PERSIAN PEREGRINATION Miles Lewis 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study the Status Column Element in the Achaemenid Architecture and Its

Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND January 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Study the status column element in the Achaemenid architecture and its effect on India architecture (comparrative research of persepolis columns on pataly putra columns in India) Dr. Amir Akbari* Faculty of History, Bojnourd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bojnourd, Iran * Corresponding Author Fariba Amini Department of Architecture, Bukan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bukan, Iran Elham Jafari Department of Architecture, Khoy Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khoy, Iran Abstract In the southern region of Iran and the north of persian Gulf, the state was located in the ancient times was called "pars", since the beginning of the Islamic era its center was shiraz. In this region of Iran a dynasty called Achaemenid came to power and could govern on the very important part of the worlds for years. Achaemenid exploited the skills of artists and craftsman countries under its command. In this sense, in Architecture works and the industry this period is been seen the influence of other nations. Achaemenid kings started to build large and beautiful palaces in the unter of their government and after 25 centuries, the remnants of which still remain firm and after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire by Grecian Alexander in India. The greatest king of India dynasty Muryya, was called Ashoka the grands of Chandra Gupta. The Ashoka palace that id located at the putra pataly around panta town in the state of Bihar in North east India. Is an evidence of the influence of Achaemenid culture in ancient India. The similarity of this city and Ashoka Hall with Apadana Hall in Persepolis in such way that has called it a india persepolis set. -

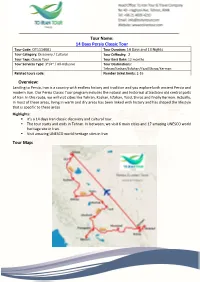

14 Days Persia Classic Tour Overview

Tour Name: 14 Days Persia Classic Tour Tour Code: OT1114001 Tour Duration: 14 Days and 13 Nights Tour Category: Discovery / Cultural Tour Difficulty: 2 Tour Tags: Classic Tour Tour Best Date: 12 months Tour Services Type: 3*/4* / All-inclusive Tour Destinations: Tehran/Kashan/Esfahan/Yazd/Shiraz/Kerman Related tours code: Number ticket limits: 2-16 Overview: Landing to Persia, Iran is a country with endless history and tradition and you explore both ancient Persia and modern Iran. Our Persia Classic Tour program includes the natural and historical attractions old central parts of Iran. In this route, we will visit cities like Tehran, Kashan, Isfahan, Yazd, Shiraz and finally Kerman. Actually, in most of these areas, living in warm and dry areas has been linked with history and has shaped the lifestyle that is specific to these areas. Highlights: . It’s a 14 days Iran classic discovery and cultural tour. The tour starts and ends in Tehran. In between, we visit 6 main cities and 17 amazing UNESCO world heritage site in Iran. Visit amazing UNESCO world heritage sites in Iran Tour Map: Tour Itinerary: Landing to PERSIA Welcome to Iran. To be met by your tour guide at the airport (IKA airport), you will be transferred to your hotel. We will visit Golestan Palace* (one of Iran UNESCO World Heritage site) and grand old bazaar of Tehran (depends on arrival time). O/N Tehran Magic of Desert (Kashan) Leaving Tehran behind, on our way to Kashan, we visit Ouyi underground city. Then continue to Kashan to visit Tabatabayi historical house, Borujerdiha/Abbasian historical house, Fin Persian garden*, a relaxing and visually impressive Persian garden with water channels all passing through a central pavilion. -

Conservation of Badgirs and Qanats in Yazd, Central Iran

PLEA2006 - The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Geneva, Switzerland, 6-8 September 2006 Conservation of Badgirs and Qanats in Yazd, Central Iran Dr Reza Abouei1, 2 1 School of Architecture, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK 2 School of Architecture, Art University of Isfahan, Isfahan, IRAN ABSTRACT: Of all historic Iranian cities, Yazd, with thousands of historic residential buildings and a large number of traditional structures such as badgirs (wind-towers) and qanats (underground tunnels) contains the largest uninterrupted historic urban fabric in Iran. The city is also an important example of Iranian urban history, whose urban fabric, well adapted to regions dry and hot climate, is relatively a living and dynamic area. The special climate of Yazd has made it necessary to adapt a particular architectural style and urban development/redevelopment schemes. Furthermore, most historic areas of the city contain various traditional structures such as the badgirs, ab-anbars (water storages) and qanats. The existence of these mud-brick ventilation structures, which dominate the city’s roofscapes, creates a distinctive architectural feature of Yazd in which an efficient clean energy system has been used for centuries. As an ancient Iranian system of irrigation, the qanats are also among the outstanding infrastructural features of Yazd in which an organised network of deep water wells linked a labyrinth of subterranean tunnels to form an artificial spring. Currently, many of these traditional structures remain in use, but the historic urban fabric of the city is under the risk of gradual depopulation. Accelerated modern technology and the change of social and economic aims of the community, in Yazd like many other historic cities, alongside the infeasibility of changes in traditional infrastructure have caused the gradual abandonment of these areas. -

Iran Painting Tour

Iran Painting Tour Available from: January 1, 2021 To December 31, 2021 Tour Destinations: Tehran to Kashan Duration: 14Days Tour styles: Style painting Nature Artistic Cultural Historical Code: PIGP Tour route: Tehran Shiraz Yazd Isfahan Maranjab Desert Kashan Tailor made Tour highlights Travel through the art history of Iran from ancient times until modern era at museums of Tehran including Iran National Museum, Islamic Art Museum, and Contemporary Art Museum of Iran Learn different techniques of Iranian painting like the Gol o Morgh technique in Shiraz and Miniature painting in Isfahan, Enjoy painting the earthen alleys of Yazd historical city, the scenic landscapes of Maranjab Desert, and the glorious ruins of Persepolis, What you need to know about this tour Iranian art or Persian art including its philosophy, history and the remained masterpieces is one of the richest in world’s art history and the masterpieces in different media like painting, architecture, calligraphy and etc. are among the fantastic samples that cause Iran to attract more and more visitors and travelers as an amazing travel destination. Iranian painting includes diverse techniques invented in different cities during historical eras as main art movements, each opening a new window to the Persian art and aesthetic world. Iran Painting Tour is one of our unique Iran tours which is designed especially for painters and art lovers. On this tour, you’ll meet successful Iranian painters of different techniques in top cities of Iran, explore the best samples of Iranian architecture, paintings and handicrafts, and spend some hours on painting and sketching the beauties and charm of Iran. -

Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes II John Shannahan BAncHist (Hons) (Macquarie University) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University. May, 2015. ii Contents List of Illustrations v Abstract ix Declaration xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Conventions xv Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY REIGN OF ARTAXERXES II The Birth of Artaxerxes to Cyrus’ Challenge 15 The Revolt of Cyrus 41 Observations on the Egyptians at Cunaxa 53 Royal Tactics at Cunaxa 61 The Repercussions of the Revolt 78 CHAPTER 2 399-390: COMBATING THE GREEKS Responses to Thibron, Dercylidas, and Agesilaus 87 The Role of Athens and the Persian Fleet 116 Evagoras the Opportunist and Carian Commanders 135 Artaxerxes’ First Invasion of Egypt: 392/1-390/89? 144 CHAPTER 3 389-380: THE KING’S PEACE AND CYPRUS The King’s Peace (387/6): Purpose and Influence 161 The Chronology of the 380s 172 CHAPTER 4 NUMISMATIC EXPRESSIONS OF SOLIDARITY Coinage in the Reign of Artaxerxes 197 The Baal/Figure in the Winged Disc Staters of Tiribazus 202 Catalogue 203 Date 212 Interpretation 214 Significance 223 Numismatic Iconography and Egyptian Independence 225 Four Comments on Achaemenid Motifs in 227 Philistian Coins iii The Figure in the Winged Disc in Samaria 232 The Pertinence of the Political Situation 241 CHAPTER 5 379-370: EGYPT Planning for the Second Invasion of Egypt 245 Pharnabazus’ Invasion of Egypt and Aftermath 259 CHAPTER 6 THE END OF THE REIGN Destabilisation in the West 267 The Nature of the Evidence 267 Summary of Current Analyses 268 Reconciliation 269 Court Intrigue and the End of Artaxerxes’ Reign 295 Conclusion: Artaxerxes the Diplomat 301 Bibliography 309 Dies 333 Issus 333 Mallus 335 Soli 337 Tarsus 338 Unknown 339 Figures 341 iv List of Illustrations MAP Map 1 Map of the Persian Empire xviii-xix Brosius, The Persians, 54-55 DIES Issus O1 Künker 174 (2010) 403 333 O2 Lanz 125 (2005) 426 333 O3 CNG 200 (2008) 63 333 O4 Künker 143 (2008) 233 333 R1 Babelon, Traité 2, pl. -

The Outbreak of the Rebellion of Cyrus the Younger Jeffrey Rop

The Outbreak of the Rebellion of Cyrus the Younger Jeffrey Rop N THE ANABASIS, Xenophon asserts that the Persian prince Cyrus the Younger was falsely accused of plotting a coup I d’état against King Artaxerxes II shortly after his accession to the throne in 404 BCE. Spared from execution by the Queen Mother Parysatis, Cyrus returned to Lydia determined to seize the throne for himself. He secretly prepared his rebellion by securing access to thousands of Greek hoplites, winning over Persian officials and most of the Greek cities of Ionia, and continuing to send tribute and assurances of his loyalty to the unsuspecting King (1.1).1 In Xenophon’s timeline, the rebellion was not official until sometime between the muster of his army at Sardis in spring 401, which spurred his rival Tissaphernes to warn Artaxerxes (1.2.4–5), and his arrival several months later at Thapsacus on the Euphrates, where Cyrus first openly an- nounced his true intentions (1.4.11). Questioning the “strange blindness” of Artaxerxes in light of Cyrus’ seemingly obvious preparations for revolt, Pierre Briant proposed an alternative timeline placing the outbreak of the rebellion almost immediately after Cyrus’ return to Sardis in late 404 or early 403.2 In his reconstruction, the King allowed Cyrus 1 See also Ctesias FGrHist 688 F 16.59, Diod. 14.19, Plut. Artax. 3–4. 2 Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander (Winona Lake 2002) 617–620. J. K. Anderson, Xenophon (New York 1974) 80, expresses a similar skepticism. Briant concludes his discussion by stating that the rebellion officially (Briant does not define “official,” but I take it to mean when either the King or Cyrus declared it publicly) began in 401 with the muster of Cyrus’ army at Sardis, but it is nonetheless appropriate to characterize Briant’s position as dating the official outbreak of the revolt to 404/3. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Sassanid Archaeological Landscape of Fars Region”

Islamic Republic of Iran Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization ICHHTO “Sassanid Archaeological Landscape of Fars Region” for inscription on the World Heritage List (Additional Information) UNESCO World Heritage Convention 2017 1 In the name of God 2 Evaluation of the nomination of the “Sassanid Archaeological Landscape of Fars Region” (Islamic Republic of Iran) for inscription on the World Heritage List This report is submitted in response to the ICOMOS letter of GB/AS/1568-AddInf-1, dated 28September 2017 on the additional information for the nomination of Sassanid Archaeological Landscape of Fars Region. The Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization is grateful to ICOMOS for its devotion to conservation and preservation of historic monuments and sites. The objective of this detailed report is to clarify the issues raised by ICOMOS in the aforementioned letter. Additional information for clarification on: - Serial approach - Risks and Factors affecting the property - Protection - Management - Monitoring 1- Serial approach Could the State Party kindly provide information on the rationale, methodology and criteria (here not referring to the nomination criteria), which guided the selection of the component sites presented in this nomination? Could the State Party kindly outline the contribution of each site component, to the overall Outstanding Universal Value in the substantial, scientific and discernible way, as outlined in paragraph 137b of the Operational Guidelines? For clarifying, the question will be explained in the parts of (1-a) and (1-b) in details: 1-a: Rationale, methodology and criteria which guided the selection of the component sites presented in this nomination: The rationale which guided the selection of the component sites is based on a methodology which takes into account their historical characteristics and at the same time considers their association with the regional landscape. -

Kashan Kashan Is a City in the Isfahan Province of Iran. Kashan Is the First

Kashan Kashan is a city in the Isfahan province of Iran. Kashan is the first of the large oases along the Qom-Kerman road which runs along the edge of the central deserts of Iran. Its charm is thus mainly due to the contrast between the parched immensities of the deserts and the greenery of the well-tended oasis. Archeological discoveries in the Sialk Hillocks which lie 2.5 miles (4 km) west of Kashan reveal that this region was one of the primary centers of civilization in pre-historic ages. Hence Kashan dates back to the Elamite period of Iran.The Sialk ziggurat still stands today in the suburbs of Kashan after 7000 years. After world known Iranian historical cities such as Isfahan and Shiraz, Kashan is a common destination for foreign tourists due to numerous historical places.Kashan Province is renowned over the centuries for its ceramic tiles, potter) textiles, carpets and silk, Kashan is an attractive oasis town and also the birthplace of the famous poet Sohrab and the artist Sepehria. Kashan is also of interest for its connections with Shah Abbas it was favorite town of his, and he beautified it and asked to be buried here. There are a surprising number of things to see in and around Kashan, so it's an ideal place to stop for a day or two . Tabatabei House The Borujerdi House is a historic house in Kashan, Iran. The house was built in 1857 by architect Ustad Ali Maryam, for the wife of Seyyed Mehdi Borujerdi, a wealthy merchant. -

Persian Heritage: a Significant Role in Achieving Sustainable Development

International Journal of Cultural Heritage E. Abedi, D. Kralj http://iaras.org/iaras/journals/ijch Persian heritage: A Significant Role in Achieving Sustainable Development ELAHEH ABEDI1, DAVORIN KRALJ2, A.M.Co., Tehran, IRAN1 ALMA MATER EUROPAEA, Slovenska 17, 2000 Maribor, SLOVENIA2, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: In every country, heritage plays a significant role in achieving sustainable development. Iran, a high plateau located at latitudes in the range of 25-40 in an arid zone in the northern hemisphere of the East, is a vast country with different climatic zones. In the past, traditional builders have presented several logical climatic solutions in order to enhance human comfort. In fact, this emphasis has been one of the most important and fundamental features of Iranian architecture. To a significant extent, Iranian architecture has been based on climate, geography, available materials, and cultural beliefs. Therefore, traditional Iranian builders had to devise various techniques to enhance architectural sustainability through the use of natural materials, and they had to do so in the absence of modern technologies. Paper describes the principals and methods of vernacular architectural designs in Iran with given examples which is predominately focused on some eclectic ancient cities in Iran as Kashan, Isfahan, and Yazd. Design and technological considerations of past, such as sustainable performance of natural materials, optimum usage of available materials, and the use of wind and solar power, were studied in order to provide effective eco architectural designs to provide the architectural criteria and insights. This study will be beneficial to today architects in the design of architectural structures to provide human comfort and a sustainable life in adverse climatic conditions. -

1 Tehran Arrivals at Tehran, Meet and Assist at Airport and Then Transfer To

Day: 1 Tehran Arrivals at Tehran, meet and assist at airport and then transfer to Hotel, after check in, visit Sa'dabad Palace, Tajrish Bazaar, Lunch at local restaurant around north of Tehran, visit Niavaran Palace. O/N: Tehran. The Sa'dabad Complex is a complex built by the Qajar and Pahlavi monarchs, located in Shemiran, Greater Tehran, Iran. Today, the official residence of the President of Iran is located adjacent to the complex. The complex was first built and inhabited by Qajar monarchs in the 19th century. After an expansion of the compounds, Reza Shah of the Pahlavi Dynasty lived there in the 1920 s, and his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, moved there in the 1970 s. After the 1979 Revolution, the complex became a museum. Tajrish Market: The market on the one hand and Rehabilitation field, from the other competent shrine and the surrounding streets have access. Reliance Big Rehabilitation is one of the oldest accents located in Tehran in this market. Rehabilitation market a small sample of the Tehran bazaar is one of the oldest shopping centers Shamiran is the bridgehead and Rehabilitation connecting the two neighborhoods. The Niavaran Complex is a historical complex situated in Shemiran, Tehran (Greater Tehran), Iran.It consists of several buildings and monuments built in the Qajar and Pahlavi eras. The complex traces its origin to a garden in Niavaran region, which was used as a summer residence by Fath-Ali Shah of the Qajar Dynasty. A pavilion was built in the garden by the order of Naser ed Din Shah of the same dynasty, which was originally referred to as Niavaran House, and was later renamed Saheb Qaranie House. -

Composition and Continuity in Sasanian Rock Reliefs

0320-07_Iran_Antiq_43_12_Thompson 09-01-2008 15:04 Pagina 299 Iranica Antiqua, vol. XLIII, 2008 doi: 10.2143/IA.43.0.2024052 COMPOSITION AND CONTINUITY IN SASANIAN ROCK RELIEFS BY Emma THOMPSON (University of Sydney, Australia) Abstract: The cliffs of Iran are adorned with rock reliefs from every period of its long history. During the years that the Sasanian dynasty ruled Iran, artists added to this collection considerably. These monuments are individual capsules of infor- mation on the general political, religious, historical and artistic milieu of the time. This paper presents a method for furthering our understanding of the Sasanian period through an analysis of the composition of each Sasanian relief. The analy- sis is based on the hypothesis that composition will serve as an indicator of artis- tic continuity and change and encode an artistic signature of sorts indicating the artists’ background and training. The initial results suggest that the reliefs of the early Sasanian period reflect the work of artists from at least two schools of art. Keywords: Sasanian, rock reliefs, composition. The kings of the Sasanian dynasty ruled Iran for over four hundred years. During the first eighty-five years of the dynasty (AD 224-309) there were seven changes of crown, many military gains and losses and thirty rock carvings were commissioned to commemorate these events. Most of these were carved in Fars, the homeland of the dynasty: eight were carved in the company of the Achaemenid tombs at Naqsh-i Rustam; six line the way to Shapur’s city at Bishapur; four were carved in the open air grotto at Naqsh- i Radjab; two were carved near Ardashir’s first city at Firuzabad and the rest were carved as single reliefs at various locations across the province of Fars: Barm-i Dilak, Sar Mashhad, Sarab-i Bahram, Guyum, Rayy, Darab- gird, and Tang-i Qandil.