Guide to the Coronation Service Westminster Abbey Has Witnessed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of the Earl Marshal's Papers at Arundel

CONTENTS CONTENTS v FOREWORD by Sir Anthony Wagner, K.C.V.O., Garter King of Arms vii PREFACE ix LIST OF REFERENCES xi NUMERICAL KEY xiii COURT OF CHIVALRY Dated Cases 1 Undated Cases 26 Extracts from, or copies of, records relating to the Court; miscellaneous records concerning the Court or its officers 40 EARL MARSHAL Office and Jurisdiction 41 Precedence 48 Deputies 50 Dispute between Thomas, 8th Duke of Norfolk and Henry, Earl of Berkshire, 1719-1725/6 52 Secretaries and Clerks 54 COLLEGE OF ARMS General Administration 55 Commissions, appointments, promotions, suspensions, and deaths of Officers of Arms; applications for appointments as Officers of Arms; lists of Officers; miscellanea relating to Officers of Arms 62 Office of Garter King of Arms 69 Officers of Arms Extraordinary 74 Behaviour of Officers of Arms 75 Insignia and dress 81 Fees 83 Irregularities contrary to the rules of honour and arms 88 ACCESSIONS AND CORONATIONS Coronation of King James II 90 Coronation of King George III 90 Coronation of King George IV 90 Coronation of Queen Victoria 90 Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra 90 Accession and Coronation of King George V and Queen Mary 96 Royal Accession and Coronation Oaths 97 Court of Claims 99 FUNERALS General 102 King George II 102 Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales 102 King George III 102 King William IV 102 William Ewart Gladstone 103 Queen Victoria 103 King Edward VII 104 CEREMONIAL Precedence 106 Court Ceremonial; regulations; appointments; foreign titles and decorations 107 Opening of Parliament -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

There and Back Again: Mobilising Tourist Imaginaries at the Tower Of

There and Back Again: Mobilising Tourist Imaginaries at the Tower of London Matthew Hughes Ansell 2014 Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Cultural Heritage Studies of University College London in 2017 UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ‘Those responsible for the brochure had darkly intuited how easily their readers might be turned into prey by photographs whose power insulted the intelligence and contravened any notions of free will: over-exposed photographs of palm trees, clear skies, and white beaches. Readers who would have been capable of skepticism and prudence in other areas of their lives reverted in contact with these elements to a primordial innocence and optimism. The longing provoked by the brochure was an example, at once touching and bathetic, of how projects (and even whole lies) might be influenced by the simplest and most unexamined images of happiness; of how a lengthy and ruinously expensive journey might be set into motion by nothing more than the sight of a photograph of a palm tree gently inclining in a tropical breeze’ (de Botton 2002, 9). 2 Abstract Tourist sites are amalgams of competing and complimentary narratives that dialectically circulate and imbue places with meaning. Widely held tourism narratives, known as tourist imaginaries, are manifestations of ‘shared mental life’ (Leite 2014, 268) by tourists, would-be tourists, and not-yet tourists prior to, during, and after the tourism experience. This dissertation investigates those specific pre-tour understandings that inform tourists’ expectations and understandings of place prior to visiting. Looking specifically at the Tower of London, I employ content and discourse analysis alongside ethnographic field methods to identify the predominant tourist imaginaries of the Tower of London, trace their circulation and reproduction, and ultimately discuss their impact on visitor experience at the Tower. -

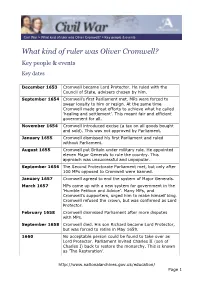

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Eagle 1909 Michaelmas

IV CONTENTS. PAGE From a Latin Hymn on St John the Evangelist Voluntaries 224 The Hymn Book 226 Halley's Comet 229 "Cornish Breakers" 236 Obituary 237 Our Chronicle 239 The Library 247 Notes tram 277 the College Records (con/iuued) In 28'i\ Memoriam : Edward VII. THE EAGLE. "By your Worship 317 and a Dymchurch Jury" St 318 Venus' Eve October Term 1909. The Rose by Other Names 328 The Book Invisible 332 Hallucinations 345 The Upper River 347 THE QUATER CENTENARY OF The New Hymn Book and 353 Certain of Our Own Poets LADY MARGARET. Epigram 354 The Hand 358 of Plato in Modern Legislation Catullus 359 [llN St Peter's day, 29 June 1909, the four hundredth anniversary of Lady Margaret's The New Window in Chapel 363 death, the Dean of Westminster preached in Commemoration Sermon 364 the Abbey at the afternoon service on our Unveiling of the New Window 377 Memorial Service 387 saintly Foundress, whose tomb, by Torrigiano, is one Reviews 389 of the jewels of the church. Obituary: 390 Near midnight a party viewed the tomb and other Rev Herbert Edward Trotter M.A. monuments by lamp-light, and the Dean distributed Rev Edwarcl Kerslake Kerslake M.A .. 396 photographs of Torrigiano's masterpiece. Richard Burton 398 Worthington M. A. At eight o'clock there met in the Jerusalem Chamber Our Chronicle 399 guests representing all the foundations of Lady Margaret, The Library 400 and all the places where she has left a name. The hosts List of Subscribers, 421 1909-10. were the Dean and Chapter of Westminster. -

Imagereal Capture

113 The Law of Arms in New Zealand: A Response Gregor Macaulay* :Noel Cox has written that "Ifany laws of arms were inherited by New Zealand, it 'was the Law of Arms of England, in 1840",1 and that in England and l'Jew Zealand today "the Law of Arms is the same in each jurisdiction",2 The statements cannot both be true; each is individually mistaken; and the English la~N of arms is in any case unworkable in New Zealand. In England, the laws of arms may be defined as the law governing "the use of anms, crests, supporters and other armorial insignia [which] is to be found in the customs and usages of the [English] Court ofChivalry",3 "augmented either by rulings of the [English] kings of arms or by warrants from the Earl Marshal [of England]".4 There are several standard reference books in English heraldry, but not even one revised and edited by a herald may, in his own words, be considered "authoritative in any official sense",5 and a definitive volume detailing the law of arms of England has never been published. A basic difficulty exists, therefore, in knowing precisely what the content of the law is that is being discussed. Even in England there are some extraordinary lacunae. For instance, the English heralds seem not to know who may legally inherit heraldic badges.6 If the English law of arms of 1840 had been inherited by New Zealand it would have come within the ambit of the English Laws Act 1858 (succeeded by the English Laws Act 1908). -

Travels of a Country Woman

Travels of a Country Woman By Lera Knox Travels of a Country Woman Travels of a Country Woman By Lera Knox Edited by Margaret Knox Morgan and Carol Knox Ball Newfound Press THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE LIBRARIES, KNOXVILLE iii Travels of a Country Woman © 2007 by Newfound Press, University of Tennessee Libraries All rights reserved. Newfound Press is a digital imprint of the University of Tennessee Libraries. Its publications are available for non-commercial and educational uses, such as research, teaching and private study. The author has licensed the work under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/>. For all other uses, contact: Newfound Press University of Tennessee Libraries 1015 Volunteer Boulevard Knoxville, TN 37996-1000 www.newfoundpress.utk.edu ISBN-13: 978-0-9797292-1-8 ISBN-10: 0-9797292-1-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2007934867 Knox, Lera, 1896- Travels of a country woman / by Lera Knox ; edited by Margaret Knox Morgan and Carol Knox Ball. xiv, 558 p. : ill ; 23 cm. 1. Knox, Lera, 1896- —Travel—Anecdotes. 2. Women journalists— Tennessee, Middle—Travel—Anecdotes. 3. Farmers’ spouses—Tennessee, Middle—Travel—Anecdotes. I. Morgan, Margaret Knox. II. Ball, Carol Knox. III. Title. PN4874 .K624 A25 2007 Book design by Martha Rudolph iv Dedicated to the Grandchildren Carol, Nancy, Susy, John Jr. v vi Contents Preface . ix A Note from the Newfound Press . xiii part I: The Chicago World’s Fair. 1 part II: Westward, Ho! . 89 part III: Country Woman Goes to Europe . -

Mary, Queen of Scots: Fact Sheet for Teachers

MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS: FACT SHEET FOR TEACHERS Mary, Queen of Scots is one of the most famous figures WHO’S WHO? in history. Her life was full of drama – from becoming queen at just six days old to her execution at the age of 44. Plots, JAMES V – Mary, Queen of Scots’ father. bloodshed, abdication, high politics, religious strife, romance He built the great tower which still survives and rivalry, Mary was a renaissance monarch who was at the Palace of Holyroodhouse. affected by and contributed to a momentous period of upheaval and uncertainty in the British Isles. MARY OF GUISE – Mary, Queen of Scots’ mother. She was French and became the regent (effectively The Palace of Holyroodhouse was one of her most the ruler) when Mary was a child and living in France. important homes, with many of the most significant events of her reign taking place within its walls. FRANCIS II – Mary, Queen of Scots’ first husband. Mary married him in 1558 when he was the Dauphin, heir to the French throne. After they married Mary gave him the title of King of Scots. He died in 1560, a year after he became King of France. WHY WAS MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS JOHN KNOX – a Protestant preacher who helped lead SO IMPORTANT? the Scottish Reformation and who was a fierce opponent of Mary because she was a Catholic and a woman ruler. She was Queen of Scots from 6 days old, and when she was an adult she became the first woman to HENRY, LORD DARNLEY – Darnely was a cousin of rule Scotland in her own right. -

EB WARD Diary

THE DIARY OF SAMUEL WARD, A TRANSLATOR OF THE 1611 KING JAMES BIBLE Transcribed and prepared by Dr. M.M. Knappen, Professor of English History, University of Chicago. Edited by John W. Cowart Bluefish Books Cowart Communications Jacksonville, Florida www.bluefishbooks.info THE DIARY OF SAMUEL WARD, A TRANSLATOR OF THE 1611 KING JAMES BIBLE. Copyright © 2007 by John W. Cowart. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America by Lulu Press. Apart from reasonable fair use practices, no part of this book’s text may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bluefish Books, 2805 Ernest St., Jacksonville, Florida, 32205. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data has been applied for. Lulu Press # 1009823. Bluefish Books Cowart Communications Jacksonville, Florida www.bluefishbooks.info SAMUEL WARD 1572 — 1643 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION …………………………………..…. 1 THE TWO SAMUEL WARDS……………………. …... 13 SAMUEL WARD’S LISTIING IN THE DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY…. …. 17 DR. M.M. KNAPPEN’S PREFACE ………. …………. 21 THE PURITAN CHARACTER IN THE DIARY. ….. 27 DR. KNAPPEN’S LIFE OF SAMUEL WARD …. …... 43 THE DIARY TEXT …………………………….……… 59 THE 1611 TRANSLATORS’ DEDICATION TO THE KING……………………………………….… 97 THE 1611 TRANSLATORS’ PREFACE TO BIBLE READERS ………………………………………….….. 101 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………….…….. 129 INTRODUCTION by John W. Cowart amuel Ward, a moderate Puritan minister, lived from 1572 to S1643. His life spanned from the reign of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth, through that of King James. and into the days of Charles I. Surviving pages of Ward’s dated diary entries run from May 11, 1595, to July 1, 1632. -

Literature Review the Outline of My Research Topic Will Encompass

Literature Review The outline of my research topic will encompass Anne of Denmark’s role as queen consort in Scotland and England, from 1589 to 1619, in order to investigate her political influence. To fully understand Anna’s political role, recent historiography surrounding influential women in early modern England and, in particular, the role of the queen consort will be evaluated in depth. My research will contribute to these two growing fields and fill a gap by re-examining Anna, who historians once considered frivolous and vain. Accompanied by re-definitions of high politics at one end of the spectrum and court masques at the other, a re-assessment of her character throughout her reign as queen consort of Scotland and England is accordingly needed. The value of analysing Anna in a political light will be demonstrated in this essay through an examination of the historiography surrounding influential women in early modern England, queen consorts in general and then Anna herself. Previous study has excluded women from high politics because it was considered part of the public sphere, rather than the private sphere that they belonged to. In her article ‘Women and Politics in Early Tudor England’, Harris challenges the traditional view of high politics by emphasising its redefinition to include the influence of women.1 Sara Mendelson and Patricia Crawford’s book, Women in Early Modern England, echoes this view. Although women exercised some influence in high politics, this is not 1 B. Harris., ‘Women and Politics in Early Tudor England’, The Historical Journal, 33:2 (1990), pp.259-281, p.259. -

Download Detailed Coronation Crown Instructions and Templates

Getty at Home Coronation Crown A crown is often bestowed as part of the inaugural ceremony (coronation) of a king or a queen as a symbol of honor and regal status. Materials: • Primary: construction paper or card stock, crayons, colored pencils, markers, paints, brushes, scissors, glue, and template (provided). • Optional: stapler, glue gun, decorative stickers, glitter, sequins, tin foil, noodles, The Coronation of the Virgin (detail), cereal, lace, pom poms, pipe cleaners, Jean Bourdichon, about 1480-1490. or cut paper shapes. You can cut or hole punch elements from old greeting cards or wrapping paper for more decorative options. Use your imagination! • Alternative: paper bag, gift bag, flattened cereal box, lightweight cardboard, or foam sheets. Tips for starting: • Gather all materials beforehand. If you don’t have the exact materials, improvise! • Use sheets measuring 8½ x 11 inches or larger for tracing the template Completed coronation crowns • Print the custom Getty crown template. © 2020 J. Paul Getty Trust Getty at Home Coronation Crown Instructions: 1. Print custom Getty template and cut out the three crown segments. 2. Decorate the printed template directly with dry media (like crayons, markers, etc.) and lightweight decorations for best results. Decorating the crown template directly 3. Or, use the template to trace three crown segments on another material like construction paper, cardstock, or cardboard 4. Cut out traced segments and decorate with crayons, markers, paints, decorative stickers, glitter, sequins, tin foil, noodles, cereal, lace, pom poms, pipe cleaners, and/or cut paper shapes. Tracing the template onto another material 5. Glue or staple the three decorated crown segments together to make one long band. -

Westminster Abbey ASERVICE to CELEBRATE the 60TH ANNIVERSARY of the CORONATION of HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH II

Westminster Abbey ASERVICE TO CELEBRATE THE 60TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE CORONATION OF HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH II Tuesday 4th June 2013 at 11.00 am FOREWORD On 2nd June 1953, the Coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II followed a pattern established over the centuries since William the Conqueror was crowned in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066. Our intention in this Service of Thanksgiving is to evoke and reflect the shape of the Coronation service itself. The Queen’s entrance was marked by the Choirs’ singing Psalm 122—I was glad—set to music for the Coronation of EdwardVII by Sir Hubert Parry. The Queen’s Scholars of Westminster School exercised their historic right to exclaim Vivat Regina Elizabetha! (‘Long live Queen Elizabeth!’); so it will be today. The coronation service begins with the Recognition. The content of this part of the service is, of course, not today what it was in 1953, but the intention is similar: to recognise with thanksgiving the dutiful service offered over the past sixty years by our gracious and noble Queen, and to continue to pray God saveThe Queen. The Anointing is an act of consecration, a setting apart for royal and priestly service, through the gift of the Holy Spirit. The Ampulla from which the oil was poured rests today on the HighAltar as a reminder of that central act. St Edward’s Crown also rests today on the High Altar as a powerful symbol of the moment of Coronation. In today’s Service, a flask of Oil is carried by representatives of the people of the United Kingdom to the Sacrarium, received by theArchbishop and placed by the Dean on the High Altar.