Building a Navy ‘Second to None’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Gazette, 18 February, 1916. L815

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 18 FEBRUARY, 1916. L815 The undermentioned Lieutenants to be The undermentioned (Officers of the Captains: — Jamaica Contingent) to be temporary Lieu- Dated 24th January, 1916. tenants : — Raymond Stowers. Dated 7th January, 1916. Reginald O. Eades. Cyril Douglas Aubrey Robinson. Rudolph A. Peters, M.B. Frank Digby McKenzie MacPhail. Roy Sidney Martinez. Dated 10th February, 1916. Leonard Herbert Mackay. John A. Binning. Douglas Roy Ballard. Samuel Brown. Henry Fielding Donald. Kenneth Dunlop Andrews. Dated 14th February, 1916. Caryl Frederick Jacobs. James Melvin, M.B. Caryl Charles Barrett. John E. Rusby. The undermentioned (Officers of the Jamaica Contingent) to be temporary Second Lieutenants: — Dated 7th January, 1916. William Henry Kieffer. War Office, Eric Murcott Lord. 18th February, 1916. Aubrey Huntley Spyer. William Lindsay Phillips. REGULAR FORCES. John Arthur Vassall Thomson. Joseph Foley Hart. MACHINE GUN CORPS. Samuel McFarlane Foster Binns. Temporary Second Lieutenant Alfred G. Charles Howard Delgado. H. Chilvers, from The Prince of Wales's Henry Doyle O'Donnell. Own (West Yorkshire Regiment), to be tem- porary Second Lieutenant. Dated 4th Feb- Lieutenant John V. Kirkland (The West ruary, 1916. India Regiment) to be Adjutant. Dated 7th January, 1916. INFANTKY. Service Battalions. Second Reserve. The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regi- The Prince of Wales's Own (West Yorkshire ment). Regiment). Major John C. Robertson relinquishes the Temporary Captain James E. Needham temporary rank of Lieutenant-Colonel on relinquishes his commission on account of ceasing to command a Battalion. Dated ill-health. Dated 19th February, 1916. 20th August, 1915. Temporary Lieutenant - Colone! Stamer The East Surrey Regiment. Gubbins to command a Battalion, vice J. -

Alternative Naval Force Structure

Alternative Naval Force Structure A compendium by CIMSEC Articles By Steve Wills · Javier Gonzalez · Tom Meyer · Bob Hein · Eric Beaty Chuck Hill · Jan Musil · Wayne P. Hughes Jr. Edited By Dmitry Filipoff · David Van Dyk · John Stryker 1 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................ 3 The Perils of Alternative Force Structure ................................................... 4 By Steve Wills UnmannedCentric Force Structure ............................................................... 8 By Javier Gonzalez Proposing A Modern High Speed Transport – The Long Range Patrol Vessel ................................................................................................... 11 By Tom Meyer No Time To Spare: Drawing on History to Inspire Capability Innovation in Today’s Navy ................................................................................. 15 By Bob Hein Enhancing Existing Force Structure by Optimizing Maritime Service Specialization .............................................................................................. 18 By Eric Beaty Augment Naval Force Structure By Upgunning The Coast Guard .......................................................................................................... 21 By Chuck Hill A Fleet Plan for 2045: The Navy the U.S. Ought to be Building ..... 25 By Jan Musil Closing Remarks on Changing Naval Force Structure ....................... 31 By Wayne P. Hughes Jr. CIMSEC 22 www.cimsec.org -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Remembering the First World War – 1916-17 in Context Two Years Ago We Were Commemorating the Centenary of the Start of the First World War

Remembering the First World War – 1916-17 in Context Two years ago we were commemorating the centenary of the start of the First World War. In two years time in 1918, we will be commemorating its end with the centenary of the signing of the armistice in Versailles on 11 November 1918 that officially ended that dreadful four year war. This year, 2016, we will be remembering key events from the British viewpoint in 1916 and their influence on developments in 1917. However, these should be set in the broader context of the wider war, which had quickly developed into a conflict between the Triple Entente of the United Kingdom, France and Russia and the central powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy. The Military Alliances at the Start of WW1 – August 1914 Of course, things were not as clear cut as that. At the global level, Japan was an important ally of the Triple Entente throughout the war. Meanwhile in Europe, Italy changed sides in April 1915 and in June 1915 unsuccessfully attacked Austro- Hungary. By the end of August 1915, Russia had been forced out of most of Poland. After varying military successes during 1916, Russia was hit by political upheaval. In 1917 the February Revolution occurred, after which the Tsar Nicholas II abdicated. This was followed by the October Revolution when the Bolsheviks took power and signed an armistice with Germany in December 1917. In February 1915, Germany declared a submarine blockade of Great Britain and in May precipitated a diplomatic crisis with the USA by sinking the Lusitania off the coast of southern island with a loss of 1,198 lives, including 128 Americans. -

INDIANA MAGAZINE of HISTORY Volume LI JUNE,1955 Number 2

INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY Volume LI JUNE,1955 Number 2 Hoosier Senior Naval Officers in World War I1 John B. Heffermn* Indiana furnished an exceptional number of senior of- ficers to the United States Navy in World War 11, and her sons were in the very forefront of the nation’s battles, as casualty lists and other records testify. The official sum- mary of casualties of World War I1 for the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, covering officers and men, shows for Indiana 1,467 killed or died of wounds resulting from combat, 32 others died in prison camps, 2,050 wounded, and 94 released prisoners of war. There were in the Navy from Indiana 9,412 officers (of this number, probably about 6 per- cent or 555 were officers of the Regular Navy, about 10 per- cent or 894 were temporary officers promoted from enlisted grades of the Regular Navy, and about 85 percent or 7,963 were Reserve officers) and 93,219 enlisted men, or a total of 102,631. In the Marine Corps a total of 15,360 officers and men were from Indiana, while the Coast Guard had 229 offic- ers and 3,556 enlisted men, for a total of 3,785 Hoosiers. Thus, the overall Indiana total for Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard was 121,776. By way of comparison, there were about 258,870 Hoosiers in the Army.l There is nothing remarkable about the totals and Indiana’s representation in the Navy was not exceptional in quantity; but it was extraordinary in quality. -

Naval Postgraduate School Thesis

NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS A STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN ACQUISITION OF THE FRENCH MISTRAL AMPHIBIOUS ASSAULT WARSHIPS by Patrick Thomas Baker June 2011 Thesis Advisor: Mikhail Tsypkin Second Reader: Douglas Porch Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2011 Master‘s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS A Study of the Russian Acquisition of the French Mistral Amphibious Assault Warships 6. AUTHOR(S) Patrick Thomas Baker 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING N/A AGENCY REPORT NUMBER 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. -

Primary Source and Background Documents D

Note: Original spelling is retained for this document and all that follow. Appendix 1: Primary source and background documents Document No. 1: Germany's Declaration of War with Russia, August 1, 1914 Presented by the German Ambassador to St. Petersburg The Imperial German Government have used every effort since the beginning of the crisis to bring about a peaceful settlement. In compliance with a wish expressed to him by His Majesty the Emperor of Russia, the German Emperor had undertaken, in concert with Great Britain, the part of mediator between the Cabinets of Vienna and St. Petersburg; but Russia, without waiting for any result, proceeded to a general mobilisation of her forces both on land and sea. In consequence of this threatening step, which was not justified by any military proceedings on the part of Germany, the German Empire was faced by a grave and imminent danger. If the German Government had failed to guard against this peril, they would have compromised the safety and the very existence of Germany. The German Government were, therefore, obliged to make representations to the Government of His Majesty the Emperor of All the Russias and to insist upon a cessation of the aforesaid military acts. Russia having refused to comply with this demand, and having shown by this refusal that her action was directed against Germany, I have the honour, on the instructions of my Government, to inform your Excellency as follows: His Majesty the Emperor, my august Sovereign, in the name of the German Empire, accepts the challenge, and considers himself at war with Russia. -

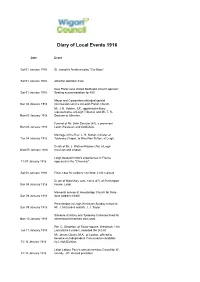

Diary of Local Events 1916

Diary of Local Events 1916 Date Event Sat 01 January 1916 St. Joseph's Amateurs play "Our Boys." Sat 01 January 1916 Atherton old folks' treat. New Plank Lane United Methodist Church opened: Sat 01 January 1916 Seating accommodation for 450. Mayor and Corporation attended special Sun 02 January 1916 intercession service at Leigh Parish Church. Mr. J. H. Holden, J.P., appointed military representative at Leigh Tribunal, and Mr. T. R. Mon 03 January 1916 Dootson at Atherton. Funeral of Mr. John Simister (61), a prominent Mon 03 January 1916 Leigh Wesleyan and Oddfellow. Marriage of the Rev. L. H. Nuttall, minister at Tue 04 January 1916 Tyldesley Chapel, to Miss Nan Sutton, of Leigh. Death of Mr. J. Watson Raynor (79), a Leigh Wed 05 January 1916 musician and clogger. Leigh despatch rider's experiences in France Fri 07 January 1916 appeared in the "Chronicle". Sat 08 January 1916 Flower day for soldiers' comforts: £140 realised Death of Miss Mary Jane Yates (47). of Pennington Sun 09 January 1916 House, Leigh. Memorial service at Howebridge Church for three Sun 09 January 1916 local soldiers (killed) Presentation at Leigh Wesleyan Sunday school to Sun 09 January 1916 Mr. J. McCardell and Mr. J. J. Taylor. Slackers at Astley and Tyldesley Collieries fined for Mon 10 January 1916 absenting themselves from work. Pte. G. Singleton, of Taylor-square, Westleigh, 11th Tue 11 January 1916 Lancashire Fusiliers, awarded the D.C.M. Mr. James Glover, M.A., of Lowton, offered to become an Independent Conservative candidate Fri 14 January 1916 for Leigh Division. -

(August 1916 and April 1918) the Black Market

Volume 5. Wilhelmine Germany and the First World War, 1890-1918 The Black Market (August 1916 and April 1918) The black market survived as the competitor to the administered food supply. The forces of supply and demand thrived here, and practically any foodstuff could be found — for a price. The prolongation of the war fed the black market to the point where it became far more than a supplement; in the estimation of authorities, Germans were purchasing one-third of all food on the black market by war’s end. I. There is no doubt that the offences mentioned here currently endanger the interests of the state to a high degree, and are also rightly perceived by the people as especially grave. A mild punishment is thus likely to provoke a feeling of uncertainty and bitterness, whereas a quick and emphatic punishment not only would deter further attempts at the dangerous practice of price- gouging; it is also likely to affect popular morale in a desirable way. II. The merchant Alfred Bürger – who is working without pay in Auxiliary Service at the Statistical Office as a special inspector for the Office of Price Review – is trying to exonerate himself by citing remarks that I made about the black market in a meeting of the Office of Price Review on February 22. My remarks were to the effect that strict measures against the commercial black market are absolutely necessary and would also be enacted in a federal law that will be passed shortly, but that small-scale black-market transactions, usually on the basis of connections among relatives or friends, are today being quietly tolerated within certain limits. -

The Myth of the Learning Curve: Tactics and Training in the 12Th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 1916-1918

Canadian Military History Volume 14 Issue 4 Article 3 2005 The Myth of the Learning Curve: Tactics and Training in the 12th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 1916-1918 Mark Osborne Humphries University of Western Ontario Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Humphries, Mark Osborne "The Myth of the Learning Curve: Tactics and Training in the 12th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 1916-1918." Canadian Military History 14, 4 (2005) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Humphries: Myth of the Learning Curve The Myth of the Learning Curve Tactics and Training in the 12th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 1916-18 Mark Osborne Humphries anadian military historians generally accept subject in the historiography. In recent years Cthat during the First World War the Canadian historians such as such as Andrew Iarocci military improved over time. This idea of a and David Campbell have begun to re-examine “learning curve” suggests that Canadians began training as a means of measuring and evaluating the war as inexperienced colonial volunteers and, the learning curve.3 This paper builds on the as the Corps gained experience on the battlefield, work of previous scholars and extends some commanders and ordinary soldiers alike learned of their arguments while challenging others. from their mistakes and successes and improved It examines the training of the 12th Canadian combat tactics from battle to battle and from Infantry Brigade for the battles of the Somme and year to year.1 Several different approaches to Amiens, as well as the official training manuals, this argument are evident in the literature. -

Tanks at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, September 1916

“A useful accessory to the infantry, but nothing more” Tanks at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, September 1916 Andrew McEwen he Battle of Flers-Courcelette Fuller was similarly unkind about the Tstands out in the broader memory Abstract: The Battle of Flers- tanks’ initial performance. In his Tanks of the First World War due to one Courcelette is chiefly remembered in the Great War, Fuller wrote that the as the combat introduction of principal factor: the debut of the tanks. The prevailing historiography 15 September attack was “from the tank. The battle commenced on 15 maligns their performance as a point of view of tank operations, not September 1916 as a renewed attempt lacklustre debut of a weapon which a great success.”3 He, too, argued that by the general officer commanding held so much promise for offensive the silver lining in the tanks’ poor (GOC) the British Expeditionary warfare. However, unit war diaries showing at Flers-Courcelette was that and individual accounts of the battle Force (BEF) General Douglas Haig suggest that the tank assaults of 15 the battle served as a field test to hone to break through German lines on September 1916 were far from total tank tactics and design for future the Somme front. Flers-Courcelette failures. This paper thus re-examines deployment.4 One of the harshest shares many familiar attributes the role of tanks in the battle from verdicts on the tanks’ debut comes with other Great War engagements: the perspective of Canadian, British from the Canadian official history. and New Zealand infantry. It finds troops advancing across a shell- that, rather than disappointing Allied It commented that “on the whole… blasted landscape towards thick combatants, the tanks largely lived the armour in its initial action failed German defensive lines to capture up to their intended role of infantry to carry out the tasks assigned to it.” a few square kilometres of barren support. -

Summer 2018 Full Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 71 Article 1 Number 3 Summer 2018 2018 Summer 2018 Full Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The .SU . (2018) "Summer 2018 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 71 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol71/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Summer 2018 Full Issue Summer 2018 Volume 71, Number 3 Summer 2018 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2018 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. 71 [2018], No. 3, Art. 1 Cover The Navy’s unmanned X-47B flies near the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roo- sevelt (CVN 71) in the Atlantic Ocean in August 2014. The aircraft completed a series of tests demonstrating its ability to operate safely and seamlessly with manned aircraft. In “Lifting the Fog of Targeting: ‘Autonomous Weapons’ and Human Control through the Lens of Military Targeting,” Merel A. C. Ekelhof addresses the current context of increas- ingly autonomous weapons, making the case that military targeting practices should be the core of any analysis that seeks a better understanding of the concept of meaningful human control.