High Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ambito N°7 PRATO E VAL DI BISENZIO

QUADRO CONOSCITIVO Ambito n°7 PRATO E VAL DI BISENZIO PROVINCE : Firenze , Prato TERRITORI APPARTENENTI AI COMUNI : Calenzano, Campi Bisenzio, Cantagallo, Carmignano, Montemurlo, Poggio a Caiano, Prato, Signa, Vaiano, Vernio COMUNI INTERESSATI E POPOLAZIONE I comuni sono tutti quelli della provincia di Prato - Cantagallo, Carmignano, Montemurlo, Poggio a Caiano, Prato, Vaiano, Vernio - e parte del territorio dei Comuni di Campi Bisenzio e Calenzano, nella provincia di Firenze. L’incremento della popolazione in 30 anni è poco meno del 26%, il più elevato fra le aree della Toscana. L’unico grande centro urbano è Prato, che era fino al 1991 la terza città della Toscana, e in seguito la seconda, avendo sorpassato Livorno. Gli altri comuni sono tutti in crescita, in vari casi hanno ripreso a crescere dopo fasi più o meno lunghe di calo. Ad esempio, Carmignano: cresce fino al 1911, quando Poggio a Caiano era una sua frazione, e sfiora i 9000 abitanti, e riprende poi una moderata crescita; Poggio a Caiano, formato nel 1962, è da allora in crescita sostenuta (nel 2001 ha il 190% della popolazione legale della frazione esistente nel 1951). Vernio aumenta fino al 1931 (probabilmente in relazione alla costruzione della grande galleria ferroviaria appenninica) sfiorando i 9.000 residenti; poi cala, stabilizzandosi a partire dal 1981. Il numero dei residenti è quasi sestuplicato (570,8%) nei 50 anni dal 1951 al 2001: è senza dubbio il comune toscano che ha avuto un più forte ritmo di crescita. L’insediamento urbano recente è cresciuto occupando il fondovalle anche con insediamenti produttivi, sebbene essi oggi non abbiano il radicamento territoriale di quelli storici rispetto alla disponibilità di acqua, cosicché sono frequenti gli squilibri di scala rispetto alle dimensioni della sezione del fondovalle (Vaiano). -

Arch 242: Building History Ii

ARCH 242: BUILDING HISTORY II Renaissance & Baroque: Rise & Evolution of the Architect 01 AGENDA FOR TODAY . GIULIANO DA SANGALLO - The Renaissance Architect - The spread of the Renaissance - The centralized church plan - Santa Maria delle Carceri - Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano - Plan for Saint Peter’s - Discussion 02 GIULIANO DA SANGALLO Giuliano Da Sangallo, 1443-1516 - Born in Florence, Italy - Projects near Florence, Prato, and Rome, Italy 03 LOCATIONS IN ITALY Prato Florence Rome Map of Italy 04 GIULIANO DA SANGALLO Giuliano Da Sangallo, 1443-1516 - Born in Florence, Italy - Projects near Florence, Prato, and Rome, Italy - Worked as a sculptor, architect, and military engineer 05 RENAISSANCE STUDENT Filippo Brunelleschi Leon Battista Alberti 06 GIULIANO DA SANGALLO Giuliano Da Sangallo, 1443-1516 - Born in Florence, Italy - Projects near Florence, Prato, and Rome, Italy - Worked as a sculptor, architect, and military engineer - The Renaissance Architect 07 SANGALLO IN ROME Ancient Roman Theater of Marcellus Ruins Crypta Balbi engraving - Sangallo’s drawing 08 THE CENTRALLY PLANNED CHURCH Appeared during the High Renaissance - Many centrally planned churches sprung up between 1480 & 1510 - Symbolized the perfection of god as well as nature; particularly those in the shape of a perfect circle - Satisfied the Humanist mission to find links between nature and art San Sebastiano, Alberti, 1460 09 RENAISSANCE HUMANISM The humanist movement spread throughout Italy - Upheld empirical observation and experience - Humanist ideas stemmed -

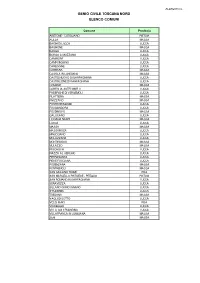

Allegato C Genio Civile Toscana Nord Elenco Comuni

ALLEGATO C GENIO CIVILE TOSCANA NORD ELENCO COMUNI Comune Provincia ABETONE - CUTIGLIANO PISTOIA AULLA MASSA BAGNI DI LUCCA LUCCA BAGNONE MASSA BARGA LUCCA BORGO A MOZZANO LUCCA CAMAIORE LUCCA CAMPORGIANO LUCCA CAREGGINE LUCCA CARRARA MASSA CASOLA IN LUNIGIANA MASSA CASTELNUOVO DI GARFAGNANA LUCCA CASTIGLIONE DI GARFAGNANA LUCCA COMANO MASSA COREGLIA ANTELMINELLI LUCCA FABBRICHE DI VERGEMOLI LUCCA FILATTIERA MASSA FIVIZZANO MASSA FORTE DEI MARMI LUCCA FOSCIANDORA LUCCA FOSDINOVO MASSA GALLICANO LUCCA LICCIANA NARDI MASSA LUCCA LUCCA MASSA MASSA MASSAROSA LUCCA MINUCCIANO LUCCA MOLAZZANA LUCCA MONTIGNOSO MASSA MULAZZO MASSA PESCAGLIA LUCCA PIAZZA AL SERCHIO LUCCA PIETRASANTA LUCCA PIEVE FOSCIANA LUCCA PODENZANA MASSA PONTREMOLI MASSA SAN GIULIANO TERME PISA SAN MARCELLO PISTOIESE - PITEGLIO PISTOIA SAN ROMANO IN GARFAGNANA LUCCA SERAVEZZA LUCCA SILLANO GIUNCUGNANO LUCCA STAZZEMA LUCCA TRESANA MASSA VAGLI DI SOTTO LUCCA VECCHIANO PISA VIAREGGIO LUCCA VILLA COLLEMANDINA LUCCA VILLAFRANCA IN LUNIGIANA MASSA ZERI MASSA ALLEGATO C GENIO CIVILE VALDARNO SUPERIORE ELENCO COMUNI Comune Provincia ANGHIARI AREZZO AREZZO AREZZO BADIA TEDALDA AREZZO BAGNO A RIPOLI FIRENZE BARBERINO DI MUGELLO FIRENZE BIBBIENA AREZZO BORGO SAN LORENZO FIRENZE BUCINE AREZZO CAPOLONA -CASTIGLION FIBOCCHI AREZZO CAPRESE MICHELANGELO AREZZO CASTEL FOCOGNANO AREZZO CASTEL SAN NICCOLO' AREZZO CASTELFRANCO - PIANDISCO' AREZZO CASTIGLION FIORENTINO AREZZO CAVRIGLIA AREZZO CHITIGNANO AREZZO CHIUSI DELLA VERNA AREZZO CIVITELLA IN VAL DI CHIANA AREZZO CORTONA AREZZO DICOMANO -

Prato and Montemurlo Tuscany That Points to the Future

Prato Area Prato and Montemurlo Tuscany that points to the future www.pratoturismo.it ENG Prato and Montemurlo Prato and Montemurlo one after discover treasures of the Etruscan the other, lying on a teeming and era, passing through the Middle busy plain, surrounded by moun- Ages and reaching the contempo- tains and hills in the heart of Tu- rary age. Their geographical posi- scany, united by a common destiny tion is strategic for visiting a large that has made them famous wor- part of Tuscany; a few kilometers ldwide for the production of pre- away you can find Unesco heritage cious and innovative fabrics, offer sites (the two Medici Villas of Pog- historical, artistic and landscape gio a Caiano and Artimino), pro- attractions of great importance. tected areas and cities of art among Going to these territories means the most famous in the world, such making a real journey through as Florence, Lucca, Pisa and Siena. time, through artistic itineraries to 2 3 Prato contemporary city between tradition and innovation PRATO CONTEMPORARY CITY BETWEEN TRADITION AND INNOVATION t is the second city in combination is in two highly repre- Tuscany and the third in sentative museums of the city: the central Italy for number Textile Museum and the Luigi Pec- of inhabitants, it is a ci Center for Contemporary Art. The contemporary city ca- city has written its history on the art pable of combining tradition and in- of reuse, wool regenerated from rags novation in a synthesis that is always has produced wealth, style, fashion; at the forefront, it is a real open-air the art of reuse has entered its DNA laboratory. -

Janson. History of Art. Chapter 16: The

16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 556 16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 557 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER The High Renaissance in Italy, 1495 1520 OOKINGBACKATTHEARTISTSOFTHEFIFTEENTHCENTURY , THE artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1550, Truly great was the advancement conferred on the arts of architecture, painting, and L sculpture by those excellent masters. From Vasari s perspective, the earlier generation had provided the groundwork that enabled sixteenth-century artists to surpass the age of the ancients. Later artists and critics agreed Leonardo, Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, and with Vasari s judgment that the artists who worked in the decades Titian were all sought after in early sixteenth-century Italy, and just before and after 1500 attained a perfection in their art worthy the two who lived beyond 1520, Michelangelo and Titian, were of admiration and emulation. internationally celebrated during their lifetimes. This fame was For Vasari, the artists of this generation were paragons of their part of a wholesale change in the status of artists that had been profession. Following Vasari, artists and art teachers of subse- occurring gradually during the course of the fifteenth century and quent centuries have used the works of this 25-year period which gained strength with these artists. Despite the qualities of between 1495 and 1520, known as the High Renaissance, as a their births, or the differences in their styles and personalities, benchmark against which to measure their own. Yet the idea of a these artists were given the respect due to intellectuals and High Renaissance presupposes that it follows something humanists. -

IN FOCUS: COUNTRYSIDE of TUSCANY, ITALY Nana Boussia Associate

MAY 2017 | PRICE €400 IN FOCUS: COUNTRYSIDE OF TUSCANY, ITALY Nana Boussia Associate Pavlos Papadimitriou, MRICS Associate Director Ezio Poinelli Senior Director Southern Europe HVS.com HVS ATHENS | 17 Posidonos Ave. 5th Floor, 17455 Alimos, Athens, GREECE HVS MILAN | Piazza 4 Novembre, 7, 20124 Milan, ITALY Introduction 2 Tuscany is a region in central Italy with an area of about 23,000 km and a LOCATION OF TUSCANY population of about 3.8 million (2013). The regional capital and most populated town is Florence with approximately 370,000 inhabitants while it features a Western coastline of 400 kilometers overlooking the Ligurian Sea (in the North) and the Tyrrhenian Sea (in the Center and South). Tuscany is known for its landscapes, traditions, history, artistic legacy and its influence on high culture. It is regarded as the birthplace of the Italian Renaissance, the home of many influential in the history of art and science, and contains well-known museums such as the Uffizi and the Pitti Palace. Tuscany produces several well-known wines, including Chianti, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, Morellino di Scansano and Brunello di Montalcino. Having a strong linguistic and cultural identity, it is sometimes considered "a nation within a nation". Seven Tuscan localities have been designated World Heritage Sites by UNESCO: the historic centre of Florence (1982); the historical centre of Siena (1995); the square of the Cathedral of Pisa (1987); the historical centre of San Gimignano (1990); the historical centre of Pienza (1996); the Val d'Orcia (2004), and the Medici Villas and Gardens (2013). Tuscany has over 120 protected nature reserves, making Tuscany and its capital Florence popular tourist destinations that attract millions of tourists every year. -

Catalogue-Garden.Pdf

GARDEN TOURS Our Garden Tours are designed by an American garden designer who has been practicing in Italy for almost 15 years. Since these itineraries can be organized either for independent travelers or for groups , and they can also be customized to best meet the client's requirements , prices are on request . Tuscany Garden Tour Day 1 Florence Arrival in Florence airport and private transfer to the 4 star hotel in the historic centre of Florence. Dinner in a renowned restaurant in the historic centre. Day 2 Gardens in Florence In the morning meeting with the guide at the hotel and transfer by bus to our first Garden Villa Medici di Castello .The Castello garden commissioned by Cosimo I de' Medici in 1535, is one of the most magnificent and symbolic of the Medici Villas The garden, with its grottoes, sculptures and water features is meant to be an homage to the good and fair governing of the Medici from the Arno to the Apennines. The many statues, commissioned from famous artists of the time and the numerous citrus trees in pots adorn this garden beautifully. Then we will visit Villa Medici di Petraia. The gardens of Villa Petraia have changed quite significantly since they were commissioned by Ferdinando de' Medici in 1568. The original terraces have remained but many of the beds have been redesigned through the ages creating a more gentle and colorful style. Behind the villa we find the park which is a perfect example of Mittle European landscape design. Time at leisure for lunch, in the afternoon we will visit Giardino di Boboli If one had time to see only one garden in Florence, this should be it. -

Renaissance Gardens of Italy

Renaissance Gardens of Italy By Daniel Rosenberg Trip undertaken 01-14 August 2018 1 Contents: Page: Introduction and overview 3 Itinerary 4-5 Villa Adriana 6-8 Villa D’Este 9-19 Vatican 20-24 Villa Aldobrindini 25-31 Palazzo Farnese 32-36 Villa Lante 37-42 Villa Medici 43-45 Villa della Petraia 46-48 Boboli Gardens 49-51 Botanical Gardens Florence 52 Isola Bella 53-57 Isola Madre 58-60 Botanic Alpine Garden Schynige Platte (Switz.) 61-62 Botanic Gardens Villa Taranto 63-65 Future Plans 66 Final Budget Breakdown 66 Acknowledgments 66 Bibliography 66 2 Introduction and Overview of project I am currently employed as a Botanical Horticulturalist at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. I started my horticultural career later in life and following some volunteer work in historic gardens and completing my RHS level 2 Diploma, I was fortunate enough to secure a place on the Historic and Botanic Garden training scheme. I spent a year at Kensington Palace Gardens as part of the scheme. Following this I attended the Kew Specialist Certificate in Ornamental Horticulture which gave me the opportunity to deepen my plant knowledge and develop my interest in working in historic gardens. While on the course I was able to attend a series of lectures in garden history. My interest was drawn to the renaissance gardens of Italy, which have had a significant influence on European garden design and in particular on English Gardens. It seems significant that in order to understand many of the most important historic gardens in the UK one must understand the design principles and forms, and the classical references and structures of the Italian renaissance. -

The Baroque Underworld Vice and Destitution in Rome

press release The Baroque Underworld Vice and Destitution in Rome Bartolomeo Manfredi, Tavern Scene with a Lute Player, 1610-1620, private collection The French Academy in Rome – Villa Medici Grandes Galeries, 7 October 2014 – 18 January 2015 6 October 2014 11:30 a.m. press premiere 6:30 p.m. – 8:30 p.m. inauguration Curators : Annick Lemoine and Francesca Cappelletti The French Academy in Rome - Villa Medici will present the exhibition The Baroque Underworld. Vice and Destitution in Rome, in the Grandes Galeries from 7 October 2014 to 18 January 2015 . Curators are Francesca Cappelletti, professor of history of modern art at the University of Ferrara and Annick Lemoine, officer in charge of the Art history Department at the French Academy in Rome, lecturer at the University of Rennes 2. The exhibition has been conceived and organized within the framework of a collaboration between the French Academy in Rome – Villa Medici and the Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, where it will be shown from 24 February to 24 May 2015. The Baroque Underworld reveals the insolent dark side of Baroque Rome, its slums, taverns, places of perdition. An "upside down Rome", tormented by vice, destitution, all sorts of excesses that underlie an amazing artistic production, all of which left their mark of paradoxes and inventions destined to subvert the established order. This is the first exhibition to present this neglected aspect of artistic creation at the time of Caravaggio and Claude Lorrain’s Roman period, unveiling the clandestine face of the Papacy’s capital, which was both sumptuous and virtuosic, as well as the dark side of the artists who lived there. -

Saggio Brothers

Cammy Brothers Reconstruction as Design: Giuliano da Sangallo and the “palazo di mecenate” on the Quirinal Hill this paper I will survey information regarding both the condition and conception of the mon- ument in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. When Giuliano saw the temple, the only fragments left standing were a portion of the façade and parts of the massive stair structure. His seven drawings of the monument were the first attempts to reconstruct the entire building, as well as the most complex and large scale reconstructions that he ever executed. The sec- ond part of this essay will compare Giuliano’s drawings with those of Peruzzi and Palladio, with the aim of demonstrating, contrary to the theory that drawings after the antique became increasingly accurate over time, that Giuliano in fact took fewer liberties in his reconstruction than did Palladio. Aside from providing some insight into Giuliano’s working method, I hope through this comparison to suggest that fif- teenth- and sixteenth-century drawings of antiquities cannot appropriately be judged according to one standard, because each archi- 1. Antonio Tempesta, Map of Rome, Giuliano da Sangallo’s drawings have suffered tect had his own particular aims. Giuliano’s 1593, showing fragments of the temple by comparison to those of his nephew, Antonio drawings suggest that he approached recon- as they appeared in the Renaissance. da Sangallo il Giovane. Although his drawings struction not with the attitude we would expect are more beautiful, they are on the whole less of a present day archaeologist, but rather with accurate, or at least less consistent in their mode that of a designer, keen to understand the ruins of representation and their use of measure- in terms that were meaningful for his own work. -

The Ballatoio of S. Maria Del Fiore in Florence Alessandro Nova

Originalveröffentlichung in: Millon, Henry A. (Hrsg.): The Renaissance from Brunelleschi to Michelangelo : the representation of architecture, London 1994, S. 591-597 The Ballatoio of S. Maria del Fiore in Florence Alessandro Nova The ballatoio is the only part of Florence Cathedral that 1.17 meters high and proportional to the existing one at was never completed, and the complex developments sur the base of the tribunes. This proposal is far removed rounding its fate are matter of debate. As far as the models from Brunelleschi ’s architectural language and, in fact, is in the Museo dell’Opera are concerned, there is a telling no more than a description of what we see in Andrea di report prepared in 1601 by Alessandro Allori, architect in Bonaiuto ’s fresco, in other words, a description of the charge of the building ’s maintenance, suggesting that model of 1367. The second solution, which proposed a they be inventoried to ascertain their original purpose double passage, covered below and open above, is the one (Guasti 1857:157), and hence by the time Florence was Brunelleschi most likely aimed to realize. under the rule of the grand dukes, the real purpose of The building records reveal that the brick model that the these models had already been forgotten. Such problems architect had built in 1418 was embellished by a wooden are compounded by the occasionally generic information ballatoio and lantern, whose construction had involved provided by the sources, the not always reliable attribu the contribution of Nanni di Banco and Donatello tions of modern critics, and the appalling damage caused (Saalman 1980: 62). -

Donato Bramante 1 Donato Bramante

Donato Bramante 1 Donato Bramante Donato Bramante Donato Bramante Birth name Donato di Pascuccio d'Antonio Born 1444Fermignano, Italy Died 11 April 1514 (Aged about 70)Rome Nationality Italian Field Architecture, Painting Movement High Renaissance Works San Pietro in Montorio Christ at the column Donato Bramante (1444 – 11 March 1514) was an Italian architect, who introduced the Early Renaissance style to Milan and the High Renaissance style to Rome, where his most famous design was St. Peter's Basilica. Urbino and Milan Bramante was born in Monte Asdrualdo (now Fermignano), under name Donato di Pascuccio d'Antonio, near Urbino: here, in 1467 Luciano Laurana was adding to the Palazzo Ducale an arcaded courtyard and other features that seemed to have the true ring of a reborn antiquity to Federico da Montefeltro's ducal palace. Bramante's architecture has eclipsed his painting skills: he knew the painters Melozzo da Forlì and Piero della Francesca well, who were interested in the rules of perspective and illusionistic features in Mantegna's painting. Around 1474, Bramante moved to Milan, a city with a deep Gothic architectural tradition, and built several churches in the new Antique style. The Duke, Ludovico Sforza, made him virtually his court architect, beginning in 1476, with commissions that culminated in the famous trompe-l'oeil choir of the church of Santa Maria presso San Satiro (1482–1486). Space was limited, and Bramante made a theatrical apse in bas-relief, combining the painterly arts of perspective with Roman details. There is an octagonal sacristy, surmounted by a dome. In Milan, Bramante also built the tribune of Santa Maria delle Grazie (1492–99); other early works include the cloisters of Sant'Ambrogio, Milan (1497–1498), and some other constructions in Pavia and possibly Legnano.