Rotuman Life Experiences 1890–1960 Compiled and Edited by Alan Howard and Jan Rensel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lx1/Rtetcanjviuseum

lx1/rtetcanJViuseum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 1707 FEBRUARY 1 9, 1955 Notes on the Birds of Northern Melanesia. 31 Passeres BY ERNST MAYR The present paper continues the revisions of birds from northern Melanesia and is devoted to the Order Passeres. The literature on the birds of this area is excessively scattered, and one of the functions of this review paper is to provide bibliographic references to recent litera- ture of the various species, in order to make it more readily available to new students. Another object of this paper, as of the previous install- ments of this series, is to indicate intraspecific trends of geographic varia- tion in the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon Islands and to state for each species from where it colonized northern Melanesia. Such in- formation is recorded in preparation of an eventual zoogeographic and evolutionary analysis of the bird fauna of the area. For those who are interested in specific islands, the following re- gional bibliography (covering only the more recent literature) may be of interest: BISMARCK ARCHIPELAGO Reichenow, 1899, Mitt. Zool. Mus. Berlin, vol. 1, pp. 1-106; Meyer, 1936, Die Vogel des Bismarckarchipel, Vunapope, New Britain, 55 pp. ADMIRALTY ISLANDS: Rothschild and Hartert, 1914, Novitates Zool., vol. 21, pp. 281-298; Ripley, 1947, Jour. Washington Acad. Sci., vol. 37, pp. 98-102. ST. MATTHIAS: Hartert, 1924, Novitates Zool., vol. 31, pp. 261-278. RoOK ISLAND: Rothschild and Hartert, 1914, Novitates Zool., vol. 21, pp. 207- 218. -

Echoes of Pacific War

ECHOES of Pacific War Edited by Deryck Scarr, Niel Gunson, Jennifer Terrell Echoes of Pacific War Edited by Deryck Scarr, Niel Gunson, Jennifer Terrell Papers from the 7th Tongan History Conference held in Canberra in January 1997 TARGET OCEANIA CANBERRA 1998 © Deryck Scarr, Niel Gunson, Jennifer Terrell 1998 This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Book and cover design by Jennifer Terrell Printed by ANU Printing and Publishing Service ISBN 0-646-36000-0 Published by TARGET OCEANIA c/ o Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia Contents Maps and Figures v Fo reword ix Introduction xiii 1 Behind the battle lines: Tonga in World War II EUZABETHWOOD-EILEM 1 2 Changing values and changed psychology of Tongans during and since World War II 'I. F. HELU 26 3 Airplanes and saxaphones: post-war images in the visual and peiforming arts ADRIENNE L. KAEPPIER 38 4 Tonga and Australia since Wo rld War II GARETH GRAINGER 64 5 New behaviours and migration since Wo rld War II SIOSIUA F. POUVALU LAFITANI 76 6 The churches in Tonga since World War II JOHN GARRE'IT 87 7 Introduction and development of fa mily planning in Tonga 1958-1990 HENRY IVARATURE 99 8 Analysing the emergent mi ddle class - the 1990s KERRY JAMES 110 9 Changing interpretations of the kava ritual MEREDITH FILIHIA 127 10 How To ngan is a Tongan? Cultural authenticity revisited HELEN MORTON 149 Bibliograp hy 167 Index 173 Contributors 182 Maps Map 1: TheTonga Islands vii Map 2: Tongatapu 5 Map 3: Nuku'alofa 10 Figures Figure 1. -

Rotuman Educational Resource

Fäeag Rotuam Rotuman Language Educational Resource THE LORD'S PRAYER Ro’ạit Ne ‘Os Gagaja, Jisu Karisto ‘Otomis Ö’fāat täe ‘e lạgi, ‘Ou asa la ȧf‘ȧk la ma’ma’, ‘Ou Pure'aga la leum, ‘Ou rere la sok, fak ma ‘e lạgi, la tape’ ma ‘e rȧn te’. ‘Äe la nāam se ‘ạmisa, ‘e terạnit 'e ‘i, ta ‘etemis tē la ‘ā la tạu mar ma ‘Äe la fạu‘ạkia te’ ne ‘otomis sara, la fak ma ne ‘ạmis tape’ ma rē vạhia se iris ne sar ‘e ‘ạmisag. ma ‘Äe se hoa’ ‘ạmis se faksara; ‘Äe la sại‘ạkia ‘ạmis ‘e raksa’a, ko pure'aga, ma ne’ne’i, ma kolori, mou ma ke se ‘äeag, se av se ‘es gata’ag ne tore ‘Emen Rotuman Language 2 Educational Resource TABLE OF CONTENTS ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY 4 ROGROG NE ROTUMA 'E 'ON TẠŪSA – Our history 4 'ON FUẠG NE AS TA ROTUMA – Meaning behind Rotuma 5 HẠITOHIẠG NE FUẠG FAK PUER NE HANUA – Chiefly system 6 HATAG NE FĀMORI – Population 7 ROTU – Religion 8 AGA MA GARUE'E ROTUMA – Lifestyle on the island 8 MAK A’PUMUẠ’ẠKI(T) – A treasured song 9 FŪ’ÅK NE HANUA GEOGRAPHY 10 ROTUMA 'E JAJ(A) NE FITI – Rotuma on the map of Fiji 10 JAJ(A) NE ITU ’ HIFU – Map of the seven districts 11 FÄEAG ROTUẠM TA LANGUAGE 12 'OU ‘EA’EA NE FÄEGA – Pronunciation Guide 12-13 'ON JĪPEAR NE FÄEGA – Notes on Spelling 14 MAF NE PUKU – The Rotuman Alphabet 14 MAF NE FIKA – Numbers 15 FÄEAG ‘ES’ AO - Useful words 16-18 'OU FÄEAG’ÅK NE 'ÄE – Introductions 19 UT NE FAMORI A'MOU LA' SIN – Commonly Frequented Places 20 HUẠL NE FḀU TA – Months of the year 21 AG FAK ROTUMA CULTURE 22 KATO’ AGA - Traditional ceremonies 22-23 MAMASA - Welcome Visitors and returnees 24 GARUE NE SI'U - Artefacts 25 TĒFUI – Traditional garland 26-28 MAKA - Dance 29 TĒLA'Ā - Food 30 HANUJU - Storytelling 31-32 3 ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY Legend has it that Rotuma’s first inhabitants Consequently, the two religious groups originated from Samoa led by Raho, a chief, competed against each other in the efforts to followed by the arrival of Tongan settlers. -

Hoʻoulu Laka Hula & Chant Protocol Training Packet

Ho‘oulu Laka Hula and Protocol Training Packet Lālākea Foundation Ka ‘Aha Hula ‘O Hālauaola June 14-23, 2018 Hilo, Hawaiʻi O Ku, O Ka O Wahineomao (Chapter 6) E Nihi Ka Hele I Ka Uka O Puna Emerson, 2005 1. E nihi ka hele i ka uka o Puna 2. Mai ako i ka pua 3. O lilo i ke ala o ka hewahewa 4. Ua huna ia ke kino i ka pohaku 5. O ka pua nae ke ahu nei i ke alanui 6. Alanui hele o ka unu kupukupu e 7. Ka ulia 8. A kaunu no anei oe o ke aloha la 9. Hele ae a komo i ka hale o Pele 10. Ua huahuai Kahiki lapa uila 11. Pele e, huaina hoi A Loko Au O Panaewa Alala ka pua, oli o Hiiaka Kapihenui, 16 January 1862 Bush & Paaluhi, 17 February 1893. *Emerson. *Halawai me ka pua 1. A loko au o Panaewa 2. Halawai me ka puaa a ka wahine 3. Me kuu maka lehua i uka 4. Me ka malu koi i ka nahele 5. E ue ana i ka laau 6. Alala ka puaa a ka wahine 7. He puaa kanaenae 8. He kanaenae mohai ola 9. E ola ia Pele 10. I ka wahine o ka lua e 2 The answer to this appeal for admission was in these words: Mele Komo E hea i ke kanaka e komo maloko, E hanai ai a hewa waha; Eia no ka uku la, o ka leo, A he leo wale no, e! (Translation) Welcoming-Song Call to the man to come in, And eat till the mouth is estopt; And this the reward, the voice, Simply the voice. -

Survival Guide on the Road

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd PAGE ON THE YOUR COMPLETE DESTINATION GUIDE 42 In-depth reviews, detailed listings ROAD and insider tips Vanua Levu & Taveuni p150 The Mamanuca & Yasawa Groups p112 Ovalau & the Lomaiviti Group Nadi, Suva & Viti Levu p137 p44 Kadavu, Lau & Moala Groups p181 PAGE SURVIVAL VITAL PRACTICAL INFORMATION TO 223 GUIDE HELP YOU HAVE A SMOOTH TRIP Directory A–Z .................. 224 Transport ......................... 232 Directory Language ......................... 240 student-travel agencies A–Z discounts on internatio airfares to full-time stu who have an Internatio Post offices 8am to 4pm Student Identity Card ( Accommodation Monday to Friday and 8am Application forms are a Index ................................ 256 to 11.30am Saturday Five-star hotels, B&Bs, able at these travel age Restaurants lunch 11am to hostels, motels, resorts, tree- Student discounts are 2pm, dinner 6pm to 9pm houses, bungalows on the sionally given for entr or 10pm beach, campgrounds and vil- restaurants and acco lage homestays – there’s no Shops 9am to 5pm Monday dation in Fiji. You ca Map Legend ..................... 263 to Friday and 9am to 1pm the student health shortage of accommodation ptions in Fiji. See the ‘Which Saturday the University of nd?’ chapter, p 25 , for PaciÀ c (USP) in ng tips and a run-down hese options. Customs Regulations E l e c t r Visitors can leave Fiji without THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Dean Starnes, Celeste Brash, Virginia Jealous “All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over. So go!” TONY WHEELER, COFOUNDER – LONELY PLANET Get the right guides for your trip PAGE PLAN YOUR PLANNING TOOL KIT 2 Photos, itineraries, lists and suggestions YOUR TRIP to help you put together your perfect trip Welcome to Fiji ............... -

Rotuma: Interpreting a Wedding

ROTUMA: INTERPRETING A WEDDING Alan Howard and Jan Rensei n most societies there are one or two activities that express, in highly condensed ways, what life is all about for its members. IIn Bali it is the cockfight,1 among the Australian Aborigines the corroboree, in Brazil there is carnival. One might make a case for the Super Bowl in the United States. On Rotuma, a small iso lated island in the South Pacific, weddings express, in practice and symbolically, the deepest values of the culture. In the bring ing together of a young man and young woman, in the work that goes into preparing the wedding feast, in the participation of chiefs both as paragons of virtue and targets of humor, in the dis plays of food and fine white mats, and in the sequence of ceremo nial rites performed, Rotumans communicate to one another what they care about most: kinship and community, fertility of the peo ple and land, the political balance between chiefs and common ers, and perpetuation of Rotuman custom. After providing a brief description of Rotuma and its people, we narrate an account of a wedding in which we participated. We then interpret key features of the wedding, showing how they express, in various ways, core Rotuman values. THE ISLAND AND ITS PEOPLE Rotuma is situated approximately three hundred miles north of Fiji, on the western fringe of Polynesia. The island is volcanic in origin, forming a land area of about seventeen square miles, with the highest craters rising to eight hundred feet above sea level. -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions

December 2019 Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions Lauren Dickey, Erica Downs, Andrew Taffer, and Heidi Holz with Drew Thompson, S. Bilal Hyder, Ryan Loomis, and Anthony Miller Maps and graphics created by Sue N. Mercer, Sharay Bennett, and Michele Deisbeck Approved for Public Release: distribution unlimited. IRM-2019-U-019755-Final Abstract This report provides a general map of the information environment of the Pacific Island Countries (PICs). The focus of the report is on the information environment—that is, the aggregate of individuals, organizations, and systems that shape public opinion through the dissemination of news and information—in the PICs. In this report, we provide a current understanding of how these countries and their respective populaces consume information. We map the general characteristics of the information environment in the region, highlighting trends that make the dissemination and consumption of information in the PICs particularly dynamic. We identify three factors that contribute to the dynamism of the regional information environment: disruptors, deficits, and domestic decisions. Collectively, these factors also create new opportunities for foreign actors to influence or shape the domestic information space in the PICs. This report concludes with recommendations for traditional partners and the PICs to support the positive evolution of the information environment. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor or client. Distribution Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. 12/10/2019 Cooperative Agreement/Grant Award Number: SGECPD18CA0027. This project has been supported by funding from the U.S. -

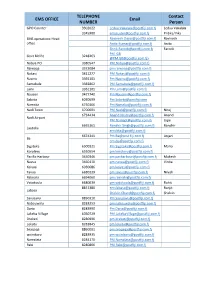

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Fara Way Rotuma

from Stories of the Southern Sea, by Lawrence Winkler Published as a Kindle book on December 26, 2013 Fara Way Rotuma “Their bodies were curiously marked with the figures of men, dogs, fishes and birds upon every part of them; so that every man was a moving landscape.” George Hamilton, Pandora’s surgeon, 1791 The whole scene was a moving landscape, directly under us, just over two hundred years after Captain Edwards had arrived on the HMS Pandora. He had been looking for the Bounty. We would find another. The pilot of our Britten-Norman banked off the huge cloud he had found over six hundred kilometers north of the rest of Fiji, and sliced down into it sideways, like he was cutting a grey soufflé. Nothing could have prepared us for the magnificence that opened up below, with the dispersal of the last gasping mists. A fringing reef, barely holding back the eternal explosions of rabid frothing foam and every blue in the reflected cosmos, encircled every green in nature. On the edge of both creations were the most spectacular beaches in the Southern Sea. Captain Edwards had called it Grenville Island. Two hundred years earlier, it was named Tuamoco by de Quiros, before he went on to establish his doomed New Jerusalem in Vanuatu. But that was less important for the moment. We had reestablished level flight, and were lining up on the dumbbell- shaped island’s only rectangular open space, a long undulating patch of grass, between the mountains and the ocean. Hardly more than a lawn bowling pitch anywhere else, here it was the airstrip, beside which a tiny remote paradise was waving all its arms. -

Fiji Meteorological Service Government of Republic of Fiji

FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICE GOVERNMENT OF REPUBLIC OF FIJI MEDIA RELEASE No. 13 1pm, Wednesday, 16 December, 2020 SEVERE TC YASA INTENSIFIES FURTHER INTO A CATEGORY 5 SYSTEM AND SLOW MOVING TOWARDS FIJI Warnings A Tropical Cyclone Warning is now in force for Yasawa and Mamanuca Group, Viti Levu, Vanua Levu and nearby smaller islands and expected to be in force for the rest of the group later today. A Tropical Cyclone Alert remains in force for the rest Fiji A Strong Wind Warning remains in force for the rest of Fiji. A Storm Surge and Damaging Heavy Swell Warning is now in force for coastal waters of Rotuma, Yasawa and Mamanuca Group, Viti Levu, Vanua Levu and nearby smaller islands. A Heavy Rain Warning remains in force for the whole of Fiji. A Flash Flood Alert is now in force for all low lying areas and areas adjacent to small streams along Komave to Navua Town, Navua Town to Rewa, Rewa to Korovou and Korovou to Rakiraki in Vanua Levu and is also in force for all low lying areas and areas adjacent to small streams of Vanua Levu along Bua to Dreketi, Dreketi to Labasa and along Labasa to Udu Point. Situation Severe tropical cyclone Yasa has rapidly intensified and upgraded further into a category 5 system at 3am today. Severe TC Yasa was located near 14.6 south latitude and 174.1 east longitude or about 440km west-northwest of Yasawa-i-Rara, about 500km northwest of Nadi and about 395km southwest of Rotuma at midday today. The system is currently moving eastwards at about 6 knots or 11 kilometers per hour.