The Cognitive Advantages of Counting Specifically: an Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polynesian Case

Lexicostatistics Compared with Shared Innovations: the Polynesian Case jK=dÉääJj~ååI=fK=mÉáêçëI=pK=pí~êçëíáå Santa Fe Institute The Polynesian languages, together with Fijian and Rotuman, consti- tute the Central Oceanic branch, which is usually included in a bigger Oceanic family, part of Austronesian. The Polynesian language family consists of 28 languages ([BIGGS 98]) most of which are fairly well known. The history of the family is also well investigated: we have the phonological reconstruction of its protolan- guage ([BIGGS 98], [MARCK 2000]), suggestions about morphology and syntax ([WILSON 982]; [CLARK 96]), and a detailed comparative diction- ary of the family — probably one of the best etymological dictionaries for languages outside Eurasia ([BIGGS n.d.]) The Proto-Polynesian consonantal system is reconstructed as ([BIGGS 98: 08–09]): *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l *r *k *ŋ (*h) `*ʔ Using the principle of «irreversible changes», one can see that the systems of daughter languages could be derived from Proto-Polynesian through a sequence of simple innovations (mostly mergers): . Proto-Tongan: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *r > *k *ŋ *h *ʔ .. Tongan p m f w t n h l k ŋ ʔ 2. Proto-Nuclear Polynesian: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l = *r *k *ŋ *h > * GÉää-M~åå, PÉáêçë, S. Sí~êçëíáå. Lexicostatistics & Shared Innovations . 2. Samoa p m f w t n s l *k > ʔ ŋ 2.2. East Polynesian *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *k *ŋ * 2..3. Tahitian p m f v t n h r *k > ʔ *ŋ > ʔ 2. -

Maori & Pasifika Infants and Toddlers

Tangata Pasifika: Sustaining cultural knowledge and language competency for Pacific peoples. Presentation at the Victoria University Autumn Research Seminar, May 2018. Ali Glasgow Faculty of Education Language, culture, identity • A leai se gagana, ona leai lea o sa ta aganu’u, a leai la ta aganu’u ona po lea o le nu’u (Samoan proverb) • If there is no language, then there is no culture, • If there is no culture, then all of the village will be in darkness Presentation outline • My background • Pacific context • Aoteroa New Zealand context – culture, language • Research findings – Vuw Summer Scholarship (2015), TLRI ( Teaching and Learning Research Initiative, 2017). Ali – Kuki Airani – Tongareva Atoll Pacific perspectives • Pacific region located historically, contextually and geographically within Oceania, more particularly in the region of the Southern Pacific referred to as the Polynesian triangle (Ritchie & Ritchie, 1970) • ‘Our sea of islands ( Hau’ofa, 1993) Reclaiming & Reconceptualising Pacific Education • Pacific Education (currently) prioritises the voice and worldview of the outside which amputates our capacity for human agency. Within the Pacific the bulk of what we teach and learn in our schools and at our universities and colleges in the Pacific is what has been conceptualised and developed in and for the Western world (Koya-Vakauta,2016). • The indigenous peoples of the Pacific need to create their own pedagogy... rooted in Pacific values, assumptions, processes and practices ( Glasgow, 2010; Mara, Foliaki & Coxon, 1994; Tangatapoto,1984 & Taufe’ulungake, 2001). Aspiration Statement ( MOE, 2017, p.5) • Competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society. -

Laulōtaha; Tongan Perspectives of 'Quality' in Early Childhood Education Dorothy Lorraine Pau'uvale a Thesis Submitted To

Laulōtaha; Tongan Perspectives of ‘Quality’ in Early Childhood Education Dorothy Lorraine Pau’uvale A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of Master of Education (MEd) 2011 School of Education i Table of Contents List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... vi Attestation of Authorship .................................................................................................. vii Fakamālō/ Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ viii Ethical Approval .............................................................................................................. xiii Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Talateu/ Introduction ......................................................................................... 2 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Purpose of the study .................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Context of the study .................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Importance of the study ........................................................................................... -

Celebration of the Niuean Language and Culture Ko E Tau Fakafiafiaaga

Celebration of the #pacificstars Niuean Language and Culture Ko e tau Fakafiafiaaga he Vagahau Niue mo e tau Aga Fakamotu Facts on Niue | Folafolaaga hagaaoia Population | Puke tagata ke he motu ko Niue In 2013 Niue peoples were the fourth largest Pacific • Niue is one of the world's largest coral islands. ethnic group in New Zealand making up 8.1% or 23,883 • Niue (pronounced “New-e (‘e’ as in ‘end’ – which means of New Zealand’s Pacific peoples’ population. 'behold the coconut') may be the world’s smallest The most common region this group lived in was the independent nation. Auckland Region (77.7 percent or 18,555 people), followed • The island is commonly referred to as "The Rock", by the Wellington Region (6.6 percent or 1,575 people), a reference to Niue being one of the biggest raised and the Waikato Region (4.3 percent or 1,038 people). coral islands in the world. The median age was 20.4 years. • The capital of Niuē is the village of Alofi. • Niueans are citizens of New Zealand. 78.9 percent (18,465 people) were born in New Zealand. • Niue is an elevated coral atoll with fringing coral reefs encircling steep limestone cliffs. It has a landmass of 259km and its highest point is about 60 metres In 2013 Niue peoples made up above sea level. • Niue lies 2400 km northeast of New Zealand 23,883 between Tonga, Samoa and the Cook Islands. of New Zealand's Pacific peoples' population History | Tau Tala Tu Fakaholo Polynesians from Samoa settled Niue around 900 AD. -

Gender & Interaction in a Globalizing World: Negotiating the Gendered

Chapter 13 Gender and interaction in a globalizing world: Negotiating the gendered self in Tonga* Niko Besnier 1. Gender and language in microscopic and macroscopic perspectives One of the more important developments in our understanding of the rela- tionship between language and gender in the last couple of decades is the recognition that the gendering of language is semiotically complex. Indeed, linguistic forms and practices do not define “women’s language” and “men’s language”, as earlier researchers argued (e.g., Lakoff 1975), but articulate with a host of social categories and processes that surround gen- der and help construct it. The clearest articulation of this position is Ochs’ (1992) demonstration that gendered linguistic practices are both indexical and indirect. Indexicality captures the insight that features of language (phonological, syntactic, discursive, etc.) “point to”, or suggest, gendered identities, and do not refer to gender in an unequivocal fashion, as linguistic symbols would. In this respect, the relationship between language and gen- der is no different from the relationship between language and any other aspect of socio-cultural identity, as we have known since the early days of sociolinguistics (Labov 1966a). However, the indexical linking of language and gender presents another layer of complexity: linguistic resources are semiotically connected to gender through the mediation of other aspects of the socio-cultural world. For example, features of language and interaction invoke social roles (e.g., mother, CEO, construction work), demeanors (e.g., politeness, authority, or the lack thereof), and activities (e.g., forms of work and play), all of which are in turn indexically associated with gender (see Figure 1). -

Samoan Research Methodology

VolumePacific-Asian 23 | Number Education 21 | 2011 Pacific-Asian Education The Journal of the Pacific Circle Consortium for Education Volume 23, Number 2, 2011 SPECIAL ISSUE Inside (and around) the Pacific Circle: Educational Places, Spaces and Relationships SPECIAL ISSUE EDITORS Eve Coxon The University of Auckland, New Zealand Airini The University of Auckland, New Zealand SPECIAL ISSUE EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Elizabeth Rata The University of Auckland, New Zealand Diane Mara The University of Auckland, New Zealand Carol Mutch The University of Auckland, New Zealand EDITOR Elizabeth Rata, School of Critical Studies in Education, Faculty of Education, The University of Auckland, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] EXECUTIVE EDITORS Airini, The University of Auckland, New Zealand Alexis Siteine, The University of Auckland, New Zealand CONSULTING EDITOR Michael Young, Institute of Education, University of London EDITORIAL BOARD Kerry Kennedy, The Hong Kong Institute of Education, Hong Kong Meesook Kim, Korean Educational Development Institute, South Korea Carol Mutch, Education Review Office, New Zealand Gerald Fry, University of Minnesota, USA Christine Halse, University of Western Sydney, Australia Gary McLean, Texas A & M University, USA Leesa Wheelahan, University of Melbourne, Australia Rob Strathdee, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand Xiaoyu Chen, Peking University, P. R. China Saya Shiraishi, The University of Tokyo, Japan Richard Tinning, University of Queensland, Australia ISSN 1019-8725 Pacific Circle Consortium for Education Publication design and layout: Halcyon Design Ltd, www.halcyondesign.co.nz Published by Pacific Circle Consortium for Education http://pacificcircleconsortium.org/PAEJournal.html Pacific-Asian Education Volume 23, Number 2, 2011 CONTENTS Editorial Eve Coxon 5 Articles Tala Mai Fafo: (Re)Learning from the voices of Pacific women 11 Tanya Wendt Samu Professional development in the Cook Islands: Confronting and challenging 23 Cook Islands early childhood teachers’ understandings of play. -

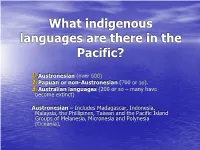

What Languages Are There in the Pacific?

What indigenous languages are there in the Pacific? 1.Austronesian (over 600) 2.Papuan or non-Austronesian (700 or so). 3.Australian languages (200 or so – many have become extinct) Austronesian – Includes Madagascar, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Phillipines, Taiwan and the Pacific Island Groups of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Oceania). Austronesia’s four branches: 1. Western (Non-Oceanic) (about 388 languages, including Malagasy (Madagascar), most of the languages of Indonesia and Malaysia, all Phillipines, the Chamic languages of Vietnam, Palauan (spoken in the western Carolines) and Chamorro (spoken in the Mariana Islands) in Western Micronesia. About 178 million speakers. 2. & 3. Also two smaller branches in Eastern Indonesia and the aboriginal languages of Taiwan. Place of Polynesia 4. Oceanic or Eastern Branch - Includes Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. 2.1 million speakers, 382 languages. Divided into 20+ local groups. Central Pacific Group consists of Polynesian, Fijian, Rotuman. Remaining groups include the languages of New Caledonia, Vanuatu, the Solomons, many languages of coastal New Guinea and its offshore islands, and most of Micronesia. Brief history of the Polynesian languages • Round about 6,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Polynesians - a people we now call Austronesians - moved from South-East Asia, through Melanesia - Papua New Guinea, Solomons, Vanuatu (New Hebrides), to Fiji. • We don't know what these ancestors looked like at that time - probably like Asians with straight black hair, fair skin and oriental eyes. Western Polynesia Once in Fiji, about 3,500 years ago, these people stepped off to the first Polynesian islands - Tonga, Samoa, Niue, and surrounding islands like `Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. -

The Phonemic Reality of Polynesian Vowel Length

The Phonetic Nature of Niuean * Vowel Length Nicholas Rolle University of Toronto In this paper, I argue that in Niuean, long vowels are underlying sequences of two qualitatively identical vowels, extending an analysis laid out in Taumoefolau (2002) on the related Tongic language Tongan. She argues that a long vowel will result predictably when stress falls on the first element of a double monophthong vowel sequence. Thus vowel length in these languages is a phonetic, not phonological, phenomenon. This account for vowel length is worked into an Optimality Theory (OT) framework, which crucially constrains RH- CONTOUR and ALL-FT-RIGHT above a constraint against double articulation, DIST(INCT). In addition, I provide a review of the literature concerning vowel length across Polynesian languages, and conclude that this analysis cannot be extended to all members of the Polynesian language family. 1. Introduction Across Polynesian languages, the presence of long vowels is uncontroversial, though whether these are only surface long vowels (i.e. phonetic) or underlying long vowels (i.e. phonemic) remains a contentious topic. In this paper, I outline an analysis of Tongan long vowels laid out in Taumoefolau (2002), and later supported by Anderson & Otsuka (2006), and extend this analysis to the related Tongic language Niuean. It is argued in Taumoefolau (2002) that Tongan long vowels are underlying identical vowel-vowel sequences (/ViVi/), whose surface manifestation is predictably a long vowel if stress falls on the first vowel of this sequence, and a double articulated vowel if stress falls on the second. This analysis is laid out in detail in section 3, preceded by a section describing some basic facts of Tongan phonology, and a review of the previous analyses of Tongan vowel length. -

Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori O Te Pae Tonga O Te Kuki Airani Also Known As Southern Cook Islands Māori

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. Editors: Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori SALLY AKEVAI NICHOLAS Cite this article: Sally Akevai Nicholas (2018). Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori. In Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne (eds) Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. London: EL Publishing. pp. 36-64 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/160 This electronic version first published: July 2018 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori Sally Akevai Nicholas School of Language & Culture, Auckland University of Technology Language Name: Southern Cook Islands Māori Language Family: East Polynesian, Polynesian, Oceanic, Austronesian ISO 639-3 Code: rar Glottolog Code: raro1241 Number of speakers: ~15,000 - 20,2001 Location: 8-23S, 156-167W Vitality rating: EGIDS between 7 (shifting) and 8a (moribund) 1. -

1 Bilingual Education in Aotearoa/New Zealand Richard Hill

Bilingual education in Aotearoa/New Zealand Richard Hill University of Waikato, New Zealand 1.1 Abstract Bilingual education in the New Zealand context is now over 30 years old. The two main linguistic minority groups involved in this type of education; the Indigenous Māori, and Pasifika peoples, of Samoan, Tongan, Cook Islands, Niuean and Tokelauan backgrounds have made many gains but have struggled in a national context where minority languages have low status. Māori bilingual programs are well established and have made a significant contribution towards reducing Māori language shift that in the 1970s looked to be beyond regeneration. Pasifika bilingual education by contrast is not widely available and not well resourced by the New Zealand government. Both forms continue to need support and a renewed focus at local and national levels. This chapter provides an overview of past development of Māori and Pasifika bilingual education and present progress. For Māori, the issues relate primarily to how to boost language regeneration, particularly between the generations. Gaining greater support for immersion programs and further strengthening bilingual education pedagogies, particularly relating to achieving biliteracy objectives, are key. In the Pasifika context, extending government and local support would not only safeguard the languages, but has the potential to counteract long-established patterns of low Pasifika student achievement in mainstream/English-medium schooling contexts. Finally, the future of both forms of bilingual education can be safeguarded if they are encompassed within a national languages policy that ensures minority language development in the predominantly English monolingual national context of New Zealand. 1 1.2 Introduction Aotearoa/New Zealand has two main bilingual education contexts, Māori and Pasifika.1 Both forms involve minority groups; the Māori language is the Indigenous language of Aotearoa/New Zealand, while the languages of the Pasifika people were brought to this country from the islands of Polynesia from the 1960s onwards. -

Pe Structure Cf Tongan Dance a Dissertation

(UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY P E STRUCTURE CF TONGAN DANCE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION CF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FUIFILDffiNT CF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE CF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ANTHROPOLOGY JUNE 1967 By _\G Adrienne L? Kaeppler Dissertation Committee: Alan Howard, Chairman Thomas W. Maretzki Roland W. Force Harold E. McCarthy Barbara B. Smith PREFACE One of the most conspicious features of Polynesian life and one that has continually drawn comments from explorers, missionaries, travelers, and anthropologists is the dance. These comments have ranged from outright condemnation, to enthusiastic appreciation. Seldom, however, has there been any attempt to understand or interpret dance in the total social context of the culture. Nor has there been any attempt to see dance as the people themselves see it or to delineate the structure of dance itself. Yet dance has the same features as any artifact and can thus be analyzed with regard both to its form and function. Anthropologists are cognizant of the fact that dance serves social functions, for example, Waterman (1962, p. 50) tells us that the role of the dance is the "revalidation and reaffirmation of the aesthetic, religious, and social values shared by a human society . the dance serves as a force for social cohesion and as a means to achieve the cultural continuity without which no human community can persist.” However, this has yet to be scientifically demonstrated for any Pacific Island society. In most general ethnographies dance has been passed off with remarks such as "various movements of the hands were used," or "they performed war dances." In short, systematic study or even satisfactory description of dance in the Pacific has been virtually neglected despite the significance of dance in the social relations of most island cultures. -

The Early LDS Missionaries: Teaching English and Converting Tongans.” by Haitelenisia Uhila I Am Indeed Humbled and Yet Honored to Be Here

The Early LDS Missionaries: Teaching English and Converting Tongans.” by Haitelenisia Uhila I am indeed humbled and yet honored to be here. I aim to teach English to my people someday, but I still struggle with the language because it is my second language. Anyway, I heard of this effort that the Tongan history people (‘Uho o Tonga) are doing and they’re trying to read the journals of the missionaries from Tonga and produce papers out of it, and my thought was, “I want to write something about my people,” Then I asked myself the question, “How were these LDS missionaries from the U.S. mainland, who spoke very little Tongan, able to teach Tongans English, a language which they knew very little or maybe nothing at all about and also how it influenced their conversion to the church, thus the topic of my presentation “The Early LDS Missionaries: Teaching English and Converting Tongans.” Before I go on I would like to read a story that was published in the Church News in 1959 that basically touches on all the things I want to talk about in my presentation—using one vehicle to get to another: Elder James R. Walker and Robert A. Smith were tired and hungry. Since morning they had walked from village from village on the Tongan island of Niuafo’ou, distributing tracts and conversing with the people. They had not eaten since leaving the ship that morning and had been unsuccessful in finding a place to spend the night. “You had better go to another village,” they had been told.