Ana Turri Gimilli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuneiform Digital Library Preprints <

Cuneiform Digital Library Preprints <http://cdli.ucla.edu/?q=cuneiform-digital-library-preprints> Hosted by the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (<http://cdli.ucla.edu>) Editor: Bertrand Lafont (CNRS, Nanterre) Number 6 Title: „Nachdem das Königtum vom Himmel herabgekommen war…“. Untersuchungen zur Sumerischen Königliste. Author: Jörg Kaula Posted to web: 21 November 2016 „NACHDEM DAS KÖNIGTUM VOM HIMMEL HERABGEKOMMEN WAR…“ Untersuchungen zur Sumerischen Königsliste Von Jörg Kaula 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Die Tonprismen der Weld-Blundell-Collection im Ashmolean Museum in Oxford 5 2 Königslisten in der Keilschriftliteratur 6 3 Die Sumerische Königsliste 7 3.1 Die „antediluvian section“ 11 3.2 Die Ur – Isin-Königsliste 12 3.3 Der Kern der Sumerischen Königsliste 12 4 Die SKL in der Forschung 14 5 Die Bedeutung der Zahlen 17 6 Das Umfeld und der Sinn der SKL 22 7 Das Königtum 23 8 Die Genesis der SKL von Naram-Sîn bis zu den Königen von Isin 24 9 Die Rekonstruktion des Weld-Blundell-Prismas 26 10 Die Sumerische Königliste – Transliteration 28 11 Deutsche Übersetzung 44 12 Kommentar zur Rekonstruktionsfassung 54 13 Literaturverzeichnis 69 4 Abstract The duration of the First Dynasty of Kish, 24510 years as provided by the Sumerian King List (SKL), is generally held as a purely mythical account without any historical reliability. However, a careful examination of the SKL’s most complete version in the Weld-Blundell Prism (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, inv. no.WB. 1923.444) not only allows us to reconstruct the text itself by completing lost parts by some other recently published versions of the SKL. Also we get some further insight into the metrological system used by the authors of the SKL. -

Effect of Marine Bacillus BC-2 on the Health-Beneficial Ingredients of Flavor Liquor

Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2019, 10, 606-612 http://www.scirp.org/journal/fns ISSN Online: 2157-9458 ISSN Print: 2157-944X Effect of Marine Bacillus BC-2 on the Health-Beneficial Ingredients of Flavor Liquor Yueming Li*, Jianchun Xu, Zhimei Xu Qingdao Langyatai Group Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China How to cite this paper: Li, Y.M., Xu, J.C. Abstract and Xu, Z.M. (2019) Effect of Marine Ba- cillus BC-2 on the Health-Beneficial Ingre- The main aroma component of Luzhou-flavor Liquor is ethyl caproate, which dients of Flavor Liquor. Food and Nutrition is combined with appropriate amount of ethyl butyrate, ethyl acetate, ethyl Sciences, 10, 606-612. lactate and so on. By adding the marine bacillus BC-2 (Accession number: https://doi.org/10.4236/fns.2019.106044 MK811408) to substrate sludge, the bacillus complex bacterial liquid (pit Mud Received: March 27, 2019 Functional Bacterial liquid) has been modified. The complex bacterial liquid Accepted: June 11, 2019 was used in the production of Luzhou-flavor Liquor and it dramatically pro- Published: June 14, 2019 moted the content of health-beneficial ingredients in the new workshop. These results demonstrated that the marine bacillus BC-2 can effectively im- Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and prove the quality and health benefit of Luzhou-flavor Liquor. Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Keywords License (CC BY 4.0). Luzhou-Flavor Liquor, Marine Bacillus BC-2, Flavoring Components http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Open Access 1. Introduction In China, Luzhou-flavor Liquor is the most widely used Luzhou-flavor Liquor in social intercourse and its taste is closely related to the quality of pit mud. -

Archaeological Observation on the Exploration of Chu Capitals

Archaeological Observation on the Exploration of Chu Capitals Wang Hongxing Key words: Chu Capitals Danyang Ying Chenying Shouying According to accurate historical documents, the capi- In view of the recent research on the civilization pro- tals of Chu State include Danyang 丹阳 of the early stage, cess of the middle reach of Yangtze River, we may infer Ying 郢 of the middle stage and Chenying 陈郢 and that Danyang ought to be a central settlement among a Shouying 寿郢 of the late stage. Archaeologically group of settlements not far away from Jingshan 荆山 speaking, Chenying and Shouying are traceable while with rice as the main crop. No matter whether there are the locations of Danyang and Yingdu 郢都 are still any remains of fosses around the central settlement, its oblivious and scholars differ on this issue. Since Chu area must be larger than ordinary sites and be of higher capitals are the political, economical and cultural cen- scale and have public amenities such as large buildings ters of Chu State, the research on Chu capitals directly or altars. The site ought to have definite functional sec- affects further study of Chu culture. tions and the cemetery ought to be divided into that of Based on previous research, I intend to summarize the aristocracy and the plebeians. The relevant docu- the exploration of Danyang, Yingdu and Shouying in ments and the unearthed inscriptions on tortoise shells recent years, review the insufficiency of the former re- from Zhouyuan 周原 saying “the viscount of Chu search and current methods and advance some personal (actually the ruler of Chu) came to inform” indicate that opinion on the locations of Chu capitals and later explo- Zhou had frequent contact and exchange with Chu. -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

Cuneiform Monographs

VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page ii Cuneiform Monographs Editors t. abusch ‒ m.j. geller s.m. maul ‒ f.a.m. wiggerman VOLUME 35 frontispiece 4/26/06 8:09 PM Page ii Stip (Dr. H. L. J. Vanstiphout) VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page iii Approaches to Sumerian Literature Studies in Honour of Stip (H. L. J. Vanstiphout) Edited by Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on http: // catalog.loc.gov ISSN 0929-0052 ISBN-10 90 04 15325 X ISBN-13 978 90 04 15325 7 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page v CONTENTS Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis H. L. J. Vanstiphout: An Appreciation .............................. 1 Publications of H. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

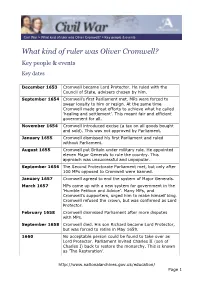

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

The Sumerian King List the Sumerian King List (SKL) Dates from Around 2100 BCE—Near the Time When Abram Was in Ur

BcResources Genesis The Sumerian King List The Sumerian King List (SKL) dates from around 2100 BCE—near the time when Abram was in Ur. Most ANE scholars (following Jacobsen) attribute the original form of the SKL to Utu-hejel, king of Uruk, and his desire to legiti- mize his reign after his defeat of the Gutians. Later versions included a reference or Long Chronology), 1646 (Middle to the Great Flood and prefaced the Chronology), or 1582 (Low or Short list of postdiluvian kings with a rela- Chronology). The following chart uses tively short list of what appear to be the Middle Chronology. extremely long-reigning antediluvian Text. The SKL text for the following kings. One explanation: transcription chart was originally in a narrative form or translation errors resulting from and consisted of a composite of several confusion of the Sumerian base-60 versions (see Black, J.A., Cunningham, and the Akkadian base-10 systems G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., of numbering. Dividing each ante- and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text diluvian figure by 60 returns reigns Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http:// in harmony with Biblical norms (the www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/), Oxford bracketed figures in the antediluvian 1998-). The text was modified by the portion of the chart). elimination of manuscript references Final versions of the SKL extended and by the addition of alternative the list to include kings up to the reign name spellings, clarifying notes, and of Damiq-ilicu, king of Isin (c. 1816- historical dates (typically in paren- 1794 BCE). thesis or brackets). The narrative was Dates. -

{PDF} Ancient Civilizations the Near East and Mesoamerica 2Nd Edition

ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS THE NEAR EAST AND MESOAMERICA 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK C C Lamberg-Karlovsky | 9780881338348 | | | | | Ancient Civilizations The near East and Mesoamerica 2nd edition PDF Book Thanks to their artwork, we have a very good idea of how they looked: men of short stature, but with muscular bodies, that shaved their faces and heads. Their known homeland was centred on Subartu , the Khabur River valley, and later they established themselves as rulers of small kingdoms throughout northern Mesopotamia and Syria. Add to Wishlist. They are the most striking constructions in their monumental funerary complex, the position of which symbolized the journey of the deceased ruler to the western realm of the dead. The River Nile was the center of Egyptian life. Rating details. Later dynasties promoted the worship of Ra, the solar god who ruled the world. Deanne rated it really liked it Feb 15, Scholars even have used the term 'Aramaization' for the Assyro-Babylonian peoples' languages and cultures, that have become Aramaic-speaking. Laurelyn Anne added it Oct 23, It has Nefertiti on the front, need I say more? Luwian was also the language spoken in the Neo-Hittite states of Syria , such as Melid and Carchemish , as well as in the central Anatolian kingdom of Tabal that flourished around BC. Priests were seers who predicted the future, acted as oracles, explained dreams, and offered sacrifices. The great Sumerian invention was cuneiform writing, which made it possible to share their thoughts and the events that affected them with future generations. A'annepada Meskiagnun Elulu Balulu. Rick rated it it was amazing Oct 19, Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt Achaemenid conquest of Egypt. -

Ancient Mesopotamia Akkdadian Empire Reading Comprehension

ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA AKKDADIAN EMPIRE READING COMPREHENSION *Article *10 Matching Questions *10 True/False Questions *4 Multiple Choice Questions *Key Included Name____________________ ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA- AKKADIAN EMPIRE The Akkadian Empire was the first Empire to rule all of Mesopotamia. It lasted about 200 years from 2300 BC to 2100 BC. Originally the Sumerians lived in the southern part of Mesopotamia and the Akkadians lived in the northern part. They had similar governments and cultures, but spoke different languages. The governments had individual city-states, where each city had its own ruler that controlled the city and the surrounding area. The city-states were not initially united and often warred with one another. Eventually, the Akkadian rulers started to see the advantage to uniting many of their cities under a single nation and began forming alliances to work together. Sargon the Great rose to power around 2300 BC. According to Sumerian literature, Sargon was born to an Akkadian high priestess and a poor father, maybe a gardener. His mother abandoned him by putting him a reed woven basket and let it float down the river, like Moses a thousand years later. Sargon was rescued and made friends with the goddess Ishtar and was brought up in the king’s court. Sargon built himself a new city at Akkad and made himself the king of it when he grew up. He gradually conquered all the land around it, making the Akkadian Empire. The powerful Sumerian city of Uruk attacked Akkad, but they fought back and eventually conquered Uruk. Sargon went on to conquer all of the Sumerian city-states and united northern and southern Mesopotamia under a single ruler. -

Gilgamesh Sung in Ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East

Gilgamesh sung in ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East Dr. Le4cia R. Rodriguez 20.09.2017 ì The Ancient Near East Cuneiform cuneus = wedge Anadolu Medeniyetleri Müzesi, Ankara Babylonian deed of sale. ca. 1750 BCE. Tablet of Sargon of Akkad, Assyrian Tablet with love poem, Sumerian, 2037-2029 BCE 19th-18th centuries BCE *Gilgamesh was an historic figure, King of Uruk, in Sumeria, ca. 2800/2700 BCE (?), and great builder of temples and ci4es. *Stories about Gilgamesh, oral poems, were eventually wriXen down. *The Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh compiled from 73 tablets in various languages. *Tablets discovered in the mid-19th century and con4nue to be translated. Hero overpowering a lion, relief from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad), Iraq, ca. 721–705 BCE The Flood Tablet, 11th tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Library of Ashurbanipal Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BCE, The Bri4sh Museum American Dad Gilgamesh and Enkidu flank the fleeing Humbaba, cylinder seal Neo-Assyrian ca. 8th century BCE, 2.8cm x 1.3cm, The Bri4sh Museum DOUBLING/TWINS BROMANCE *Role of divinity in everyday life. *Relaonship between divine and ruler. *Ruler’s asser4on of dominance and quest for ‘immortality’. StatuePes of two worshipers from Abu Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), Iraq, ca. 2700 BCE. Gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone, male figure 2’ 6” high. Iraq Museum, Baghdad. URUK (WARKA) Remains of the White Temple on its ziggurat. Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. 3500–3000 BCE. Plan and ReconstrucVon drawing of the White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. -

Discovering Discrepancies in Numerical Libraries

Discovering Discrepancies in Numerical Libraries Jackson Vanover Xuan Deng Cindy Rubio-González University of California, Davis University of California, Davis University of California, Davis United States of America United States of America United States of America [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT libraries aim to offer a certain level of correctness and robustness in Numerical libraries constitute the building blocks for software appli- their algorithms. Specifically, a discrete numerical algorithm should cations that perform numerical calculations. Thus, it is paramount not diverge from the continuous analytical function it implements that such libraries provide accurate and consistent results. To that for its given domain. end, this paper addresses the problem of finding discrepancies be- Extensive testing is necessary for any software that aims to be tween synonymous functions in different numerical libraries asa correct and robust; in all application domains, software testing means of identifying incorrect behavior. Our approach automati- is often complicated by a deficit of reliable test oracles and im- cally finds such synonymous functions, synthesizes testing drivers, mense domains of possible inputs. Testing of numerical software and executes differential tests to discover meaningful discrepan- in particular presents additional difficulties: there is a lack of stan- cies across numerical libraries. We implement our approach in a dards for dealing with inevitable numerical errors, and the IEEE 754 tool named FPDiff, and provide an evaluation on four popular nu- Standard [1] for floating-point representations of real numbers in- merical libraries: GNU Scientific Library (GSL), SciPy, mpmath, and herently introduces imprecision. As a result, bugs are commonplace jmat.