Heavy Radicals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

PDF Van Tekst

Memoires 1977-1978 Willem Oltmans bron Willem Oltmans, Memoires 1977-1978. Papieren Tijger, Breda 2008 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/oltm003memo23_01/colofon.php © 2013 dbnl / Willem Oltmans Stichting 7 Inleiding 2007 was het verschrikkelijkste jaar van mijn leven. Ik kwam langzaam uit een periode van rouw, en probeerde niet alleen de dood van mijn beste vriend (september 2004) te begrijpen, maar ook te accepteren. Ik kwam terecht in 'n total burn-out. Misschien is de dood van je ouders onvermijdelijk, maar de dood van je vriend brengt een gevoel van groot verlies en alles omvattende pijn met zich mee. Ik trok me terug en sloot me op alsof de wereld niet bestond. Toen kreeg een weinig bekende virus vat op mij, en werd ik door het Guillain Barre Syndroom geveld. Van de ene dag op de andere was ik lichamelijk volkomen verlamd. Hoewel ik niet kon spreken, slikken of ademen, was mijn geest alerter en verfijnder afgestemd dan ooit. Gekoppeld aan slangen en apparatuur om mij in leven te houden, lag ik maanden op mijn rug in de intensive care. De gedachten aan diegene die ik lief had en mij steunden, gaf mij de kracht te willen herstellen. Ik moest beter worden, al was het alleen maar om diegenen, die mijn leven hadden verrijkt, te bedanken. Ik dacht aan Willem natuurlijk. WILLEM OLTMANS voor het publiek. Voor mij, simpelweg, mijn Willem. Tijdens de laatste zes maanden van zijn leven had de ziekte hem totaal uitgeput. Als gevolg daarvan werd een van zijn grootste passies van hem afgenomen. -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies. -

A Critical Guide to Intellectual Property

A CRITICAL GUIDE TO INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY A CRITICAL GUIDE TO INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY Edited by Mat Callahan and Jim Rogers A Critical Guide to Intellectual Property was first published in 2017 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Editorial Copyright © Mat Callahan and Jim Rogers 2017 Copyright in this Collection © Zed Books 2017 The rights of Mat Callahan and Jim Rogers to be identified as the editors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 Typeset in Plantin and Kievit by Swales & Willis Ltd, Exeter, Devon Index by [email protected] Cover design by Andrew Brash All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78699-114-0 (hb) ISBN 978-1-78699-113-3 (pb) ISBN 978-1-78699-115-7 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-78699-116-4 (epub) ISBN 978-1-78699-117-1 (mobi) CONTENTS Acknowledgments | vii List of abbreviations | viii 1 Why intellectual property? Why now? . 1 Mat Callahan and Jim Rogers 2 Running through the jungle: my introduction to intellectual property . 14 Mat Callahan SECTION ONE: HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS . 31 3 Intellectual property rights and their diffusion around the world: towards a global history . 33 Colin Darch 4 The political economy of intellectual property . -

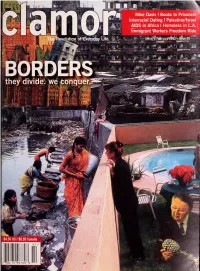

Clamor Magazine Using Our Online Clamor Is Also Available Through These Fine Distribution Outlets: AK Press, Armadillo, Desert Survey At

, r J^ I^HJ w^ litM: ia^ri^fTl^ pfn^J r@ IDS in Africa I Homeless in L.A. 1 J oniigrant Workers Freedom Ride " evolution of ^EVerycfay Life .'^ »v -^3., JanuaiV7F«bruary^0V* l^e 30 5 " -»-^ - —t«.iti '•ill1.1, #1 *ymm f**— 'J:'<Uia-. ^ they divide, we conquerJ fml^ir $4.50 us/ $6.95 Canada 7 "'252 74 "96769' fKa%'t* NEW ALBUMS JANUARY 25 'M WIDE AWAKEjrS MORNING DIGITAL ASH IN A DIGITAL URN K. OUT NOW LUA CD SINGLE from I'M WIDE AWAKE, IT'S MORNING TAKE IT EASY (LOVE NOTHING) CD SINGLE from DIGITAL ASH IN A DIGITAL URN SGN.AMBULANCE THE FAINT THE GOOD LIFE BEEP BEEP L KEY WET FROM BIRTH ALBUM OF THE YEAR BUSINESS CASUAL WWW.SADDLE-CREEK.COM | [email protected] the revolution of everyday life, delivered to your door subscribe now. $18 for one year at www.clamormagazine.org or at PO Box 20128 1 Toledo, Ohio 43610 : EDITORyPUBLISHERS Jen Angel & Jason Kucsma from your editors CONSULTING EDITOR Jason Kucsma Joshua Breitbart WEB DESIGN In November after the election, I had the fortune to sit next to an Israeli man named Gadi on CULTURE EDITOR Derek Hogue a flight from Cleveland to Detroit. He was on his way to Europe and then home, and I was on Eric Zassenhaus VOLUNTEERS my way to my sister's house in Wisconsin. ECONOMICS EDITOR Mike McHone, Our conversation, which touched on everything from Bush and Kerry to Iraq to the se- Arthur Stamoulis JakeWhiteman curity wall being built by Israel, gave me the opportunity to reflect on world politics from an MEDIA EDITOR PROOFREADERS outsider's perspective. -

Komotion Sound Mag. 1-10

InternationalKOMOTION Suddenly Ten! 2 Defining Moments 3 written by Mat Callahan “The complaint department is closed!" A phrase often Komotion: Beer, used during Komotion's formative stages. A rejoinder to One Years anyone who, in effect, was saying — "I don't like this, Ten 12 why doesn't someone do something about it?" Our point written by Claude of departure was, "We don't like this, therefore we have It Makes a Difference 15 to do something about it." Sniveling and groveling are written by Liz complementary strands in the fabric of servifude. Be- Mary Thompson moaning one's woes invests authority in those respon- Komotion Kweezeen 16 sible for creating them, reinforcing belief in the ancient written by Joe Gore credo of the oppressor; "thus it is and thus it has always been..." To act, and to call on others to act, embodies the There Comes A Time In conviction that something else, something better is Every Collective's Life possible. It is to take responsibility upon oneself and When ... 17 one's fellows for the transformation of situations and written by JosefBrinkman relationships. It is to delegitimate the authority of insti- tutions and their representatives. It is to imagine beyond Komotion Gallery 21 the limits set by "official" public discourse. Such was our written by Richard Olsen attitude, felt more than stated, when we began. Make a Komotion: Early on a sign hung prominently in our hallway declar- or, How I Learned to Mop ing: "If you wanf more information, ask. If you want to for the Revolution 23 support us, contribute. -

Chamberlain and Hitler 37

0465012756_FM.qxd:reynolds 2/6/09 1:47 PM Page a PRAISE FOR DAVID REYNOLDS’S SUMMITS “Most historians agree that summits played a central role in 20th- century international relations, but explaining how or why these meetings mattered so much has often proved frustrating. David Reynolds—a Cambridge historian—has now filled the gap with a book that is as penetrating in its overarching analysis as it is rich in detail about individual encounters at the summit: the result is a study in international history at its very finest.” —Irish Times “Behind the narrative lies a muscular analytic mind.” —Sunday Times “Lucid, authoritative account of big-power diplomatic parleys from Munich to Camp David.” —Kirkus “Reynolds had the intriguing idea of examining the conflicts of the 20th century through the lens of its pivotal summit meetings. Given his Cambridge professorship and eight books on WWII and the Cold War (Command of History), the author’s thorough mastery of his subject is reflected in the fluency and assurance of the writing.” —Publishers Weekly “Author David Reynolds takes us on a virtual trek to the summit and back in a book that is as entertaining and eye-opening as it is instructive.” —Arkansas Democrat-Gazette 0465012756_FM.qxd:reynolds 2/6/09 1:47 PM Page b “This is an essential book for a deeper understanding and apprecia- tion of the difficulties and the possibilities of international summitry.” —Lincoln Journal Star “A fascinating look at historical events through this particular lens. ” —Library Journal “Masterly . required reading.” —Spectator “David Reynolds writes with pace and verve . -

Clamor Magazine That IS Accessible to People from a Variety of Backgrounds

vashing i ion on TV I Re-Organized Labor 9 • BiliiiB 1 r iM; May/June 2005 • Issue 32 I uia: L ,»- «' i •• • iTcHU^^^ *-- i $4.50 us/ $6.95 Canada &t^??^'^:>rx 06 > Radical publisliers AK Press celebrate M»>* '252 74 "96769" r their 15th anniversary this year. ' ' ^n' I mr^^^w BRIGHT EYES petforming songs from DIGini UH IN A DIGini URN t THE miNT VISIT SADDLE-CREEK.COM FOR TOUR DATES eoMwi; soo/v - MAm TAKoe- tt:fr-epoc(rMAf24 • books, zines, CDs, DVDs, posters, gear, and much more • secure online ordering • fast shipping • new titles weekly • independent as fuck ! M I just a few of the items available at: CldlTIOr www.clamormagazJne.org/infGSHOP : EOlTORyPUBLISHERS Jen Angel & Jason Kucsma from your editors CULTURE EDITOR WEB DESIGN Eric Zassenhaus Derek Hogue Fuck tradition. It's the sort of thing that jails us and keeps us from moving forward — it ties ECONOMICS EDITOR INTERNS our hands with convention. It keeps from earning they deserve. It Arthur Stamoulis Melissa Cubria women what keeps people Dan Gordon of color shut out from resources they need to survive. Mainstream convention tells us that MEDIA EDITOR we need to adhere to tradition to maintain our roots, but what traditions are we encouraged Catherine Komp VOLUNTEERS Mike McHone to adhere toi* Traditions that keep certain people in power while others are left to fend for PEOPLE EDITOR Sheryl Siegenthaier themselvesJ* What about the traditions of resistance that encourage us to continue fighting Keidra Chaney PROOFREADERS for a better world for all of us? Noam Chomsky once suggested that "intellectual tradition is SEX &GENDER EDITOR Mike McHone. -

The Cold War and the Change in the Nature of Military Power

The Cold War and the Change in the Nature of Military Power by: Lee M. Peterson supervisor: Dr. Christopher Coker UMI Number: U615441 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615441 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I SO 53 Abstract The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989 was called by many observers of international affairs the end of the Cold War. However, fifteen years earlier, commentators such as Alistair Buchan had also declared the end of the Cold War. Was this just an premature error on Buchan's part or is there a link between the events of the early 1970s, which is referred to as the era of detente and those leading up to the collapse of the Berlin Wall? It is the intention of this thesis to argue that these periods are integrally related mainly by the fact that they were each periods when one of the two superpowers was forced to re evaluate their foreign policies. The re-evaluations were brought about by changes in the international arena, most importantly a change in the nature of military power. -

British Policy and the Occupation of Austria, 1945-1955

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses British Policy and the Occupation of Austria, 1945-1955. Williams, Warren Wellde How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Williams, Warren Wellde (2004) British Policy and the Occupation of Austria, 1945-1955.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa43184 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ British Policy and the Occupation of Austria,1945 -1 9 5 5 Warren Wellde Williams Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2004 ProQuest Number: 10821576 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Cold War by “Other Means”: Canada’S Foreign Relations with Communist Eastern Europe, 1957-1963

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2017 Cold War by “Other Means”: Canada’s Foreign Relations with Communist Eastern Europe, 1957-1963 Cory Scurr [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Scurr, Cory, "Cold War by “Other Means”: Canada’s Foreign Relations with Communist Eastern Europe, 1957-1963" (2017). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1989. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1989 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cold War by “Other Means”: Canada’s Foreign Relations with Communist Eastern Europe, 1957-1963 by D. Cory Scurr DISSERTATION Submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Wilfrid Laurier University Waterloo, Ontario, Canada © D. Cory Scurr 2017 1 Table of Contents Abstract: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements: …………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………... 4 Chapter 1: Changes Behind the Curtain: the Soviet Economic Offensive & Canadian-Soviet Diplomatic Relations ……………………………………… -

Britain and the Soviet Union: the Search for an Interim Agreement on West Berlin November 1958-May 1960

Britain and the Soviet Union: The Search for an Interim Agreement on West Berlin November 1958-May 1960 A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Kathleen Paula Newman London School of Economics and Political Science October 1999 l UMI Number: U615582 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615582 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7 7 5 8 733 363 Abstract Britain and the Soviet Union: The Search for an Interim Agreement on West Berlin November 1958-May 1960 This thesis analyses British and Soviet policy towards negotiations on an Interim Agreement on Berlin, from November 1958 until May 1960. It emphasises the crucial role played by the British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan and the Soviet Premier, Nikita Khrushchev, both of whom viewed the Berlin problem within the wider context of their mutual objectives of achieving detente and disarmament. The opening chapter analyses Soviet motivation for reactivating the Berlin question, and emphasises two factors behind Soviet policy: the maintenance of the status quo in Germany and Eastern Europe, and Soviet fears of the nuclearisation of the Bundeswehr.