Bio-Queening and Body Art: an Autoethnographic Investigation Into Hybrid Performance Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fatima Mechtab, There Is Only One Remedy: More Mocktails!

MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 Photo by Chris Teel - christeel.ca My Gay Toronto page: 1 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 2 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 3 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 4 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 Alaska Thunderfuck and Bianca Del Rio werq the queens who Werq the World RAYMOND HELKIO Queens Werq the World is coming to the Danforth Music Hall on Friday May 26, 2017. Get your tickets early because a show this epic only comes around once in a while. Alaska Thunderfuck, Alys- sa Edwards, Detox, Latrice Royale and Shangela, plus from season nine of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Aja, Peppermint, Sasha Velour and Trinity Taylor. Shangela recently told Gay Times Magazine “This is the most outrageous and talented collection of queens that have ever toured together. We’re calling this the Werq the World tour because that’s exactly what these Drag Race stars will be doing for fans: Werqing like they’ve never Werqued it before!” I caught up with Alaska and Bianca to get the dish on the upcoming show and the state of drag. My Gay Toronto page: 5 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 What is the most loving thing you’ve ever seen another contestant on RDR do? Alaska: Well I do have to say, when I saw Bianca hand over her extra waist cincher to Adore, I was very mesmerized by the compassion of one queen helping out another, and Drag Race is such a competitive competition and you always want the upper hand, I think that was so mething so genuine and special. -

Voegelin's History of Political Ideas and the Problem of Christian Order

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Voegelin's History of Political Ideas and the problem of Christian order: a critical appraisal Jeffrey Charles Herndon Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Herndon, Jeffrey Charles, "Voegelin's History of Political Ideas and the problem of Christian order: a critical appraisal" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2487. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2487 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. VOEGELIN’S HISTORY OF POLITICAL IDEAS AND THE PROBLEM OF CHRISTIAN ORDER: A CRITICAL APPRAISAL A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of Political Science By Jeffrey C. Herndon B.A., Southwest Texas State University, 1989 M.A., Southwest Texas State University, 1993 May 2003 Acknowledgements Contrary to the mythology of authorship, the writing of a book is really a collective enterprise. While invariably the names of one or two people appear on the title page, my own experience leads me to believe that no book would ever be finished without the help, love, support, and some degree of gentle authoritarianism on the part of those prodding the author forward in his or her work. -

Drag Artist Interviews, 2019

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Southern Illinois University Edwardsville SPARK SIUE Faculty Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity 2020 Drag Artist Interviews, 2019 Ezra Temko [email protected] Adam Loesch SIUE, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://spark.siue.edu/siue_fac Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Temko, Ezra, Adam Loesch, et al. 2020. “Drag Artist Interviews, 2019.” Sociology of Drag, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Spring. Available URL (http://www.ezratemko.com/drag/interviewtranscripts/). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SPARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in SIUE Faculty Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of SPARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Drag Artist Interviews, 2019 To cite this dataset as a whole, the following reference is recommended: Temko, Ezra, Adam Loesch, et al. 2020. “Drag Artist Interviews, 2019.” Sociology of Drag, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Spring. Available URL (http://www.ezratemko.com/drag/interviewtranscripts/). To cite individual interviews, see the recommended reference(s) at the top of the particular transcript(s). Interview -

From Sissy to Sickening: the Indexical Landscape of /S/ in Soma, San Francisco

From sissy to sickening: the indexical landscape of /s/ in SoMa, San Francisco Jeremy Calder University of Colorado, Boulder [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper explores the relation between the linguistic and the visual in communicating social meaning and performing gender, focusing on fronted /s/ among a community of drag queens in SoMa, San Francisco. I argue that as orders of indexicality (Silverstein 2003) are established, linguistic features like fronted /s/ become linked with visual bodies. These body-language links can impose top-down restrictions on the uptake of gender performances. Non-normatively gendered individuals like the SoMa queens embody cross-modal figures of personhood (see Agha 2003; Agha 2004) like the fierce queen that forge higher indexical orders and widen the range of performative agency. KEY WORDS: Indexicality, performativity, queer linguistics, gender, drag queens 1 Introduction This paper explores the relation between the linguistic and the visual in communicating social meaning. Specifically, I analyze the roles language and the body play in gender performances (see Butler 1990) among a community of drag queens and queer performance artists in the SoMa neighborhood of San Francisco, California, and what these gender performances illuminate about the ideological connections between language, body, and gender performativity more generally. I focus on fronted /s/, i.e. the articulation of /s/ forward in the mouth, which results in a higher acoustic frequency and has been shown to be ideologically -

The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau's Political Thought

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Arcadian Exile: The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau’s Political Thought A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Politics School of Arts and Sciences of the Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Joshua James Bowman Washington, D.C. 2016 Arcadian Exile: The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau’s Political Thought Joshua James Bowman, Ph.D. Director: Claes G. Ryn, Ph.D. Henry David Thoreau‘s writings have achieved a unique status in the history of American literature. His ideas influenced the likes of Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., and play a significant role in American environmentalism. Despite this influence his larger political vision is often used for purposes he knew nothing about or could not have anticipated. The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze Thoreau’s work and legacy by elucidating a key tension within Thoreau's imagination. Instead of placing Thoreau in a pre-conceived category or worldview, the focus on imagination allows a more incisive reflection on moral and spiritual questions and makes possible a deeper investigation of Thoreau’s sense of reality. Drawing primarily on the work of Claes Ryn, imagination is here conceived as a form of consciousness that is creative and constitutive of our most basic sense of reality. The imagination both shapes and is shaped by will/desire and is capable of a broad and qualitatively diverse range of intuition which varies depending on one’s orientation of will. -

The State of the Arts in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition The State of the Arts in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mei.edu Cover photos are credited, where necessary, in the body of the collection. 2 The Middle East Institute Viewpoints: The State of the Arts in the Middle East • www.mei.edu Viewpoints Special Edition The State of the Arts in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Viewpoints: The State of the Arts in the Middle East • www.mei.edu 3 Also in this series.. -

An Exploration of Gender, Sexuality and Queerness in Cis- Female Drag Queen Performance

School of Media, Culture & Creative Arts Faux Queens: an exploration of gender, sexuality and queerness in cis- female drag queen performance. Jamie Lee Coull This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University November 2015 DECLARATION To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Human Ethics The research presented and reported in this thesis was conducted in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007) – updated March 2014. The proposed research study received human research ethics approval from the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (EC00262), Approval Number #MCCA-12-12. Signature: Date: 20/11/2015 i ABSTRACT This PhD thesis investigates the cultural implications of cis-women performing female drag, with particular focus on cis-female drag queens (aka faux queens) who are straight-identified. The research has been completed as creative production and exegesis, and both products address the central research question. In the introductory chapter I contextualise the theatrical history of male-to-female drag beginning with the Ancient Greek stage, and foreground faux queens as the subject of investigation. I also outline the methodology employed, including practice-led research, autoethnography, and in-depth interview, and provide a summary of each chapter and the creative production Agorafaux-pas! - A drag cabaret. The introduction presents the cultural implications of faux queens that are also explored in the chapters and creative production. -

QUEER UTOPIA and REPARATION: RECLAIMING FAILURE, VULNERABILITY, and SHAME in DRAG PERFORMANCE by Rodrigo Peroni Submitted to C

QUEER UTOPIA AND REPARATION: RECLAIMING FAILURE, VULNERABILITY, AND SHAME IN DRAG PERFORMANCE By Rodrigo Peroni Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Gender Studies. Supervisor: Professor Eszter Timár Second Reader: Erzsébet Barát CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 Abstract This thesis discusses the critical and queer utopian potential of two performances by Ongina and Alaska Thunderfuck - two contemporary American drag queens. Based on Ongina’s “Beautiful” lip-sync performance and Alaska Thunderfuck's “Your Makeup Is Terrible” video clip, I argue that the performance of failure, vulnerability, and shame troubles multiculturalist discourses for their perpetuation of the neoliberal and masculinist values of individual success (chapter 1), authentic autonomy (chapter 2), and proud stable identity (chapter 3). While and because these performances defy the drag genre’s conventions and drive us to reconsider the prevalent forms of resistance to heterosexism, they also engender a queer utopian potential that allows the imagining and experiencing of alternative ethics. I rely on José Esteban Muñoz’s concept of disidentification and Eve Sedgwick’s notions of paranoid and reparative reading to propose queer communitarian bondings that are not radical nor durable but more inclusive and self-transformative. By interpreting ugliness as failure, I argue that in uglifying themselves Ongina and Alaska expose the meritocracy of neoliberalism and suggest an ethics based not on aesthetic pleasure but on a reparative appreciation of the awful that queers the very notion of community for not holding on to stable identities nor individual achievements. Drawing on a Levinasian discussion of vulnerability and care, I discuss how Alaska disidentifies with the reality TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race's deployment of vulnerability as relatable authenticity while suggesting an alternative ethics with which to encounter the Other based on witnessing, risk, and ungraspability. -

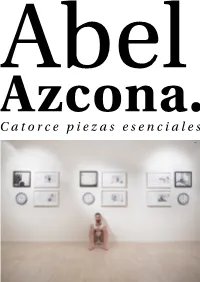

Azcona. Catorce Piezas Esenciales 1 Abel Azcona

Abel Azcona. Catorce piezas esenciales 1 Abel Azcona. Nació el 1 de abril de 1988, fruto de un embarazo no deseado, en la Clínica Montesa de Madrid, institución regentada por una congregación religiosa dirigida a personas en si- tuación de riesgo de exclusión social e indigencia. De padre desconocido, su madre, una joven en ejercicio de la prostitución y politoxicomania llamada Victoria Luján Gutierrez le abandonó en la propia maternidad a los pocos días de nacer. Las religiosas entregaron al recién nacido a un hombre vinculado a su madre, que insistió en su paternidad, a pesar de haber conocido a Victoria ya embarazada y haber sido compañero sentimental esporádico. Azcona se crio desde entonces en la ciudad de Pamplona con la familia de este, igualmente desestructurada y vinculada al narcotráfico y la delincuencia, al estar él entrando y saliendo de prisión de forma continuada. Los primeros cuatro años de vida de Azcona se contextua- lizan en situaciones continuadas de maltrato, abuso y abandono provocadas por diferentes integrantes del nuevo entorno familiar y el paso por varios domicilios, fruto de diferentes retiradas de custodia por instituciones públicas de protección social. El niño se encontraba en situación total de abandono, con signos visibles de abuso, de descuido y de desnutrición, y se aportan testimonios de vecinos y el entorno confirmando que el menor se llega a en- contrar semanas en total soledad en el domicilio, que no cumple las condiciones mínimas de habitabilidad. De los cuatro a los seis años Azcona empieza a ser acogido puntualmente por una familia conservadora navarra que, a los seis años de edad de Azcona, solicitan a instituciones pú- blicas la intervención para convertir la situación en un acogimiento familiar permanente. -

General Editors' Introduction

General Editors’ Introduction PAISLEY CURRAH and SUSAN STRYKER une 2016 saw the US‐based multinational bank Goldman Sachs flying the J pink, white, and blue transgender flag outside its Manhattan headquarters. It saw the United Nations Human Rights Council passing a resolution to appoint an “Independent Expert” to study violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. It saw Pentagon officials announcing the end of the ban on transgender people serving in the US armed forces. No longer occu- pying a position on the margins of civic and economic life, transgender people, it would seem, are increasingly valued as employees, as consumers, as victims in need of saving, and now in the United States, as potential warriors. Valued is right. The recognition of transgender as a source of value, not only for corporations but also for nonprofit sectors that have embraced the rhetoric of the market, has become a popular theme for the ideologues of the current capitalist moment. Whether rescuing trans “victims,” profiting from the creativity of gender‐diverse employees, or carving out new transgender‐specific consumer markets, the neoliberal creed now presents discrimination against trans (and GLB) people as “an enormous waste of human potential, of talent, of cre- ativity, of productivity, that weighs heavily on society and on the economy” (Park 2015: 1). As the head of the largest GLBT advocacy group in the United States explained at the Davos World Economic Forum, “Around the world, businesses have far outpaced lawmakers in embracing the basic premise that the hard work and talents of all their employees—regardless of who they are or whom they love—are rewarded fairly in their workplaces. -

QUEEN LATIFAH Lina Bradford •Rupaul’S Queens•Fayslift April 2017 /May2017

Lina Bradford • RuPaul’s Queens • Fay Slift esented by PinkPlayMags www.thebuzzmag.ca Pr QUEEN LATIFAH For daily and weekly event listings visit Wishes on a Star April 2017 / May 2017 Issue #018 The Editor Greetings and salutations! Publisher + Creative Director: Our cover feature this issue is with Queen Latifah, Antoine Elhashem who currently has a lead role in the new FOX television Editor-in-Chief: series, Star, which has just been renewed for a second Bryen Dunn season and can be seen here in Canada on Netflix. Our Art Director: writer Jerry Nunn chatted with Latifah about her role as Mychol Scully Carlotta Brown, the owner of an Atlanta beauty salon, her General Manager: trans daughter Cotton (played by Amiyah Scott), and the Kim Dobie wonderful wigs she wears. Sales Representatives: Carolyn Burtch, Michael Wile Our second feature is a spotlight on up and coming Kitchener musician, Aylsha Brilla, who’s new album, Events Editor: Sherry Sylvain Humans, has been getting regular play on CBC radio. She Counsel: discusses the challenges of being a female in the male Lai-King Hum, Hum Law Firm dominated music industry, her community work, and her Columnists: love of Amy Winehouse and Bob Marley. Cat Grant skips Fay Slift, Shangela, Paul Bellini, Boyd Kodak, this issue of her She Beat column, and RuPaul protege Raymond Helkio Shangela steps in to tell us all about the upcoming Feature Writers: Queens WERQ The World tour kicking off in Toronto on Jerry Nunn, Bryen Dunn May 26. Cover Photo: Courtesy of FOX Our Wigged Out column this issue is written by Lady- Published by Bear-Extraordinaire, Fay Slift, who is teacher by day and INspired Media Inc. -

Are They Family?: Queer Parents and Queer Pasts In

ARE THEY FAMILY?: QUEER PARENTS AND QUEER PASTS IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CULTURE BY MICHAEL SHETINA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2019 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Siobhan Somerville, Chair Professor Chantal Nadeau Associate Professor Julie Turnock Associate Professor Richard T. Rodríguez, University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT The early twenty-first century saw a marked increase in depictions of LGBTQ people and communities in American popular culture occurring alongside political activism that culminated in the repeal of the Pentagon's Don't Ask, Don't Tell policy (2010) and the Supreme Court's overturning of same-sex marriage bans in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). Even as these events fueled a triumphant progressive narrative in which social and political representation moved LGBTQ people into a better future, a significant strain of LGBTQ-focused popular culture drew its attention to the past. My dissertation, Are They Family?: Queer Parents and Queer Pasts in Popular Culture, examines how American film, television, and literature between 2005 and 2016 construct relationships among LGBTQ people across recent history in generational and familial terms. These works queer the concept of the family by deploying parents and parental figures to examine the role of families in the transmission of queer knowledges, practices, and identities, countering notions of families as mere precursors to queer identity—“families of origin”—or as the agential creations of out LGBTQ people—“families of choice.” These works demonstrate how such dichotomous conceptions of family limit the people, experiences, and forms of affect that are legible within the category of LGBTQ history.