Arabic Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

You May View It Or Download a .Pdf Here

“I put my trust in God” (“Tawakkaltu ‘ala ’illah”) Word 2012 —Arabic calligraphy in nasta’liq script on an ivy leaf 42976araD1R1.indd 1 11/1/11 11:37 PM Geometry of the Spirit WRITTEN BY DAVID JAMES alligraphy is without doubt the most original con- As well, there were regional varieties. From Kufic, Islamic few are the buildings that lack Hijazi tribution of Islam to the visual arts. For Muslim cal- Spain and North Africa developed andalusi and maghribi, calligraphy as ornament. Usu- Cligraphers, the act of writing—particularly the act of respectively. Iran and Ottoman Turkey both produced varie- ally these inscriptions were writing the Qur’an—is primarily a religious experience. Most ties of scripts, and these gained acceptance far beyond their first written on paper and then western non-Muslims, on the other hand, appreciate the line, places of origin. Perhaps the most important was nasta‘liq, transferred to ceramic tiles for Kufic form, flow and shape of the Arabic words. Many recognize which was developed in 15th-century Iran and reached a firing and glazing, or they were that what they see is more than a display of skill: Calligraphy zenith of perfection in the 16th century. Unlike all earlier copied onto stone and carved is a geometry of the spirit. hands, nasta‘liq was devised to write Persian, not Arabic. by masons. In Turkey and Per- The sacred nature of the Qur’an as the revealed word of In the 19th century, during the Qajar Dynasty, Iranian sia they were often signed by Maghribıi God gave initial impetus to the great creative outburst of cal- calligraphers developed from nasta‘liq the highly ornamental the master, but in most other ligraphy that began at the start of the Islamic era in the sev- shikastah, in which the script became incredibly complex, con- places we rarely know who enth century CE and has continued to the present. -

Abstracts Electronic Edition

Societas Iranologica Europaea Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the State Hermitage Museum Russian Academy of Sciences Abstracts Electronic Edition Saint-Petersburg 2015 http://ecis8.orientalstudies.ru/ Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts CONTENTS 1. Abstracts alphabeticized by author(s) 3 A 3 B 12 C 20 D 26 E 28 F 30 G 33 H 40 I 45 J 48 K 50 L 64 M 68 N 84 O 87 P 89 R 95 S 103 T 115 V 120 W 125 Y 126 Z 130 2. Descriptions of special panels 134 3. Grouping according to timeframe, field, geographical region and special panels 138 Old Iranian 138 Middle Iranian 139 Classical Middle Ages 141 Pre-modern and Modern Periods 144 Contemporary Studies 146 Special panels 147 4. List of participants of the conference 150 2 Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts Javad Abbasi Saint-Petersburg from the Perspective of Iranian Itineraries in 19th century Iran and Russia had critical and challenging relations in 19th century, well known by war, occupation and interfere from Russian side. Meantime 19th century was the era of Iranian’s involvement in European modernism and their curiosity for exploring new world. Consequently many Iranians, as official agents or explorers, traveled to Europe and Russia, including San Petersburg. Writing their itineraries, these travelers left behind a wealthy literature about their observations and considerations. San Petersburg, as the capital city of Russian Empire and also as a desirable station for travelers, was one of the most important destination for these itinerary writers. The focus of present paper is on the descriptions of these travelers about the features of San Petersburg in a comparative perspective. -

ISLAMIC and INDIAN ART Tuesday 18 October 2016

ISLAMIC AND INDIAN ART Tuesday 18 October 2016 ISLAMIC AND INDIAN ART Tuesday 18 October 2016 at 11am 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING Live online bidding is available CUSTOMER SERVICES ILLUSTRATIONS Sunday 16 October 11am to 3pm for this sale Monday to Friday Front cover: lot 11 (detail) Monday 17 October 9am to 4.30pm Please email [email protected] 8.30am to 6pm Back cover: lot 101 with ‘live bidding’ in the subject +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Inside front cover: lot 302 (detail) Inside back cover: lot 128 (detail) SALE NUMBER line 48 hours before the auction 23437 to register for this service As a courtesy to intending bidders, Bonhams will provide a IMPORTANT INFORMATION CATALOGUE Please note: written Indication of the physical £30.00 Telephone bidding is available only condition of lots in this sale if a In February 2014 the United on lots where the lower end request is received up to 24 States Government estimate is at £1000 or above. hours before the auction starts. announced the intention to BIDS This written Indication is issued ban the import of any ivory +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 ENQUIRIES subject to Clause 3 of the Notice into the USA. Lots +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Oliver White to Bidders. containing ivory are To bid via the internet please (Head of Department) indicated by the symbol Ф visit bonhams.com +44 207 468 8303 printed beside the Lot [email protected] number in this catalogue. Please note that bids should be submitted no later than 4pm on Matthew Thomas the day prior to the sale. -

Arabic Type Classification System

ARABIC TYPE CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM QUALITATIVE CLASSIFICATION OF HISTORIC ARABIC WRITING SCRIPTS IN THE CONTEMPORARY TYPOGRAPHIC CONTEXT BY DARIN ABU-SHAQRA | INCLUSIVE DESIGN | 2020 SUBMITTED TO OCAD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DESIGN IN INCLUSIVE DESIGN TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA, 2020 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere appreciation to both my primary advisor Richard Hunt, and secondary advisor Peter Coppin, your unlimited positivity, guidance and support was crucial to the comple- tion of this work. It was an absolute honour to have two geniuses in their fields as my advisors. Enriching my knowledge of typography and graphic design and looking through the lens of inclusive design and cognitive science of representation shaped a new respect for the cultural and experiential power of typography in me. My sincere gratitude goes to the talented calligraphers and graphic designers whom I have interviewed back in Jordan. Thank you, for your valuable time, and for allowing me to watch the world from different angles, and experiences. This project owes a lot to your motivation. My heartfelt thanks goes to my family - my late father Khalid, who, although is no longer with me, continues to inspire every step I have to take, my mother Nadia for being the symbol of strength and persistence, my siblings Yasmin, Omar, Ali and Abdullah for always believing in my dreams and doing whatever it takes to make them come true. A special thanks goes to the one who made those two years possible, Ra’ad thank you for being the definition of a life companion and a husband. -

Iranian Contribution to the Art of Islamic Calligraphy

Electronic Articles Collections Prof. Dr. Amir H. Zekrgoo ZEKRGOO.COM Zekrgoo, Amir H. (1991). “Iranian’s Contribution to the Art of Islamic Calligraphy”, Journal of the Indian Museums. New Delhi: Museum Association of India, pp. 62-71. Iranian Contribution to the Art of Islamic Calligraphy The art of Islamic Calligraphy is considered to be one of the highest forms of artistic expression in the entire Muslim world. In view of its widespread use even-to-day, only second to the Roman Alphabet, the Arabic script which is the mother of all Islamic scripts, was developed at a much later date. If we compare the kind of script used by the nomadic Arabs of Hijaz before the appearance of Islam with the great progress it made in the wake of Islam and the revelation of the Holy Quran we discern on it the tremendous influence of Islam—the discipline, beauty and elegance which it lent to this script. A comparison of the two inscriptions written in Nabataean script (The Pre-Islamic script of Arabs) fig. I & 2 first dated 250 A.D. and the second dated 568 A.D. will reveal how little change has taken place in course of about 300 years until the birth of Islam. Immediately after the advent of Islam we witness the invention of the Kufic script. Unlike the primitive Nabataean script, the Kufic, an early Islamic script has a strong geometrical structure (Fig. 3). It has based mainly on long horizontal and short vertical lines with very minor curves. The Kufic later developed into various decorative styles. -

Calligraphy Background • the Divine Revelations to Prophet Muhammad Are Compiled Into a Manuscript: the Quran

Arabic Calligraphy Background • The divine revelations to Prophet Muhammad are compiled into a manuscript: The Quran. Since it is Islam's holiest book, copying the text is considered an art of devotion. • Calligraphy appears on both religious and secular objects in almost every medium- architecture, paper, ceramics, carpets, glass, jewelry, woodcarving, and metalwork. • The need to transcribe the Quran resulted in formalization and embellishing of Arabic writing. • Before the invention of the printing press, everything had to be written by hand • Master calligraphers had a higher status than painters in Muslim lands. • What sort of artists/entertainers have the highest status in our world today? Turn & talk with a partner Materials and Process Training was a long and rigorous process. The calligrapher traditionally prepares their own special tools. Pens (Qalam) were fastened out of hollow reeds for their flexibility. Inks were prepared using natural materials such as soot, ox gall, gum arabic, or plant essences. Manuscripts were written on papyrus and parchment from animal skin before paper was introduced. Families • In medieval Persia, calligraphers were the most highly regarded artists. The art was often passed down within the same family. • What is something that has been passed down within your family? Turn and talk with a partner • The type of script used is Scripts determined by a number of factors such as the audience, content, and function. • The first script to gain prominence in Qurans and in architecture was kufic. It features angular letters, a horizontal format, and thick extended strokes. Proportions • From the 10th to the 13th century, a new system of proportional cursive scripts, that were codified, emerged. -

Islamic Calligraphy: Round and Rectilinear Script

Running Head: ISLAMIC CALLIGRAPHY: ROUND AND RECTILINEAR SCRIPT Islamic Calligraphy: A Comparison between Round and Rectilinear Script Noor Danielle Murteza U14121079 Cultural Studies University of Sharjah – CFAD - Running Head: ISLAMIC CALLIGRAPHY: ROUND AND RECTILINEAR SCRIPT Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 3 CLASSIFICATION RESEARCH ............................................................................................................ 3 RECTILINEAR AND ROUNDED STYLES ............................................................................................... 4 Rectilinear. ................................................................................................................................................ 4 RECTILINEAR AND ISLAMIC CALLIGRAPHY ................................................................................ 5 Rounded. ................................................................................................................................................... 6 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Running Head: ISLAMIC CALLIGRAPHY: ROUND AND RECTILINEAR SCRIPT INTRODUCTION Rectilinear and rounded are two classifications for Islamic calligraphy. They have been the subject of numerous academic studies and publications1 that seek to describe their origins, how -

Origination, Development and the Types of Islamic Calligraphy (Khatt Writing) Amjad Parvez*

AL-ADWA 50:33 1 Origination, Development and the Type of Islamic Calligraphy (Khatt Writing) Origination, Development and the Types of Islamic Calligraphy (Khatt Writing) Amjad Parvez* Origination and Development of Islamic Calligraphy: Like Islamic history, calligraphic history too is very old and Muslim artists are researching on Islamic writing. In the initial phase of Islamic epoch, two kinds of the script emerged that have been in fashion, both the scripts were derived from the different shapes that the Nabataean alphabets were being written in. Out of these two styles, one was Kufic1. It was square in its basic form with pointed or angular finishing. This style was used for the first time for the handwritten copies of the Holy Quran. Later, the same script style was used for the beautification of architecture erected by the earlier Islamic Empires. The other type of script that was cursive and circular in form was known as Naskhi. This style of script was more prevalent in official or business documents and letters, because of its free flowing technique and quick to write facility. Naskhi, in the Kufic style of the second century Hijri, was then limited only to special uses, except for the northwest Africa, where it was evolvedd into the Maghribi style of script2. On the other hand, the rounded style script Naskhi remained in use all the times. From this Naskhi mostly later styles of Arabic writing have been developed. “Khatt-e-Koofi” that is the advanced form of “Khatt-e- Moakli”. Later, during the Umayyad period3, calligraphy flourished in Damascus and scribes started to introduce alteration in the original heavy and thick style of Kufic style to evolve a form employed in the modern times, especially for ornamental purposes. -

Origination, Development and the Types of Islamic Calligraphy (Khatt

اﻻضواء Al-A ā ISSN 2415-0444; E- ISSN 1995-7904 Volume 50, Issue, 33, 2018 Published by Sheikh Zayed Islamic Centre, University of the Punjab, Lahore, 54590 Pakistan. Origination, Development and the Types of Islamic Calligraphy (Khatt Writing) Amjad Parvez* Abstract: Calligraphy is purely handwriting for recording and conveying information, sometimes observably and at times not, but in most cases quickly with fewer concerns to its appearance. The brilliance of Islamic writing lies in its infinite creativeness and versatility. The sense of balance, created and executed by calligraphers, is not only for transmitting a text but also expressing its significance through a proper aesthetic code. What distinguishes Islamic script from ordinary writing is basically beauty. This article is an effort to revive this beautiful art and investigate its origination, development, and types. Key words: Islamic Calligraphy, Khatt Writing, Islamic history. Origination and Development of Islamic Calligraphy: Like Islamic history, calligraphic history too is very old and Muslim artists are researching on Islamic writing. In the initial phase of Islamic epoch, two kinds of the script emerged that have been in fashion, both the scripts were derived from the different shapes that the Nabataean alphabets were being written in. Out of these two styles, one was Kufic1. It was square in its basic form with pointed or angular finishing. This style was used for the first time for the handwritten copies of the Holy Quran. Later, the same script style was used for the beautification of architecture erected by the earlier Islamic Empires. The other type of script that was cursive and circular in form was known as Naskhi. -

Visual Codifications of the Qur'an Between 1000 and 1700

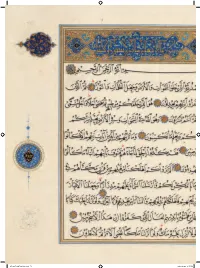

076-097 224720 CS6.indd 76 2016-09-02 1:55 PM Shaping the Word of God: Visual Codifications of the Qur’an between 1000 and 1700 ¡¢£¤ ¥¦§§¡¨ Today, a printed copy of the Qur’an looks disnctly unlike any other pe of book wrien in Arabic script.1 e Holy Book of Islam, the Word of God for Muslims, oen is published in a single volume, with a dense display of text on the page and a limited selecon of standardized fonts: naskh for the text, thuluth for the chapter (sura) tles. e modern, mass-produced mushaf (plural: masahif), the Arabic word for a wrien copy of the Qur’an, is a singular book object, unique in sle and format. When Muslims and non-Muslims alike are asked to picre the Qur’an, oen what comes to mind is an austere book, with both text and decorave elements rendered in black and white. Such elements include the opening double-page spread with the first sura on the right and the beginning of the second chapter on the le page. All the subsequent chapter tles are presented in framed and decorated headings (unwan). e text on every page is also enclosed in a simple framing border. roughout the book, inscribed medallions in the margins indicate divisions of the text. Appearing oen, though not always, are numerical markers of the thir-secon divisions (juz; plural: ajza’), and more occasionally their subdivisions: rub‘ (quarter), nisf (half), thalatha arba‘ (three- fourths) as well as the fourteen indicaons of prosaon (sajda). Finally, small, idencal devices inserted in the text separate verses (aya) and present the posion number of the preceding aya. -

Bloom-2001-03.Pdf

Stories which were written had a higher status than those which continued to be transmit PAPER ted orally. Remarkable stories deserved somethingbetter than oral transmission. That the AND BOOKS story is so good that it must be written down is in fact a recurring topos in the [Arabian] Nights: lYour story must be written down in books, and read after you, age after age." Only writingguarantees survival, and "Writing makes the best claim on the attention ofthose who should marvel at or take warning from the stories. - ROB ERT I R WIN, The Arabian Nights Western historians have often argued that Islamic civilization made its greatest mistake in the fifteenth century when it refused to accept the printing press, for this failure supposedly condemned Islamic civilization to isolation from the mainstream of knowledge. Although Muslims did not use the printing press until the eighteenth century, and then only tentatively, they had other means of transmitting knowledge effectively and broadly, and for the preced ing eight centuries the inhabitants ofthe Islamic lands-not only Muslims but Christians andJews as well-controlled the sluicegates ofthe very same stream of knowledge at which thirsty Europeans repeatedly came to drink. Bureaucratic necessity may have led Muslim officials to adopt paper, but the availability of paper in the Islamic lands also encouraged an efflorescence ofbooks and written culture incomparably more brilliant than was known any where in Europe until the invention of printing with movable type in the fifteenth century. In spite of the absence ofprinting in the Islamic lands, the spread of written knowledge there was comparable to-and may have sur passed-the spread of written culture in China after large-scale printing developed there in the tenth century. -

"THE EYE IS FAVORED for SEEING the WRITING's FORM": on the SENSUAL and the SENSUOUS in ISLAMIC CALLIGRAPHY Author(S): DAVID J

"THE EYE IS FAVORED FOR SEEING THE WRITING'S FORM": ON THE SENSUAL AND THE SENSUOUS IN ISLAMIC CALLIGRAPHY Author(s): DAVID J. ROXBURGH Source: Muqarnas, Vol. 25, FRONTIERS OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE: ESSAYS IN CELEBRATION OF OLEG GRABAR'S EIGHTIETH BIRTHDAY (2008), pp. 275-298 Published by: BRILL Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27811125 . Accessed: 22/09/2014 13:46 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. BRILL is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Muqarnas. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Mon, 22 Sep 2014 13:46:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions DAVID J. ROXBURGH "THE EYE IS FAVORED FOR SEEING THE WRITING'S FORM": ON THE SENSUAL AND THE SENSUOUS IN ISLAMIC CALLIGRAPHY is to a carrier of Writing is calliphoric, that say beauty, in figs. 1 and 2) attributed to Firuz Mirza Nusrat al and it becomes terpnopoietic by bringing pleasure... Dawla I is an exception that makes the kinetic and Difficulties as soon as one tries to under arise, however, temporal dimensions of the calligrapher's work evi stand what is or even artistic in actually beauty quality dent, available to the eye.