. Version: August 10, 2004 Outline of this Bibliography General Studies Film Theory General, including Western Feminist Theory and Aesthetics in the Performance Arts Special Themes Film as History and History in Film Modernization: Hopes and Fears The Chinese Family Model Gender and Sexuality Youth , Ethnicity and Education The Politics of Form: Melodrama, Embodiment Cinema, Artistic Status, and the Sister Arts Chinese Cinema in a Global Era Defining "China" in a Global Culture: Hong Kong Taiwan Publications about Selected Individual Directors Chen Kaige Hou Hsiao-hsien Hu An (Ann Hui) Kwan, Stanley Lee Ang Tian Zhuangzhuang Tsai Mingliang Wong Kar-wai Xie Jin Yang, Edward (Yang Dechang) Zhang Yimou Zhang Yuan Film Review Indices Bibliographic References On-Line Film Resources Chinese Cinema Bibliography 2 General Studies Bao Minglian. Dongfang Haolaiwu: Zhongguo dianying shiye de jueqi yu fazhan 東方好萊塢:中國電影事業的崛起於發展. Shanghai: Shanghai renmin, 1991. Barlow, Tani and Donald Lowe. “Movies in China.” Jump Cut 31 (1986):55-57. Bazin, Andre. What is Cinema I and II. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967, 1971. Beach, Rex and Zhang Yingjin. -

International Law Teaching in China: Engaging in a Pedagogical Reform Or Embracing Professionalism and Internationalization?

Cambridge Journal of China Studies 11 International Law Teaching in China: Engaging in a Pedagogical Reform or Embracing Professionalism and Internationalization? Qingjiang KONG China University of Political Science and Law, China Email: [email protected] Abstract: As international law is becoming increasingly relevant to the rising China, serious problems have been found to cluster in the international law teaching in China. Since its introduction, the development of international law in China has been plagued by the love-and-hatred attitudes of the Chinese regimes in succession towards it. What Chinese law schools and beyond are lacking is a true professionalism that demands an estrangement from political reality and internationalization that calls for retrench of the pedagogical approaches. This article is intended to contribute to the understanding of the landscape of international law teaching in this rising country as it faces challenges. Key Words:China, International Law, International Law Teaching, Professionalism, Internationalization Professor of law, China University of Political Science and Law, and The Collaborative Innovation Centre for Territorial Sovereignty and Maritime Interests. Volume 12, No. 1 12 INTRODUCTION International law has shaped China’s perception of the world since its introduction into the Central Kingdom in the 1860s. Nowadays, international law is becoming increasingly relevant to the rising China. So is the teaching of international law. What Chinese law schools and beyond are lacking is among others, a precise overview of the development charts of the discipline of international law in China and the state of international law teaching in China. Problems about the teaching have clustered at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. -

Sabina Knight CV 2021

Sabina Knight 桑稟華 (earlier publications under Deirdre Sabina Knight) Program in World Literatures Pierce Hall 202, 21 West St., Northampton, MA 01063 [email protected], 413-585-3548, Twitter: @SabinaKnight1 / @SangBina https://www.smith.edu/academics/faculty/sabina-knight RESEARCH AREAS: contemporary Chinese fiction; comparative philosophy and literature; Chinese-English literary and cultural translation; early Chinese thought and poetry; TEACHING AREAS: Chinese literature, literature and medicine, Chinese-English creative writing and literary translation, comparative literature (Chinese, French, Russian, and American) DEGREES 1998 Ph.D., Chinese Literature (with Ph.D. minor in Comparative Literature), University of Wisconsin-Madison 1994 M.A., Chinese Literature, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1992 M.A., Comparative Literature, University of California, Berkeley 1988 B.A., Chinese, University of Wisconsin-Madison EDUCATION ABROAD 2005 Summer Literary Seminar, Herzen University, St. Petersburg, Russia 1995-1996 Graduate Institute of Chinese Literature, National Taiwan University 國立臺灣大學, 中國文學研究所, Taipei, Taiwan 1990 Blagovest Intensive Russian Language Program, Leningrad, former USSR 1988-1989 Department of Modern Letters, Université de Bourgogne, Dijon, France 1988 Centre International d’Études Françaises, Dijon, France 1986 UW Study Abroad in Taipei, Taiwan and Beijing Normal University 北师大, P.R.C. LANGUAGES: Chinese (Mandarin): near-native fluency Classical Chinese: excellent reading French: near-native fluency Russian: excellent reading, -

Neocolonialism in Translating China

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 20 (2018) Issue 7 Article 3 Neocolonialism in Translating China Guoqiang Qiao Shanghai International Studies Unviersity Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Qiao, Guoqiang. "Neocolonialism in Translating China." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 20.7 (2018): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.3327> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 175 times as of 11/ 07/19.