Leendert Weeda Horace's Sermones Book 1 Credentials for Maecenas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17Th-First Half of the 18Th Century

The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Siedina, Giovanna. 2014. The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13065007 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2014 Giovanna Siedina All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Author: Professor George G. Grabowicz Giovanna Siedina The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century Abstract For the first time, the reception of the poetic legacy of the Latin poet Horace (65 B.C.-8 B.C.) in the poetics courses taught at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy (17th-first half of the 18th century) has become the subject of a wide-ranging research project presented in this dissertation. Quotations from Horace and references to his oeuvre have been divided according to the function they perform in the poetics manuals, the aim of which was to teach pupils how to compose Latin poetry. Three main aspects have been identified: the first consists of theoretical recommendations useful to the would-be poets, which are taken mainly from Horace’s Ars poetica. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center

THE AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE CENTER STUDY GUIDE Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center. All rights reserved. The following materials were compiled by the Education and Research Department of the American Shakespeare Center, 2015. Created by: Cass Morris, Academic Resources Manager; Sarah Enloe, Director of Education and Research; Ralph Cohen, ASC Executive Founding Director and Director of Mission; Jim Warren, ASC Artistic Director; Jay McClure, Associate Artistic Director; ASC Actors and Interns. Unless otherwise noted, all selections from Julius Caesar in this study guide use the stage directions as found in the 1623 Folio. All line counts come from the Norton Shakespeare, edited by Stephen Greenblatt et al, 1997. The American Shakespeare Center is partially supported by a grant from the Virginia Commission for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. American Shakespeare Center Study Guides are part of Shakespeare for a New Generation, a national program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest. -2- Dear Fellow Educator, I have a confession: for almost 10 years, I lived a lie. Though I was teaching Shakespeare, taking some joy in pointing out his dirty jokes to my students and showing them how to fight using air broadswords; though I directed Shakespeare productions; though I acted in many of his plays in college and professionally; though I attended a three-week institute on teaching Shakespeare, during all of that time, I knew that I was just going through the motions. Shakespeare, and our educational system’s obsession with him, was still a bit of a mystery to me. -

A History of the New Testament Times

^'11. .:^^- %/., 'y, 'k PRINCETON, N. J. BS 2410 .H3"8i3'^i878 v.l Hausrath, Adolf, 1837-1909. A history of the New Shelf.. Testament times A HISTORY NEW TESTAMENT TIMES. DR A. '^AUSEATH, OIIDINARY PROFESSOR OF THEOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF HEIDELBERa. THE TIME OF JESUS. VOL. I. TRANSLATED, WITH THE AUTHORS SANCTION, FROM THE SECOND GERMAN EDITION, BY CHARLES T. POINTING, B.A, & PHILIP QUENZER. WILLIAMS AND N R G A T E, 14, HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN, LONDON; And 20, SOUTH FREDERICK STREET, EDINBURGH. 1878. : LONDON PRINTED BY 0. GREEN AND SON, 178, STRAND. THE TIME OF JESUS. VOL. I. : XM'^^^ic^ PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The History of the New Testament Times is now presented to tlie reader in a revised and enlarged edition. The latter part of the work, especially, has at the same time been much altered under the influence of Dr. Keim's Jesus of Nazara. In the plan of the book nothing has been altered. The aim in view is still to present a history of the development of culture in the times of Jesus and the writers of the New Testa- ment, so far as this development had a direct influence upon the rise of Christianity ; and then to give the history of this rise itself, so far as it can be treated as an objective history, and not as a subjective religious process. The author, in the Preface to the first edition, wrote as follows " "What we call the sacred history, is the presentation of only the most prominent points of a far broader historical life. -

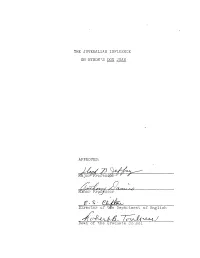

The Juvenalian Influence on Byronts Don Juan Approved

THE JUVENALIAN INFLUENCE ON BYRONTS DON JUAN APPROVED: \ Minor Professor Director of tfefe Department of English Dean of the Graduate Sci'iool THE JUVENALIAN INFLUENCE ON BYRON'S DON JUAN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Diane Gardner Dunson, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1967 PREFACE This thesis is a comparative study of Juvenal and Lord Byron, with emphasis on the particularly kindred aspects of the poets' works. The two men lived hundreds of years apart, yet their ideas and attitudes are so similar that the con- nection bears research. In many instances, the relationship between the poets is only temperamental; at other times, the subject matter of Byron reveals the direct influence of Ju- venal. This paper treats in detail the major topics of in- terest which Juvenal and Byron shared—society, morality, war, death, and the purpose of life. The first chapter on' the nature of satire serves as an introduction to the study of these topics and is designed to bridge the time gap be- tween the poets. The backgrounds of Juvenal and Byron are considered briefly to show the comparable social and politi- cal atmosphere of their early manhood. The remaining three chapters deal in detail with the subject matter of Juvenal's Satires and Byron's Don Juan, with emphasis on the modernity, soundness of judgement, and worth of that which the two men have to say. For the particular study of the Juvenalian influence on Lord Byron, and especially on Don Juan, there were no iii specific books available. -

Flexsenhar-Mastersreport

Copyright by Michael A. Flexsenhar III 2013 The Report Committee for Michael A. Flexsenhar III Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis report: No Longer a Slave: Manumission in the Social World of Paul APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: L. Michael White Steven J. Friesen No Longer a Slave: Manumission in the Social World of Paul by Michael A. Flexsenhar III, B.A., M.T.S. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication In memoriam Janet Ruth Flexsenhar mea avia piissima Abstract No Longer a Slave: Manumission in the Social World of Paul Michael A. Flexsenhar III, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2013 Supervisor: L. Michael White The Roman Empire was a slave society. New Testament and Early Christian scholars have long recognized that slaves formed a substantial portion of the earliest Christian communities. Yet there has been extensive debate about manumission, the freeing of a slave, both in the wider context of the Roman Empire and more specifically in Paul’s context. 1 Cor. 7:20-23 is a key passage for understanding both slavery and manumission in Pauline communities, as well as Paul’s own thoughts on these two contentious issues. The pivotal verse is 1 Cor. 7:21. The majority opinion is that Paul is suggesting slaves should become free, i.e., manumitted, if they are able. In order to better understand this biblical passage and its social implications, this project explores the various types of manumissions operative the Roman world: the legal processes and results; the factors that galvanized and constrained manumissions; the political and social environment surrounding manumission in Corinth during Paul’s ministry; as well as the results of manumission as it relates to Paul’s communities. -

Liberation and Liberality in Roman Funerary Commemoration

This is a repository copy of "The mourning was very good". Liberation and liberality in Roman funerary commemoration. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/138677/ Version: Published Version Book Section: Carroll, P.M. (2011) "The mourning was very good". Liberation and liberality in Roman funerary commemoration. In: Hope, V.M. and Huskinson, J., (eds.) Memory and Mourning: Studies on Roman Death. Oxbow Books Limited , pp. 125-148. ISBN 9781842179901 © 2011 Oxbow Books. Reproduced in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 8 ‘h e mourning was very good’. Liberation and Liberality in Roman Funerary Commemoration Maureen Carroll h e death of a slave-owner was an event which could bring about the most important change in status in the life of a slave. If the last will and testament of the master contained the names of any fortunate slaves to be released from servitude, these individuals went from being objects to subjects of rights. -

L 049 Strabo Geography I

Google This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non- commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Download Horace: the SATIRES, EPISTLES and ARS POETICA

+RUDFH 4XLQWXV+RUDWLXV)ODFFXV 7KH6DWLUHV(SLVWOHVDQG$UV3RHWLFD Translated by A. S. Kline ã2005 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non- commercial purpose. &RQWHQWV Satires: Book I Satire I - On Discontent............................11 BkISatI:1-22 Everyone is discontented with their lot .......11 BkISatI:23-60 All work to make themselves rich, but why? ..........................................................................................12 BkISatI:61-91 The miseries of the wealthy.......................13 BkISatI:92-121 Set a limit to your desire for riches..........14 Satires: Book I Satire II – On Extremism .........................16 BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes............................................................................16 BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery ..........................................................................................17 BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague.17 BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble...............................................................................18 BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles.............19 BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!..................20 Satires: Book I Satire III – On Tolerance..........................22 BkISatIII:1-24 Tigellius the Singer’s faults......................22 BkISatIII:25-54 Where is our tolerance though? ..............23 BkISatIII:55-75 -

The Sophistic Roman: Education and Status in Quintilian, Tacitus and Pliny Brandon F. Jones a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

The Sophistic Roman: Education and Status in Quintilian, Tacitus and Pliny Brandon F. Jones A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Alain Gowing, Chair Catherine Connors Alexander Hollmann Deborah Kamen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics ©Copyright 2015 Brandon F. Jones University of Washington Abstract The Sophistic Roman: Education and Status in Quintilian, Tacitus and Pliny Brandon F. Jones Chair of Supervisory Commitee: Professor Alain Gowing Department of Classics This study is about the construction of identity and self-promotion of status by means of elite education during the first and second centuries CE, a cultural and historical period termed by many as the Second Sophistic. Though the Second Sophistic has traditionally been treated as a Greek cultural movement, individual Romans also viewed engagement with a past, Greek or otherwise, as a way of displaying education and authority, and, thereby, of promoting status. Readings of the work of Quintilian, Tacitus and Pliny, first- and second-century Latin prose authors, reveal a remarkable engagement with the methodologies and motivations employed by their Greek contemporaries—Dio of Prusa, Plutarch, Lucian and Philostratus, most particularly. The first two chapters of this study illustrate and explain the centrality of Greek in the Roman educational system. The final three chapters focus on Roman displays of that acquired Greek paideia in language, literature and oratory, respectively. As these chapters demonstrate, the social practices of paideia and their deployment were a multi-cultural phenomenon. Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................... 2 Introduction ....................................................................................... 4 Chapter One. -

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate from the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate From the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty By Jessica J. Stephens A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, chair Professor Bruce W. Frier Professor Richard Janko Professor Nicola Terrenato [Type text] [Type text] © Jessica J. Stephens 2016 Dedication To those of us who do not hesitate to take the long and winding road, who are stars in someone else’s sky, and who walk the hillside in the sweet summer sun. ii [Type text] [Type text] Acknowledgements I owe my deep gratitude to many people whose intellectual, emotional, and financial support made my journey possible. Without Dr. T., Eric, Jay, and Maryanne, my academic career would have never begun and I will forever be grateful for the opportunities they gave me. At Michigan, guidance in negotiating the administrative side of the PhD given by Kathleen and Michelle has been invaluable, and I have treasured the conversations I have had with them and Terre, Diana, and Molly about gardening and travelling. The network of gardeners at Project Grow has provided me with hundreds of hours of joy and a respite from the stress of the academy. I owe many thanks to my fellow graduate students, not only for attending the brown bags and Three Field Talks I gave that helped shape this project, but also for their astute feedback, wonderful camaraderie, and constant support over our many years together. Due particular recognition for reading chapters, lengthy discussions, office friendships, and hours of good company are the following: Michael McOsker, Karen Acton, Beth Platte, Trevor Kilgore, Patrick Parker, Anna Whittington, Gene Cassedy, Ryan Hughes, Ananda Burra, Tim Hart, Matt Naglak, Garrett Ryan, and Ellen Cole Lee.