Samuel-Krauss-Chapter1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Tamar Kadari* Abstract Julius Theodor (1849–1923)

By Tamar Kadari* Abstract This article is a biography of the prominent scholar of Aggadic literature, Rabbi Dr Julius Theodor (1849–1923). It describes Theodor’s childhood and family and his formative years spent studying at the Breslau Rabbinical Seminary. It explores the thirty one years he served as a rabbi in the town of Bojanowo, and his final years in Berlin. The article highlights The- odor’s research and includes a list of his publications. Specifically, it focuses on his monumental, pioneering work preparing a critical edition of Bereshit Rabbah (completed by Chanoch Albeck), a project which has left a deep imprint on Aggadic research to this day. Der folgende Artikel beinhaltet eine Biographie des bedeutenden Erforschers der aggadischen Literatur Rabbiner Dr. Julius Theodor (1849–1923). Er beschreibt Theodors Kindheit und Familie und die ihn prägenden Jahre des Studiums am Breslauer Rabbinerseminar. Er schil- dert die einunddreissig Jahre, die er als Rabbiner in der Stadt Bojanowo wirkte, und seine letzten Jahre in Berlin. Besonders eingegangen wird auf Theodors Forschungsleistung, die nicht zuletzt an der angefügten Liste seiner Veröffentlichungen ablesbar ist. Im Mittelpunkt steht dabei seine präzedenzlose monumentale kritische Edition des Midrasch Bereshit Rabbah (die Chanoch Albeck weitergeführt und abgeschlossen hat), ein Werk, das in der Erforschung aggadischer Literatur bis heute nachwirkende Spuren hinterlassen hat. Julius Theodor (1849–1923) is one of the leading experts of the Aggadic literature. His major work, a scholarly edition of the Midrash Bereshit Rabbah (BerR), completed by Chanoch Albeck (1890–1972), is a milestone and foundation of Jewish studies research. His important articles deal with key topics still relevant to Midrashic research even today. -

Altes Testament/Judentum Ganze, Im Zeitraum Von 30 V

439 Orientalistische Literaturzeitung 105 (2010) 4–5 440 (Kap. 7; S. 321–323) ergänzen die bisherigen Ausfüh- Arbeit von Dr. Blischke (im folgenden = Vf.), die seit rungen. Die entsprechenden Darlegungen sind weit weni- September 2007 Vikarin in der Evangelischen Kirche in ger ausführlich als die der Kapitel 3 und 4. Sie be- Mitteldeutschland ist, ihre wissenschaftliche Bedeutung schäftigen sich häufig mit allen in Tell Abu al-Kharaz innerhalb der internationalen Septuaginta-Forschung er- bezeugten Perioden und besitzen teilweise sogar nur weisen. Im deutschen Sprachgebiet wird sie umso größe- Vorberichtscharakter (S. 305). In aller Regel geben sie re Aufmerksamkeit finden, als die Veröffentlichung von nur einen ersten Einblick in die jeweiligen Gegeben- „Septuaginta Deutsch“ durch die Deutsche Bibelgesell- heiten und dienen dem Verfasser wahrscheinlich vorran- schaft in Stuttgart schon seit einiger Zeit angekündigt gig als weitere Grundlage für die im abschließenden und indessen erfolgt ist (2009). Innerhalb der Bibelwis- Kapitel (Kap. 8; S. 325–374) präsentierten sehr weit- senschaft bildet sie einen besonders schroffen Kontrast reichenden Interpretationen des Materials. zur Eschatologie neutestamentlicher Schriften2 und macht Auf insgesamt nur 50 Seiten unternimmt der Verfasser gleichzeitig noch klarer, warum die Rechtfertigung des hier den Versuch, ein umfassendes kulturhistorisches Gottlosen (Röm 4,5) das Zentrum des christlichen Glau- Gesamtbild der lokalen, regionalen und überregionalen bens ist.3 Insofern kann man von Glück sagen, dass „die Verhältnisse in und um Tell Abu al-Kharaz während der Weisheit, die von Freunden Salomos zu dessen Ehre späten Mittelbronze- und der Spätbronzezeit zu ent- geschrieben“ wurde (Canon Muratori, ca. 200 n. Chr.), werfen. Neben Aussagen zur Architektur (S. -

Geographischer Index

2 Gerhard-Mercator-Universität Duisburg FB 1 – Jüdische Studien DFG-Projekt "Rabbinat" Prof. Dr. Michael Brocke Carsten Wilke Geographischer und quellenkundlicher Index zur Geschichte der Rabbinate im deutschen Sprachgebiet 1780-1918 mit Beiträgen von Andreas Brämer Duisburg, im Juni 1999 3 Als Dokumente zur äußeren Organisation des Rabbinats besitzen wir aus den meisten deutschen Staaten des 19. Jahrhunderts weder statistische Aufstellungen noch ein zusammenhängendes offizielles Aktenkorpus, wie es für Frankreich etwa in den Archiven des Zentralkonsistoriums vorliegt; die For- schungslage stellt sich als ein fragmentarisches Mosaik von Lokalgeschichten dar. Es braucht nun nicht eigens betont zu werden, daß in Ermangelung einer auch nur ungefähren Vorstellung von Anzahl, geo- graphischer Verteilung und Rechtstatus der Rabbinate das historische Wissen schwerlich über isolierte Detailkenntnisse hinausgelangen kann. Für die im Rahmen des DFG-Projekts durchgeführten Studien erwies es sich deswegen als erforderlich, zur Rabbinatsgeschichte im umfassenden deutschen Kontext einen Index zu erstellen, der möglichst vielfältige Daten zu den folgenden Rubriken erfassen soll: 1. gesetzliche, administrative und organisatorische Rahmenbedingungen der rabbinischen Amts- ausübung in den Einzelstaaten, 2. Anzahl, Sitz und territoriale Zuständigkeit der Rabbinate unter Berücksichtigung der histori- schen Veränderungen, 3. Reihenfolge der jeweiligen Titulare mit Lebens- und Amtsdaten, 4. juristische und historische Sekundärliteratur, 5. erhaltenes Aktenmaterial -

Über Den Tieferen Wert Von Kleidung Gedanken Im Licht Der Biblischen Überlieferung

1 | Einleitung Über den tieferen Wert von Kleidung Gedanken im Licht der biblischen Überlieferung Zusammengestellt von Christoph J. Berger 1 1 | Einleitung Für alle Schwestern, die sich aus Liebe zu ihrem Erlöser keusch kleiden wollen und an alle jene Brüder und Schwestern, die sie darin nicht verstehen können. Alle Bibelstellen, soweit nicht anders angegeben, werden nach der Schlachter 2000 zitiert. Hinzufügungen in [eckigen] Klammern in Zitaten stammen vom Autor. © Mai 2020 Christoph J. Berger 2 1 | Einleitung Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 | Einleitung ............................................................................................ 6 Gottes Willen erkennen ............................................................................. 9 2 | Grundsätzliche Bedeutung von Kleidung .......................................... 14 3 | Die Geschichte der Kleidung ............................................................. 18 Kleidung zur Zeit des Alten Testaments ................................................... 18 Der Mensch macht sich Kleider (1. Mose 3,7) .................................... 18 Ein Geschenk Gottes (1. Mose 3,21) ................................................... 20 Allgemeine Hinweise (5. Mose 22) ...................................................... 21 Der Brustausschnitt Hiobs (Hiob 30,18) .............................................. 25 Sadrach, Mesach und Abednego (Daniel 3,21) ................................... 26 Und die Heiden? ................................................................................. -

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death Remi Jedwab and Noel D. Johnson and Mark Koyama⇤ April 16, 2018 Abstract We study the Black Death pogroms to shed light on the factors determining when a minority group will face persecution. In theory, negative shocks increase the likelihood that minorities are persecuted. But, as shocks become more severe, the persecution probability decreases if there are economic complementarities between majority and minority groups. The effects of shocks on persecutions are thus ambiguous. We compile city-level data on Black Death mortality and Jewish persecutions. At an aggregate level, scapegoating increases the probability of a persecution. However, cities which experienced higher plague mortality rates were less likely to persecute. Furthermore, for a given mortality shock, persecutions were less likely in cities where Jews played an important economic role and more likely in cities where people were more inclined to believe conspiracy theories that blamed the Jews for the plague. Our results have contemporary relevance given interest in the impact of economic, environmental and epidemiological shocks on conflict. JEL Codes: D74; J15; D84; N33; N43; O1; R1 Keywords: Economics of Mass Killings; Inter-Group Conflict; Minorities; Persecutions; Scapegoating; Biases; Conspiracy Theories; Complementarities; Pandemics; Cities ⇤Corresponding author: Remi Jedwab: Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, George Washington University, [email protected]. Mark Koyama: Associate -

University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich

Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. Winterthurerstr. 190 CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007 Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. THE BOOK OF JUBILEES: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY FROM THE FIRST GERMAN TRANSLATION OF 1850 TO THE ENOCH SEMINAR OF 2007 ISAAC W. OLIVER , University of Michigan VERONIKA BACHMANN , University of Zurich The following annotated bibliography provides summaries of the most influential scholarly works dedicated to the Book of Jubilees written between 1850 and 2006. * The year 1850 opens the period of modern research on Jubilees thanks to Dillmann’s translation of the Ethiopic text of Jubilees into German; the Enoch Seminar of 2007 represents the largest gathering of international scholars on the document in modern times. -

אוסף מרמורשטיין the Marmorstein Collection

אוסף מרמורשטיין The Marmorstein Collection Brad Sabin Hill THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Manchester 2017 1 The Marmorstein Collection CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on Bibliographic Citations I. Preface: Hebraica and Judaica in the Rylands -Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts: Crawford, Gaster -Printed Books: Spencer Incunabula; Abramsky Haskalah Collection; Teltscher Collection; Miscellaneous Collections; Marmorstein Collection II. Dr Arthur Marmorstein and His Library -Life and Writings of a Scholar and Bibliographer -A Rabbinic Literary Family: Antecedents and Relations -Marmorstein’s Library III. Hebraica -Literary Periods and Subjects -History of Hebrew Printing -Hebrew Printed Books in the Marmorstein Collection --16th century --17th century --18th century --19th century --20th century -Art of the Hebrew Book -Jewish Languages (Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Others) IV. Non-Hebraica -Greek and Latin -German -Anglo-Judaica -Hungarian -French and Italian -Other Languages 2 V. Genres and Subjects Hebraica and Judaica -Bible, Commentaries, Homiletics -Mishnah, Talmud, Midrash, Rabbinic Literature -Responsa -Law Codes and Custumals -Philosophy and Ethics -Kabbalah and Mysticism -Liturgy and Liturgical Poetry -Sephardic, Oriental, Non-Ashkenazic Literature -Sects, Branches, Movements -Sex, Marital Laws, Women -History and Geography -Belles-Lettres -Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine -Philology and Lexicography -Christian Hebraism -Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim Relations -Jewish and non-Jewish Intercultural Influences -

Coming to America…

Exploring Judaism’s Denominational Divide Coming to America… Rabbi Brett R. Isserow OLLI Winter 2020 A very brief early history of Jews in America • September 1654 a small group of Sephardic refugees arrived aboard the Ste. Catherine from Brazil and disembarked at New Amsterdam, part of the Dutch colony of New Netherland. • The Governor, Peter Stuyvesant, petitioned the Dutch West India Company for permission to expel them but for financial reasons they overruled him. • Soon other Jews from Amsterdam joined this small community. • After the British took over in 1664, more Jews arrived and by the beginning of the 1700’s had established the first synagogue in New York. • Officially named K.K. Shearith Israel, it soon became the hub of the community, and membership soon included a number of Ashkenazi Jews as well. • Lay leadership controlled the community with properly trained Rabbis only arriving in the 1840’s. • Communities proliferated throughout the colonies e.g. Savannah (1733), Charleston (1740’s), Philadelphia (1740’s), Newport (1750’s). • During the American Revolution the Jews, like everyone else, were split between those who were Loyalists (apparently a distinct minority) and those who supported independence. • There was a migration from places like Newport to Philadelphia and New York. • The Constitution etc. guaranteed Jewish freedom of worship but no specific “Jew Bill” was needed. • By the 1820’s there were about 3000-6000 Jews in America and although they were spread across the country New York and Charleston were the main centers. • In both of these, younger American born Jews pushed for revitalization and change, forming B’nai Jeshurun in New York and a splinter group in Charleston. -

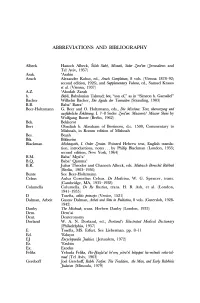

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

The Jew of Celsus and Adversus Judaeos Literature

ZAC 2017; 21(2): 201–242 James N. Carleton Paget* The Jew of Celsus and adversus Judaeos literature DOI 10.1515/zac-2017-0015 Abstract: The appearance in Celsus’ work, The True Word, of a Jew who speaks out against Jesus and his followers, has elicited much discussion, not least con- cerning the genuineness of this character. Celsus’ decision to exploit Jewish opinion about Jesus for polemical purposes is a novum in extant pagan litera- ture about Christianity (as is The True Word itself), and that and other observa- tions can be used to support the authenticity of Celsus’ Jew. Interestingly, the ad hominem nature of his attack upon Jesus is not directly reflected in the Christian adversus Judaeos literature, which concerns itself mainly with scripture (in this respect exclusively with what Christians called the Old Testament), a subject only superficially touched upon by Celsus’ Jew, who is concerned mainly to attack aspects of Jesus’ life. Why might this be the case? Various theories are discussed, and a plea made to remember the importance of what might be termed coun- ter-narrative arguments (as opposed to arguments from scripture), and by exten- sion the importance of Celsus’ Jew, in any consideration of the history of ancient Jewish-Christian disputation. Keywords: Celsus, Polemics, Jew 1 Introduction It seems that from not long after it was written, probably some time in the late 240s,1 Origen’s Contra Celsum was popular among a number of Christians. Eusebius of Caesarea, or possibly another Eusebius,2 speaks warmly of it in his response to Hierocles’ anti-Christian work the Philalethes or Lover of Truth as pro- 1 For the date of Contra Celsum see Henry Chadwick, introduction to idem, ed. -

Vixens Disturbing Vineyards

JUDAISM AND JEWISH LIFE VIXENS DISTURBING VINEYARDS: EDITORIAL BOARD EMBARRASSMENT AND EMBRACEMENT Geoffrey Alderman (University ofBuckingham, Great Britain) OF SCRIPTURES: Herbert Basser (Queens University, Canada) Donatella Ester Di Cesare (Universita "La Sapienza," Italy) Festschrift in Honor ofHarry Fox (leBeit Yoreh) Simcha Fishbane (Touro College, New York), Series Editor Meir Bar Ilan (Bar Ilan University, Israel) Andreas Nachama (Touro College, Berlin) Edited by: Tzemah Yoreh, Aubrey Glazer, Ira Robinson (Concordia University, Montreal) Justin Jaron Lewis and Miryam Segal Nissan Rubin (Bar Ilan University, Israel) Susan Starr Sered (Suffolk University, Boston) Reeva Spector Simon (Yeshiva University, New York) Boston STUDIES 2010 PRE SS A PEG TO HANG ON his .the work being "bUIlt upon DavId m terms of attnbutIOn or ascnptIOn suggests too simplistic, the hanging 0: text and upon David is not merely to call them br hIS name, but to claIm somethmg more complex about origins, dependence. and influence. Solomon's relationship to his ancestor condemns, constrains, protects, FROM GLUTTON TO GANGSTER and exalts him all at once. The great achievements of his life as understOOd Eliezer Segal, University ofCalgary by later readers - the temple and three scriptural wisdom books - are both dependent on his ancestor: the temple he built is the "Tn n':l, "house ofDaVid". • his worthiness to author the Song of Songs and Qohelet must be legitiflliucl Any list of embarrassing or morally troubling passages in the Torah must at least partly through David's merit. Solomon remains an ambivalent surely reserve an honored place for the law ofthe stubborn and rebellious son, who, in his own family drama as it unfolds through biblical interpreters, can as set out in Deuteronomy 21: 18-22. -

Reasonable Man’

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2019 The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ Johnny Sakr The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Law Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Sakr, J. (2019). The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ (Master of Philosophy (School of Law)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/215 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Conjecture from the Universality of Objectivity in Jurisprudential Thought: The Universal Presence of a ‘Reasonable Man’ By Johnny Michael Sakr Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy University of Notre Dame Australia School of Law February 2019 SYNOPSIS This thesis proposes that all legal systems use objective standards as an integral part of their conceptual foundation. To demonstrate this point, this thesis will show that Jewish law, ancient Athenian law, Roman law and canon law use an objective standard like English common law’s ‘reasonable person’ to judge human behaviour.