Literature Review the Outline of My Research Topic Will Encompass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

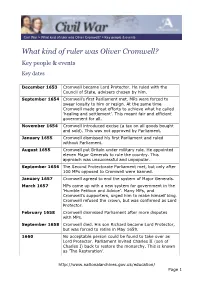

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

HENRY VII M.Elizabeth of York (R.1485–1509)

Historic Royal Places – Descriptors Small Use Width 74mm Wide and less Minimum width to be used 50mm Depth 16.5mm (TOL ) Others Various Icon 7mm Wide Dotted line for scaling Rules 0.25pt and minimum size establishment only. Does not print. HENRY VII m.Elizabeth of York (r.1485–1509) Arthur, m. Katherine HENRY VIII m.(1) Katherine m.(2) Anne m.(3) Jane m.(4) Anne of Cleves Edmund (1) James IV, m Margaret m (2) Archibald Douglas, Elizabeth Mary Catherine Prince of Wales of Aragon* (r.1509–47) Boleyn Seymour (5) Catherine Howard King of Earl of Angus (d. 1502) (6) Kateryn Parr Scotland Frances Philip II, m. MARY I ELIZABETH I EDWARD VI Mary of m. James V, Margaret m. Matthew Stewart, Lady Jane Grey King of Spain (r.1553–58) (r.1558–1603) (r.1547–53) Lorraine King of Earl of Lennox (r.1553 for 9 days) Scotland (1) Francis II, m . Mary Queen of Scots m. (2) Henry, Charles, Earl of Lennox King of France Lord Darnley Arbella James I m. Anne of Denmark (VI Scotland r.1567–1625) (I England r.1603–1625) Henry (d.1612) CHARLES I (r.1625–49) Elizabeth m. Frederick, Elector Palatine m. Henrietta Maria CHARLES II (r.1660–85) Mary m. William II, (1) Anne Hyde m. JAMES II m. (2) Mary Beatrice of Modena Sophia m. Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover m.Catherine of Braganza Prince of Orange (r.1685–88) WILLIAM III m. MARY II (r.1689–94) ANNE (r.1702–14) James Edward, GEORGE I (r.1714–27) Other issue Prince of Orange m. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Introduction: the Queen Versus the People 1

N OTES Introduction: The Queen versus the People 1 . J e a n n e L o u i s e C a m p a n , Memoirs of the Court of Marie Antoinette, Queen of France , ed. M de Lamartine (Philadelphia, PA: Parry and McMillan, 1854), pp. 158–159. 2 . Nancy Nichols Barker, “Revolution and the Royal Consort,” in Proceedings of the Consortium on Revolutionary Europe (1989): 136–143. 3 . Barker, “Revolution and the Royal Consort,” p. 136. 4 . Clarissa Campbell Orr notes in the introduction to a 2004 collection of essays concerning the role of the European queen consort in the Baroque era that “there is little comparative work in English on any facet of European Court life in the period from 1660 to 1800.” See Clarissa Campbell Orr, “Introduction” in Clarissa Campbell Orr (ed.), Queenship in Europe: 1660–1815: The Role of the Consort (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 2. There are strong exceptions to Orr’s conclusion, including the works of Jeroen Duidam and T.C.W. Blanning, which compare the culture, structure, and politics of Early Modern courts revealing both change and continuity but these stud- ies devote little space to the specific role of the queen consort within her family and court. See Jeroen Duindam, Vienna and Versailles: The Courts of Europe’s Dynastic Rivals 1550–1780 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), and T.C.W. Blanning, The Culture of Power and the Power of Culture: Old Regime Europe 1660–1789 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). 5 . See Kevin Sharpe, The Personal Rule of Charles I (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996); Bernard Bourdin, The Theological-Political Origins of the Modern State: Controversy between James I of England and Cardinal Bellamine (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2010), pp. -

The Commemorated Page Numbers in Bold Type Refer to Illustrations

Church Monuments Vols I–XXXII (1985–2017) The Commemorated Page numbers in bold type refer to illustrations Abbott, Christopher, 1686, XXIX: 80, 82 Allington, Lionel and Dorothe, 1638, V: 62, Abbys, Thomas, 1532/3, XXXII: 30 63; VII: 46, 74 Abell, William, 1500, XVI: 123 Allington, Richard, 1561, VII: 38; XXIII: 93 Aberford, Henry of, c.1328, XIII: 109 Alonso, Infante, 1493, VII: 27 Abernoun, John d’, 1327, I: 10; VI: 5; VIII: 5, Alphonse and Jean, sons of Louis VIII, king of 7; IX: 38; XV: 12 France, 1213, XXX: 51 Abernoun, John III d’, 1335–50, II: 13, 17–19; Alsace, Marguerite d’, 1194, XXIV: 28, 29, VII: 17 30, 31, 43 Abney, George and Ellen, 1577/8, VI: 38 Alsace, Mathieu d’, 1173, XXIV: 31, 33, 36, Accarigi, Tommaso, XXIII: 110 38 Acé, Hugues d’, 1333, XII: 23, 24, 33 Anast, Thomas d’, bishop of Quimper, 1322, Achard, Robert, 1353, IX: 46; XXXII: 24 XXX: 45 Acton, John and Elizabeth, 1625, XXIII: 81 Ancaster see Bertie Acton, Thomas, 1489, XXXII: 30 Anderson, Alexander, 1811, XV: 99 Adair family, 1852–1915, XVI: 92, 123 Anderson, Edmond, 1638, XXX: 129, 130 Adams, Richard, 1635, XXIX: 75 Anderson, Edmund, 1670, IX: 84, 85, 86 Adderley, Ralph, Margaret and Philota, 1595, Anderson, Francis, VII: 89, 90, 91, 93 VI: 40 André, Philippe and Marie, 1845, XV: 91, 93, Adelaide of Maurienne, queen of France, 1154, 96 XIX: 34 Andrew, Thomas, Frances and Mary, 1589, Adornes, Jacques, 1482, VII: 28 VIII: 54 Adyn, Edith, c.1560, XXIX: 82 Andrew, Thomas, Katherine and Mary, 1555, Aebinga, Hil van, XXXI: 118 n. -

French Revolution and English Revolution Comparison Chart Print Out

Socials 9 Name: Camilla Mancia Comparison of the English Revolution and French Revolution TOPIC ENGLISH REVOLUTION FRENCH REVOLUTION SIMILARITIES DIFFERENCES 1625-1689 Kings - Absolute monarchs - Absolute monarchs - Kings ruled as Absolute - English Kings believed in Divine - James I: intelligent; slovenly - Louis XIV: known as the “Sun King”; Monarchs Right of Kings and French did habits; “wisest fool in saw himself as center of France and - Raised foreign armies not Christendom”; didn’t make a forced nobles to live with him; - Charles I and Louis XVI both - Charles I did not care to be good impression on his new extravagant lifestyle; built Palace of did not like working with loved whereas Louis XVI initially subjects; introduced the Divine Versailles ($$) Parliament/Estates General wanted to be loved by his people Right Kings - Louis XV: great grandson of Louis XIV; - Citizens did not like the wives of - Charles I did not kill people who - Charles I: Believed in Divine only five years old when he became Charles I (Catholic) and Louis were against him (he Right of Kings; unwilling to King; continued extravagances of the XVI (from Austria) imprisoned or fined them) compromise with Parliament; court and failure of government to - Both Charles I and Louis XVI whereas Louis XVI did narrow minded and aloof; lived reform led France towards disaster punished critics of government - Charles I called Lord Strafford, an extravagant life; Wife - Louis XVI; originally wanted to be Archbishop Laud and Henrietta Maria and people loved; not interested -

Henrietta Maria: the Betrayed Queen

2018 V Henrietta Maria: The Betrayed Queen Dominic Pearce Stroud: Amberley, 2015 Review by: Andrea Zuvich Review: Henrietta Maria: The Betrayed Queen Henrietta Maria: The Betrayed Queen. By Dominic Pearce. Stroud: Amberley, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4456-4547-6. 352 pp. £20. enrietta Maria, the controversial uncrowned queen consort of the equally provocative Charles I of England, Scotland, and Ireland, H continues to have a reputation for shrewish obstinacy and religious bigotry, with little—if any—attention given to the more positive qualities of her character. The premise behind Dominic Pearce’s biography is that historians have betrayed the queen, because she has been largely ignored and/or disrespected. Pearce shows Henrietta Maria as a fully-fleshed person: her weaknesses and strengths are equally stated. The text is followed by a list of Henrietta Maria’s descendants, notes, a bibliography, acknowledgements, and an index. The 2010s have seen a positive trend in biographies seeking to re- examine the Stuart monarchs of the seventeenth century, notably Mark Kishlansky’s Charles I: An Abbreviated Life (2014), and White King: Charles I – Traitor, Murderer, Martyr by Leanda de Lisle (2018). Such critical re-evaluations have led to studies that are more balanced and more aware of the complexities of the figures of the seventeenth-century Stuart dynasty than the prejudices of Whig historians have previously allowed. Pearce’s book is no exception and, while it competently adds to the scholarship of the Caroline period, it perhaps can be argued that it does not add a great deal more than what has already been written in other relatively recent works on or featuring Henrietta Maria, such as Alison Plowden’s Henrietta Maria: Charles I’s Indomitable Queen (2001), or Katie Whitaker’s A Royal Passion: The Turbulent Marriage of King Charles I of England and Henrietta Maria of France (2010). -

Copyrighted Material

33_056819 bindex.qxp 11/3/06 11:01 AM Page 363 Index fighting the Vikings, 52–54 • A • as law-giver, 57–58 Aberfan tragedy, 304–305 literary interests, 56–57 Act of Union (1707), 2, 251 reforms of, 54–55 Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen of reign of, 50, 51–52 William IV, 268, 361 Alfred, son of King Aethelred, king of Áed, king of Scotland, 159 England, 73, 74 Áed Findliath, ruler in Ireland, 159 Ambrosius Aurelianus (Roman leader), 40 Aedán mac Gabráin, overking of Dalriada, 153 Andrew, Prince, Duke of York (son of Aelfflaed, queen of Edward, king Elizabeth II) of Wessex, 59 birth of, 301 Aelfgifu of Northampton, queen of Cnut, 68 as naval officer, 33 Aethelbald, king of Mercia, 45 response to death of Princess Diana, 313 Aethelbert, king of Wessex, 49 separation from Sarah, Duchess of York, Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred, king of 309 Wessex, 46 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 57, 58, 63 Aethelfrith, Saxon king, 43 Anglo-Saxons Aethelred, king of England, 51, 65–66 appointing an heir, 16 Aethelred, king of Mercia, 45, 46, 55 invasion of Britain, 39–41 Aethelred, king of Wessex, 50 kingdoms of, 37, 42 Aethelstan, king of Wessex, 51, 61–62 kings of, 41–42 Aethelwold, son of Aethelred, king of overview, 12 Wessex, 60 Anna, queen of Scotland, 204 Aethelwulf, king of Wessex, 49 Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of Africa, as part of British empire, 14 Elizabeth II, 301, 309 Agincourt, battle of, 136–138 Anne, queen of England Albert, Prince, son of George V, later lack of heir, 17 George VI, 283, 291 marriage to George of Denmark, 360–361 Albert of -

Mary, Queen of Scots: Fact Sheet for Teachers

MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS: FACT SHEET FOR TEACHERS Mary, Queen of Scots is one of the most famous figures WHO’S WHO? in history. Her life was full of drama – from becoming queen at just six days old to her execution at the age of 44. Plots, JAMES V – Mary, Queen of Scots’ father. bloodshed, abdication, high politics, religious strife, romance He built the great tower which still survives and rivalry, Mary was a renaissance monarch who was at the Palace of Holyroodhouse. affected by and contributed to a momentous period of upheaval and uncertainty in the British Isles. MARY OF GUISE – Mary, Queen of Scots’ mother. She was French and became the regent (effectively The Palace of Holyroodhouse was one of her most the ruler) when Mary was a child and living in France. important homes, with many of the most significant events of her reign taking place within its walls. FRANCIS II – Mary, Queen of Scots’ first husband. Mary married him in 1558 when he was the Dauphin, heir to the French throne. After they married Mary gave him the title of King of Scots. He died in 1560, a year after he became King of France. WHY WAS MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS JOHN KNOX – a Protestant preacher who helped lead SO IMPORTANT? the Scottish Reformation and who was a fierce opponent of Mary because she was a Catholic and a woman ruler. She was Queen of Scots from 6 days old, and when she was an adult she became the first woman to HENRY, LORD DARNLEY – Darnely was a cousin of rule Scotland in her own right. -

Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019

16 March — 14 July 2019 British Royal Portraits Exhibition organised by the National Portrait Gallery, London Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019 Tudors to Windsors traces the history of the British monarchy through the outstanding collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. This exhibition highlights major events in British (and world) history from the sixteenth century to the present, examining the ways in which royal portraits were impacted by both the personalities of individual monarchs and wider historical change. Presenting some of the most significant royal portraits, the exhibition will explore five royal dynasties: the Tudors, the Stuarts, the Georgians, the Victorians and the Windsors shedding light on key figures and important historical moments. This exhibition also offers insight into the development of British art including works by the most important artists to have worked in Britain, from Sir Peter Lely and Sir Godfrey Kneller to Cecil Beaton and Annie Leibovitz. 2 UK WORLDWIDE 1485 Henry Tudor defeats Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field, becoming King Henry VII The Tudors and founding the Tudor dynasty 1492 An expedition led by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus encounters the Americas 1509 while searching for a Western passage to Asia Henry VII dies and is succeeded Introduction by King Henry VIII 1510 The Inca abandon the settlement of Machu Picchu in modern day Peru Between 1485 and 1603, England was ruled by 1517 Martin Luther nails his 95 theses to the five Tudor monarchs. From King Henry VII who won the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, crown in battle, to King Henry VIII with his six wives and a catalyst for the Protestant Reformation 1519 Elizabeth I, England’s ‘Virgin Queen’, the Tudors are some Hernando Cortes lands on of the most familiar figures in British history. -

Monarchs During Feudal Times

Monarchs During Feudal Times At the very top of feudal society were the monarchs, or kings and queens. As you have learned, medieval monarchs were also feudal lords. They were expected to keep order and to provide protection for their vassals. Most medieval monarchs believed in the divine right of kings, the idea that God had given them the right to rule. In reality, the power of monarchs varied greatly. Some had to work hard to maintain control of their kingdoms. Few had enough wealth to keep their own armies. They had to rely on their vassals, especially nobles, to provide enough knights and soldiers. In some places, especially during the Early Middle Ages, great lords grew very powerful and governed their fiefs as independent states. In these cases, the monarch was little more than a figurehead, a symbolic ruler who had little real power. In England, monarchs became quite strong during the Middle Ages. Since the Roman period, a number of groups from the continent, including Vikings, had invaded and settled England. By the mid11th century, it was ruled by a Germanic tribe called the Saxons. The king at that time was descended from both Saxon and Norman (French) families. When he died without an adult heir, there was confusion over who should become king. William, the powerful Duke of Normandy (a part of presentday France), believed he had the right to the English throne. However, the English crowned his cousin, Harold. In 1066, William and his army invaded England. William defeated Harold at the Battle of Hastings and established a line of Norman kings in England.