TTWALL Book FINAL 4-10-05

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies. -

2014 Banquet & Event Menus

2014 BANQUET & EVENT MENUS the homestead THE OMNI HOMESTEAD RESORT 2014 BANQUET & EVENT MENUS The Omni Homestead Resort is one of America’s grand resorts, offering unparalled hospitality and southern charm in a 2,000-acre setting in the Allegheny Mountains of Virginia. Renowned for its natural hot springs, the resort features an expansive Spa, two championship golf courses, a two-acre family-friendly water park, tennis, falconry, Segway tours, Shooting Club, fly fishing, archery, miniature golf, horseback riding, skiing, snowboarding, and ice skating. 7696 Sam Snead Highway Hot Springs, VA 24445 (800) 838-1766 thehomestead.com the homestead Boxed Breakfast $15 Plated Breakfast BREAKFAST All plated breakfasts are served with: Select Homestead Bakery Pastries including the Famous Homestead Doughnuts, Apple Preserves and Homestead Creamery Butter, Fresh Orange Juice, Arabica Coffees and Gourmet Teas. Chilled Seasonal Fruit Starters Atlantic Smoked Salmon on New York Style Bagel Seasonal Fruit and Wild Berries over Toasted Coconut Chive and Caper Cream Cheese with Mascarpone Pickled Red Onion Or Peach and Brambleberry Parfait with House Granola and Or Hungry Hill Honey Yogurt Virginia Ham and Cheddar Biscuit Entrées Herbed Homestead Creamery Butter Malted Waffle $18 Seasonal Breakfast Breads with Cinnamon and Toasted and Power Bar Walnut Butter, Warm Maple Syrup Cheddar Scrambled Eggs $20 Edwards Smoked Bacon and Pan Seared Country Sausage, Home Fried Potatoes with Caramelized Onion Steak and Eggs $27 Petite Grilled Flat Iron Steak and Country Scrambled Eggs, Griddled Hash Brown Potatoes, Oven Dried Tomato, Butler Passed Sauce Bernaise 23% Taxable Service Charge and 9.3% Sales Tax will be added to all Charges. -

Dessert Menu Dessert Cocktails

DESSERT MENU DESSERT COCKTAILS ESPRESSO MARTINI 20 Patron XO café tequila, Vanilla vodka and a shot of Cuban coffee TOBLERONE (CUBAN STYLE) 22 DESSERTS Spiced rum, Baileys, Kahlua, Frangelico and hazelnut syrup served over vanilla ice cream and crumbled biscuit SPANISH CHURROS 15 RUM BLAZER 22 Served with dark chocolate dipping sauce Ron Zacapa 23, orange curaco, house made spiced syrup and and Bailey’s infused cream Mr Wray and Nephew to light this cocktail up! Served warm MOJITO CHEESECAKE 16 THE DESSERT 30 Lime, mint and rum cheesecake Almond Panacota served in a martini glass with white and with ginger biscuit base dark chocolate crumble, crushed raspberries, amareno cherries matched beautifully with cachaca, Brazilian rum ARGENTINIAN CREPE 15 With banana and chocolate sauce served alongside vanilla bean ice cream TRADITIONAL LIQUOR COFFEE CUBAN COFFEE Served with homemade biscuit 15 HOT CHOCOLATE PUDDING We use authentic Cuban coffee Please allow at least 20 minutes CLASSIC HAVANA 22 beans – superb single origin, Havana Especial, Grand With vanilla bean ice cream and rich, full bodied and smooth a white chocolate biscuit crumb Marnier, Dark Chocolate with a hint of spice. For a true Liquor and orange marmalade Cuban coffee experience we 18 with vanilla ice cream CARAMEL AND PEAR TATIN recommend: With burnt caramel ice cream IRISH COFFEE 20 CAFECITO 4 and butterscotch sauce Jameson Irish Whisky Espresso sweetened with and whipped cream ALMOND PANA COTA 15 demerera sugar With a blueberry compote CORTADITO 4 CARIBBEAN COFFEE 22 Small cut of milk over a Premium coconut rum, sweetened Cuban espresso thickened cream, coffee and Bailey’s cream CAFÉ CON LECHE 5 Coffee, milk and sugar served separately on your own board AFTER DINNER RUMS Cuba is often called the “isle of rum” and here at The Cuban we COFFEE E X T R A S house some of the world’s finest rums. -

New Owners Hope to Sweeten up Sweet Shop BATTLE BLUEBERRY

StarNews | StarNewsOnline.com | Wednesday, June 17, 2015 C1 UNEXPECTED DELIGHT Head to Beauchaine’s 211 in Surf City Food & Drink for seafood that goes beyond the usual beachside fare. Check out LIFE Jason Frye’s review. C2 BITES & SIPS New owners hope to sweeten up sweet shop BATTLE BLUEBERRY PAUL STEPHEN COBBLER ast week Wes and Kristen Bechtel L became just about the coolest parents a pair of daughters could ask for. VS. PIE Leaving his post with Verizon and hers as a Which treatment is best for this season’s abundance of berries? paralegal, the two have gone full-time into the Paul Stephen world of frozen confec- [email protected] tions as the new owners of Wilmington insti- t’s time for a blueberry battle royale. It’s no secret the Blueberries are kind of a big deal around here. tution Boombalatti’s The sleepy town of Burgaw transforms into ground zero for the N.C. Blueberry Festival this week- Homemade Ice Cream . end, offering plenty of muffins, cakes, breads, ice creams and other confections. But for many of us, it And the Bechtels’ girls, I really only boils down to one contest: cobbler vs. pie. Airlie, 6, and Stella, 3, are already having an Sure, they’re both deli- countless other skirmishes, Online Poll If you go impact on the menu; cious, and nobody in their it’s rare to find someone Wes unveiled a water- right mind would ever turn who doesn’t feel pas- ■ W e’d love to What: N.C. Blueberry Festival melon sorbet last week down either. -

Heavy Radicals

WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING ABOUT HEAVY RADICALS Heavy Radicals is a concise and insightful history of a long- forgotten but vibrant radical movement. Leonard and Gallagher break new ground in revealing the extent to which law enforcement will go to infiltrate, destabilize and ultimately destroy domestic political organizations that espouse a philosophy counter to the status quo. To better understand the current state of domestic surveillance and political repression, from Occupy Wall Street to the Edward Snowden revelations, start with this little gem of a book. T.J. English, author of The Savage City and Havana Nocturne In this masterfully written and extensively researched book, Aaron Leonard with Conor A. Gallagher offers a no-nonsense critical analysis of one of the most resilient, misunderstood, and controversial anti-capitalist organizations of the last fifty years. This book is a MUST READ for anyone invested in nuancing their understanding of revolutionary political struggle and unrelenting state repression in the United States. Robeson Taj Frazier, author of The East Is Black: Cold War China in the Black Radical Imagination Based on impeccable research, Heavy Radicals explores the rise of the Revolutionary Communist Party in the late 1960s and 1970s. Militant Maoists, dedicated to revolutionary class struggle, the RCP was one of many organizations that fought to carry on the 60s struggle for radical change in the United States well after SDS and other more well known groups imploded. Leonard and Gallagher help us to understand how the RCP’s revolutionary ideology resonated with a small group of young Heavy Radicals: The FBI’s Secret War on America’s Maoists people in post-1968 America, took inspiration from the People’s Republic of China, and brought down the wrath of the FBI. -

Stories of Cuban-Americans Living and Learning Bilingually

STORIES OF CUBAN-AMERICANS LIVING AND LEARNING BILINGUALLY By Natasha Perez A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Curriculum, Instruction, and Teacher Education – Doctor of Philosophy 2017 ABSTRACT STORIES OF CUBAN-AMERICANS LIVING AND LEARNING BILINGUALLY By Natasha Perez This study explores the interplay of bilingualism, identity, literacy and culture for Cuban- American students in the Cuban diaspora. I contextualize their experiences within the social, historical, and political background of Cuban immigration, situating their stories within the conflicting narratives of Cuban-American imagination in the U.S., to explore how manifestations of Cubania shape the language and literacy practices of Cuban-American youth across generations and contexts, within three U.S. states. Inspired by traditions of phenomenology and narrative inquiry (Clandelin & Connoly, 2000), this study is an intentional narrative “reconstruction of a person’s experience in relationship both to the other and to a social milieu” (CC 200-5), drawing from three narratives of experience, including my own. The three narratives are based on the experiences Cuban- American adolescent girls growing up in different contexts, in search of answers to the following questions: a) For each participant in this study, what are the manifestations of Cuban identity, or Cubania? b) What are the factors that sustain different or similar manifestations of Cubania, both within and across generations of immigrants? c) How, if at all, do manifestations of Cubania shape the language and literacy practices of Cuban-American youth? The narratives in this study demonstrate how language, collective memory, and context become semiotic resources that come to bear on the diasporic identities of the participants. -

Wish List 03.03.03 Vertical Epic Ale (Stone Brewing Co) 05.05.05

Wish List 03.03.03 Vertical Epic Ale (Stone Brewing Co) 05.05.05 Vertical Epic Ale (Stone Brewing Co) 07.07.07 Vertical Epic Ale (Stone Brewing Co) 09.09.09 Vertical Epic Ale (Stone Brewing Co) 10 (Two Brothers Brewing Company) 10 Commandments (The Lost Abbey) 100% Farro (La Petrognola) 10th Anniversary Double India Pale Ale (Middle Ages Brewing Co) 10th Anniversary Old Ale (Southampton Publick House) 110K+OT [Batch 1 - Der Rauch Gott](Cigar City) 110K+OT [Batch 1 - I.R.I.S] (Cigar City) 12th Anniversary Bitter Chocolate Oatmeal Stout (Stone Brewing Co) 2 Turtle Doves (The Bruery) 21st Amendment Imperial Stout (21st Amendment Brewery) 21st Amendment Live Free or Die (21st Amendment Brewery) 21st Amendment Monks Blood (21st Amendment Brewery) 21st Amendment Watermelon Wheat (21st Amendment Brewery) 30 E Lode (Birrificio Le Baladin) 30th Anniversary Flashback Ale (Boulder Beer / Wilderness Pub) 50 Degrees North-4 Degrees East (Brasserie Cantillon) 6th Anniversary Ale (Stone Brewing Co) 8th Anniversary Ale (Stone Brewing Co) 80 Shilling Scotch Ale (Portsmouth Brewery) 84/09 Double Alt (Widmer Brothers Brewing Company) Aardmonnik - Earthmonk (De Struise Brouwers) Abbot 12 (Southampton Publick House) Abstrakt #1 (Brewdog) Abstrakt #2 (Brewdog) Abstrakt #3 (Brewdog) Abyss (Deschutes Brewery) Adam (Hair of the Dog Brewing Company) Adoration Ale (Brewery Ommegang) Agave (Mountain Meadows Mead) Ahtanumous IPA (Flossmoor Station Restaurant & Brewery) Ale Mary (RCH Brewery) Almond '22 Nigra (Almond '22 Beer) Almond '22 Torbatta (Almond '22 Beer) -

A Critical Guide to Intellectual Property

A CRITICAL GUIDE TO INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY A CRITICAL GUIDE TO INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY Edited by Mat Callahan and Jim Rogers A Critical Guide to Intellectual Property was first published in 2017 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Editorial Copyright © Mat Callahan and Jim Rogers 2017 Copyright in this Collection © Zed Books 2017 The rights of Mat Callahan and Jim Rogers to be identified as the editors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 Typeset in Plantin and Kievit by Swales & Willis Ltd, Exeter, Devon Index by [email protected] Cover design by Andrew Brash All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78699-114-0 (hb) ISBN 978-1-78699-113-3 (pb) ISBN 978-1-78699-115-7 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-78699-116-4 (epub) ISBN 978-1-78699-117-1 (mobi) CONTENTS Acknowledgments | vii List of abbreviations | viii 1 Why intellectual property? Why now? . 1 Mat Callahan and Jim Rogers 2 Running through the jungle: my introduction to intellectual property . 14 Mat Callahan SECTION ONE: HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS . 31 3 Intellectual property rights and their diffusion around the world: towards a global history . 33 Colin Darch 4 The political economy of intellectual property . -

WYNWOOD BRUNCH Gr

BRUNCH BACON OMELET BACON SCRAMBLE EGGS SALMON BAGEL BACON, MIX ΤΥΡΙΩΝ, BACON, ΦΡΕΣΚΟ ΠΙΠΕΡΙ, ΨΩΜΙ BAGEL ME ΑΥΓΑ, MINI BRIOCHE CHEDDAR SAUCE, ΑΥΓΑ, ΠΑΠΑΡΟΥΝΟΣΠΟΡΟ, 6.40 ΨΩΜΙ BRIOCHE ΚΑΠΝΙΣΤΟΣ ΣΟΛΟΜΟΣ, 7.20 GUACAMOLE, SMOKY PORKY BENEDICT TURKEY OMELET CREAM CHEESE, ΚΑΠΝΙΣΤΟ ΧΟΙΡΙΝΟ, ΚΑΠΝΙΣΤΗ ΓΑΛΟΠΟΥΛΑ, BROCCOLI & SALMON ΒΑΛΕΡΙΑΝΑ BRIOCHE, HOLLANDAISE, MIX ΤΥΡΙΩΝ, ΑΥΓΑ, SCRAMBLE EGGS 8.50 EGGS ΑΥΓΑ ΠΟΣΕ MINI BRIOCHE ΜΠΡΟΚΟΛΟ, ΣΟΛΟΜΟΣ, 7.30 6.50 SOUR CREAM, ΣΧΟΙΝΟΠΡΑΣΟ, ΨΗΜΕΝΟ SPINACH BABY TURKEY BENEDICT MUSHROOM OMELET ΣΚΟΡ∆Ο, ΑΥΓΑ, ΚΑΠΝΙΣΤΗ ΓΑΛΟΠΟΥΛΑ, ΜΑΝΙΤΑΡΙΑ, ΣΚΟΡ∆Ο, ΨΩΜΙ BRIOCHE BRIOCHE, BABY ΣΠΑΝΑΚΙ, ΠΑΡΜΕΖΑΝΑ, MIX ΤΥΡΙΩΝ, 8.00 ΑΥΓΑ ΠΟΣΕ, DIJONAISSE ΛΑ∆Ι ΤΡΟΥΦΑΣ, ΣΧΟΙΝΟ- 7.50 ΠΡΑΣΟ, ΑΥΓΑ, MINI BRIOCHE BIG MOUTH TOAST 6.80 BRIOCHE TOAST, ΒΟΥΤΥΡΟ, CREAMY SALMON BENEDICT MIX ΤΥΡΙΩΝ, ΚΑΠΝΙΣΤΗ ΚΑΠΝΙΣΤΟΣ ΣΟΛΟΜΟΣ, PROVOLA CHICKEN OMELET ΓΑΛΟΠΟΥΛΑ, ΑΥΓΟ BRIOCHE, CREAM CHEESE, ΚΟΤΟΠΟΥΛΟ, BABY ΤΗΓΑΝΗΤΟ, HOLLANDAISE ΜΠΡΙΚ, ΣΧΟΙΝΟΠΡΑΣΟ, ΣΠΑΝΑΚΙ, ΜΑΝΙΤΑΡΙΑ, ΑΥΓΑ, SAUCE ΑΥΓΑ ΠΟΣΕ MINI BRIOCHE 6.50 9.50 8.50 ΓΙΑΟΥΡΤΙ ΜΕ GRANOLA, ΦΡΕΣΚΑ ΦΡΟΥΤΑ ΚΑΙ ΜΕΛΙ 6.00 COMBO BRUNCH 14.00 ΜΕΣΑΙΟ ΜΕΓΕΘΟΣ ΟΜΕΛΕΤΑ ΒACON & BRIOCHE 30gr VITALITY BOWLS PANCAKE ΜΠΑΝΑΝΑ-NUCREMA IMMUNITY 7.30 ΚΑΦΕΣ - ΦΡΕΣΚΟΣ ΧΥΜΟΣ ΠΟΡΤΟΚΑΛΙ - DETOX SHOT ΜΠΑΝΑΝΑ, ΓΑΛΑ ΡΥΖΙΟΥ, BLUEBERRIES, ΧΟΥΡΜA∆ΕΣ, ΣΙΡΟΠΙ ΒΑΝΙΛΙΑ, ΚΑΣΤΑΝΗ ΖΑΧΑΡΗ, GRANOLA USAIN BOWL 7.20 ΜΠΑΝΑΝΑ, ΓΑΛΑ ΡΥΖΙΟΥ, ΚΑΚΑΟ, ΧΟΥΡΜΑ∆ΕΣ, ΣΙΡΟΠΙ ΒΑΝΙΛΙΑ, ΚΑΣΤΑΝΗ ΖΑΧΑΡΗ, GRANOLA, ΦΡΑΟΥΛΑ, ΦΟΥΝΤΟΥΚΙ, ΣΠΟΡΟΙ ΚΑΝΑΒΗΣ, MACA SWEET WARRIOR BOWL 7.90 CINNAMON ROLL 6.00 ΜΠΑΝΑΝA, ΓΑΛΑ ΡΥΖΙΟΥ, ΦΥΣΤΙΚΟΒΟΥΤΥΡΟ, 4x PANCAKE, ΣΙΡΟΠΙ ΚΑΝΕΛΑΣ, FROSTING -

Click on the Magazine Cover

---- Welcome ---- Welcome to the 7th issue of the Best of Northwest back, and they’re also likely to shout to the roof Arkansas Top 10, the list you can’t pay to be on. tops about the awesome merits of our wonderful The magazine is growing by leaps and bounds and part of the country. currently reaches more than 250,000 each month in print, online and across all our social media This issue showcases restaurants, seasonal things outlets. We are so thankful to all our readers andto do and terrific places to stay. If you are a visitor, social media followers for your continued support. newcomer or resident you can use this magazine Fans tell us that they can’t wait for each new issueas a handy reference guide to help you pick the so they can find out about all the great places tobest places throughout Northwest Arkansas. Many eat, play and stay in NWA. readers keep a copy in their cars so they can spot at a glance where to go for a good experience. The number one question we are asked is, how are the winners chosen for your Top 10 lists? We We’ve updated all categories in this issue, and use a proprietary algorithm, which is based on we’ve also added some new ones: thousands of online reviews, select reader polls Bakeries and the undercover experiences of members of Gluten Free the NWATravelGuide.com’s street team. You Wings could liken members of the street team to mystery Consignment Clothing Stores shoppers. Based on these three different research Experience Dickson Street methods, we are able to select, with great accuracy, Sports Bars the Top 10 in any given category. -

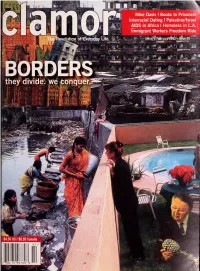

Clamor Magazine Using Our Online Clamor Is Also Available Through These Fine Distribution Outlets: AK Press, Armadillo, Desert Survey At

, r J^ I^HJ w^ litM: ia^ri^fTl^ pfn^J r@ IDS in Africa I Homeless in L.A. 1 J oniigrant Workers Freedom Ride " evolution of ^EVerycfay Life .'^ »v -^3., JanuaiV7F«bruary^0V* l^e 30 5 " -»-^ - —t«.iti '•ill1.1, #1 *ymm f**— 'J:'<Uia-. ^ they divide, we conquerJ fml^ir $4.50 us/ $6.95 Canada 7 "'252 74 "96769' fKa%'t* NEW ALBUMS JANUARY 25 'M WIDE AWAKEjrS MORNING DIGITAL ASH IN A DIGITAL URN K. OUT NOW LUA CD SINGLE from I'M WIDE AWAKE, IT'S MORNING TAKE IT EASY (LOVE NOTHING) CD SINGLE from DIGITAL ASH IN A DIGITAL URN SGN.AMBULANCE THE FAINT THE GOOD LIFE BEEP BEEP L KEY WET FROM BIRTH ALBUM OF THE YEAR BUSINESS CASUAL WWW.SADDLE-CREEK.COM | [email protected] the revolution of everyday life, delivered to your door subscribe now. $18 for one year at www.clamormagazine.org or at PO Box 20128 1 Toledo, Ohio 43610 : EDITORyPUBLISHERS Jen Angel & Jason Kucsma from your editors CONSULTING EDITOR Jason Kucsma Joshua Breitbart WEB DESIGN In November after the election, I had the fortune to sit next to an Israeli man named Gadi on CULTURE EDITOR Derek Hogue a flight from Cleveland to Detroit. He was on his way to Europe and then home, and I was on Eric Zassenhaus VOLUNTEERS my way to my sister's house in Wisconsin. ECONOMICS EDITOR Mike McHone, Our conversation, which touched on everything from Bush and Kerry to Iraq to the se- Arthur Stamoulis JakeWhiteman curity wall being built by Israel, gave me the opportunity to reflect on world politics from an MEDIA EDITOR PROOFREADERS outsider's perspective.