Neocolonialism in Translating China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masculinity in Yu Hua's Fiction from Modernism to Postmodernism

Masculinity in Yu Hua’s Fiction from Modernism to Postmodernism By: Qing Ye East Asian Studies Department McGill University Montreal, QC. Canada Submission Date: 07/2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Master of Arts Unpublished work © 2009 Qing Ye I Abstract The Tiananmen Incident in 1989 triggered the process during which Chinese society evolved from so-called ―high modernism‖ to vague ―postmodernism‖. The purpose of this thesis is to examine and evaluate the gender representation in Chinese male intellectuals‘ writing when they face the aforementioned social evolution. The exemplary writer from the band of Chinese male intellectuals I have chosen is Yu Hua, one of the most important and successful novelists in China today. Coincidently, his writing career, spanning from the mid-1980s until present, parallels the Chinese intellectuals‘ pursuit of modernism and their acceptance of postmodernism. In my thesis, I re-visit four of his works in different eras, including One Kind of Reality (1988), Classical Love (1988), To Live (1992), and Brothers (2005), to explore the social, psychological, and aesthetical elements that formulate/reformulate male identity, male power and male/female relation in his fictional world. Inspired by those fictional male characters who are violent, anxious or even effeminized in his novels, one can perceive male intellectuals‘ complex feelings towards current Chinese society and culture. It is believed that this study will contribute to the literary and cultural investigation of the third-world intellectuals. II Résumé Les événements de la Place Tiananmen en 1989 a déclenché le processus durant lequel la société chinoise a évolué d‘un soi-disant "haut modernisme" vers un vague "post-modernisme". -

The Role of Translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature : a Case Study of Howard Goldblatt's Translations of Mo Yan's Works

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Translation 3-9-2016 The role of translation in the Nobel Prize in literature : a case study of Howard Goldblatt's translations of Mo Yan's works Yau Wun YIM Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/tran_etd Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Yim, Y. W. (2016). The role of translation in the Nobel Prize in literature: A case study of Howard Goldblatt's translations of Mo Yan's works (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/tran_etd/16/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Translation at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. THE ROLE OF TRANSLATION IN THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE: A CASE STUDY OF HOWARD GOLDBLATT’S TRANSLATIONS OF MO YAN’S WORKS YIM YAU WUN MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 THE ROLE OF TRANSLATION IN THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE: A CASE STUDY OF HOWARD GOLDBLATT’S TRANSLATIONS OF MO YAN’S WORKS by YIM Yau Wun 嚴柔媛 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Translation LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 ABSTRACT The Role of Translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature: A Case Study of Howard Goldblatt’s Translations of Mo Yan’s Works by YIM Yau Wun Master of Philosophy The purpose of this thesis is to explore the role of the translator and translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature through an illustration of the case of Howard Goldblatt’s translations of Mo Yan’s works. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Rethinking Binarism in Translation Studies A Case Study of Translating the Chinese Nobel Laureates of Literature XIAO, DI How to cite: XIAO, DI (2017) Rethinking Binarism in Translation Studies A Case Study of Translating the Chinese Nobel Laureates of Literature, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12393/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 RETHINKING BINARISM IN TRANSLATION STUDIES A CASE STUDY OF TRANSLATING THE CHINESE NOBEL LAUREATES OF LITERATURE Submitted by Di Xiao School of Modern Languages and Cultures In partial fulfilment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Durham University 2017 DECLARATION The candidate confirms that the work is her own and that it has not been submitted, in whole or in part, in any previous application for a degree. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Literary Production and Popular Culture Film Adaptations in China Since 1990

Cambridge Journal of China Studies 43 Literary Production and Popular Culture Film Adaptations in China since 1990 Yimiao ZHU Nanjing Normal University, China Email: [email protected] Abstract: Since their invention, films have developed hand-in-hand with literature and film adaptations of literature have constituted the most important means of exchange between the two mediums. Since 1990, Chinese society has been undergoing a period of complete political, economic and cultural transformation. Chinese literature and art have, similarly, experienced unavoidable changes. The market economy has brought with it popular culture and stipulated a popularisation trend in film adaptations. The pursuit of entertainment and the expression of people’s anxiety have become two important dimensions of this trend. Meanwhile, the tendency towards popularisation in film adaptations has become a hidden factor influencing the characteristic features of literature and art. While “visualization narration” has promoted innovation in literary style, it has also, at the same time, damaged it. Throughout this period, the interplay between film adaptation and literary works has had a significant guiding influence on their respective development. Key Words: Since 1990; Popular culture; Film adaptation; Literary works; Interplay Volume 12, No. 1 44 Since its invention, cinema has used “adaptation” to cooperate closely with literature, draw on the rich, accumulated literary tradition and make up for its own artistic deficiencies during early development. As films became increasingly dependent on their connection with the novel, and as this connection deepened, accelerating the maturity of cinematic art, by the time cinema had the strength to assert its independence from literature, the vibrant phase of booming popular culture and rampant consumerism had already begun. -

Howard Goldblatt's Translations of Mo Yan's Works Into English

207 Howard Goldblatt’s Translations of Mo Yan’s Works into English: Reader Oriented Approach NISHIT KUMAR Abstract This article examines the strategies followed by Howard Goldblatt, the official translator of Mo Yan while translating his works from Chinese into English. Mo Yan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2012 and critics argued that it was Goldblatt’s translation that was mainly responsible for Mo Yan’s Nobel Prize in Literature. Though Mo Yan’s works in translation are available in various languages, it is Goldblatt’s version that has become most popular. Therefore, from the perspective of Translation Studies, it would be interesting to identify the techniques used by Goldblatt that make his translations so special. The present paper compares titles, structure, and culture-specific expressions in the original and its English translation to identify the strategies followed by Howard Goldblatt in translating Chinese literary texts. Keywords: Mo Yan, Howard Goldblatt, Chinese literature, Translation strategies. Introduction As an ancient civilization, China has rich literature spanning several millennia, touching upon a wide range of literary genres enriched by numerous creative writers. However, until the 1980s, modern Chinese literature was vastly under- represented within the purview of world literature and did not gain significant readership in other parts of the world. As a result, China has been seeking international recognition for its vast body of literature. The Chinese authors have been making an effort for the Nobel Prize in Literature from as far back as the 1940s. The failure and anxiety of not being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature led to an obsession in China, which DOI: 10.46623/tt/2021.15.1.no4 Translation Today, Volume 15, Issue 1 Nishit Kumar Lovell (2006: 2) has termed as ‘Nobel Complex.’ It is well- known that since its inception, it has been chiefly the authors writing in European languages who bagged the Nobel Prize in Literature. -

Mo Yan in Context: Nobel Laureate and Global Storyteller Angelica Duran Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 9-15-2014 Mo Yan in Context: Nobel Laureate and Global Storyteller Angelica Duran Purdue University Yuhan Huang Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Duran, Angelica, and Huang, Yuhan., Mo Yan in Context: Nobel Laureate and Global Storyteller. (2014). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Mo Yan in Context: Nobel Laureate and Global Storyteller Comparative Cultural Studies Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek, Series Editor The Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies publishes single-authored and thematic collected volumes of new scholarship. Manuscripts are invited for publication in the series in fields of the study of culture, literature, the arts, media studies, communication studies, the history of ideas, etc., and related disciplines of the humanities and social sciences to the series editor via e- mail at <[email protected]>. Comparative cultural studies is a contextual approach in the study of culture in a global and intercultural context and work with a plurality of methods and approaches; the theoretical and methodological framework of comparative cultural studies is built on tenets borrowed from the disciplines of cultural studies and comparative literature and from a range of thought including literary and culture theory, (radical) constructivism, communication theories, and systems theories; in comparative cultural studies focus is on theory and method as well as application. -

The Voice of the Translator: an Interview with Howard Goldblatt Jonathan Stalling Published Online: 07 Apr 2014

This article was downloaded by: [The University of Texas at Dallas] On: 25 May 2015, At: 12:53 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Translation Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/utrv20 The Voice of the Translator: An Interview with Howard Goldblatt Jonathan Stalling Published online: 07 Apr 2014. Click for updates To cite this article: Jonathan Stalling (2014) The Voice of the Translator: An Interview with Howard Goldblatt, Translation Review, 88:1, 1-12, DOI: 10.1080/07374836.2014.887808 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07374836.2014.887808 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Order and Law in China

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by George Washington University Law School GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2020 Order and Law in China Donald C. Clarke George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Donald C., "Order and Law in China" (2020). GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works. 1506. https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications/1506 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORDER AND LAW IN CHINA Donald Clarke* Aug. 25, 2020 I. Introduction Does China have a legal system? The question might seem obtuse, even offensive. However one characterizes the institutions of the first thirty years of the People’s Republic, the near half- century of the post-Mao era1 has almost universally been called one of construction of China’s legal system.2 Certainly great changes have taken place in China’s public order and dispute resolution institutions. At the same time, however, other things have changed little or not at all. Most commentary focuses on the changes; this article, by contrast, will look at what has not changed—the important continuities that have persisted for over four decades. These continuities and other important features of China’s institutions of public order and dispute resolution suggest that legality is not the best paradigm for understanding them. -

Order and Law in China

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2020 Order and Law in China Donald C. Clarke George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Donald C., "Order and Law in China" (2020). GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works. 1506. https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications/1506 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORDER AND LAW IN CHINA Donald Clarke* Aug. 25, 2020 I. Introduction Does China have a legal system? The question might seem obtuse, even offensive. However one characterizes the institutions of the first thirty years of the People’s Republic, the near half- century of the post-Mao era1 has almost universally been called one of construction of China’s legal system.2 Certainly great changes have taken place in China’s public order and dispute resolution institutions. At the same time, however, other things have changed little or not at all. Most commentary focuses on the changes; this article, by contrast, will look at what has not changed—the important continuities that have persisted for over four decades. These continuities and other important features of China’s institutions of public order and dispute resolution suggest that legality is not the best paradigm for understanding them. -

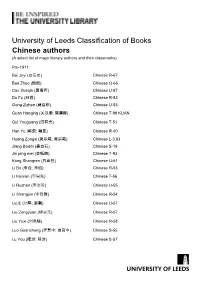

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese Authors (A Select List of Major Literary Authors and Their Classmarks)

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese authors (A select list of major literary authors and their classmarks) Pre-1911: Bai Juyi (白居易) Chinese R-67 Bao Zhao (鮑照) Chinese Q-66 Cao Xueqin (曹雪芹) Chinese U-87 Du Fu (杜甫) Chinese R-83 Gong Zizhen (龔自珍) Chinese U-53 Guan Hanqing (关汉卿; 關漢卿) Chinese T-99 KUAN Gui Youguang (归有光) Chinese T-51 Han Yu (韩愈; 韓愈) Chinese R-40 Huang Zongxi (黄宗羲; 黃宗羲) Chinese L-3.83 Jiang Baishi (姜白石) Chinese S-19 Jin ping mei (金瓶梅) Chinese T-93 Kong Shangren (孔尚任) Chinese U-51 Li Bo (李白; 李伯) Chinese R-53 Li Kaixian (李開先) Chinese T-56 Li Ruzhen (李汝珍) Chinese U-55 Li Shangyin (李商隱) Chinese R-54 Liu E (刘鹗; 劉鶚) Chinese U-57 Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元) Chinese R-57 Liu Yuxi (刘禹锡) Chinese R-58 Luo Guanzhong (罗贯中; 羅貫中) Chinese S-55 Lu You (陆游; 陸游) Chinese S-57 Ma Zhiyuan (马致远; 馬致遠) Chinese T-59 Meng Haoran (孟浩然) Chinese R-60 Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修; 歐陽修) Chinese S-64 Pu Songling (蒲松龄; 蒲松齡) Chinese U-70 Qu Yuan (屈原) Chinese Q-20 Ruan Ji (阮籍) Chinese Q-50 Shui hu zhuan (水浒传; 水滸傳) Chinese T-75 Su Manshu (苏曼殊; 蘇曼殊) Chinese U-99 SU Su Shi (苏轼; 蘇軾) Chinese S-78 Tang Xianzu (汤显祖; 湯顯祖) Chinese T-80 Tao Qian (陶潛) Chinese Q-81 Wang Anshi (王安石) Chinese S-89 Wang Shifu (王實甫) Chinese S-90 Wang Shizhen (王世貞) Chinese T-92 Wu Cheng’en (吳承恩) Chinese T-99 WU Wu Jingzi (吴敬梓; 吳敬梓) Chinese U-91 Wang Wei (王维; 王維) Chinese R-90 Ye Shi (叶适; 葉適) Chinese S-96 Yu Xin (庾信) Chinese Q-97 Yuan Mei (袁枚) Chinese U-96 Yuan Zhen (元稹) Chinese R-96 Zhang Juzheng (張居正) Chinese T-19 After 1911: [The catalogue should be used to verify classmarks in view of the on-going -

Zhang Kou in the Garlic Ballads Yiran Yang

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 Studying the Voice of Mo Yan and Howard Goldblatt: Zhang Kou in the Garlic Ballads Yiran Yang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Yang, Y.(2019). Studying the Voice of Mo Yan and Howard Goldblatt: Zhang Kou in the Garlic Ballads. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5316 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDYING THE VOICE OF MO YAN AND HOWARD GOLDBLATT: ZHANG KOU IN THE GARLIC BALLADS by Yiran Yang Bachelor of Arts Shandong University, 2014 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Jie Guo, Director of Thesis Michael G. Hill, Reader Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Yiran Yang, 2019 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my family. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my appreciation to faculty and staff who helped me along the way. My thesis advisor Dr. Guo Jie kept inspiring me. She made me realize the value of this project. This thesis would not come into being without her generous help. Dr. Michael Gibbs Hill has been kindly helping me since my first day at the USC Columbia.