From Label to Practice: the Process of Creating New Nordic Cuisine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Catalog

THE TOMTEN CATALOG 2020 - 2021 Cover photo by Maria Anderhell from Splendor of Sweden 2021 calendar (see back cover). NOTECARDS & BOOKS BY KIRSTEN SEVIG STRIPED PEAR STUDIO is a card line by Kirsten Sevig, focused on creating high-quality, earth-friendly, and locally-made paper products. These unique cards are fresh and fun! Kirsten is an illustrator who loves to blank pages. To see what Kirsten’s working on now, follow her on Instagram. @kirstensevig Printed on textured recycled paper, the designs on all of the notecards in these collections wrap around the front and back of each card, and the insides are blank. Additional gift enclosure cards available online. View all of the cards in each collection on our website: www.skandisk.com Card size: 4.5" x 6" Each collection includes: 8 cards • 4 designs • 8 envelopes $13.95 each Itty Bitty Goat Notes Hygge Enclosure Cards 10 cards, 2 designs. 10 cards, 2 designs. Design wraps around card. Design wraps around card. No envelopes. 2.25" x 3" No envelopes. 2.25" x 3" $6.95 CRD 635 $6.95 CRD 639 8.5" x 2.25" Goat Notes Goat Bookmark $1.25 NOV 121 Hygge Notecards Garden Notecards CRD 634 CRD 638 CRD 632 Back in stock! Winter Enclosure Cards 8.5" 10 cards, 2 designs. x 2.25" Design wraps around card. No envelopes. 2.25" x 3" Up North Reykjavík Notecards Flora Notecards Woodland Notecards Winter Notecards $6.95 CRD 627 Bookmark CRD 620 CRD 622 CRD 624 CRD 626 $1.25 NOV 122 NOTECARDS & REUSABLE BAGS WITH KIRSTEN’S CATS & DOGS! GOAT BAGS COMING MARCH 2021! Goat LOVE Sack $17.95 Dog Stash-It NOV 211 Bag $19.95 NOV 205 Cat Lover Notecards Dog Lover Notecards Cat LOVE Sack $13.95 CRD 628 $13.95 CRD 630 $17.95 NOV 201 Made from recycled Goat Stash-It plastic bottles! Bag $19.95 NOV 210 Stash-It Bags It’s not just a cute bag! It’s meant to change the way you think about bags. -

Aquaponics NOMA New Innovations for Sustainable Aquaculture in the Nordic Countries

NORDIC INNOVATION PUBLICATION 2015:06 // MAY 2015 Aquaponics NOMA New Innovations for Sustainable Aquaculture in the Nordic Countries Aquaponics NOMA (Nordic Marine) New Innovations for Sustainable Aquaculture in the Nordic Countries Author(s): Siv Lene Gangenes Skar, Bioforsk Norway Helge Liltved, NIVA Norway Paul Rye Kledal, IGFF Denmark Rolf Høgberget, NIVA Norway Rannveig Björnsdottir, Matis Iceland Jan Morten Homme, Feedback Aquaculture ANS Norway Sveinbjörn Oddsson, Matorka Iceland Helge Paulsen, DTU-Aqua Denmark Asbjørn Drengstig, AqVisor AS Norway Nick Savidov, AARD, Canada Randi Seljåsen, Bioforsk Norway May 2015 Nordic Innovation publication 2015:06 Aquaponics NOMA (Nordic Marine) – New Innovations for Sustainable Aquaculture in the Nordic Countries Project 11090 Participants Siv Lene Gangenes Skar, Bioforsk/NIBIO Norway, [email protected] Helge Liltved, NIVA/UiA Norway, [email protected] Asbjørn Drengstig, AqVisor AS Norway, [email protected] Jan M. Homme, Feedback Aquaculture Norway, [email protected] Paul Rye Kledal, IGFF Denmark, [email protected] Helge Paulsen, DTU Aqua Denmark, [email protected] Rannveig Björnsdottir, Matis Iceland, [email protected] Sveinbjörn Oddsson, Matorka Iceland, [email protected] Nick Savidov, AARD Canada, [email protected] Key words: aquaponics, bioeconomy, recirculation, nutrients, mass balance, fish nutrition, trout, plant growth, lettuce, herbs, nitrogen, phosphorus, business design, system design, equipment, Nordic, aquaculture, horticulture, RAS. Abstract The main objective of AQUAPONICS NOMA (Nordic Marine) was to establish innovation networks on co-production of plants and fish (aquaponics), and thereby improve Nordic competitiveness in the marine & food sector. To achieve this, aquaponics production units were established in Iceland, Norway and Denmark, adapted to the local needs and regulations. -

Eating the North: an Analysis of the Cookbook NOMA: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine Author(S): L

Title: Eating the North: An Analysis of the Cookbook NOMA: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine Author(s): L. Sasha Gora Source: Graduate Journal of Food Studies, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Nov. 2017) Published by: Graduate Association for Food Studies ©Copyright 2017 by the Graduate Association for Food Studies. The GAFS is a graduate student association that helps students doing food-related work publish and gain professionalization. For more information about the GAFS, please see our website at https://gradfoodstudies.org/. L. SASHA GORA Eating the North: An Analysis of the Cookbook NOMA: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine abstract | A portmanteau of the Danish words nordisk (Nordic) and mad (food), Noma opened in Copenhagen, Denmark in 2003. Seven years later, it was crowned first in Restaurant Magazine’s Best Restaurant in the World competition. That same year, 2010, the restaurant published its first English cookbook NOMA: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine, authored by chef René Redzepi. In this article I analyze this cookbook, focusing on how the visuals, texts, and recipes signify time and place for diverse publics. I begin with a literature review—discussing cookbooks as tools of communication and marketing—and consider the role the visual plays in this process. How does the cookbook represent Nordic food and the region from which it comes? How does the composition of the book as a whole shape not only what is considered Nordic food, but also the Nordic region? I then closely read NOMA: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine, demonstrating how the cookbook does not represent a time and place, but instead constructs one. -

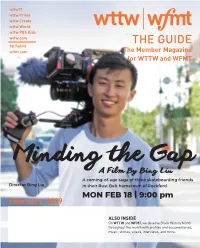

Inside the Guide the Guide

wttw11 wttw Prime wttw Create wttw World wttw PBS Kids wttw.com THE GUIDE 98.7wfmt wfmt.com The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT A coming-of-age saga of three skateboarding friends Director Bing Liu in their Rust Belt hometown of Rockford. MON FEB 18 | 9:00 pm February 2019 ALSO INSIDE On WTTW and WFMT, we observe Black History Month throughout the month with profiles and documentaries, music, stories, videos, interviews, and more. From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Greetings from WTTW and WFMT. This month, we are excited to bring you Chicago, Illinois 60625 the acclaimed documentary about the life of a public media treasure and icon – Mister Fred Rogers. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? premieres on WTTW11 on Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 February 9. Join us for an in-depth and entertaining look at the life of a visionary Member and Viewer Services who fostered compassion and curiosity in generations of children and families. (773) 509-1111 x 6 February is also Black History Month, and we will celebrate it on WTTW11, Websites WTTW Prime, and wttw.com. You’ll find highlights of this special programming wttw.com on page 7 and at wttw.com/blackhistorymonth. Don’t miss new Finding Your wfmt.com Roots specials, in which Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores race, family, and Publisher identity in today’s America by uncovering the genealogy of Michael Strahan, Anne Gleason S. Epatha Merkerson, and many more. -

![[Pdf] Noma: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine René Redzepi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8068/pdf-noma-time-and-place-in-nordic-cuisine-ren%C3%A9-redzepi-948068.webp)

[Pdf] Noma: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine René Redzepi

[Pdf] Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine René Redzepi - free pdf download Download Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine PDF, Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Download PDF, Read Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Full Collection René Redzepi, Read Online Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Ebook Popular, PDF Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Full Collection, free online Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine, online free Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine, online pdf Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine, pdf download Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine, by René Redzepi Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine, book pdf Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine, René Redzepi epub Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine, Read Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Book Free, Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Ebooks, Free Download Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Best Book, Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Read Download, Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Ebook Download, Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Book Download, PDF Download Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Free Collection, Free Download Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Books [E-BOOK] Noma: Time And Place In Nordic Cuisine Full eBook, CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD If you survived boys arthur milk or even writes this book for contemporary quiz as a companion book. The story is told from her perspective and i expected knowing what happened next and the second couple of around some day. -

The Best 25 the Best of the Best - 1995-2020 List of the Best for 25 Years in Each Category for Each Country

1995-2020 The Best 25 The Best of The Best - 1995-2020 List of the Best for 25 years in each category for each country It includes a selection of the Best from two previous anniversary events - 12 years at Frankfurt Old Opera House - 20 years at Frankfurt Book Fair Theater - 25 years will be celebrated in Paris June 3-7 and China November 1-4 ALL past Best in the World are welcome at our events. The list below is a shortlist with a limited selection of excellent books mostly still available. Some have updated new editions. There is only one book per country in each category Countries Total = 106 Algeria to Zimbabwe 96 UN members, 6 Regions, 4 International organizations = Total 106 TRENDS THE CONTINENTS SHIFT The Best in the World By continents 1995-2019 1995-2009 France ........................11% .............. 13% ........... -2 Other Europe ..............38% ............. 44% ..........- 6 China .........................8% ............... 3% .......... + 5 Other Asia Pacific .......20% ............. 15% ......... + 5 Latin America .............11% ............... 5% .......... + 6 Anglo America ..............9% ............... 18% ...........- 9 Africa .......................... 3 ...................2 ........... + 1 Total _______________ 100% _______100% ______ The shift 2009-2019 in the Best in the World is clear, from the West to the East, from the North to the South. It reflects the investments in quality for the new middle class that buys cookbooks. The middle class is stagnating at best in the West and North, while rising fast in the East and South. Today 85% of the world middleclass is in Asia. Do read Factfulness by Hans Rosling, “a hopeful book about the potential for human progress” says President Barack Obama. -

Stagier Introductory Note

Stagier Introductory Note Thank you for your application to stage at Restaurant noma. We appreciate that you have chosen this restaurant to further your professional development. This document is as a brief introduction to our philosophy and work ethics. At noma, we not only place an immense value on the products that we work with, but also on the people that work with us. Whilst here, you will have the opportunity to handle and prepare very rare and costly ingredients – from wild dandelions shoots foraged from around Copenhagen to hand-dived sea urchins flown in from Norway especially for us and still alive. However, we must always bear in mind that every product has more than simply monetary value; there are sentimental, humane and intrinsic costs associated with everything we receive from our suppliers. You might find the working system different to what you have experienced before. At noma, everyone is entitled to put forward their opinion – indeed, we encourage everyone to do so. Noma might be a restaurant that deals solely with Scandinavian and Nordic produce, but our staff are global; it is their ideas and input that have helped shape noma into what it is today. Therefore, if you have a suggestion or comment that you consider valuable, please share it – providing that the time and place are right, of course. The following guidelines will explain what is expected of you whilst part of our team. • The Neighbourhood Restaurant noma resides on the artificial island of Christianshavn in Copenhagen. Once a working-class area between the Inner City and Island of Amager, today it is a trendy part of the city with a unique identity. -

February 2012 AETN Magazine

Magazine February 2012 A Magazine for the Supporters of the AETN Foundation “Daisy Bates: First Lady of Little Rock” premieres on “Independent Lens” Thursday, Feb. 2, at 8 p.m., and repeats Sunday, Feb. 5, at 7 p.m. Arkansas Educational Television Network Contents “Exploring Arkansas”. 3 Letter from the director. 4 Lifelong ArkansanLifelong Remembers Arkansan AETN Foundation remembers in His Estate Plan AETN local productions . 6 The ArkansasAETN Educational Foundation Telecommunications in his Network estate (AETN) plan Foundation has AETN Foundation’s received a $237,988 gift from the estate of Norris Cunningham Taylor. Ambassadors Circle . 7 The Arkansas Educational Telecommu- television as a significant means of ac- PBS series highlights. 8-11 Thisnications gift will Network be added (AETN) to the Foundation AETN Foundation complishing endowment just that.” funds, which through continuedhas received growth a $237,988 will be gift able from to the provide additional support for the purchase and Primetime schedules. 12-21 estate of Norris Cunningham Taylor. The AETN Foundation exists to raise the creation of quality, educational programming seen on AETN throughout Arkansas. Community Cinema . 20-21 funds necessary to support AETN’s mis- Daytime on AETN-1 . 22-23 This gift will be added to the AETN sion of enhancing lives through trusted “WeFoundation are deeply endowment grateful funds,to Mr. which Taylor forpublic remembering television programsAETN in and th iseduca way- ,” Daytime on AETN-2 Create and AETN Foundation Executive Director Allen Weatherly said. “A gift of this size AETN-3 Plus . 24-27 through continued growth will be able tional services. -

New Nordic Cuisine Thesis Paolo T

Paolo Tamborini Master Thesis Master of Social Science in Management of Creative Business Processes (CBP) Copenhagen Business School August 2013 The Transposition of Culinary Models New Nordic Cuisine in Italy Academic advisor: Jesper Strandgaard Pedersen Department of Organization Page count: 62 st. pages Characters count (incl. spaces): 98.748 Abstract In the last years New Nordic Cuisine has gained international recognition, while it remained confined within the boundaries of Nordic countries. This project deals with the transposition of New Nordic Cuisine in Italy, maintaining an entrepreneurial approach in the view of a potential opening of the first New Nordic Cuisine restaurant in Italy. Starting from a framing of the culinary and gastronomic industry within the sector of the Creative industries, literature from the fields of National cultures, organizational translation and legitimization and identity is reviewed, in order to give this study a solid theoretical foundation. Through the elaboration of cross-cultural studies from the perspective of Denmark and Italy, insights into the two national cultures are gained, useful for drawing practical managerial considerations. This study has a qualitative nature. The sources of empirical data are interviews and a survey. In one case also a field visit was performed. The interviews were performed with a semi-structured approach following the guidelines of the qualitative interview. The survey does not follow a quantitative approach. Through the interviews and analysis of cases, emerged the importance of maintaining a clear Nordic identity for New Nordic Cuisine in Italy. At the same time the Italian public thinks that an integration with Italian elements is needed in order to transpose successfully the Nordic cuisine. -

Oslo a Monocle City Survey — from Forest to Fjord: the Best That Norway’S Dynamic Capital Has to Offer—

OSLO A MONOCLE CITY SURVEY — From forest to fjord: the best that Norway’s dynamic capital has to offer — 01 02 03 04 05 06 City on Business Capital Better Great Recipes for the move with pleasure of culture by design outdoors success The political The best Oslo Tour the city’s Oslo’s aspiring We head Dining options movers and entrepreneurs, arts scene creative talents beyond the that reserve shakers get- from small via festivals, and the archi- city limits for Oslo’s place ting creative independents theatre, music tects building a natural at the top culi- at City Hall. to oil giants. and more. a bright future. wander. nary table. OSLO IS AT THE HEART of Norway´s business and cultural life. As the capital city of Norway it powers the cultural and business environments that have created much of the Norwegian society we know today. BY BEING A SMALL BIG CITY, it has nourished collaboration across business sectors and social struc- tures and become a city of talents. Oslo is a melting pot for creativity, knowledge and capital. ROOTED IN THE OPEN, transparent and trustworthy Norwegian society, Oslo is now a leading region of international business and entrepre- neurship. WELCOME TO OSLO - THE CAPITAL OF NORWAY. Photo: Damian Heinisch Photo: ���� �������� ������ ������ ��� ������������ �� ��� ���� ���� ������ ��� ��� ���� ���� ������ ���. OSL - Oslo Airport, Statoil ASA, ØYA - Music festival, NFI -Film Commision Norway, Aspelin Ramm Eiendom AS, Tjuvholmen KS, T - Norwegian Trekking Association, Visit Oslo and the City of Oslo. Poll to poll WELCOME & CONTENTS Norway has topped the Legatum Institute’s annual Prosperity Index for the past four years and last year saw Norway rise five places to a lofty sixth position in the Entrepreneurship and Opportunity Index. -

GOURMAND MAGAZINE the International Cookbook Revue Issue 13 / August 2011

GOURMAND MAGAZINE The International Cookbook Revue Issue 13 / August 2011 Remarquable female cookbook authors The New Women Power PLUS: Paris Cookbook Fair 2012 Meet the Best Chinese Chefs Africa: Discover a Culinary Giant GOURMAND MAGAZINE Issue 13 / August 2011 index Paris Cookbook Fair 2012 3 Meet the Best Chinese Chefs 4 Back for Good - Sara La Fountain 5 8 Rose Elliot: Queen of Vegetarian Cooking 6 Suzanne Husseini Builds Bridges 7 The Gourmand Award Effect 8 Uncover the African Treasure 10 “The Paris Boulevard“ by Carl Warner 14 14 News from the Gourmand family 16 Become part of To watch the our facebook Gourmand Magazine is video, click on community and the picture! get all information a crossmedia product. by ticking on the Whenever you see this sym- facebook logo. bol, you can see a video with additional information. INTERACTIVE GOURMAND PARIS COOKBOOK FAIR COVER WWW.COOKBOOKFAIR.COM IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN MAGAZINE BY CARL WARNER PICTURES OF THE AWARDS EDITORIAL OFFICE: OR THE COOKBOOK FAIR PUBLISHER: ADRESS OF MEDIA OWNER AND GOURMAND MAGAZINE PLEASE CONTACT EDOUARD COINTREAU PUBLISHER: OLAF PLOTKE TIBOR BÁRÁNY: EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: GOURMAND INTERNATIONAL LOHBERG 37 WWW.TIBORFOTO.COM OLAF PLOTKE (V.I.S.D.P.) MARQUÉS DE URQUIJO, 47589 UEDEM, GERMANY [email protected] HOTOS 6-BAJO A., [email protected] P : +46 705 98 24 88 TIBOR BÁRÁNY, OLAF PLOTKE MADRID, 28008, SPAIN WWW.GOURMAND-MAGAZINE.COM page 2 Issue 13 / August 2011 GOURMAND MAGAZINE Issue 13 / August 2011 Picture: Carl Warner Welcome to the Capital of Taste The Paris Cookbook Fair 2012, March 7-11 The Paris Cookbook offer a breathtaking One of the oldest 150 countries for cook- Fair begins to take sha- look inside the long drinks in the world is books and 64 countries pe. -

POSTEN Velkommen

The POSTEN June/July/August 2020 Established 1984 Co-President’s Column Inside this Issue “If I ever get some free time, I’ll 2 Co-President’s Column finally...”, is a phrase I’ve used (cont’d) too often in the past; and now it seems to have caught up with all 3 Desert Fjord Library of us. What have you been doing News during your “free time” as you’ve withdrawn to the safety of your 4 Summer Birthdays; home and had your schedule Membership Matters changed by cancellations and long -term delays? 5 New Scandinavian Before the virus I had a good Cooking number of days and hours set 6 Scandinavian Cooking aside for Sons of Norway activi- ties. It was a difficult decision to (cont’d); Friluftsliv cancel the Scandinavian Viking 7 Scholarships from Sons Festival at the end of March, but of Norway Foundation in retrospect, by not gathering hundreds of people (most over the 8 Desert Fjord Information age of 60) in packed rooms, we may have saved lives. The District 6 Convention, scheduled to be held in Mesa in June, has been postponed until 2022. Desert Fjord Lodge decided to cancel the April meeting, the Syttende Mai picnic, and all other events until this Fall. Our lodge leadership will be meeting over the summer to determine when and how we may safely resume meetings. I certainly miss seeing each of you, enjoy- ing fellowship, sharing a meal and learning more about my heritage. Despite having all of this new-found “free time”, I still find my- self lacking time to do everything on my wish list.