Labels Are Not Characters: Critical Misperception of Falsettoland Jeffrey Smart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Specia[ O/A[Entines T£Dition Rrp Nrwn "When the Moon Hits Your Eye Like a Big Pizza Pie, That's Amok "

Specia[ o/a[entines t£dition rrp Nrwn "When the moon hits your eye like a big pizza pie, that's amok " THE WEEKLY NEWSPAPER OF ST. LOUIS U. HIGH Volume LVIII Monday, February 14, 1994 Number22V SLUHman To Latin 100 students: To Miss Catherine McHale of Blackrock, You were my prince, my dream. Salvete, discipuli! County Cork, winner of the Nat'l "King I waited so long Numquam dediscere: Dicite "Salve, mea Lear Essay Contest," and grace of the And was finally your princess. calumba" blackboard in Irish Lit Room #210, It was my fairy-tale. Pulchrae puellaeetpuella tibi dicet: "Amo My mistress's eyes are nothing like Too bad it was only make-believe. te, fortis vir!" the sun, especially when compared to You told me you loved me, Excorde, thee. and then walked out the door. Magistra To Ireland I wish to go, and would do Fairy tales always so just to ta1,k with you for a little, for not End happily ever after. T.J.C.- only are you most-beautiful but you are a Why can't mine? Thcre is not enough room in this fan of that most wonderfully bleak King Pretty Woman paper to tell you how I feel so I'll write Lear. another bad poem: And though the Atlantic Ocean keeps ToShauna: us separated (as well as money for the trip Though our minds only touched for The power and the gifts and the fact that we've never met-but one instant, I was captivated by your husky you seem to always bestow that'satriflehere)I'm asking you lhisday voice and yourincredible command ofthe keeps me ever so sane to be my Valentine. -

Crittendon Et Al V. International Follies, Inc. Et Al

Case 1:18-cv-02185-ELR Document 1 Filed 05/16/18 Page 1 of 32 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA ATLANTA DIVISION CRYSTAL CRITTENDON, ) SHALEAH DAYE, RIANA EAST, ) CASSIDY GATES, JOVANA ) CIVIL ACTION GIBBS-ARNOLD, ASHLEY ) FILE NO. 1:18-mi-99999 HAYES, MERRIAH ) HILLARD, ASHLEY JOHNSON, ) TIFFANY LOWE, JASMINE ROSS, ) JASMINE THOMAS, MEGAN ) THOMAS, and SAMANTHA ) WILLIAMS, individually and on ) FLSA COLLECTIVE ACTION behalf of those similarly situated ) and LINDSEY CROOME, NICOLE ) MILLER-JORDAN and AVIA ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED SHLTON individually only, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) INTERNATIONAL FOLLIES, INC. ) d/b/a Cheetah and JACK BRAGLIA, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT COME NOW, CRYSTAL CRITTENDON, SHALEAH DAYE, RIANA EAST, CASSIDY GATES, JOVANA GIBBS-ARNOLD, ASHLEY HAYES, MERRIAH HILLARD, ASHLEY JOHNSON, TIFFANY LOWE, -1- Case 1:18-cv-02185-ELR Document 1 Filed 05/16/18 Page 2 of 32 JASMINE ROSS, JASMINE THOMAS, MEGAN THOMAS, SAM WILLIAMS, Individually and on behalf of those similarly situated, and LINDSEY CROOME, NICOLE MILLER-JORDAN and AVIA SHELTON, individually and files their Complaint against INTERNATIONAL FOLLIES, INC. d/b/a Cheetah and JACK BRAGLIA and show: INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs are former or current employees of INTERNATIONAL FOLLIES, INC. (“Cheetah”). 2. Cheetah operates an adult entertainment club in Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia known as the “Cheetah.” 3. JACK BRAGLIA (“Braglia”) is the general manager of Cheetah and part owner of Cheetah. 4. Cheetah failed to pay Plaintiffs and other similarly situated entertainers the minimum wage and overtime wage for all hours worked in violation of 29 U.S.C. §§ 206 and 207 of the Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. -

Clark Spring Semester 2020 Homeschoole MT

Clark Spring Semester 2020 Homeschoole MT JENNA: In the early 1940s, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein III’s ‘Oklahoma!,’ adapted from a play written by Claremore playwright Lynn Riggs, opened on Broadway. It was the first musical they wrote together.. KYLE: Each had already found success on Broadway: Rodgers, having written a series of popular musicals with lyricist Lorenz Hart, and Hammerstein, having written the monumental classic, ‘Show Boat.’ But together with ‘Oklahoma!', they would change musical theatre forever. “Oh! What a Beautiful Mornin’” There's a bright golden haze on the meadow There's a bright golden haze on the meadow The corn is as high as an elephant's eye And it looks like it's climbing clear up to the sky Oh, what a beautiful mornin' Oh, what a beautiful day I've got a beautiful feeling Everything's going my way All the cattle are standing like statues All the cattle are standing like statues They don't turn their heads as they see me ride by But a little brown maverick is winking her eye Oh, what a beautiful mornin' I've got a beautiful feeling Everything's going my way All the sounds of the earth are like music All the sounds of the earth are like music The breeze is so busy, it don't miss a tree And an old weeping willow is laughing at me Oh, what a beautiful mornin' Oh, what a beautiful day I've got a beautiful feeling Everything's going my way Oh, what a beautiful day ALEXA I: With its character-driven songs and innovative use of dance, ‘Oklahoma’ elevated how musicals were written. -

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

Into the Woods Is Presented Through Special Arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI)

PREMIER SPONSOR ASSOCIATE SPONSOR MEDIA SPONSOR Music and Lyrics by Book by Stephen Sondheim James Lapine June 28-July 13, 2019 Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Original Broadyway production by Heidi Landesman Rocco Landesman Rick Steiner M. Anthony Fisher Frederic H. Mayerson Jujamcyn Theatres Originally produced by the Old Globe Theater, San Diego, CA. Scenic Design Costume Design Shoko Kambara† Megan Rutherford Lighting Design Puppetry Consultant Miriam Nilofa Crowe† Peter Fekete Sound Design Casting Director INTO The Jacqueline Herter Michael Cassara, CSA Woods Musical Director Choreographer/Associate Director Daniel Lincoln^ Andrea Leigh-Smith Production Stage Manager Production Manager Myles C. Hatch* Adam Zonder Director Michael Barakiva+ Into the Woods is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com Music and Lyrics by Book by STEPHEN JAMES Directed by SONDHEIM LAPINE MICHAEL * Member of Actor’s Equity Association, † USA - Member of Originally directed on Broadway by James LapineBARAKIVA the Union of Professional Actors and United Scenic Artists Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Stage Managers in the United States. Local 829. ^ Member of American Federation of Musicians, + Local 802 or 380. CAST NARRATOR ............................................................................................................................................HERNDON LACKEY* CINDERELLA -

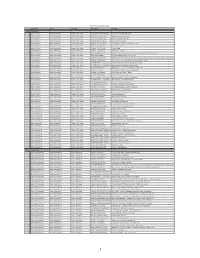

South West Regional Event List

South West Regional Festival Event Section Room Event Type School Name Event Title Senior Virtual Solo E Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical HILLSBOROUGH HIGH SCHOOL Here I Am - Dirty Rotten Scoundrels Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical Academy of the Holy Names What Only Love Can See-Caplin Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical Academy of the Holy Names Watch What Happens-Newsies Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical Academy of the Holy Names Dear Friend-She Loves Me Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical Academy of the Holy Names The Writing on the Wall-Mystery of Edwin Drood Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical Academy of the Holy Names Nothing-A Chorus Line Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical SUNLAKE HIGH SCHOOL In Short- Edges Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical SUNLAKE HIGH SCHOOL Screw Loose- Cry Baby Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical NEWSOME HIGH SCHOOL 096623 The Beauty Is from The Light in the Piazza by Adam Guettel and Craig Lucas Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical DAYSPRING ACADEMY Someone To Watch Over Me - Crazy For You Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical NEWSOME HIGH SCHOOL 096623 Getting There from In Transit by Kristen Anderson-Lopez, James-Allen Ford, Russ Kaplan and Sara Wordsworth Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical SUNLAKE HIGH SCHOOL Orphan at 33- Twisted- THE UNTOLD STORY OF A ROYAL VIZIER Senior SW Solo A Senior Virtual Solo E Musical - Solo Musical ST. -

BROADWAY BOUND: Mezer's Modest Proposals This Piece Comes to You Compliments of ACREL Fellow Steve Mezer of Becker & Poli

BROADWAY BOUND: Mezer’s Modest Proposals This piece comes to you compliments of ACREL Fellow Steve Mezer of Becker & Poliakoff who has a front row view of Broadway for several reasons. He is on the Board of the Straz Performing Arts Center in Tampa that invests in and presents Broadway shows. He is also a theater aficionado who spends his free time in NYC with his wife Karen bingeing on Broadway and Off Broadway musicals. Broadway theater is a unique American cultural experience. Other cities have vibrant theater scenes, but no other American venue offers Broadway’s range of options. I recommend that you come a day early and stay a date later for our Fall meeting in New York and take in a couple of Broadway shows. I grew up 90 miles outside of New York City; Broadway was and remains a family staple. I can neither sing nor dance, but I have a great appreciation for musical theater. So here are my recommendations: Musicals: 2016 was one of Broadway’s most successful years as it presented many original works and attracted unprecedented attention with Hamilton and its record breaking (secondary market) ticket prices. October is a transition month, an exciting time to see a new Broadway show. Holiday Inn, an Irving Berlin musical, begins previews September 1, and opens on October 6 at Studio 54. Jim (played by Bryce Pinkham) leaves his farm in Connecticut and meets Linda (Laura Lee Gayer) a school teacher brimming with talent. Together they turn a farmhouse into an inn with dazzling performances to celebrate each holiday. -

The Maple Shade Arts Council Summer Theatre the MAPLE SHADE Announces Our Summer Children's Show ARTS COUNCIL Once Upon a Mattress PROUDLY PRESENTS

The Maple Shade Arts Council Summer Theatre THE MAPLE SHADE announces our summer children's show ARTS COUNCIL Once Upon A Mattress PROUDLY PRESENTS PERFORMANCES: August 6 @ 7:30PM August 7 @ 7:30PM August 8 @ 2:00PM and 7:30PM Tickets: $10—adults $8—children/senior citizens Visit www.msartscouncil.org to purchase tickets today! For more information about the Summer Theatre program and how to register for next year, email [email protected] Bring in your playbill or ticket to July 10, 11, 12, 17, 18, 19 @ 7:30PM 114-116 E. MAIN ST. receive a 15% discount off your Maple Shade High School MAPLE SHADE, NJ 08052 bill. Valid before or after the (856)779-8003 performances on July 10-12 and Auditorium 17-19. Not valid with any other coupons, offers, or discounts. 2014 Sponsors OUR MISSION STATEMENT The Maple Shade Arts Council wishes to express our sincere gratitude to the many sponsors to our organization. The Maple Shade Arts Council is a non-profit organization We appreciate your support of the Arts Council. comprised of educators, parents, and community members whose objective is to provide artistic programs and events that will be entertaining, educational, and inspirational for the community. The Arts Council's programming emphasizes theatrical productions and workshops, yet also includes programming for the fine and performing arts. Maple Shade Arts Council Executive Board 2014 President Michael Melvin Vice President Jillian Starr-Renbjor Secretary AnnMarie Underwood Treasurer Matthew Maerten Publicity Director Rose Young Fundraising Director Debra Kleine Fine Arts Director Nancy Haddon *ALL CONCESSIONS WILL BE SOLD PRIOR TO THE SHOW BETWEEN 6:45PM-7:25PM—THERE WILL ONLY BE A BRIEF 10 MINUTE BATHROOM/SNACK BREAK AT INTERMISSION. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

P R E S S R E L E A

P R E S S R E L E A S E Contact: Tara Wibrew, OCT associate producer [email protected] 541.953.1038 (cell) For Immediate Release: November 30, 2020 From the Tony and Olivier Award-Winning Director of Les Misérables and Nicholas Nickleby John Caird and the Tony Nominated Composer of Jane Eyre Paul Gordon: A World Premiere Streaming Holiday Musical that Uniquely Blends Theatre, Film and Cutting-Edge Animation For a first look at the Trailer, click here: Estella Scrooge EUGENE, OR – Just in time for the holidays, Oregon Contemporary Theatre brings audiences a magical musical created with new cutting-edge technology that is sure to become new a holiday tradition – the World Premiere of Estella Scrooge: A Christmas Carol with a Twist! Estella Scrooge is now available for streaming through the holidays. Tickets are now on sale and may be purchased at https://bit.ly/OCTEstellaScrooge, or visit OCT’s website at octheatre.org. The production features a cast of 24 award-winning Broadway notables, and is the creation of John Caird, (the Tony and Olivier Award-winning director of Les Misérables and Nicholas Nickleby), and Tony Award nominee Paul Gordon (Jane Eyre, Pride and Prejudice). Caird and Gordon also paired to create Daddy Long Legs, which played at numerous regional theatres throughout the country and in four countries before enjoying a successful Off-Broadway run where Caird received a Drama Desk. The story follows Estella Scrooge, a modern-day Wall Street tycoon with a penchant for foreclosing. A hotelier in her hometown of Pickwick, Ohio has defaulted on his mortgage and Estella fancies the idea of lowering the boom personally. -

Bradley King and Beowulf Boritt

A Conversation With BRADLEY KING & BEOWULF BORITT Rendering of Flying Over Sunset - OPENING Book by James Lapine, Music by Tom Kitt, and Lyrics by Michael Korie Directed by James Lapine | Produced by Lincoln Center Theater Set by Beowulf Boritt | Lighting by Bradley King BACKGROUND LED tape is a unique lighting product in today’s entertainment world. Many disciplines of design interact with it - especially lighting and set designers. City Theatrical asked Tony Award winning lighting and scenic designers, Bradley King and Beowulf Boritt, about their work together on Broadway’s Flying Over Sunset to compare their perspectives on the show, LED tape and how they use it, what they see for the future of this LED technology, and their outlook on the future of the theater industry as a whole. Q&A: of our first preview in March 2020. We had LSD use pre-1960s. People think LSD and three invited dress audiences, so only a hippies, but before that, it was recommended City Theatrical (CTI): What is Flying Over handful of people were able to see it. by doctors as an antidepressant, essentially. Sunset about? What was it like to work on it? Bradley King: I agree, for many people the We stayed very far away from any tie show is a complete unknown. It was the dye imagery, and tried to bring a far more Beowulf Boritt: It is hard to say what Flying first realized production of this show ever. nuanced chromatic interpretation to the Over Sunset is, and I think [the writer and And there are not too many cold opens on experience of taking LSD.