Fossil Primates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World at the Time of Messel: Conference Volume

T. Lehmann & S.F.K. Schaal (eds) The World at the Time of Messel - Conference Volume Time at the The World The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 2011 Frankfurt am Main, 15th - 19th November 2011 ISBN 978-3-929907-86-5 Conference Volume SENCKENBERG Gesellschaft für Naturforschung THOMAS LEHMANN & STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL (eds) The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference Frankfurt am Main, 15th – 19th November 2011 Conference Volume Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung IMPRINT The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Conference Volume Publisher PROF. DR. DR. H.C. VOLKER MOSBRUGGER Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Editors DR. THOMAS LEHMANN & DR. STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected]; [email protected] Language editors JOSEPH E.B. HOGAN & DR. KRISTER T. SMITH Layout JULIANE EBERHARDT & ANIKA VOGEL Cover Illustration EVELINE JUNQUEIRA Print Rhein-Main-Geschäftsdrucke, Hofheim-Wallau, Germany Citation LEHMANN, T. & SCHAAL, S.F.K. (eds) (2011). The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates. 22nd International Senckenberg Conference. 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main. Conference Volume. Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, Frankfurt am Main. pp. 203. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

Dryopithecins, Darwin, de Bonis, and the European origin of the African apes and human clade David R. BEGUN University of Toronto, Department of Anthropology, 19 Russell Street, Toronto, ON, M5S 2S2 (Canada) [email protected] Begun R. D. 2009. — Dryopithecins, Darwin, de Bonis, and the European origin of the African apes and human clade. Geodiversitas 31 (4) : 789-816. ABSTRACT Darwin famously opined that the most likely place of origin of the common ancestor of African apes and humans is Africa, given the distribution of its liv- ing descendents. But it is infrequently recalled that immediately afterwards, Darwin, in his typically thorough and cautious style, noted that a fossil ape from Europe, Dryopithecus, may instead represent the ancestors of African apes, which dispersed into Africa from Europe. Louis de Bonis and his collaborators were the fi rst researchers in the modern era to echo Darwin’s suggestion about apes from Europe. Resulting from their spectacular discoveries in Greece over several decades, de Bonis and colleagues have shown convincingly that African KEY WORDS ape and human clade members (hominines) lived in Europe at least 9.5 million Mammalia, years ago. Here I review the fossil record of hominoids in Europe as it relates to Primates, Dryopithecus, the origins of the hominines. While I diff er in some details with Louis, we are Hispanopithecus, in complete agreement on the importance of Europe in determining the fate Rudapithecus, of the African ape and human clade. Th ere is no doubt that Louis de Bonis is Ouranopithecus, hominine origins, a pioneer in advancing our understanding of this fascinating time in our evo- new subtribe. -

Human Evolution: a Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H

PHYSICAL (BIOLOGICAL) ANTHROPOLOGY - Human Evolution: A Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H. Smith HUMAN EVOLUTION: A PALEOANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE F.H. Smith Department of Anthropology, Loyola University Chicago, USA Keywords: Human evolution, Miocene apes, Sahelanthropus, australopithecines, Australopithecus afarensis, cladogenesis, robust australopithecines, early Homo, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Australopithecus africanus/Australopithecus garhi, mitochondrial DNA, homology, Neandertals, modern human origins, African Transitional Group. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Reconstructing Biological History: The Relationship of Humans and Apes 3. The Human Fossil Record: Basal Hominins 4. The Earliest Definite Hominins: The Australopithecines 5. Early Australopithecines as Primitive Humans 6. The Australopithecine Radiation 7. Origin and Evolution of the Genus Homo 8. Explaining Early Hominin Evolution: Controversy and the Documentation- Explanation Controversy 9. Early Homo erectus in East Africa and the Initial Radiation of Homo 10. After Homo erectus: The Middle Range of the Evolution of the Genus Homo 11. Neandertals and Late Archaics from Africa and Asia: The Hominin World before Modernity 12. The Origin of Modern Humans 13. Closing Perspective Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS The basic course of human biological history is well represented by the existing fossil record, although there is considerable debate on the details of that history. This review details both what is firmly understood (first echelon issues) and what is contentious concerning humanSAMPLE evolution. Most of the coCHAPTERSntention actually concerns the details (second echelon issues) of human evolution rather than the fundamental issues. For example, both anatomical and molecular evidence on living (extant) hominoids (apes and humans) suggests the close relationship of African great apes and humans (hominins). That relationship is demonstrated by the existing hominoid fossil record, including that of early hominins. -

The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research

Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Edited by Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham Chapters written in honour of Professor Colin P Groves Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Taxonomic tapestries : the threads of evolutionary, behavioural and conservation research / Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham, editors. ISBN: 9781925022360 (paperback) 9781925022377 (ebook) Subjects: Biology--Classification. Biology--Philosophy. Human ecology--Research. Coexistence of species--Research. Evolution (Biology)--Research. Taxonomists. Other Creators/Contributors: Behie, Alison M., editor. Oxenham, Marc F., editor. Dewey Number: 578.012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph courtesy of Hajarimanitra Rambeloarivony Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents List of Contributors . .vii List of Figures and Tables . ix PART I 1. The Groves effect: 50 years of influence on behaviour, evolution and conservation research . 3 Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham PART II 2 . Characterisation of the endemic Sulawesi Lenomys meyeri (Muridae, Murinae) and the description of a new species of Lenomys . 13 Guy G Musser 3 . Gibbons and hominoid ancestry . 51 Peter Andrews and Richard J Johnson 4 . -

Unravelling the Positional Behaviour of Fossil Hominoids: Morphofunctional and Structural Analysis of the Primate Hindlimb

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Doctorado en Biodiversitat Facultad de Ciènces Tesis doctoral Unravelling the positional behaviour of fossil hominoids: Morphofunctional and structural analysis of the primate hindlimb Marta Pina Miguel 2016 Memoria presentada por Marta Pina Miguel para optar al grado de Doctor por la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, programa de doctorado en Biodiversitat del Departamento de Biologia Animal, de Biologia Vegetal i d’Ecologia (Facultad de Ciències). Este trabajo ha sido dirigido por el Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont) y el Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez (The George Washington Univertisy). Director Co-director Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez A mis padres y hermana. Y a todas aquelas personas que un día decidieron perseguir un sueño Contents Acknowledgments [in Spanish] 13 Abstract 19 Resumen 21 Section I. Introduction 23 Hominoid positional behaviour The great apes of the Vallès-Penedès Basin: State-of-the-art Section II. Objectives 55 Section III. Material and Methods 59 Hindlimb fossil remains of the Vallès-Penedès hominoids Comparative sample Area of study: The Vallès-Penedès Basin Methodology: Generalities and principles Section IV. -

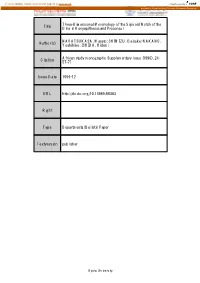

Title Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of the Title Ulna in Kenyapithecus and Proconsul NAKATSUKASA, Masato; SHIMIZU, Daisuke; NAKANO, Author(s) Yoshihiko; ISHIDA, Hidemi African study monographs. Supplementary issue (1996), 24: Citation 57-71 Issue Date 1996-12 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68383 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 24: 57-71, December 1996 57 THREE-DIMENSIONAL MORPHOLOGY OF THE SIGMOID NOTCH OF THE ULNA IN KENYAPITHECUS AND PROCONSUL Masato Nakatsukasa Daisuke Shimizu Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University Yoshihiko Nakano Department of Biological Anthropology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Osaka University Hidemi Ishida Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University ABSTRACT The three-dimensional (3-D) morphology of the sigmoid notch was examined in Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, and several living anthropoids by using an automatic 3-D digitizer. It was revealed that Kenyapithecus and Proconsul exhibit a very similar morphology of the dis tal region of the sigmoid notch; including the absence of a median keel and a downward sloped coronoid process. In addition, the proxilnal region of the sigmoid notch is curved more acutely relative to the distal region in Proconsul. This morphological complex is unique and not found in the examined living primates. The benefits of 3-D morphometries are discussed. Key Words: Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, sigmoid notch, three-dimensional morphometrics, ulna. INTRODUCTION Recently, automatic three-dimensional (3-0) digitizers have become more fre quently to be used for biometrics. -

Chapter 1 - Introduction

EURASIAN MIDDLE AND LATE MIOCENE HOMINOID PALEOBIOGEOGRAPHY AND THE GEOGRAPHIC ORIGINS OF THE HOMININAE by Mariam C. Nargolwalla A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright by M. Nargolwalla (2009) Eurasian Middle and Late Miocene Hominoid Paleobiogeography and the Geographic Origins of the Homininae Mariam C. Nargolwalla Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto 2009 Abstract The origin and diversification of great apes and humans is among the most researched and debated series of events in the evolutionary history of the Primates. A fundamental part of understanding these events involves reconstructing paleoenvironmental and paleogeographic patterns in the Eurasian Miocene; a time period and geographic expanse rich in evidence of lineage origins and dispersals of numerous mammalian lineages, including apes. Traditionally, the geographic origin of the African ape and human lineage is considered to have occurred in Africa, however, an alternative hypothesis favouring a Eurasian origin has been proposed. This hypothesis suggests that that after an initial dispersal from Africa to Eurasia at ~17Ma and subsequent radiation from Spain to China, fossil apes disperse back to Africa at least once and found the African ape and human lineage in the late Miocene. The purpose of this study is to test the Eurasian origin hypothesis through the analysis of spatial and temporal patterns of distribution, in situ evolution, interprovincial and intercontinental dispersals of Eurasian terrestrial mammals in response to environmental factors. Using the NOW and Paleobiology databases, together with data collected through survey and excavation of middle and late Miocene vertebrate localities in Hungary and Romania, taphonomic bias and sampling completeness of Eurasian faunas are assessed. -

New Hominoid Mandible from the Early Late Miocene Irrawaddy Formation in Tebingan Area, Central Myanmar Masanaru Takai1*, Khin Nyo2, Reiko T

Anthropological Science Advance Publication New hominoid mandible from the early Late Miocene Irrawaddy Formation in Tebingan area, central Myanmar Masanaru Takai1*, Khin Nyo2, Reiko T. Kono3, Thaung Htike4, Nao Kusuhashi5, Zin Maung Maung Thein6 1Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, 41 Kanrin, Inuyama, Aichi 484-8506, Japan 2Zaykabar Museum, No. 1, Mingaradon Garden City, Highway No. 3, Mingaradon Township, Yangon, Myanmar 3Keio University, 4-1-1 Hiyoshi, Kouhoku-Ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa 223-8521, Japan 4University of Yangon, Hlaing Campus, Block (12), Hlaing Township, Yangon, Myanmar 5Ehime University, 2-5 Bunkyo-cho, Matsuyama, Ehime 790-8577, Japan 6University of Mandalay, Mandalay, Myanmar Received 14 August 2020; accepted 13 December 2020 Abstract A new medium-sized hominoid mandibular fossil was discovered at an early Late Miocene site, Tebingan area, south of Magway city, central Myanmar. The specimen is a left adult mandibular corpus preserving strongly worn M2 and M3, fragmentary roots of P4 and M1, alveoli of canine and P3, and the lower half of the mandibular symphysis. In Southeast Asia, two Late Miocene medium-sized hominoids have been discovered so far: Lufengpithecus from the Yunnan Province, southern China, and Khoratpithecus from northern Thailand and central Myanmar. In particular, the mandibular specimen of Khoratpithecus was discovered from the neighboring village of Tebingan. However, the new mandible shows apparent differences from both genera in the shape of the outline of the mandibular symphyseal section. The new Tebingan mandible has a well-developed superior transverse torus, a deep intertoral sulcus (= genioglossal fossa), and a thin, shelf-like inferior transverse torus. In contrast, Lufengpithecus and Khoratpithecus each have very shallow intertoral sulcus and a thick, rounded inferior transverse torus. -

Constraints on the Timescale of Animal Evolutionary History

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history Michael J. Benton, Philip C.J. Donoghue, Robert J. Asher, Matt Friedman, Thomas J. Near, and Jakob Vinther ABSTRACT Dating the tree of life is a core endeavor in evolutionary biology. Rates of evolution are fundamental to nearly every evolutionary model and process. Rates need dates. There is much debate on the most appropriate and reasonable ways in which to date the tree of life, and recent work has highlighted some confusions and complexities that can be avoided. Whether phylogenetic trees are dated after they have been estab- lished, or as part of the process of tree finding, practitioners need to know which cali- brations to use. We emphasize the importance of identifying crown (not stem) fossils, levels of confidence in their attribution to the crown, current chronostratigraphic preci- sion, the primacy of the host geological formation and asymmetric confidence intervals. Here we present calibrations for 88 key nodes across the phylogeny of animals, rang- ing from the root of Metazoa to the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens. Close attention to detail is constantly required: for example, the classic bird-mammal date (base of crown Amniota) has often been given as 310-315 Ma; the 2014 international time scale indicates a minimum age of 318 Ma. Michael J. Benton. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Philip C.J. Donoghue. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Robert J. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

Full Issue 114

South African Journal of Science volume 114 number 5/6 Decolonising engineering in South Africa The Grootfontein aquifer: Governance of a hydro-social system Household food waste disposal in South Africa South African behavioural ecology research in a global perspective Volume 114 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Number 5/6 John Butler-Adam Academy of Science of South Africa May/June 2018 MANAGING EDITOR Linda Fick Academy of Science of South Africa South African ONLINE PUBLISHING Journal of Science SYSTEMS ADMINISTRATOR Nadine Wubbeling Academy of Science of South Africa ONLINE PUBLISHING ADMINISTRATOR Sbonga Dlamini eISSN: 1996-7489 Academy of Science of South Africa ASSOCIATE EDITORS Nicolas Beukes Leader Department of Geology, University of Johannesburg The Fourth Industrial Revolution and education John Butler-Adam .................................................................................................................... 1 Chris Chimimba Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria Book Review Towards human development friendly universities Linda Chisholm Merridy Wilson-Strydom .......................................................................................................... 2 Centre for Education Rights and Transformation, University of A new look at Old Fourlegs Johannesburg Brian W. van Wilgen ................................................................................................................. 4 Teresa Coutinho Department of Microbiology and Commentary Plant Pathology, University of Pretoria Decolonising -

Mammal and Plant Localities of the Fort Union, Willwood, and Iktman Formations, Southern Bighorn Basin* Wyoming

Distribution and Stratigraphip Correlation of Upper:UB_ • Ju Paleocene and Lower Eocene Fossil Mammal and Plant Localities of the Fort Union, Willwood, and Iktman Formations, Southern Bighorn Basin* Wyoming U,S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESS IONAL PAPER 1540 Cover. A member of the American Museum of Natural History 1896 expedition enter ing the badlands of the Willwood Formation on Dorsey Creek, Wyoming, near what is now U.S. Geological Survey fossil vertebrate locality D1691 (Wardel Reservoir quadran gle). View to the southwest. Photograph by Walter Granger, courtesy of the Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History, New York, negative no. 35957. DISTRIBUTION AND STRATIGRAPHIC CORRELATION OF UPPER PALEOCENE AND LOWER EOCENE FOSSIL MAMMAL AND PLANT LOCALITIES OF THE FORT UNION, WILLWOOD, AND TATMAN FORMATIONS, SOUTHERN BIGHORN BASIN, WYOMING Upper part of the Will wood Formation on East Ridge, Middle Fork of Fifteenmile Creek, southern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. The Kirwin intrusive complex of the Absaroka Range is in the background. View to the west. Distribution and Stratigraphic Correlation of Upper Paleocene and Lower Eocene Fossil Mammal and Plant Localities of the Fort Union, Willwood, and Tatman Formations, Southern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming By Thomas M. Down, Kenneth D. Rose, Elwyn L. Simons, and Scott L. Wing U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1540 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Robert M. Hirsch, Acting Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Map Distribution Box 25286, MS 306, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S.