UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juniors Pick Prom Queen; Call Lanin, Devron to Play

Vol. XLI, No. 15 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D, C. Thursday, February 18, 1960 Parents &. Profs History Fraternity Set Get-Together Names 4 Seniors Juniors Pick Prom Queen; For Next Sunday For Membership Next Sunday, February 21, Call Lanin, Devron To Play will witness the Washington The Georgetown Beta-Phi Club's Fifth Annual Recep chapter of Phi Alpha Theta, Coughlin Promises tion for the Faculty of the national honor history fra Hawaiian Weekend College and the parents of the ternity, founded in 1921, has non-resident students. recently elected four new The Junior Prom, a yearly A full afternoon has been members from the College. tradition here at the Hilltop, planned, beginning in Gaston Hall They are seniors John Cole will enliven the weekend of at 2 p.m. with a short concert by the Chimes and a greeting to the man, Bob Di Maio, Arnold February 26. The events are parents by Rev. Joseph A. Sellin Donahue, and Al Staebler. open to all students in the ger, Dean of the College. Under the auspices of Dr. Tibor . University, not just the junior Kerekes, the Georgetown chapter class. Chairman of the fete is im has grown, since its inception in presario Paul J. Coughlin. Cough 1948, to three hundred members lin is an AB (Classical) economics and is one of the most active in the fraternity. major and a member of the Class The first admitted among Catho of '61. He was on the Spring Week lic universities, it comprises mem end Committee last year and is bers from the College, Foreign present.ly a membe1.· of the N. -

Who's Telling My Story?

LESSON PLAN Level: Grades 9 to 12 About the Author: Matthew Johnson, Director of Education, MediaSmarts Duration: 2 to 3 hours This lesson was produced with the support of the Government of Canada through the Department of Justice Canada's Justice Partnership and Innovation Program. Who’s Telling My Story? This lesson is part of USE, UNDERSTAND & CREATE: A Digital Literacy Framework for Canadian Schools: http://mediasmarts.ca/teacher-resources/digital-literacy-framework. Overview In this lesson students learn about the history of blackface and other examples of majority-group actors playing minority -group characters such as White actors playing Asian and Aboriginal characters and non-disabled actors playing disabled characters. They consider the key media literacy concepts that “audiences negotiate meaning” and “media contain ideological and value messages and have social implications” in discussing how different kinds of representation have become unacceptable and how those kinds of representations were tied to stereotypes. Finally, students discuss current examples of majority-group actors playing minority-group characters and write and comment on blogs in which they consider the issues raised in the lesson. Learning Outcomes Students will: learn about the history and implications of majority-group actors playing minority-group characters consider the importance of self-representation by minority communities in the media state and support an opinion write a persuasive essay Preparation and Materials Read Analyzing Blackface (Teacher’s Copy) Prepare to show the A History of Blackface slideshow and Blackface Then and Now video to the class Copy the following handouts: Analyzing Blackface Cripface www.mediasmarts.ca 1 © 2016 MediaSmarts Who’s Telling My Story? ● Lesson Plan ● Grades 9 – 12 Procedure Begin by projecting the first two images from “A History of Blackface”: Carlo Rota and Kevin McHale, from series currently on TV (2011). -

Finery at Vinery

SOUTHEAST ALABAMA FLORIDA GEORGIA MISSISSIPPI NORTH CAROLINA SOUTH CAROLINA TENNESSEE Finery SOUTHEAST at Vinery In This Section LEADING SIRES IN FLORIDA BY 2011 PROGENY EARNINGS Florida training center under LEADING SIRES IN FLORIDA Ian Brennan sends out winners in bunches BY 2011 WINNERS BY LENNY SHULMAN ometimes it pays to be contrarian. While other operations have contracted over Advertisers’ the past few years, Tom Simon’s Vinery has gotten aggressive. It has supported Index Sits young stallions More Than Ready and Congrats and turned them into major success stories; it has enhanced its racing stable and come up with horses such as Kodiak Kowboy, a NATC champion in both the United States and Canada who 687 WWW.NATC.CC has now joined the Vinery stallion roster; and last year Vinery made its debut as a consignor of 2-year- VINERY SOUTH olds in training at various juvenile auctions. 689 WWW.VINERY.COM To achieve such success takes coordination among WINNING IMAGES PHOTOGRAPHY/JOSEPH DIORIO PHOTOS Ian Brennan directs Vinery's successful Florida training center 686 BloodHorse.com ■ MARCH 12, 2011 37% of our 2010 Graded Stakes Winning Graduates Won Grade I Stakes “From 2004-2008 buyers purchased 2,310 runners as juveniles for $100,000 or more. An impressive 14% went on to become stakes winners with 26% earning black type..” -The Blood-Horse MarketWatch, Feb. 2011 DAKOTA PHONE-G1 WICKEDLY PERFECT-G1 DEVIL MAY CARE-G1 Find your next Graded Stakes Winner at an upcoming Two-Year-Olds in Training Sale Mar. 15-16 OBS Selected Sale, Ocala, FL Mar. -

RODGERS, HAMMERSTEIN &Am

CONCERT NO. 1: IT'S ALL IN THE NUMBERS TUESDAY JUNE 14, 2005 ARTEL METZ DRIVE, 7:30 pm SOLOISTS: Trumpet Quartet Lancaster HS Concert Choir - Gary M. Lee, Director SECOND CENTURY MARCH A. Reed SECOND SUITE FOR BAND G. Holst FOUR OF A KIND J. Bullock Trumpet Quartet IRISH PARTY IN THIRD CLASS R. Saucedo SELECTIONS FROM A CHORUS LINE J. Cavacas IRVING BERLIN'S AMERICA J. Moss WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHIN' IN Traditional Lancaster HS Concert Choir - Gary M. Lee, Director 23 SKIDOO Whitcomb STAR SPANGLED SPECTACULAR G. Cohan GALLANT SEVENTH MARCH J. P. Sousa CONCERT NO. 2: RODGERS, HAMMERSTEIN & HART, WITH HEART TUESDAY JUNE 21, 2005 ARTEL METZ DRIVE, 7:30 pm SOLOISTS: Deborah Jasinski, Vocalist Bryan Banach, Piano Pre-Concert Guests: Lancaster H.S. Symphonic Band RICHARD RODGERS: SYMPHONIC MARCHES Williamson SALUTE TO RICHARD RODGERS T. Rickets LADY IS A TRAMP Hart/Rodgers/Wolpe Deborah Jasinski, Vocalist SHALL WE DANCE A. Miyagawa SHOWBOAT HIGHLIGHTS Hammerstein/Kerr SLAUGHTER ON 10TH AVENUE R. Saucedo Bryan Banach, Piano YOU'LL NEVER WALK ALONE arr. Foster GUADALCANAL MARCH Rodgers/Forsblad CONCERT NO. 3: SOMETHING OLD, NEW, BORROWED & BLUE TUESDAY JUNE 28, 2005 ARTEL METZ DRIVE, 7:30 pm SOLOISTS: Linda Koziol, Soloist Dan DeAngelis & Ben Pulley, Saxophones The LHS Acafellas NEW COLONIAL MARCH R. B. Hall THEMES LIKE OLD TIMES III Barker SHADES OF BLUE T. Reed Dan DeAngelis, Saxophone BLUE DEUCE M. Leckrone Dan DeAngelis & Ben Pulley, Saxophones MY OLD KENTUCKY HOME Foster/Barnes MY FAIR LADY Lerner/Lowe BLUE MOON Rodgers/Hart/Barker Linda Koziol, Soloist FINALE FROM NEW WORLD SYMPHONY Dvorak/Leidzon BOYS OF THE OLD BRIGADE Chambers CONCERT NO. -

Media Kit Fact Sheet P

Beaver MEDIA KIT Fact Sheet p. 2 Background p. 5 Faculty & Staff p. 6 Press Coverage p. 10 Presentations p. 13 Notable Alumni p. 14 College List p. 15 Beaver Country Day School Media Contact 791 Hammond Street Meredith Frazier Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 [email protected] Phone: 617-738-2700 617-738-2745 www.bcdschool.org 1 Beaver FACT SHEET Founded 130 1920 50%53% 50% Grades Middle School Students 6 - 12 Students from public Students from independent & charter schools & parochial schools Local Communities 338 (in and around Boston) 70 25% 25% 24% Languages Upper School 20 Students Students of color Faculty of color Financial aid OVERVIEW Beaver Country Day School is a NEASC- accredited school for grades six through 12 located three miles west of Boston in Brookline, Mass. Through its multidimensional approach to teaching, Beaver stands at the forefront of education and empowers students to succeed in today’s constantly-changing world. Innovative partnerships, challenging academics and a technology- driven educational environment make Beaver a leader in independent, college- preparatory education. Beaver students come from more than 70 communities in and around Boston and speak 20 different languages at home. MISSION Beaver offers an academically challenging curriculum in an environment that promotes balance in students’ lives. Deeply committed to individual student success, teachers inspire students to: • Reason and engage deeply with complex ideas and issues; • Be intellectually curious, open-minded and fair; • Identify and build upon their strengths; • Develop leadership and teamwork skills; • Act effectively within a genuinely diverse cultural and social framework; • Serve both school and society with integrity, respect and compassion. -

Glee: Uma Transmedia Storytelling E a Construção De Identidades Plurais

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE HUMANIDADES, ARTES E CIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CULTURA E SOCIEDADE ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Salvador 2012 ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa Multidisciplinar de Pós-graduação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, área de concentração: Cultura e Identidade. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler Salvador 2012 Sistema de Bibliotecas - UFBA Lima, Roberto Carlos Santana. Glee : uma Transmedia storytelling e a construção de identidades plurais / Roberto Carlos Santana Lima. - 2013. 107 f. Inclui anexos. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal da Bahia, Faculdade de Comunicação, Salvador, 2012. 1. Glee (Programa de televisão). 2. Televisão - Seriados - Estados Unidos. 3. Pluralismo cultural. 4. Identidade social. 5. Identidade de gênero. I. Thürler, Djalma. II. Universidade Federal da Bahia. Faculdade de Comunicação. III. Título. CDD - 791.4572 CDU - 791.233 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação aprovada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, Universidade Federal da Bahia, pela seguinte banca examinadora: Djalma Thürler – Orientador ------------------------------------------------------------- -

AMERICAN HORROR STORY TEMP 9 CAP 8 9 Pasfox

AMERICAN HORROR STORY TEMP 9 CAP 8 - 9 | Pasfox AMERICAN HORROR STORY TEMP 9 CAP 8 - 9 | Pasfox 1 / 3 2 / 3 Jun 29, 2020 — American Horror Story - 1984 (Temporada 9) capitulo 8 parte 19. 704 views704 views. Premiered Jun 29, 2020. Critics Consensus: A near-perfect blend of slasher tropes and American Horror Story's trademark twists, 1984 is a bloody good time. 2019, FX, 9 episodes, ... Oct 31, 2019 — Cast members from seasons past return to haunt the current AHS season. ... 10/01/19American Horror Story: 1984 | Season 9 Ep. 3: Slashdance .... Nov 14, 2019 — 'American Horror Story: 1984' will feature a killer soundtrack with a bunch of '80s classics during the season. ... Episode 9: Final Girl.. Oct 22, 2013 — Banda sonora de la serie American Horror Story: Coven*Intento actualizarla ... 8. House of the Rising Sun. Lauren O'Connell. 3:05. 9. Pie IX.. 29, 2021 American Horror Stories. iCarly 1×09. HD. Episodio 9. T1 E9 / Jul. ... Rápidos y Furiosos 9 (2021). 2021. Cielo rojo sangre (2021). 0. Destacado ... Sep 18, 2019 — American Horror Story Temporada 9 Trailer Oficial Subtitulado ... American Horror Story 6: Roanoke capítulo 8 y 9 | Review con spoilers.. La familia ingalls -Temporada 9 Cap 17 (5-5). 00:08:28 11.63 MB Series ... Battlestar Galactica de los 80 Episodio 2 cap 8 . 00:04:58 6.82 MB .... ... Freddy Krueger Jason Bracelet American Horror Story Classic Horror Movies ... Baggy Soft Slouchy Beanie Hat Stretch Infinity Scarf Head Wrap Cap, 8 Pack .... Dónde ver American Horror Story - Temporada 2? ¡Prueba a ver si Netflix, iTunes, Amazon o cualquier otro servicio te deja reproducirlo en streaming, .. -

The Rocky Horror Picture Show Movie Script Prepared and Edited By

The Rocky Horror Picture Show Movie Script Prepared and Edited by: George Burgyan ([email protected]) July 5 1993 The Rocky Horror Picture Show Movie Script HTTP://COPIONI.CORRIERESPETTACOLO.IT Cast: Dr. Frank-n-Furter (a scientist) Tim Curry Janet Weiss (a heroine) Susan Sarandon Brad Majors (a hero) Barry Bostwick Riff Raff (a handyman) Richard O'Brien Magenta (a domestic) Patricia Quinn Columbia (a groupie) Little Nell (Laura Campbell) Dr. Everett V. Scott (a rival scientist) Jonathan Adams Rocky Horror (a creation) Peter Hinwood Eddie (ex-delivery boy) Meat Loaf The Criminologist (Narrator) (an expert) Charles Gray The Transylvanians: Perry Bedden Fran Fullenwider Christopher Biggins Lindsay Ingram Gayle Brown Penny Ledger Ishaq Bux Annabelle Leventon Stephen Calcutt Anthony Milner Hugh Cecil Pamela Obermeyer Imogen Claire Tony Then Rufus Collins Kimi Wong Sadie Corre Henry Woolf Props: Rice Bouquet Rings Newspaper (preferred: Plain Dealer) Water (squirt gun, or whatever) Matches (failing which, another source of light) Doughnut / Bagel Rubber Gloves Noisemaker Confetti (torn newspapers work well) Toilet Paper (preferred: Scott brand) Paper Airplanes Toast Party Hat Bell Cards Credits (other than actors) Original Musical Play and Lyrics by Richard O'Brien { "Dick number one!" } Screenplay Jim Sharman Richard O'Brien { "Dick number two!" } Musical Direction and Arrangements Richard Hartley { "Dick number three!" } Director of Photography Peter Suschitzley { "What did they do?" } Film and Music Editor Graeme Clifford{"They creamed Clifford!"} -

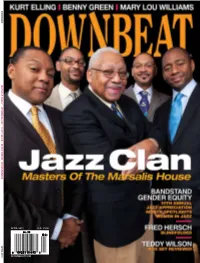

Downbeat.Com April 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. PRIL 2011 DOWNBEAT.COM A D OW N B E AT MARSALIS FAMILY // WOMEN IN JAZZ // KURT ELLING // BENNY GREEN // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2011 APRIL 2011 VOLume 78 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Maureen Flaherty ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, -

(XXXIX:9) Mel Brooks: BLAZING SADDLES (1974, 93M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

October 22, 2019 (XXXIX:9) Mel Brooks: BLAZING SADDLES (1974, 93m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Mel Brooks WRITING Mel Brooks, Norman Steinberg, Richard Pryor, and Alan Uger contributed to writing the screenplay from a story by Andrew Bergman, who also contributed to the screenplay. PRODUCER Michael Hertzberg MUSIC John Morris CINEMATOGRAPHY Joseph F. Biroc EDITING Danford B. Greene and John C. Howard The film was nominated for three Oscars, including Best Actress in a Supporting Role for Madeline Kahn, Best Film Editing for John C. Howard and Danford B. Greene, and for Best Music, Original Song, for John Morris and Mel Brooks, for the song "Blazing Saddles." In 2006, the National Film Preservation Board, USA, selected it for the National Film Registry. CAST Cleavon Little...Bart Gene Wilder...Jim Slim Pickens...Taggart Harvey Korman...Hedley Lamarr Madeline Kahn...Lili Von Shtupp Mel Brooks...Governor Lepetomane / Indian Chief Burton Gilliam...Lyle Alex Karras...Mongo David Huddleston...Olson Johnson Liam Dunn...Rev. Johnson Shows. With Buck Henry, he wrote the hit television comedy John Hillerman...Howard Johnson series Get Smart, which ran from 1965 to 1970. Brooks became George Furth...Van Johnson one of the most successful film directors of the 1970s, with Jack Starrett...Gabby Johnson (as Claude Ennis Starrett Jr.) many of his films being among the top 10 moneymakers of the Carol Arthur...Harriett Johnson year they were released. -

2016 IGNITION Festival Release 2016

Press contact: Cathy Taylor/Kelsey Moorhouse Cathy Taylor Public Relations [email protected] [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 773-564-9564 Victory Gardens Theater Announces Lineup for 2016 IGNITION Festival of New Plays 2016 Festival runs August 5–7, 2016 CHICAGO, IL – Victory Gardens Theater announces the lineup for the 2016 IGNITION Festival of New Plays, including The Wayward Bunny by Greg Kotis; BREACH: a manifesto on race in America through the eyes of a black girl recovering from self-hate by Antoinette Nwandu; EOM (end of message) by Laura Jacqmin; Kill Move Paradise by James Ijames; Gaza Rehearsal by Karen Hartman; and Girls In Cars Underwater by Tegan McLeod. The 2016 Festival runs August 5-7, 2016 at Victory Gardens Theater, located at 2433 N Lincoln Avenue. INGITION’s six selected plays will be presented in a festival of readings and will be directed by leading artists from Chicago. Following the readings, two of the plays may be selected for intensive workshops during Victory Gardens’ 2016-17 season, and Victory Gardens may produce one of these final scripts in an upcoming season. "At Victory Gardens Theater, we bridge Chicago communities through innovative and challenging new plays by giving established and emerging playwrights the time and space to develop their work. This year, we have invited some of the most thrilling playwrights to join our IGNITION Festival,” said Isaac Gomez, Victory Gardens Theater Literary Manager. “Their plays exemplify the current political and cultural zeitgeist of our city and country: the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, race and gender, the modern struggles of fatherhood, the insular world and morality of video gaming, and a woman’s journey to self-love. -

ZCH Audition Packet the Rocky Horror Picture Show by Richard O’Brien Directed by Alice Schroeder

ZCH Audition Packet The Rocky Horror Picture Show by Richard O’Brien Directed by Alice Schroeder We are the home to the Twin Ports premiere Rocky Horror Picture Show shadow cast. Officially registered with The Rocky Horror Fan Club, we have joined the network of shadow casts that are performing all throughout the world. This will be our tenth year performing The Rocky Horror Picture Show in the Twin Ports. Experience the tradition. This Halloween, venture out at night and join us for a lip syncing extravaganza you'll never forget. Audition Information AUDITIONS: September 11, 2021, 1:00PM This is a general audition, no appointment necessary. Please feel free to arrive a few minutes early to get settled before the auditions begin at 1pm. LOCATION: NorShor Theatre Rehearsal Studios, 211 East Superior Street, 3rd floor. Please enter through the "Lights on Duluth" door on Superior St next to the Box Office. Then take the stairs or elevator up to the third floor (N3). The rehearsal studios are down the hall to the right. PREPARATION: Watch the movie. Be prepared to learn the Time Warp. If auditioning for a specific role, please prepare the song selection listed next to character names below. Please bring a résumé, headshot, and audition form to your audition. Due to the nature and content of the show, participants must be 18 years of age by the time of auditions! MASKS: Masks are currently required to be worn by everyone inside the Norshor. Actors will be allowed to remove their mask when they are in the act of performing.