L 049 Strabo Geography I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17Th-First Half of the 18Th Century

The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Siedina, Giovanna. 2014. The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13065007 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2014 Giovanna Siedina All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Author: Professor George G. Grabowicz Giovanna Siedina The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century Abstract For the first time, the reception of the poetic legacy of the Latin poet Horace (65 B.C.-8 B.C.) in the poetics courses taught at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy (17th-first half of the 18th century) has become the subject of a wide-ranging research project presented in this dissertation. Quotations from Horace and references to his oeuvre have been divided according to the function they perform in the poetics manuals, the aim of which was to teach pupils how to compose Latin poetry. Three main aspects have been identified: the first consists of theoretical recommendations useful to the would-be poets, which are taken mainly from Horace’s Ars poetica. -

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

Docuwatch Digitales Fernsehen

DocuWatch Digitales Fernsehen Im Auftrag der Landesmedienanstalten 2/99 1. AUSTRALIEN: ÜBERGANG ZU DIGITALER VERBREITUNG UND FELDVERSUCHE 2 2. JAPAN: WEIßBUCH “COMMUNICATIONS IN JAPAN” U.A. 4 3. FRANKREICH: STUDIE UND WEIßBUCH ZUM TERRESTRISCHEN DIGITALEN FERNSEHEN 6 4. EINZELTHEMEN 8 4.1. Großbritannien: ITC und OFTEL zum Bundling 8 4.2. Großbritannien: ITC zum Vorschlag einer Gebührenerhöhung bei digitalem Empfang 8 4.3. Großbritannien: Reaktionen auf das britische Konvergenz-Grünbuch 9 4.4. Großbritannien: ITC Guidelines für Gebärdensprache im DTV 9 4.5. Singapur übernimmt DVB-Standard 9 4.6. USA: V-Chip Implementation verläuft planmäßig 9 4.7. USA: Department of Commerce zu E-Business 9 4.8. Communications Regulatory Policy Unit der DG XIII: Multimedia Regulation 10 4.9. LfK: Bericht über Erprobungsprojekt Mediendienste 10 5. LITERATURHINWEISE 11 5.1. Zeitschriften 11 5.2. Buchveröffentlichungen 13 6. ANHÄNGE 15 6.1. Anzahl der Abonnenten von Programmpaketen /1993-1998 16 6.2. Digitale Satelliten-Programmpakete / Februar 1999 17 Zum DocuWatch Um die Entwicklung digitalen Fernsehens begleiten zu können, benötigen Entscheidungsträger bei den Regulierungsinstanzen ebenso wie alle anderen Beobachter kontinuierlich Informationen. Das Hans- Bredow-Institut sichtet im Auftrag der Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Landesmedienanstalten (ALM) Dokumente aus dem wissenschaftlichen Bereich sowie von Regulierungsinstanzen, in- und ausländischen sowie supra- nationalen Organisationen und Verbänden und erstellt Zusammenfassungen, die auf die für die Arbeit der Landesmedienanstalten relevanten Fragen focussiert sind. Im Mittelpunkt stehen dabei neben inländischen Institutionen solche aus den USA, Kanada, Großbritannien und Frankreich. Daneben wird die am Institut gesammelte wissenschaftliche Literatur ausgewertet. Arbeitsgruppe digitales Fernsehen am Hans-Bredow-Institut Uwe Hasebrink, Friedrich Krotz, Wolfgang Schulz sowie Fernando Reimann Redaktionsschluß 31. -

Guide Des Chaînes Numériques

Guide des chaînes numériques A.C.C.e.S. Mars 2008 Association des Chaînes Conventionnées éditrices de Services A.C.C.e.S. 17, rue de l’Amiral Hamelin 75116 Paris Tel : 01.47.04.24.09 - Fax : 01.47.04.27.94 www.acces.tv Avec la participation de : Centre National de la Cinématographie Syndicat National de la Publicité TéléVisée Direction de l'audiovisuel 1, quai du Point du Jour 92656 Boulogne Cedex Direction des études, des statistiques et de la prospective Tél. : 01.41.41.43.21 - Fax : 01.41.41.43.30 12, rue de Lübeck 75784 Paris Cedex 16 Mail : [email protected] Tél. : 01.44.34.38.26 - Fax : 01.44.34.34.55 www.snptv.org www.cnc.fr avec la collaboration de Médiamétrie pour les Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel données d'audiences : Direction des études et de la prospective 55-63, rue Anatole France Direction des opérateurs audiovisuels 92532 Levallois Perret Cedex Direction des programmes Tél. : 01.47.58.97.58 Tour Mirabeau www.mediametrie.fr 39-43, quai André Citroën 75739 Paris Cedex 15 Tél. : 01.40.58.38.00 www.csa.fr Réalisé par : Direction du Développement des Médias Scholè Marketing 69, rue de Varenne 75348 Paris 07 SP 46, Place Jules-Ferry 92120 Montrouge www.ddm.gouv.fr Tél. : 01.71.16.15.80 - Fax : 01.46.55.70.07 Tél. : 01.42.75.82.00 www.schole.fr 2 Guide des chaînes numériques Sommaire SOMMAIRE.............................................................................................................................. 3 AVANT-PROPOS...................................................................................................................... 5 LE CADRE REGLEMENTAIRE...................................................................................................... 7 I. Textes de référence ..................................................................................................... 7 II. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

A History of the New Testament Times

^'11. .:^^- %/., 'y, 'k PRINCETON, N. J. BS 2410 .H3"8i3'^i878 v.l Hausrath, Adolf, 1837-1909. A history of the New Shelf.. Testament times A HISTORY NEW TESTAMENT TIMES. DR A. '^AUSEATH, OIIDINARY PROFESSOR OF THEOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF HEIDELBERa. THE TIME OF JESUS. VOL. I. TRANSLATED, WITH THE AUTHORS SANCTION, FROM THE SECOND GERMAN EDITION, BY CHARLES T. POINTING, B.A, & PHILIP QUENZER. WILLIAMS AND N R G A T E, 14, HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN, LONDON; And 20, SOUTH FREDERICK STREET, EDINBURGH. 1878. : LONDON PRINTED BY 0. GREEN AND SON, 178, STRAND. THE TIME OF JESUS. VOL. I. : XM'^^^ic^ PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The History of the New Testament Times is now presented to tlie reader in a revised and enlarged edition. The latter part of the work, especially, has at the same time been much altered under the influence of Dr. Keim's Jesus of Nazara. In the plan of the book nothing has been altered. The aim in view is still to present a history of the development of culture in the times of Jesus and the writers of the New Testa- ment, so far as this development had a direct influence upon the rise of Christianity ; and then to give the history of this rise itself, so far as it can be treated as an objective history, and not as a subjective religious process. The author, in the Preface to the first edition, wrote as follows " "What we call the sacred history, is the presentation of only the most prominent points of a far broader historical life. -

Comcast Channel Lineup

• Basi.c Service , $ 14.99 Equipment and Options (prices per month) The minimum level of service available and is required before you HOTV Equipment Charge~ ... .., ...............•.........$ 7.00 can subscribe to additional services, HO OVR Service .................•........................$ 15.95 SO DVR Service ..................................•........$ 8.95 Starter Cable , $ 55.99 Digital/Analog Converter . .. .....................•........$ 3.20 Includes Starter Cable channels plus OCT & Remote. Analog Converter for Basic Service Only ......•............ " .$ 1.00 Digital/Analog Remote Control . .•.......•.. ,... .$ 0.20 Digital Preferred ,,,,, $ 16.95 This package can be added to Starter Cable and includes the Installation and Service' channels in Digital Classic. Home Installation (Wired) ......., .......•........ , .$ 23.99 Home InstaiJation (Unwired) ............................•... .$ 33.99 Digital Preferred Plus Package , $ 107.99 Additional Connection at Time of Imliallnstall , $ 12.99 Includes the channels in Starter Cable. Digital Classic, and HBO Additional Connection Requiring Separate Trip ..........•.....$ 20.99 and STARZl. Move Outlet ........................................•. , ..$ 16.99 Upgrade of Services _.......•.. , ..$ 14.99 Digital Premier Package , ,.$ 127,99 Downgrade of Services ,... .. , ..........•.........•....$ 10.95 Includes the channels in Starter Cable, Digital Classic, Sports Change of Service or Equipment Activation ........•......•.....$ 1.99 Entertainment Tier, HBO, Showtime, Cinemax and Starzl. Connect VCR at Time of InitiallnstaiJ $ 5.99 Connect VCR Requiring Separate Trip .................•......$ 12.99 Digital Premium Services. ,,,,, $ 19.99 Hourly Service Charge. .........,.. $ 30.99 Premium services can be added to any Digital package, Select Service Call Trip Charge ........ $ 27.20 from HBO, Showtime, Cinemax, The Movie Channel, STARZI Administrative Fee for Delinquent Accounts at 30 Days $ 5.95 or E(1core. Administrative Fee for Delinquent Accounts at 60 Days ,$ 5.95 Additional Late Fee Every 30 Days After. -

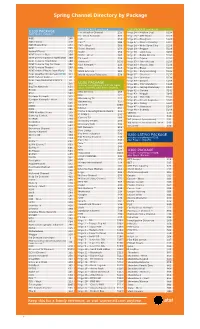

Spring Channel Directory by Package

Spring Channel Directory by Package U100 PACKAGE continued: U200 PACKAGE continued: U100 PACKAGE The Weather Channel 225 Urge 24 – Modern Soul 5124 (with locals) includes: The Word Network 575 Urge 25 – CMT Radio 5125 A&E 166 TLC 250 Urge 26 – Bluegrass 5126 ABC Family 178 TNT ** 108 Urge 27 – Classic Country 5127 ABC News Now 243 TNT - West ** 109 Urge 28 – Wide Open Ctry 5128 AMC * 795 Travel Channel 254 Urge 29 – Reggae 5129 Animal Planet 252 TruTV 164 Urge 30 – Latin Jazz 5130 AT&T U-verse Buzz 300 TruTV - West 165 Urge 31 – Radio Alterna 5131 AT&T U-verse Customer Notification 400 TV Land 138 Urge 32 – Tejano 5132 AT&T U-verse Front Row 100 Univision * 3002 Urge 33 – Smooth Jazz 5133 AT&T U-verse Pay Per View 102 USA Network ** 124 Urge 34 – Classic Jazz 5134 AT&T U-verse Theatre 200 VH1 518 Urge 35 – Blues 5135 AT&T Online Photos from Flickr 91 WGN America ** 180 Urge 36 – Easy Listening 5136 AT&T Weather On Demand NEW! 227 World Harvest Television 578 Urge 37 – Classical 5137 AT&T Yahoo! Games 92 Urge 38 – Christian 5138 AT&T YELLOWPAGES.COM TV 97 Urge 39 – Gospel 5139 BET 155 U200 PACKAGE Urge 40 – POP Standards 5140 includes everything in U100, 48 digital Big Ten Network ** 650 music channels, plus these channels: Urge 41 – Jazzup Broadway 5141 Bravo 181 Urge 42 – Cinema 5142 BBC America 188 BYU 567 Urge 43 – Noggin 5143 BIO 272 Cartoon Network 325 Urge 44 – Nick Kids 5144 Bloomberg TV 222 Cartoon Network - West 326 Urge 45 – Dream Sequence 5145 Boomerang 327 CMT 525 Urge 46 – Swing 5146 CCTV-9 3602 CNBC 216 Urge 47 – Showcase -

Goodland Star-News

The MIDWEEK Tuesday, Jan. 5 Goodland Star-News 2021 1205MainAvenue,Goodland,KS67735•Phone(785)899-2338 $1 Volume 89, Number 1 8 Pages Goodland, Kansas 67735 upcoming Health Not quite a white Christmas event department Groundwater recommends meeting masks The Northwest Kansas The Sherman County Health Groundwater Management Department is continuing to recom - District No. 4 – which includes mend citizens wear masks in public Sherman County – will hold its places where social distancing can- annual meeting on Wednesday, not be maintained. Feb. 10, at the City Limits The department is following Convention Center in Colby. Kansas Department of Health and Election voting will begin at 11 Environment recommendations a.m. (Mountain Time) with the when it comes to masks, and said meeting starting at 12:30 p.m. they should be worn in public set- Topics include the 2020 year in tings when around people who review, 2020 financial report, don’t live in your household and election of board positions, especially when it is difficult to stay presentation by Mammoth more than six feet apart. Water of their meter tracking The department has also been app, and other items of interest. getting a lot of questions about the Everyone is invited to attend. COVID-19 vaccines. For more information, visit The department has administered www.gmd4.org or contactthe allthe doses of the vaccine that it has district office at 1290 West received to area healthcare workers Fourth Street, Colby, Kansas, and assisted living residents and 785-462-3915 or e-mailing staff. There are a few healthcare Shannon Kenyon at skenyon@ workers still waiting to receive their gmd4.org. -

Arcanum Imperii 1 a Script for Cthulhu Live 3Rd Edition by Robert “Mac” Mclaughlin and the Skirmisher Game Development Group

Sample file Arcanum Imperii 1 A Script for Cthulhu Live 3rd Edition By Robert “Mac” McLaughlin and the Skirmisher Game Development Group Skirmisher Publishing LLC P.O. Box 150006 Alexandria, VA 22315-0006 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.skirmisher.com Interactive Forum: http://www.skirmisher.com Game Store: http://skirmisher.cerizmo.com Publishers: Robert “Mac” McLaughlin, Michael J. Varhola, Geoff Weber Editors: Robert “Mac” McLaughlin, Michael J. Varhola, Layout and Design: Jessica McDevitt, Michael J. Varhola and Bradley K. McDevitt (Cover) PDF Publications Manager: Jessica McDevitt CoverSample image: A Reading from Homer, by Sir Lawrence fileAlma-Tadema (1885). Other images throughout this book appear courtesy of Bradley K. McDevitt (pp. 1, 11), PST Productions (pp. 5, 6, 8-10, 12), or are in the public domain. Copyright 2009 by Skirmisher Publishing LLC. All rights reserved. First Skirmisher PDF Edition: January 2009 SKP E 0901 2 Cthulhu Live 3rd Edition Title Page ......................................1 Macedonian Nobles and Servants .30 Credits Page ..................................2 Xanthippus .................................30 Megacles .....................................31 Table of Contents .........................3 Parmenion ...................................32 Cepheus ......................................35 Cast of Characters .......................4 Olympias ....................................35 Prologue ........................................5 Arrian ..........................................37 -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA. -

Studies in Pausanias' Periegesis Akujärvi, Johanna

Researcher, Traveller, Narrator : Studies in Pausanias' Periegesis Akujärvi, Johanna 2005 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Akujärvi, J. (2005). Researcher, Traveller, Narrator : Studies in Pausanias' Periegesis. Almqvist & Wiksell International. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Studia Graeca et Latina Lundensia 12 Researcher, Traveller, Narrator Studies in Pausanias’ Periegesis Johanna Akujärvi Lund 2005 Almqvist & Wiksell International Stockholm/Sweden © 2005 Johanna Akujärvi Distributed by Almqvist & Wiksell International P.O. Box 7634 S-103 94 Stockholm Sweden Phone: + 46 8 790 38 00 Fax: + 46 8 790 38 05 E-mail: [email protected] ISSN 1100-7931 ISBN 91-22-02134-5 Printed in Sweden Media-Tryck, Lund University Lund 2005 To Daniel Acknowledgements There are a number of people to whom I wish to express my gratitude.