Protected Areas by Management 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Declaración De Impacto Ambiental Estratégica

Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales DECLARACIÓN DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL ESTRATÉGICA ESTUDIO DEL CARSO Septiembre 2009 Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales DECLARACIÓN DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL ESTRATÉGICA ESTUDIO DEL CARSO Septiembre 2009 HOJA PREÁMBULO DIA- Núm: JCA-__-____(PR) Agencia: Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales Título de la acción propuesta: Adopción del Estudio del Carso Funcionario responsable: Daniel J. Galán Kercadó Secretario Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales PO Box 366147 San Juan, PR 00936-6147 787 999-2200 Acción: Declaración de Impacto Ambiental – Estratégica Estudio del Carso Resumen: La acción propuesta consiste en la adopción del Estudio del Carso. En este documento se presenta el marco legal que nos lleva a la preparación de este estudio científico y se describen las características geológicas, hidrológicas, ecológicas, paisajísticas, recreativas y culturales que permitieron la delimitación de un área que abarca unas 219,804 cuerdas y que permitirá conservar una adecuada representación de los elementos irremplazables presente en el complejo ecosistema conocido como carso. Asimismo, se evalúa su estrecha relación con las políticas públicas asociadas a los usos de los terrenos y como se implantarán los hallazgos mediante la enmienda de los reglamentos y planes aplicables. Fecha: Septiembre de 2009 i TABLA DE CONTENIDO Capítulo I000Descripción del Estudio del Carso .................................................1 -

Reporton the Rare Plants of Puerto Rico

REPORTON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO tii:>. CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION ~ Missouri Botanical Garden St. Louis, Missouri July 15, l' 992 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Center for Plant Conservation would like to acknowledge the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the W. Alton Jones Foundation for their generous support of the Center's work in the priority region of Puerto Rico. We would also like to thank all the participants in the task force meetings, without whose information this report would not be possible. Cover: Zanthoxy7um thomasianum is known from several sites in Puerto Rico and the U.S . Virgin Islands. It is a small shrub (2-3 meters) that grows on the banks of cliffs. Threats to this taxon include development, seed consumption by insects, and road erosion. The seeds are difficult to germinate, but Fairchild Tropical Garden in Miami has plants growing as part of the Center for Plant Conservation's .National Collection of Endangered Plants. (Drawing taken from USFWS 1987 Draft Recovery Plan.) REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements A. Summary 8. All Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands Species of Conservation Concern Explanation of Attached Lists C. Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] species D. Blank Taxon Questionnaire E. Data Sources for Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [B] species F. Pue~to Rico\Virgin Islands Task Force Invitees G. Reviewers of Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] Species REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO SUMMARY The Center for Plant Conservation (Center) has held two meetings of the Puerto Rlco\Virgin Islands Task Force in Puerto Rico. -

Sitios Arqueológicos De Ponce

Sitios Arqueológicos de Ponce RESUMEN ARQUEOLÓGICO DEL MUNICIPIO DE PONCE La Perla del Sur o Ciudad Señorial, como popularmente se le conoce a Ponce, tiene un área de aproximadamente 115 kilómetros cuadrados. Colinda por el oeste con Peñuelas, por el este con Juana Díaz, al noroeste con Adjuntas y Utuado, y al norte con Jayuya. Pertenece al Llano Costanero del Sur y su norte a la Cordillera Central. Ponce cuenta con treinta y un barrios, de los cuales doce componen su zona urbana: Canas Urbano, Machuelo Abajo, Magueyes Urbano, Playa, Portugués Urbano, San Antón, Primero, Segundo, Tercero, Cuarto, Quinto y Sexto, estos últimos seis barrios son parte del casco histórico de Ponce. Por esta zona urbana corren los ríos Bucaná, Portugués, Canas, Pastillo y Matilde. En su zona rural, los barrios que la componen son: Anón, Bucaná, Canas, Capitanejo, Cerrillos, Coto Laurel, Guaraguao, Machuelo Arriba, Magueyes, Maragüez, Marueño, Monte Llanos, Portugués, Quebrada Limón, Real, Sabanetas, San Patricio, Tibes y Vallas. Ponce cuenta con un rico ajuar arquitectónico, que se debe en parte al asentamiento de extranjeros en la época en que se formaba la ciudad y la influencia que aportaron a la construcción de las estructuras del casco urbano. Su arquitectura junto con los yacimientos arqueológicos que se han descubierto en el municipio, son parte del Inventario de Recursos Culturales de Ponce. Esta arquitectura se puede apreciar en las casas que fueron parte de personajes importantes de la historia de Ponce como la Casa Paoli (PO-180), Casa Salazar (PO-182) y Casa Rosaly (PO-183), entre otras. Se puede ver también en las escuelas construidas a principios del siglo XX: Ponce High School (PO-128), Escuela McKinley (PO-131), José Celso Barbosa (PO-129) y la escuela Federico Degetau (PO-130), en sus iglesias, la Iglesia Metodista Unida (PO-126) y la Catedral Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (PO-127) construida en el siglo XIX. -

Two New Scorpions from the Puerto Rican Island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae)

Two new scorpions from the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Rolando Teruel, Mel J. Rivera & Carlos J. Santos September 2015 — No. 208 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Volume 52: 1-415 Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands Editors Pedro Acevedo-Rodríguez and Mark T. Strong Department of Botany National Museum of Natural History Washington, DC 2005 ABSTRACT Acevedo-Rodríguez, Pedro and Mark T. Strong. Monocots and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, volume 52: 415 pages (including 65 figures). The present treatment constitutes an updated revision for the monocotyledon and gymnosperm flora (excluding Orchidaceae and Poaceae) for the biogeographical region of Puerto Rico (including all islets and islands) and the Virgin Islands. With this contribution, we fill the last major gap in the flora of this region, since the dicotyledons have been previously revised. This volume recognizes 33 families, 118 genera, and 349 species of Monocots (excluding the Orchidaceae and Poaceae) and three families, three genera, and six species of gymnosperms. The Poaceae with an estimated 89 genera and 265 species, will be published in a separate volume at a later date. When Ackerman’s (1995) treatment of orchids (65 genera and 145 species) and the Poaceae are added to our account of monocots, the new total rises to 35 families, 272 genera and 759 species. The differences in number from Britton’s and Wilson’s (1926) treatment is attributed to changes in families, generic and species concepts, recent introductions, naturalization of introduced species and cultivars, exclusion of cultivated plants, misdeterminations, and discoveries of new taxa or new distributional records during the last seven decades. -

Puerto Rico: Nature and Birding January 3-11, 2013

PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 Phone 520.558.1146 Toll free 866.900.1146 Fax 650.471.7667 Email [email protected] Puerto Rico: Nature and Birding January 3-11, 2013 “Peg Abbott is a pro...full of knowledge and diplomacy. She is generous with her time and attention to our questions.” - Rolla Wagner Join us this January to explore, among varied island habitats, the only tropical forest in America’s National Forest system – in Puerto Rico! The 28,000 acre-El Yunque National Forest is located in the rugged Sierra de Luquillo Mountains, just 25 miles east-southeast of San Juan. In addition to this lush, exciting gem of the US National Forest system, we visit Laguna Cartagena National Wildlife Refuge and several state forest and private reserves. Puerto Rico has over 260 species of birds, more than a dozen of which occur nowhere else. With an excellent road system and an accomplished local guide, we have a great chance to see a good portion of the island’s 17* endemics, and a good number of the twenty-or-so additional Caribbean regional specialties. We visit several Important Bird Areas designated by Birdlife International. There is a good field guide for the island, written by Herbert Raffaele, the Birds of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. A nice addition is the newer, Puerto Rico´s Birds in Photograph by Mark Oberle, which includes a CD with the bird sounds. We’ll also focus on the island’s lush (east side) and arid (southwest corner, due to a mountain rain shadow effect) flora. -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY of the PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. July 1981 VIRGIN ISLANDS CULEBRA PUERTO RlCO Fig. 1. Map of the Puerto Rican Island Shelf. Rectangles A - E indicate boundaries of maps presented in more detail in Appendix I. 1. Cayo Santiago, 2. Cayo Batata, 3. Cayo de Afuera, 4. Cayo de Tierra, 5. Cardona Key, 6. Protestant Key, 7. Green Key (st. ~roix), 8. Caiia Azul ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 251 ERRATUM The following caption should be inserted for figure 7: Fig. 7. Temperature in and near a small clump of vegetation on Cayo Ahogado. Dots: 5 cm deep in soil under clump. Circles: 1 cm deep in soil under clump. Triangles: Soil surface under clump. Squares: Surface of vegetation. X's: Air at center of clump. Broken line indicates intervals of more than one hour between measurements. BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwolel, Richard Levins2 and Michael D. Byer3 INTRODUCTION There has been a recent surge of interest in the biogeography of archipelagoes owing to a reinterpretation of classical concepts of evolution of insular populations, factors controlling numbers of species on islands, and the dynamics of inter-island dispersal. The literature on these subjects is rapidly accumulating; general reviews are presented by Mayr (1963) , and Baker and Stebbins (1965) . Carlquist (1965, 1974), Preston (1962 a, b), ~ac~rthurand Wilson (1963, 1967) , MacArthur et al. (1973) , Hamilton and Rubinoff (1963, 1967), Hamilton et al. (1963) , Crowell (19641, Johnson (1975) , Whitehead and Jones (1969), Simberloff (1969, 19701, Simberloff and Wilson (1969), Wilson and Taylor (19671, Carson (1970), Heatwole and Levins (1973) , Abbott (1974) , Johnson and Raven (1973) and Lynch and Johnson (1974), have provided major impetuses through theoretical and/ or general papers on numbers of species on islands and the dynamics of insular biogeography and evolution. -

Us Caribbean Regional Coral Reef Fisheries Management Workshop

Caribbean Regional Workshop on Coral Reef Fisheries Management: Collaboration on Successful Management, Enforcement and Education Methods st September 30 - October 1 , 2002 Caribe Hilton Hotel San Juan, Puerto Rico Workshop Objective: The regional workshop allowed island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to identify successful coral reef fishery management approaches. The workshop provided the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force with recommendations by local, regional and national stakeholders, to develop more effective and appropriate regional planning for coral reef fisheries conservation and sustainable use. The recommended priorities will assist Federal agencies to provide more directed grant and technical assistance to the U.S. Caribbean. Background: Coral reefs and associated habitats provide important commercial, recreational and subsistence fishery resources in the United States and around the world. Fishing also plays a central social and cultural role in many island communities. However, these fishery resources and the ecosystems that support them are under increasing threat from overfishing, recreational use, and developmental impacts. This workshop, held in conjunction with the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force Meeting, brought together island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel to compare methods that have been successful, including regulations that have worked, effective enforcement, and education to reach people who can really effect change. These efforts were supported by Federal fishery managers and scientists, Puerto Rico Sea Grant, and drew on the experience of researchers working in the islands and Florida. The workshop helped develop approaches for effective fishery management strategies in the U.S. Caribbean and recommended priority actions to the U.S. -

Protected Areas by Management 9

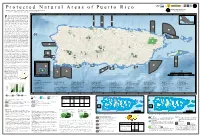

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Bookletchart™ Bahía De Ponce and Approaches NOAA Chart 25683 a Reduced-Scale NOAA Nautical Chart for Small Boaters

BookletChart™ Bahía de Ponce and Approaches NOAA Chart 25683 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the Channels.–The principal entrance is E of Isla de Cardona. A Federal project provides for a 600-foot-wide entrance channel 36 feet deep, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration then an inner channel 200-foot-wide 36 feet deep leading to an irregular National Ocean Service shaped turning basin, with a 950-foot turning diameter adjacent to the Office of Coast Survey municipal bulkhead. The entrance channel is marked by a 015° lighted range, lights, and www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov buoys; do not confuse the rear range light with the flashing red radio 888-990-NOAA tower lights back of it. A 0.2-mile-wide channel between Isla de Cardona and Las Hojitas is sometimes used by small vessels with local knowledge. What are Nautical Charts? Anchorages.–The usual anchorage is NE of Isla de Cardona in depths of 30 to 50 feet, although vessels can anchor in 30 to 40 feet NW of Las Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show Hojitas. A small-craft anchorage is NE of Las Hojitas in depths of 18 to 28 water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much feet. (See 110.1 and 110.255, chapter 2, for limits and regulations.) A more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and well-protected anchorage for small boats in depths of 19 to 30 feet is NE efficient navigation. -

Puerto Rico Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy 2005

Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico PUERTO RICO COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION STRATEGY 2005 Miguel A. García José A. Cruz-Burgos Eduardo Ventosa-Febles Ricardo López-Ortiz ii Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Financial support for the completion of this initiative was provided to the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Federal Assistance Office. Special thanks to Mr. Michael L. Piccirilli, Ms. Nicole Jiménez-Cooper, Ms. Emily Jo Williams, and Ms. Christine Willis from the USFWS, Region 4, for their support through the preparation of this document. Thanks to the colleagues that participated in the Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) Steering Committee: Mr. Ramón F. Martínez, Mr. José Berríos, Mrs. Aida Rosario, Mr. José Chabert, and Dr. Craig Lilyestrom for their collaboration in different aspects of this strategy. Other colleagues from DNER also contributed significantly to complete this document within the limited time schedule: Ms. María Camacho, Mr. Ramón L. Rivera, Ms. Griselle Rodríguez Ferrer, Mr. Alberto Puente, Mr. José Sustache, Ms. María M. Santiago, Mrs. María de Lourdes Olmeda, Mr. Gustavo Olivieri, Mrs. Vanessa Gautier, Ms. Hana Y. López-Torres, Mrs. Carmen Cardona, and Mr. Iván Llerandi-Román. Also, special thanks to Mr. Juan Luis Martínez from the University of Puerto Rico, for designing the cover of this document. A number of collaborators participated in earlier revisions of this CWCS: Mr. Fernando Nuñez-García, Mr. José Berríos, Dr. Craig Lilyestrom, Mr. Miguel Figuerola and Mr. Leopoldo Miranda. A special recognition goes to the authors and collaborators of the supporting documents, particularly, Regulation No. -

To See Our Puerto Rico Vacation Planning

DISCOVER PUERTO RICO LEISURE + TRAVEL 2021 Puerto Rico Vacation Planning Guide 1 IT’S TIME TO PLAN FOR PUERTO RICO! It’s time for deep breaths and even deeper dives. For simple pleasures, dramatic sunsets and numerous ways to surround yourself with nature. It’s time for warm welcomes and ice-cold piña coladas. As a U.S. territory, Puerto Rico offers the allure of an exotic locale with a rich, vibrant culture and unparalleled natural offerings, without needing a passport or currency exchange. Accessibility to the Island has never been easier, with direct flights from domestic locations like New York, Charlotte, Dallas, and Atlanta, to name a few. Lodging options range from luxurious beachfront resorts to magical historic inns, and everything in between. High standards of health and safety have been implemented throughout the Island, including local measures developed by the Puerto Rico Tourism Company (PRTC), alongside U.S. Travel Association (USTA) guidelines. Outdoor adventures will continue to be an attractive alternative for visitors looking to travel safely. Home to one of the world’s largest dry forests, the only tropical rainforest in the U.S. National Forest System, hundreds of underground caves, 18 golf courses and so much more, Puerto Rico delivers profound outdoor experiences, like kayaking the iridescent Bioluminescent Bay or zip lining through a canopy of emerald green to the sound of native coquí tree frogs. The culture is equally impressive, steeped in European architecture, eclectic flavors of Spanish, Taino and African origins and a rich history – and welcomes visitors with genuine, warm Island hospitality. Explore the authentic local cuisine, the beat of captivating music and dance, and the bustling nightlife, which blended together, create a unique energy you won’t find anywhere else.