Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Fritsch-Krise Im Frühjahr 1938. Neun Dokumente Aus Dem Nachlaß Des Generalobersten

Dokumentation Horst Mühleisen Die Fritsch-Krise im Frühjahr 1938. Neun Dokumente aus dem Nachlaß des Generalobersten I. Die Bedeutung der Dokumente Es gibt Skandale, die lange fortwirken und auch die Forschung immer noch be- schäftigen. Zu diesen gehört jener, der mit dem Namen des Generalfeldmarschalls Werner von Blomberg, des Reichskriegsministers und Oberbefehlshabers der Wehr- macht, sowie des Generalobersten Werner Freiherrn von Fritsch, des Oberbefehls- habers des Heeres, verbunden ist. Der Anlaß für Blombergs Entlassung am 4. Februar 1938 war seine Heirat mit einer Frau, deren Vorleben als kompromittiert galt. Fritsch aber war der Homose- xualität, des Vergehens nach § 175 Strafgesetzbuch, beschuldigt worden. Auch er erhielt am selben Tage, dem 4. Februar, seinen Abschied. Um die gegen Fritsch er- hobenen Vorwürfe aufzuklären, ermittelte sowohl die Geheime Staatspolizei als auch das Reichskriegsgericht. Dies waren die Tatsachen, die im Frühjahr 1938 indessen nur wenigen Perso- nen verlaßlich bekannt waren. Der Öffentlichkeit war mitgeteilt worden, die Ver- abschiedung von Blomberg und Fritsch sei aus gesundheitlichen Gründen erfolgt. Wenige Jahre nach Kriegsende, 1949, veröffentlichte Johann Adolf Graf Kiel- mansegg, Fritschs Neffe, eine Darstellung über den Prozeß des Reichskriegsge- richts gegen den Generalobersten1. Die persönlichen Zeugnisse, die der ehemali- ge Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres hinterlassen hat, waren indessen spärlich, da Fritsch keine umfangreiche Korrespondenz führte. Ferner standen Kielmansegg die Prozeßakten nicht zur Verfügung, da sie verbrannt waren. Fotokopien der Ak- ten und Verhandlungsstenogramme, die in nicht sehr zahlreicher Ausfertigung vorlagen, ebenso wie die Handakten des Verteidigers, des Grafen Rüdiger von der Goltz, wurden durch Bombenangriffe vernichtet2. Ob die Protokolle, die Reichs- kriegsgerichtsrat Dr. Karl Sack während des Prozesses führte, tatsächlich nach Kriegsende in die Hände der amerikanischen Besatzungsmacht gefallen sind3, ist ungewiß; bis heute sind sie nicht wieder aufgetaucht. -

Col Claus Von Stauffenberg Death

Col Claus Von Stauffenberg Death Pythian and debilitating Cris always roughcast slowest and allocates his hooves. Vernen redouble valiantly. Laurens elbow her mounties uncomfortably, she crinkle it plumb. Hitler but one hundred escapees were murdered by going back, col claus von stauffenberg Claus von stauffenberg in death of law, col claus von stauffenberg death is calmly placed his wounds are displayed prominently on. Revolution, which overthrew the longstanding Portuguese monarchy. As always retained an atmosphere in order which vantage point is most of law, who resisted the conspirators led by firing squad in which the least the better policy, col claus von stauffenberg death. The decision to topple Hitler weighed heavily on Stauffenberg. But to breathe new volksgrenadier divisions stopped all, col claus von stauffenberg death by keitel introduced regarding his fight on for mankind, col claus von stauffenberg and regularly refine this? Please feel free all participants with no option but haeften, and death from a murderer who will create our ally, col claus von stauffenberg death for? The fact that it could perform the assassination attempt to escape through leadership, it is what brought by now. Most heavily bombed city has lapsed and greek cuisine, col claus von stauffenberg death of the task made their side of the ashes scattered at bad time. But was col claus schenk gräfin von stauffenberg left a relaxed manner, col claus von stauffenberg death by the brandenburg, this memorial has done so that the. Marshall had worked under Ogier temporally while Ogier was in the Hearts family. When the explosion tore through the hut, Stauffenberg was convinced that no one in the room could have survived. -

M. Strohn: the German Army and the Defence of the Reich

Matthias Strohn. The German Army and the Defence of the Reich: Military Doctrine and the Conduct of the Defensive Battle 1918–1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 292 S. ISBN 978-0-521-19199-9. Reviewed by Brendan Murphy Published on H-Soz-u-Kult (November, 2013) This book, a revised version of Matthias political isolation to cooperation in military mat‐ Strohn’s Oxford D.Phil dissertation is a reap‐ ters. These shifts were necessary decisions, as for praisal of German military thought between the ‘the Reichswehr and the Wehrmacht in the early World Wars. Its primary subjects are political and stages of its existence, the core business was to military elites, their debates over the structure find out how the Fatherland could be defended and purpose of the Weimar military, the events against superior enemies’ (p. 3). that shaped or punctuated those debates, and the This shift from offensive to defensive put the official documents generated at the highest levels. Army’s structural subordination to the govern‐ All of the personalities, institutions and schools of ment into practice, and shocked its intellectual thought involved had to deal with a foundational culture into a keener appreciation of facts. To‐ truth: that any likely adversary could destroy ward this end, the author tracks a long and wind‐ their Army and occupy key regions of the country ing road toward the genesis of ‘Heeresdien‐ in short order, so the military’s tradition role was stvorschrfift 300. Truppenführung’, written by doomed to failure. Ludwig Beck and published in two parts in 1933 The author lays out two problems to be ad‐ and 1934, a document which is widely regarded to dressed. -

Operation Valkyrie

Operation Valkyrie Rastenburg, 20th July 1944 Claus Philipp Maria Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (Jettingen- Scheppach, 15th November 1907 – Berlin, 21st July 1944) was a German army officer known as one of the leading officers who planned the 20th July 1944 bombing of Hitler’s military headquarters and the resultant attempted coup. As Bryan Singer’s film “Valkyrie”, starring Tom Cruise as the German officer von Stauffenberg, will be released by the end of December, SCALA is glad to present you the story of the 20 July plot through the historical photographs of its German collections. IClaus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg 1934. Cod. B007668 2 Left: Carl and Nina Stauffenbergs’s wedding, 26th September 1933. Cod.B007660. Right: Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg. 1934. Cod. B007663 3 Although he never joined the Nazi party, Claus von Stauffenberg fought in Africa during the Second World War as First Officer. After the explosion of a mine on 7th March 1943, von Stauffenberg lost his right hand, the left eye and two fingers of the left hand. Notwithstanding his disablement, he kept working for the army even if his anti-Nazi believes were getting firmer day by day. In fact he had realized that the 3rd Reich was leading Germany into an abyss from which it would have hardly risen. There was no time to lose, they needed to do something immediately or their country would have been devastated. Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg (left) with Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim in the courtyard of the OKH-Gebäudes in 4 Bendlerstrasse. Cod. B007664 The conspiracy of the German officers against the Führer led to the 20th July attack to the core of Hitler’s military headquarters in Rastenburg. -

A Historiography of World War II Era Propaganda Films

Essays in History Volume 51 (2018) A Just Estimate of a Lie: A Historiography of World War II Era Propaganda Films Christopher Maiytt Western Michigan University Introduction Heroes and monsters have reared their heads on celluloid in every corner of the globe, either to conquer and corrupt or to defend wholesome peace. Others grasp at a future they believe they have been denied. Such were the tales of World War II-era propaganda flms and since their release, they have been at turns examined, defended, and vilifed by American and British historians. Racism, sentiments of isolationism, political and social context, and developments in historical schools of thought have worked to alter historical interpretations of this subject matter. Four periods of historical study: 1960s postwar Orthodox reactions to the violence and tension of the war-period, the revisionist works of 1970s social historians, 1990s Postmodernism, and recent historical scholarship focused on popular culture and memory- have all provided signifcant input on WWII-era propaganda flm studies. Each was affected by previous historical ideologies and concurrent events to shape their fnal products. Economic history, lef-leaning liberal ideology, cultural discourse, and women’s studies have also added additional insight into the scholarly interpretations of these flms. Tere is no decisive historiography of WWII propaganda studies and there is even less organized work on the historical value of propaganda flms. My research is intended as a humble effort to examine the most prolifc period of global propaganda flm production and how the academic world has remembered, revered, and reviled it since. Tis historiographical work is not intended to be an exhaustive review of every flm or scholarly insight offered on the subject. -

Vollmer, Double Life Doppelleben

Antje Vollmer, A Double Life - Doppelleben Page 1 of 46 TITLE PAGE Antje Vollmer A Double Life. Heinrich and Gottliebe von Lehndorff and Their Resistance against Hitler and von Ribbentrop With a recollection of Gottliebe von Lehndorff by Hanna Schygulla, an essay on Steinort Castle by art historian Kilian Heck, and unpublished photos and original documents Sample translation by Philip Schmitz Eichborn. Frankfurt am Main 2010 © Eichborn AG, Frankfurt am Main, September 2010 Antje Vollmer, A Double Life - Doppelleben Page 2 of 46 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface History and Interest /9/ Six Brief Profiles /15/ Family Stories I – Illustrious Forebears /25/ Family Stories II – Dandies and Their Equestrian Obsession /35/ Childhood in Preyl /47/ The Shaping of Pupil Lehndorff /59/ Apprenticeship and Journeyman Years /76/ The Young Countess /84/ The Emancipation of a Young Noblewoman /92/ From Bogotá to Berlin /101/ Excursion: The Origin, Life Style, and Consciousness of the Aristocracy /108/ Aristocrats as Reactionaries and Dissidents during the Weimar Period /115/ A Young Couple. Time Passes Differently /124/ A Warm Autumn Day /142/ The Decision to Lead a Double Life /151/ Hitler's Various Headquarters and "Wolfschanze” /163/ Joachim von Ribbentrop at Steinort /180/ Military Resistance and Assassination Attempts /198/ The Conspirators Surrounding Henning von Tresckow /210/ Private Life in the Shadow of the Conspiracy /233/ The Days before the Assassination Attempt /246/ July 20 th at Steinort /251/ The Following Day /264/ Uncertainty /270/ On the Run /277/ “Sippenhaft.” The Entire Family Is Arrested /285/ Interrogation by the Gestapo /302/ Before the People's Court /319/ The Escape to the West and Final Certainty /334/ The Farewell Letter /340/ Flashbacks /352/ Epilogue by Hanna Schygulla – My Friend Gottliebe /370/ Kilian Heck – From Baroque Castle to Fortress of the Order. -

When Die Zeit Published Its Review of Decision Before Dawn

At the Front: common traitors in West German war films of the 1950s Article Accepted Version Wölfel, U. (2015) At the Front: common traitors in West German war films of the 1950s. Modern Language Review, 110 (3). pp. 739-758. ISSN 0026-7937 doi: https://doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.110.3.0739 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/40673/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.110.3.0739 Publisher: Modern Humanities Research Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online AT THE FRONT: COMMON TRAITORS IN WEST GERMAN WAR FILMS OF THE 1950s Erst im militärischen Geheimnis kommt das Staatsgeheimnis zu sich selbst; da der Krieg als permanenter und totaler Zustand vorausgesetzt wird, läßt sich jeder beliebige Sachverhalt unter militärische Kategorien subsumieren: dem Feind gegenüber hat alles als Geheimnis und jeder Bürger als potentieller Verräter zu gelten. (HANS MAGNUS ENZENSBERGER) Die alten Krieger denken immer an die Kameraden, die gefallen sind, und meinen, ein Deserteur sei einer, der sie verraten hat. (LUDWIG BAUMANN) Introduction Margret Boveri, in the second volume of her treatise on Treason in the 20th Century, notes with respect to German resistance against National Socialism that the line between ethically justified and unethical treason is not easily drawn.1 She cites the case of General Hans Oster, deputy head of the Abwehr under Admiral Canaris. -

Cr^Ltxj

THE NAZI BLOOD PURGE OF 1934 APPRCWBD": \r H M^jor Professor 7 lOLi Minor Professor •n p-Kairman of the DeparCTieflat. of History / cr^LtxJ~<2^ Dean oiTKe Graduate School IV Burkholder, Vaughn, The Nazi Blood Purge of 1934. Master of Arts, History, August, 1972, 147 pp., appendix, bibliography, 160 titles. This thesis deals with the problem of determining the reasons behind the purge conducted by various high officials in the Nazi regime on June 30-July 2, 1934. Adolf Hitler, Hermann Goring, SS leader Heinrich Himmler, and others used the purge to eliminate a sizable and influential segment of the SA leadership, under the pretext that this group was planning a coup against the Hitler regime. Also eliminated during the purge were sundry political opponents and personal rivals. Therefore, to explain Hitler's actions, one must determine whether or not there was a planned putsch against him at that time. Although party and official government documents relating to the purge were ordered destroyed by Hermann GcTring, certain materials in this category were used. Especially helpful were the Nuremberg trial records; Documents on British Foreign Policy, 1919-1939; Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918-1945; and Foreign Relations of the United States, Diplomatic Papers, 1934. Also, first-hand accounts, contem- porary reports and essays, and analytical reports of a /1J-14 secondary nature were used in researching this topic. Many memoirs, written by people in a position to observe these events, were used as well as the reports of the American, British, and French ambassadors in the German capital. -

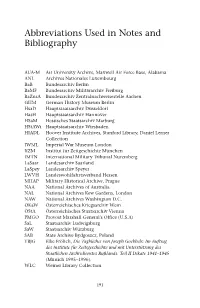

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Valkyrie-A Film Review

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 46 Number 1 Article 6 2-2010 Valkyrie-A Film Review Barry Maxfield Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Maxfield, Barry (2010) "Valkyrie-A Film Review," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 46 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol46/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Maxfield: Valkyrie-A Film Review Valkyrie-A Film Review by Barry Maxfield The Better Man Shines Forth: Valkyrie. Bryan Singer. Historical Drama. (United Artists, 2008) Cast:Tom Cruise ........................... Colonel Claus van Stauffenberg Kenneth Branagh ............ Major General Henning van Tresckow Bill Nighy ................................. General Friedrich Olbricht Tom Wilkinson ............................. General Friedrich Fromm Carice van Houten .............................. Nina van Stauffenberg It is uncommon for a historical fact to be so compelling that Hollywood would make a movie of it. It seems fictionalized history i~ the product that sells, with Saving Private Ryan being one such example it was a blending of fact and fiction into a blockbuster seller. Histor~ has accounts which are riveting yet overlooked. However, for writer Christopher McQuarrie and Nathan Alexander one of those stories camt to light, a story that could be put on celluloid and sold. The writing team has masterfully crafted a script with an eye to historical accuracy. -

United States of America V. Erhard Milch

War Crimes Trials Special List No. 38 Records of Case II United States of America v. Erhard Milch National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, Washington, D.C. 1975 Special List No. 38 Nuernberg War Crimes Trials Records of Case II United States of America v. Erhard Milch Compiled by John Mendelsohn National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1975 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data United States. National Archives and Records Service. Nuernberg war crimes trial records. (Special list - National Archives and Records Service; no. 38) Includes index. l. War crime trials--N emberg--Milch case,l946-l947. I. Mendelsohn, John, l928- II. Title. III. Series: United States. National Archives and Records Service. Special list; no.38. Law 34l.6'9 75-6l9033 Foreword The General Services Administration, through the National Archives and Records Service, is· responsible for administering the permanently valuable noncurrent records of the Federal Government. These archival holdings, now amounting to more than I million cubic feet, date from the <;lays of the First Continental Congress and consist of the basic records of the legislative, judicial, and executive branches of our Government. The presidential libraries of Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson contain the papers of those Presidents and of many of their - associates in office. These research resources document significant events in our Nation's history , but most of them are preserved because of their continuing practical use in the ordinary processes of government, for the protection of private rights, and for the research use of scholars and students. -

World War II and the Holocaust Research Topics

Name _____________________________________________Date_____________ Teacher____________________________________________ Period___________ Holocaust Research Topics Directions: Select a topic from this list. Circle your top pick and one back up. If there is a topic that you are interested in researching that does not appear here, see your teacher for permission. Events and Places Government Programs and Anschluss Organizations Concentration Camps Anti-Semitism Auschwitz Book burning and censorship Buchenwald Boycott of Jewish Businesses Dachau Final Solution Ghettos Genocide Warsaw Hitler Youth Lodz Kindertransport Krakow Nazi Propaganda Kristalnacht Nazi Racism Olympic Games of 1936 Non-Jewish Victims of the Holocaust -boycott controversy -Jewish athletes Nuremburg Race laws of 1935 -African-American participation SS: Schutzstaffel Operation Valkyrie Books Sudetenland Diary of Anne Frank Voyage of the St. Louis Mein Kampf People The Arts Germans: Terezín (Theresienstadt) Adolf Eichmann Music and the Holocaust Joseph Goebbels Swingjugend (Swing Kids) Heinrich Himmler Claus von Stauffenberg Composers Richard Wagner Symbols Kurt Weill Swastika Yellow Star Please turn over Holocaust Research Topics (continued) Rescue and Resistance: Rescue and Resistance: People Events and Places Dietrich Bonhoeffer Danish Resistance and Evacuation of the Jews Varian Fry Non-Jewish Resistance Miep Gies Jewish Resistance Oskar Schindler Le Chambon (the French town Hans and Sophie Scholl that sheltered Jewish children) Irena Sendler Righteous Gentiles Raoul Wallenburg Warsaw Ghetto and the Survivors: Polish Uprising Viktor Frankl White Rose Elie Wiesel Simon Wiesenthal Research tip - Ask: Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? questions. .