From the Freak Show to Modern Drag - Olivia Germann, Ball State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trixie Mattel and Katya Dating

UNHhhh ep 5: "Dating PART 2" with Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. UNHhhh ep 4: "Dating" with Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. UNHhhh ep 3: "Traveling" w/ Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. UNHhhh ep 2: "RDR8 Cast Advice" w/ Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. 1 day ago · Trixie and Katya are back with new episodes of UNHhhh Season 5 and they've got the trailer to prove it. Here's everything you need to know about Trixie and Katya. Trixie Mattel is the stage name of Brian Firkus, a drag queen, performer, comedian and music artist best known as a Season 7 contestant of RuPaul's Drag Race and the winner of All Stars Following the success she got thanks to the show, Trixie started presenting a web show with Katya, entitled "UNHhhh", on the WOWPresents' YouTube renuzap.podarokideal.ru later starred on their new show entitled . Jul 15, · Katya: Paint on a different one! Trixie Mattel: This is a window for you, Carolyn, to become the new hot girl in the office right under everyone’s noses. Because you watched a few makeup. Mar 27, · Ever since Katya Zamolodchikova returned to Twitter, fans have been anxiously awaiting to see if the drag star would say anything about her friend and former co-star Trixie Mattel’s win on. Mar 24, · — Trixie Mattel (@trixiemattel) December 20, Trixie hasn’t revealed much about her boyfriend. She protects him from social media users as well. Trixie Mattel Net Worth and TV shows. The drag queen, Trixie Mattel has an estimated net worth of $2 million. Trixie started performing drag in the year at LaCage NiteClub. -

Homosexuality and the 1960S Crisis of Masculinity in the Gay Deceivers

Why Don’t You Take Your Dress Off and Fight Like a Man? WHY DON’T YOU TAKE YOUR DRESS OFF AND FIGHT LIKE A MAN?: HOMOSEXUALITY AND THE 1960S CRISIS OF MASCULINITY IN THE GAY DECEIVERS BRIAN W OODMAN University of Kansas During the 1960s, it seemed like everything changed. The youth culture shook up the status quo of the United States with its inves- titure in the counterculture, drugs, and rock and roll. Students turned their universities upside-down with the spirit of protest as they fought for free speech and equality and against the Vietnam War. Many previously ignored groups, such as African Americans and women, stood up for their rights. Radical politics began to challenge the primacy of the staid old national parties. “The Kids” were now in charge, and the traditional social and cultural roles were being challenged. Everything old was old-fashioned, and the future had never seemed more unknown. Nowhere was this spirit of youthful metamorphosis more ob- vious than in the transformation of views of sexuality. In the 1960s sexuality was finally removed from its private closet and cele- brated in the public sphere. Much of the nation latched onto this new feeling of openness and freedom toward sexual expression. In the era of “free love” that characterized the latter part of the decade, many individuals began to explore their own sexuality as well as what it meant to be a traditional man or woman. It is from this historical context that the Hollywood B-movie The Gay Deceivers (1969) emerged. This small exploitation film, directed by Bruce Kessler and written by Jerome Wish, capitalizes on the new view of sexuality in the 1960s with its novel (at least for the times) comedic exploration of homosexu- ality. -

Fatima Mechtab, There Is Only One Remedy: More Mocktails!

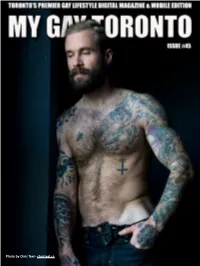

MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 Photo by Chris Teel - christeel.ca My Gay Toronto page: 1 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 2 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 3 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 4 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 Alaska Thunderfuck and Bianca Del Rio werq the queens who Werq the World RAYMOND HELKIO Queens Werq the World is coming to the Danforth Music Hall on Friday May 26, 2017. Get your tickets early because a show this epic only comes around once in a while. Alaska Thunderfuck, Alys- sa Edwards, Detox, Latrice Royale and Shangela, plus from season nine of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Aja, Peppermint, Sasha Velour and Trinity Taylor. Shangela recently told Gay Times Magazine “This is the most outrageous and talented collection of queens that have ever toured together. We’re calling this the Werq the World tour because that’s exactly what these Drag Race stars will be doing for fans: Werqing like they’ve never Werqued it before!” I caught up with Alaska and Bianca to get the dish on the upcoming show and the state of drag. My Gay Toronto page: 5 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 What is the most loving thing you’ve ever seen another contestant on RDR do? Alaska: Well I do have to say, when I saw Bianca hand over her extra waist cincher to Adore, I was very mesmerized by the compassion of one queen helping out another, and Drag Race is such a competitive competition and you always want the upper hand, I think that was so mething so genuine and special. -

MASTERCLASS Meet

MASTERCLASS Meet uPaul Charles’s chameleonic qualities have made him a television icon, spiritual guide, and R the most commercially successful drag queen in United States history. Over a nearly three-decade career, he’s ushered in a new era of visibility for drag, upended gender norms, and highlighted queer talent from across the world—all while dressed as a fierce glamazon. “Be willing to become the shape-shifter that you absolutely are.” Born in San Diego, California, RuPaul first experienced mainstream success when a dance track he wrote called “Supermodel (You Better Work)” became an unexpected MTV hit (Ru stars in the music video). The song led to a modeling contract with MAC Cosmetics and a talk show on VH1, which saw RuPaul interviewing everyone from Nirvana to the Backstreet Boys and Diana Ross to Bea Arthur. He has since appeared in more than three dozen films and TV shows, including Broad City, The Simpsons, But I’m a Cheerleader!, and To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar. RuPaul’s Drag Race, Ru’s decade-old, Emmy-winning reality drag competition, has gone international, with spin-offs set in the U.K. and Thailand. He’s also published three books: 2 RuPaul 1995’s Lettin’ It All Hang Out, 2010’s Workin’ It!, and 2018’s GuRu, which features a foreword from Jane Fonda. Recently, he became the first drag queen to land the cover of Vanity Fair. His Netflix debut, AJ and the Queen, premiered on the streaming service in January 2020. RuPaul saw drag as a tool that would guide his punk rock, anti-establishment ethos. -

Kimmel Center Cultural Campus Presents Critically-Acclaimed Drag Theatre Show Spectacular Sasha Velour's Smoke & Mirrors

Tweet It! Drag icon @Sasha_Velour’s revolutionary show “Smoke & Mirrors” will be at the @KimmelCenter on 11/12. The effortless blend of drag, visual art, and magic is a can’t-miss! More info @ kimmelcenter.org Press Contact: Lauren Woodard Jessica Christopher 215-790-5835 267-765-3738 [email protected] [email protected] KIMMEL CENTER CULTURAL CAMPUS PRESENTS CRITICALLY-ACCLAIMED DRAG THEATRE SHOW SPECTACULAR SASHA VELOUR’S SMOKE & MIRRORS, COMING TO THE MERRIAM THEATER NOVEMBER 12, 2019 "Smoke & Mirrors is a spellbinding tour de force." - Forbes “The intensely personal [Smoke & Mirrors] shows what a top-of-her-game queen Velour really is, both as an artist and as a storyteller.” - Paper Magazine "[Velour’s] most spectacular stage gambit yet." - Time Out New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, October 9, 2019) – Sasha Velour’s Smoke & Mirrors, the critically-acclaimed one-queen show by global drag superstar and theatre producer, Sasha Velour, will come to the Kimmel Center Cultural Campus’ Merriam Theater on November 12, 2019 at 8:00 p.m., as part of the show’s 23-city North American tour. This is Velour’s first solo tour, following her win of RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 9, and sold-out engagements of Smoke & Mirrors in New York City, Los Angeles, London, Australia, and New Zealand this year. “Sasha Velour is a drag superstar, as well as an astonishing talent in the visual arts,” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Smoke & Mirrors invites audiences to experience the depths of Velour that have yet to be explored in the public eye. -

Sissies by Brandon Hayes ; Claude J

Sissies by Brandon Hayes ; Claude J. Summers Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Sissy as a term for an effeminate male developed from its use as an affectionate variant of "sister"; it then came to be used as a disparaging term for boys who behaved like girls. The American Heritage Dictionary defines sissy as "a boy or man regarded as effeminate." The term is pejorative, and its use as such has powerful effects on male behavior generally. It serves as a kind of social control to enforce "gender appropriate" behavior. Indeed, so strong is its power that, in order to avoid being labeled a sissy, many boys--both those who grow up to be homosexual and those who grow up to be heterosexual--consciously attempt to redirect their interests and inclinations from suspect areas such as, for example, hair styling or the arts toward stereotypically masculine interests such as sports or engineering. In addition, they frequently repress-- sometimes at great cost--aspects of their personalities that might be associated with the feminine. At the root of the stigma attached to sissies is the fear and hatred of homosexuality and, to a lesser extent, of women. Certainly, much of the anxiety aroused by boys who are perceived as sissies is the fear (and expectation) that they will grow up to be homosexuals. The stigmatizing power of the term has had particularly strong repercussions on gay male behavior, as well as on the way that gay men are perceived, both by heterosexuals and by each other. -

Un Reality Para Los Que Entienden Y Los Que No

Un reality para los que entienden y los que no El programa RuPaul’s Drag Race y su contexto lingüístico: la dificultad de traducir el vocabulario drag y los juegos de palabras Arnau Pérez i Sampietro Tutor: Patrick Zabalbeascoa Terran Seminario 204: Traducció audiovisual Curso 2017-2018 Abstract This project aims to show different aspects that should be taken into account when translating a TV show like RuPaul’s Drag Race, a show because of the specific vocabulary of a subculture inside the LGBT minority, and because of its use of puns and sense of humour. As an introduction, a small explanation of what the program is about, its context in the USA society and its current fame are given, as well as a consideration about key aspects to be taken into account before getting into the translation. These include the thought process of deciding whether to use subtitles or dubbing, gender treatment of drag queen contestants, the presence of humour, and humour aspects behind what is said and how to make it possible for a Spanish-speaking person to understand them. After that, a small analysis of existing translations of the show into Spanish is presented. The most important aspect of this study is the translation we propose of different elements of the show. These translations are divided in three categories, including: typical slang used by drag queens on or off the show; specific phraseology that originated or has been popularised by the show; and puns extracted from the show. The translation options are followed by an explanation of the translation process, taking into account the fact that it should be as comprehensible as it is to an English viewer of the show but it also has to make a Spanish viewer laugh as much. -

Drag Artist Interviews, 2019

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Southern Illinois University Edwardsville SPARK SIUE Faculty Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity 2020 Drag Artist Interviews, 2019 Ezra Temko [email protected] Adam Loesch SIUE, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://spark.siue.edu/siue_fac Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Temko, Ezra, Adam Loesch, et al. 2020. “Drag Artist Interviews, 2019.” Sociology of Drag, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Spring. Available URL (http://www.ezratemko.com/drag/interviewtranscripts/). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SPARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in SIUE Faculty Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of SPARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Drag Artist Interviews, 2019 To cite this dataset as a whole, the following reference is recommended: Temko, Ezra, Adam Loesch, et al. 2020. “Drag Artist Interviews, 2019.” Sociology of Drag, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Spring. Available URL (http://www.ezratemko.com/drag/interviewtranscripts/). To cite individual interviews, see the recommended reference(s) at the top of the particular transcript(s). Interview -

A Look at 'Fishy Drag' and Androgynous Fashion: Exploring the Border

This is a repository copy of A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/121041/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Willson, JM orcid.org/0000-0002-1988-1683 and McCartney, N (2017) A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty, 8 (1). pp. 99-122. ISSN 2040-4417 https://doi.org/10.1386/csfb.8.1.99_1 (c) 2017, Intellect Ltd. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 JACKI WILLSON University of Leeds NICOLA McCARTNEY University of the Arts, London and University of London A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman Abstract This article seeks to re-explore and critique the current trend of androgyny in fashion and popular culture and the potential it may hold for gender deviant dress and politics. -

Rupaul's Drag Race All Stars Season 2

Media Release: Wednesday August 24, 2016 RUPAUL’S DRAG RACE ALL STARS SEASON 2 TO AIR EXPRESS FROM THE US ON FOXTEL’S ARENA Premieres Friday, August 26 at 8.30pm Hot off the heels of one of the most electrifying seasons of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Mama Ru will return to the runway for RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars Season 2 and, in a win for viewers, Foxtel has announced it will be airing express from the US from Friday, August 26 at 8.30pm on a new channel - Arena. In this second All Stars instalment, YouTube sensation Todrick Hall joins Carson Kressley and Michelle Visage on the judging panel alongside RuPaul for a season packed with more eleganza, wigtastic challenges and twists than Drag Race has ever seen. The series will also feature some of RuPaul’s favourite celebrities as guest judges, including Raven- Symone, Ross Matthews, Jeremy Scott, Nicole Schedrzinger, Graham Norton and Aubrey Plaza. Foxtel’s Head of Channels, Stephen Baldwin commented: “We know how passionate RuPaul fans are. Foxtel has been working closely with the production company, World of Wonder, and Passion Distribution and we are thrilled they have made it possible for the series to air in Australia just hours after its US telecast.” RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars Season 2 will see 10 of the most celebrated competitors vying for a second chance to enter Drag Race history, and will be filled with plenty of heated competition, lip- syncing for the legacy and, of course, the All-Stars Snatch Game. The All Stars queens hoping to earn their place among Drag Race Royalty are: Adore Delano (S6), Alaska (S5), Alyssa Edwards (S5), Coco Montrese (S5), Detox (S5), Ginger Minj (S7), Katya (S7), Phi Phi O’Hara (S4), Roxxxy Andrews (S5) and Tatianna (S2). -

THE TUFTS DAILY Tufts Dining Workers and Students Are Pictured Marching in the ‘Picket for a Fair Dining Contract’ on March 5

WOMEN’S LACROSSE Work-study students discuss pressures, commitments see FEATURES / PAGE 4 Jumbos put on offensive clinic in win over Continentals A call for trustee transparency SEE SPORTS/BACK PAGE see OPINION/ PAGE 10 THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF TUFTS UNIVERSITY EST. 1980 HE UFTS AILY VOLUME LXXVII, ISSUE 30T T D MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, MASS. WEDNESDAY, MARCH 6, 2019 tuftsdaily.com More than 800 people attend picket for dining workers, strike vote set for March 14 KYLE LUI / THE TUFTS DAILY Tufts Dining workers and students are pictured marching in the ‘Picket for a Fair Dining Contract’ on March 5. by Alexander Thompson “Tufts University can afford for one job He said the university hopes to resolve the situ- Trisha O’Brien, a dining services atten- Assistant News Editor to be enough for all workers. It was never ation as soon as possible. dant at Kindlevan Café who held the banner a question of affordability, it’s a question of The dining workers first began their negoti- at the head of the procession as it moved to In a dramatic development in their sev- respect for human dignity,” Lang told the ations with Tufts in August 2018. Dewick-MacPhie Dining Center, said that she en-month campaign for a contract with crowd through a megaphone. “This admin- In an email to the Daily after the latest would vote for the the strike because she the university, Tufts Dining workers will istration is getting increasingly isolated on round of negotiations on Feb. 27, Mike Kramer, thinks negotiations are not going well, and a vote on whether to go on strike on March this campus and in the communities around the lead negotiator for UNITE HERE Local 26, strike is necessary in order for the workers to 14, according to UNITE HERE Local 26 this campus.” wrote that the sticking points were key eco- secure a fair contract. -

From Sissy to Sickening: the Indexical Landscape of /S/ in Soma, San Francisco

From sissy to sickening: the indexical landscape of /s/ in SoMa, San Francisco Jeremy Calder University of Colorado, Boulder [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper explores the relation between the linguistic and the visual in communicating social meaning and performing gender, focusing on fronted /s/ among a community of drag queens in SoMa, San Francisco. I argue that as orders of indexicality (Silverstein 2003) are established, linguistic features like fronted /s/ become linked with visual bodies. These body-language links can impose top-down restrictions on the uptake of gender performances. Non-normatively gendered individuals like the SoMa queens embody cross-modal figures of personhood (see Agha 2003; Agha 2004) like the fierce queen that forge higher indexical orders and widen the range of performative agency. KEY WORDS: Indexicality, performativity, queer linguistics, gender, drag queens 1 Introduction This paper explores the relation between the linguistic and the visual in communicating social meaning. Specifically, I analyze the roles language and the body play in gender performances (see Butler 1990) among a community of drag queens and queer performance artists in the SoMa neighborhood of San Francisco, California, and what these gender performances illuminate about the ideological connections between language, body, and gender performativity more generally. I focus on fronted /s/, i.e. the articulation of /s/ forward in the mouth, which results in a higher acoustic frequency and has been shown to be ideologically