Standard Varieties of English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language, Culture, and National Identity

Language, Culture, and National Identity BY ERIC HOBSBAWM LANGUAGE, culture, and national identity is the ·title of my pa per, but its central subject is the situation of languages in cul tures, written or spoken languages still being the main medium of these. More specifically, my subject is "multiculturalism" in sofar as this depends on language. "Nations" come into it, since in the states in which we all live political decisions about how and where languages are used for public purposes (for example, in schools) are crucial. And these states are today commonly iden tified with "nations" as in the term United Nations. This is a dan gerous confusion. So let me begin with a few words about it. Since there are hardly any colonies left, practically all of us today live in independent and sovereign states. With the rarest exceptions, even exiles and refugees live in states, though not their own. It is fairly easy to get agreement about what constitutes such a state, at any rate the modern model of it, which has become the template for all new independent political entities since the late eighteenth century. It is a territory, preferably coherent and demarcated by frontier lines from its neighbors, within which all citizens without exception come under the exclusive rule of the territorial government and the rules under which it operates. Against this there is no appeal, except by authoritarian of that government; for even the superiority of European Community law over national law was established only by the decision of the constituent SOCIAL RESEARCH, Vol. -

Dialects, Standards, and Vernaculars

1 Dialects, Standards, and Vernaculars Most of us have had the experience of sitting in a public place and eavesdropping on conversations taking place around the United States. We pretend to be preoccupied, but we can’t seem to help listening. And we form impressions of speakers based not only on the topic of conversation, but on how people are discussing it. In fact, there’s a good chance that the most critical part of our impression comes from how people talk rather than what they are talking about. We judge people’s regional background, social stat us, ethnicity, and a host of other social and personal traits based simply on the kind of language they are using. We may have similar kinds of reactions in telephone conversations, as we try to associate a set of characteristics with an unidentified speaker in order to make claims such as, “It sounds like a salesperson of some type” or “It sounds like the auto mechanic.” In fact, it is surprising how little conversation it takes to draw conclusions about a speaker’s background – a sentence, a phrase, or even a word is often enough to trigger a regional, social, or ethnic classification. Video: What an accent does Assessments of a complex set of social characteristics and personality traits based on language differences are as inevitable as the kinds of judgments we make when we find out where people live, what their occupations are, where they went to school, and who their friends are. Language differences, in fact, may serve as the single most reliable indicator of social position in our society. -

The Standardisation of African Languages Michel Lafon, Vic Webb

The Standardisation of African Languages Michel Lafon, Vic Webb To cite this version: Michel Lafon, Vic Webb. The Standardisation of African Languages. Michel Lafon; Vic Webb. IFAS, pp.141, 2008, Nouveaux Cahiers de l’Ifas, Aurelia Wa Kabwe Segatti. halshs-00449090 HAL Id: halshs-00449090 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00449090 Submitted on 20 Jan 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Standardisation of African Languages Language political realities CentRePoL and IFAS Proceedings of a CentRePoL workshop held at University of Pretoria on March 29, 2007, supported by the French Institute for Southern Africa Michel Lafon (LLACAN-CNRS) & Vic Webb (CentRePoL) Compilers/ Editors CentRePoL wishes to express its appreciation to the following: Dr. Aurelia Wa Kabwe-Segatti, Research Director, IFAS, Johannesburg, for her professional and material support; PanSALB, for their support over the past two years for CentRePoL’s standardisation project; The University of Pretoria, for the use of their facilities. Les Nouveaux Cahiers de l’IFAS/ IFAS Working Paper Series is a series of occasional working papers, dedicated to disseminating research in the social and human sciences on Southern Africa. -

Normative Labels in Two Lexicographic Traditions

http://lexikos.journals.ac.za; https://doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1604 Normative Labels in Two Lexicographic Traditions: A Slovene–English Case Study Marjeta Vrbinc, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) Danko Šipka, School for International Letters and Cultures, Arizona State University, Tempe Campus, USA ([email protected]) and Alenka Vrbinc, School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) Abstract: This article presents and discusses the findings of a study conducted with the users of Slovene and American monolingual dictionaries. The aim was to investigate how native speakers of Slovene and American English interpret select normative labels in monolingual dictionaries. The data were obtained by questionnaires developed to elicit monolingual dictionary users' attitudes toward normative labels and the effects the labels have on dictionary users. The results show that a higher level of prescriptivism in the Slovene linguistic culture is reflected in the Slovene respon- dents' perception of the labels (for example, a stronger effect of the normative labels, a higher approval for the claim about usefulness of the labels, a considerably lower general level of accep- tance for the standard language) when compared with the American respondents' perception, since the American linguistic culture tends to be more descriptive. However, users often seek answers to their linguistic questions in dictionaries, which means that they expect at least a certain degree of normativity. Therefore, a balance between descriptive and prescriptive approaches should be found, since both of them affect the users. Keywords: GENERAL MONOLINGUAL DICTIONARY, PRESCRIPTIVISM, NORMATIVITY, DESCRIPTIVISM, NORMATIVE LABELS, PRIMARY EXCLUSION LABELS, SECONDARY EXCLUSION LABELS, USE OF LABELS, USEFULNESS OF LABELS, (UN)LABELED ENTRIES Opsomming: Normatiewe etikette in twee leksikografiese tradisies: 'n Sloweens–Engelse gevallestudie. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

Teaching English with a Pluricentric Approach: a Compilation of Four Upper Secondary Teachers’ Beliefs

Faculty of Education and Society Department of Culture, Languages and Media Degree Project in English Studies and Education 15 Credits, Advanced Level Teaching English with a Pluricentric Approach: a Compilation of Four Upper Secondary Teachers’ Beliefs Att undervisa i engelska med ett pluricentriskt tillvägagångssätt: en sammanställning av fyra gymnasielärares föreställningar Agnes Rauer and Elena Tizzano Master of Arts/Science in Education, 300 Credits Supervisor: Vi Thanh Son 2019-06-09 Examiner: Anna Korshin Wärnsby Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the upper secondary teachers who agreed to participate in our study, without them it would have been no study at all. We also want to thank Malin Reljanovic Glimäng for making us aware of how the English language is used in the globalized world and also for guiding our first steps in this field of research. And last but not least, we would like to thank our supervisor Vi Thanh Son for guiding and supporting us through this writing process. Contribution to the Synthesis This degree project is a result of a collaborative and equally divided effort. The research, collecting of data and the writing has been fairly distributed among the students/writers. The writing was carried out in a process made of virtual, as well as physical meetings, and facilitated by the use of Google Docs. By using this tool it was possible to follow each other’s creative process and give thorough feedback in order to improve the project. The workload was continuously discussed and adjusted throughout the writing-process and we both gained a deep knowledge of the contents of the text. -

In Britain, Standard English Is a Central Issue of Language

Copyright © Michael Stubbs 2008. This article is slightly revised from chapter 5, pp.83-97, of Michael Stubbs (1986) Educational Linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell. WHAT IS STANDARD ENGLISH? Introduction In Britain, Standard English is a central issue of language in education, since Standard English is a variety of language which can be defined only by reference to its role in the education system. It is also an example of a topic which requires careful conceptual analysis, since there is enormous confusion about terms such as 'standard', 'correct', 'proper', 'good', 'grammatical' or 'academic' English, and such terms are at the centre of much debate over English in education. A major role for linguistics is the steady unpicking of unreflecting beliefs and myths about language, especially where such beliefs affect the lives of all children in schools. Topics in language in education must be approached from four directions. 1. We need a technical linguistic description of the forms of Standard English: for example, its syntax. 2. We need a sociolinguistic theory to explain its functions: how and when it is used. 3. We need an applied analysis of planning and policy: for example, how it should be taught. 4. And we require an ideological analysis of Standard English as a major factor in the ways in which people experience power and control in their lives. Standard English has to do with passing exams, getting on in the world, respectability, prestige and success. Anyone who expresses such perceptions is also expressing an awareness of the ways in which Standard English reflects the historical and social forces which created and maintain it. -

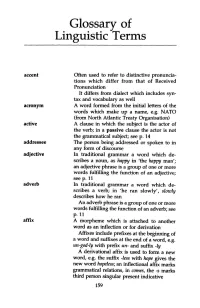

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

Attitudes Towards the Safeguarding of Minority Languages and Dialects in Modern Italy

ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE SAFEGUARDING OF MINORITY LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN MODERN ITALY: The Cases of Sardinia and Sicily Maria Chiara La Sala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Department of Italian September 2004 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to assess attitudes of speakers towards their local or regional variety. Research in the field of sociolinguistics has shown that factors such as gender, age, place of residence, and social status affect linguistic behaviour and perception of local and regional varieties. This thesis consists of three main parts. In the first part the concept of language, minority language, and dialect is discussed; in the second part the official position towards local or regional varieties in Europe and in Italy is considered; in the third part attitudes of speakers towards actions aimed at safeguarding their local or regional varieties are analyzed. The conclusion offers a comparison of the results of the surveys and a discussion on how things may develop in the future. This thesis is carried out within the framework of the discipline of sociolinguistics. ii DEDICATION Ai miei figli Youcef e Amil che mi hanno distolto -

Eight Fragments Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian

EIGHT FRAGMENTS FROM THE WORLD OF MONTENEGRIN LANGUAGES AND SERBIAN, CROATIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, BOSNIAN SERBIAN, CROATIAN, BOSNIAN AND FROM THE WORLD OF MONTENEGRIN EIGHT FRAGMENTS LANGUAGES Pavel Krejčí PAVEL KREJČÍ PAVEL Masaryk University Brno 2018 EIGHT FRAGMENTS FROM THE WORLD OF SERBIAN, CROATIAN, BOSNIAN AND MONTENEGRIN LANGUAGES Selected South Slavonic Studies 1 Pavel Krejčí Masaryk University Brno 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this e-book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission of copyright administrator which can be contacted at Masaryk University Press, Žerotínovo náměstí 9, 601 77 Brno. Scientific reviewers: Ass. Prof. Boryan Yanev, Ph.D. (Plovdiv University “Paisii Hilendarski”) Roman Madecki, Ph.D. (Masaryk University, Brno) This book was written at Masaryk University as part of the project “Slavistika mezi generacemi: doktorská dílna” number MUNI/A/0956/2017 with the support of the Specific University Research Grant, as provided by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic in the year 2018. © 2018 Masarykova univerzita ISBN 978-80-210-8992-1 ISBN 978-80-210-8991-4 (paperback) CONTENT ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................. 5 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 7 CHAPTER 1 SOUTH SLAVONIC LANGUAGES (GENERAL OVERVIEW) ............................... 9 CHAPTER 2 SELECTED CZECH HANDBOOKS OF SERBO-CROATIAN -

English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate

ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 First published in 1993 by Rhodes University Grahamstown South Africa ©PROF LS WRIGHT -1993 Laurence Wright English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate ISBN: 0-620-03155-7 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Mr Vice Chancellor, my former teachers, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen: It is a special privilege to be asked to give an inaugural lecture before the University in which my undergraduate days were spent and which holds, as a result, a special place in my affections. At his own "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" in 1866, Thomas Carlyle observed that "the true University of our days is a Collection of Books".1 This definition - beloved of university library committees worldwide - retains a certain validity even in these days of microfiche and e-mail, but it has never been remotely adequate. John Henry Newman supplied the counterpoise: . no book can convey the special spirit and delicate peculiarities of its subject with that rapidity and certainty which attend on the sympathy of mind with mind, through the eyes, the look, the accent and the manner. -

The Pronunciation of English in South Africa by L.W

The Pronunciation of English in South Africa by L.W. Lanham, Professor Emeritus, Rhodes University, 1996 Introduction There is no one, typical South African English accent as there is one overall Australian English accent. The variety of accents within the society is in part a consequence of the varied regional origins of groups of native English speakers who came to Africa at different times, and in part a consequence of the variety of mother tongues of the different ethnic groups who today use English so extensively that they must be included in the English-using community. The first truly African, native English accent in South Africa evolved in the speech of the children of the 1820 Settlers who came to the Eastern Cape with parents who spoke many English dialects. The pronunciation features which survive are mainly those from south-east England with distinct Cockney associations. The variables (distinctive features of pronunciation) listed under A below may be attributed to this origin. Under B are listed variables of probable Dutch origin reflecting close association and intermarriage with Dutch inhabitants of the Cape. There was much contact with Xhosa people in that area, but the effect of this was almost entirely confined to the vocabulary. (The English which evolved in the Eastern and Central Cape we refer to as Cape English.) The next large settlement from Britain took place in Natal between 1848 and 1862 giving rise to pronunciation variables pointing more to the Midlands and north of England (List C). The Natal settlers had a strong desire to remain English in every aspect of identity, social life, and behaviour.