Transformation and Secularization in an Ewe Funeral Drum Tradition *Ecompanion At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music of Ghana and Tanzania

MUSIC OF GHANA AND TANZANIA: A BRIEF COMPARISON AND DESCRIPTION OF VARIOUS AFRICAN MUSIC SCHOOLS Heather Bergseth A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERDecember OF 2011MUSIC Committee: David Harnish, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2011 Heather Bergseth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Harnish, Advisor This thesis is based on my engagement and observations of various music schools in Ghana, West Africa, and Tanzania, East Africa. I spent the last three summers learning traditional dance- drumming in Ghana, West Africa. I focus primarily on two schools that I have significant recent experience with: the Dagbe Arts Centre in Kopeyia and the Dagara Music and Arts Center in Medie. While at Dagbe, I studied the music and dance of the Anlo-Ewe ethnic group, a people who live primarily in the Volta region of South-eastern Ghana, but who also inhabit neighboring countries as far as Togo and Benin. I took classes and lessons with the staff as well as with the director of Dagbe, Emmanuel Agbeli, a teacher and performer of Ewe dance-drumming. His father, Godwin Agbeli, founded the Dagbe Arts Centre in order to teach others, including foreigners, the musical styles, dances, and diverse artistic cultures of the Ewe people. The Dagara Music and Arts Center was founded by Bernard Woma, a master drummer and gyil (xylophone) player. The DMC or Dagara Music Center is situated in the town of Medie just outside of Accra. Mr. Woma hosts primarily international students at his compound, focusing on various musical styles, including his own culture, the Dagara, in addition music and dance of the Dagbamba, Ewe, and Ga ethnic groups. -

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

Field Test of New Features & Adaptations Based on On- Going Feedback

FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON- GOING FEEDBACK USAID/GHANA JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM CASE TRACKING SYSTEM ACTIVITY October 29, 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON- GOING FEEDBACK USAID/GHANA JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM CASE TRACKING SYSTEM ACTIVITY Contract No. AID-OOA-I-13-00032, Task Order No. 72064118F00001 Cover photo: Training session for staff of the Economic and Organised Crime Office (EOCO), Ho regional office on 14 May 2019. (Credit: Samuel Akrofi, Ghana Case Tracking System Activity) I FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON-GOING FEEDBACK ACRONYMS ADKAR Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, Reinforcement BNI Bureau of National Investigations CLIN Contract Line Item Number CTS Case Tracking System EOCO Economic and Organized Crime Office FDA Food and Drug Authority FP Focal Point GoG Government of Ghana IBG Inter-regional Bridge Group ICT Information and Communications Technology GPoS Ghana Police Service GPrS Ghana Prison Service GRA Ghana Revenue Authority JSG Judicial Service of Ghana KSA Key Stakeholder Agency LAC Legal Aid Commission MOJ/DPP Ministry of Justice/Department of Public Prosecution PWA Performance Work Statement SGI Security and Governance Initiative SIE System Implementation Engineer(s) TDA Transnational Development Associates UAT user acceptance test USAID United States Agency for International Development TABLE OF -

David Laurence Locke Professor of Music

1 David Laurence Locke Professor of Music Tufts University Department of Music 19 Sagamore Avenue The Perry and Marty Granoff Music Center Medford, MA 02155 20 Talbot Ave. 781-483-3820 Medford, MA 02155 [email protected] 617-627-2419 EDUCATION Wesleyan University, Ph.D., Ethnomusicology, 1978 -Dissertation, "The Music of Atsiagbekor," supervised by David McAllester; fieldwork in Ghana (1975-1977) supervised by J.H. Kwabena Nketia. Wesleyan University, B.A., High Honors, Anthropology, 1972 -Thesis, "Jerk Pork," based on fieldwork in Jamaica (1971). ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT Tufts University, Music Department, 1993-present -Department Chair 1994-2000 -Director of Graduate Studies, 2011-2012 Tufts University, Music Department (0.75 FTE) and Dance Program, Department of Drama and Dance (0.25 FTE), Assistant Professor, 1986-1992 Tufts University, Music Department, Dance Program, Lecturer (part-time), 1979- 1985 PUBLICATIONS Books Agbadza: Songs, Drum Language of the Ewes, with compact disc. African Music Publishers, 2013 The Agbadza Project of Gideon Foli Alorwoyie. Published by Tufts Digital Archive, 2012. http://sites.tufts.edu/davidlocke/Agbadza. Dagomba Dance Drumming. Published by Tufts Digital Archive, 2010. http://sites.tufts.edu/davidlocke/Dagomba. Kpegisu: A War Drum of the Ewe, with audio compact disc and video, White Cliffs Media Company, 1992. Drum Damba: Talking Drum Lessons, with audio compact disc, White Cliffs Media Company, 1990. Drum Gahu: A Systematic Method for an African Drum Piece, with audio compact disc, White Cliffs Media Company, 1988. A Collection of Atsiagbekor Songs, Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, 1980. 2 Books: Co-author G. Foli Alorwoyie with David Locke. -

BY DOE HEDE RICHMOND B.Ed (MATHEMATICS) a Thesis

LOCATION OF NON-OBNOXIOUS FACILITY (HOSPITAL) IN KETU SOUTH DISTRICT BY DOE HEDE RICHMOND B.Ed (MATHEMATICS) A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Mathematics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Award of Master of Science in Industrial Mathematics. OF COLLEGE OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES INSTITUTE OF DISTANCE LEARNING MAY, 2013 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my own original research with close supervisor by my supervisor and that no part of it has been presented to any institution or organization anywhere for the award of Mastersdegree. All inclusive for the work of others has been duly acknowledged. Doe Hede Richmond (PG4065110) Student …………………… ………………… Signature Date Certified by; Mr. K. F. Darkwah Supervisor’s …………………… ………………… Signature Date Certified by; Mr. K. F. Darkwah …………………… ………………… Head of Department Signature Date ii ABSTRACT The main purpose of this research is to model the location of two emergency hospitals for Ketu South district due to the newness of the district. This is to help solve the immediate health needs of the people in the district. One essential way of doing this is to locate two hospitals which will be closer to all the towns and villages in order to reduce the cost of travelling and the distances people have to access the facilities (hospital). In doing this, p-median and heuristics(RH1, RH2 and RRH) were employed to minimize the distances people have to travel to the demand point (hospitals) to access the facilities. Floyd-warshall algorithm was also adopted to connect the ten (10) selected towns and villages together. -

“I Want to Go to School, but I Can't”: Examining the Factors That Impact

―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana A dissertation presented to the faculty of The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Karen Yawa Agbemabiese-Grooms August 2011 © 2011 Karen Yawa Agbemabiese-Grooms. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled ―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana by KAREN YAWA AGBEMABIESE-GROOMS has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services by Jaylynne N. Hutchinson Associate Professor of Educational Studies Renée A. Middleton Dean, The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services 3 Abstract AGBEMABIESE-GROOMS, KAREN YAWA, Ph.D., August 2011, Curriculum and Instruction, Cultural Studies ―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana (pp. 306) Director of Dissertation: Jaylynne N. Hutchinson This study explored factors that impact the Anlo Ewe girl child‘s formal educational outcomes. The issue of female and girl child education is a global concern even though its undesirable impact is more pronounced in African rural communities (Akyeampong, 2001; Nukunya, 2003). Although educational research in Ghana indicates that there are variables that limit girl‘s access to formal education, educational improvements are not consistent in remedying the gender inequities in education. -

A Study of the Ewe Unification Movement in the United States

HOME AWAY FROM HOME: A STUDY OF THE EWE UNIFICATION MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES BY DJIFA KOTHOR THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Master’s Committee: Professor Faranak Miraftab, Chair Professor Kathryn Oberdeck Professor Alfred Kagan ABSTRACT This master’s thesis attempts to identity the reasons and causes for strong Ewe identity among those in the contemporary African Diaspora in the United States. An important debate among African nationalists and academics argues that ethnic belonging is a response to colonialism instigated by Western-educated African elites for their own political gain. Based on my observation of Ewe political discourses of discontent with the Ghana and Togolese governments, and through my exploratory interviews with Ewe immigrants in the United States; I argue that the formation of ethnic belonging and consciousness cannot be reduced to its explanation as a colonial project. Ewe politics whether in the diaspora, Ghana or Togo is due to two factors: the Ewe ethnonational consciousness in the period before independence; and the political marginalization of Ewes in the post-independence period of Ghana and Togo. Moreover, within the United States discrimination and racial prejudice against African Americans contribute to Ewe ethnic consciousness beyond their Togo or Ghana formal national belongings towards the formation of the Ewe associations in the United States. To understand the strong sense of Ewe identity among those living in the United States, I focus on the historical questions of ethnicity, regionalism and politics in Ghana and Togo. -

They're Ghana Love It!: Experiences with Ghanaian Music for Middle

They’re Ghana Love It!: Experiences with Ghanaian Music for Middle School General Music Students A Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed by: James B. Morford Puyallup School District - Puyallup, WA Summary: This lesson is intended to develop knowledge regarding Ghanaian music. Students will experience the musical cultures of Ghana through listening, movement, game play, and percussion performance. Lesson segments are designed to stand alone, but sequential presentation may yield greater success as the experiences progress toward more rigorous performance requirements for both the students and instructor. Suggested Grade Levels: 6-8 Country: Ghana Region: West Africa Culture Group: Akan, Dagomba, Ewe, Ga Genre: World Instruments: Voice, Body Percussion, Gankogui, Axatse, Kidi, Kagan (or substitutes as suggested) Language: N/A Co-Curricular Areas: Geography, Social Studies National Standards: 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 9 Prerequisites: Experience playing and reading music in 6/8 time Objectives: Listening to and viewing musical expressions Identifying cultural and musical traits of Ghanaian music Understanding the role of a common fundamental bell pattern Identifying aurally presented rhythms using written notation Playing a Ghanaian children’s game Performing traditional/folkloric polyrhythmic structures Materials: Fontomfrom, SFW40463_106 http://www.folkways.si.edu/rhythms-of-life-songs-of-wisdom-akan- music-from-ghana/world/album/smithsonian Gondze Praise Music (2), FW04324_103 http://www.folkways.si.edu/music-of-the-dagomba-from- ghana/world/album/smithsonian Music of the Dagomba from Ghana, FW04324 (liner notes) http://media.smithsonianfolkways.org/liner_notes/folkways/FW04324.p df Brass Band: Yesu ye medze/Nyame ye osahen, SFW40463_109 http://www.folkways.si.edu/rhythms-of-life-songs-of-wisdom-akan- music-from-ghana/world/album/smithsonian Rhythms of Life, Songs of Wisdom, SFW40463 (liner notes) http://media.smithsonianfolkways.org/liner_notes/smithsonian_folkway s/SFW40463.pdf M. -

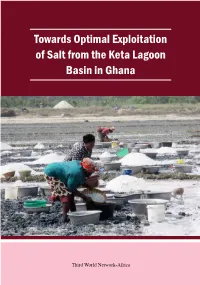

Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana

Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana Third World Network-Africa Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana Third World Network-Africa Accra, Ghana Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana is published by Third World Network-Africa No 9 Asmara Street, East Legon, Accra Box AN 19452, Accra, Ghana Tel: 233-302-500419/503669/511189 Website: www.twnafrica.org Email: [email protected] Copyright © Third World Network-Africa, 2017 ISBN: 9988271305 Foreword Ghana has the best endowment for and is the biggest producer of solar salt in West Africa. The bulk of the production and export comes from arti- sanal and small scale (ASM) producers. This is a research report on strug- gles between a large scale salt company and some communities around the Keta Lagoon in Ghana. At the centre of the conflict is the disruption of the livelihoods of the communities by the award of a concession to a foreign investor for large scale salt production, an act which has expropri- ated what the communities see as the commons around the lagoon where for generations they have carried out livelihood activities which combine fishing, farming and salt production. The Keta Lagoon is the second most important salt producing area in Ghana and the conflict, in which Police protecting the company have shot some locals dead, is emblematic of the wider problem of the status of ASM across Africa with many governments even when faced with the huge potential of ASM avoid offering support to these predominantly lo- cal entrepreneurs and reflexively choose to support large scale, usually foreign, investors. -

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names The vernacular names listed below have been collected from the literature. Few have phonetic spellings. Spelling is not helped by the difficulties of transcribing unwritten languages into European syllables and Roman script. Some languages have several names for the same species. Further complications arise from the various dialects and corruptions within a language, and use of names borrowed from other languages. Where the people are bilingual the person recording the name may fail to check which language it comes from. For example, in northern Sahel where Arabic is the lingua franca, the recorded names, supposedly Arabic, include a number from local languages. Sometimes the same name may be used for several species. For example, kiri is the Susu name for both Adansonia digitata and Drypetes afzelii. There is nothing unusual about such complications. For example, Grigson (1955) cites 52 English synonyms for the common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in the British Isles, and also mentions several examples of the same vernacular name applying to different species. Even Theophrastus in c. 300 BC complained that there were three plants called strykhnos, which were edible, soporific or hallucinogenic (Hort 1916). Languages and history are linked and it is hoped that understanding how lan- guages spread will lead to the discovery of the historical origins of some of the vernacular names for the baobab. The classification followed here is that of Gordon (2005) updated and edited by Blench (2005, personal communication). Alternative family names are shown in square brackets, dialects in parenthesis. Superscript Arabic numbers refer to references to the vernacular names; Roman numbers refer to further information in Section 4. -

Certified Electrical Wiring Professionals Volta Regional Register Certification No

CERTIFIED ELECTRICAL WIRING PROFESSIONALS VOLTA REGIONAL REGISTER CERTIFICATION NO. NAME PHONE NUMBER PLACE OF WORK PIN NUMBER CLASS 1 ABOTSI FELIX GBOMOSHOW 0246296692 DENU EC/CEWP1/06/18/0020 DOMESTIC 2 ACKUAYI JOSEPH DOTSE 0244114574 ANYAKO EC/CEWP1/12/14/0021 DOMESTIC 3 ADANU KWASHIE WISDOM 0245768361 DZODZE, VOLTA REGION EC/CEWP1/06/16/0025 DOMESTIC 4 ADEVOR FRANCIS 0241658220 AVE-DAKPA EC/CEWP1/12/19/0013 DOMESTIC 5 ADISENU ADOLF QUARSHIE 0246627858 AGBOZUME EC/CEWP1/12/14/0039 DOMESTIC 6 ADJEI-DZIDE FRANKLIN ELENUJOR NOVA KING 0247928015 KPANDO, VOLTA EC/CEWP1/12/18/0025 DOMESTIC 7 ADOR AFEAFA 0246740864 SOGAKOPE EC/CEWP1/12/19/0018 DOMESTIC 8 ADZALI PAUL KOMLA 0245789340 TAFI MADOR EC/CEWP1/12/14/0054 DOMESTIC 9 ADZAMOA DIVINE MENSAH 0242769759 KRACHI EC/CEWP1/12/18/0031 DOMESTIC 10 ADZRAKU DODZI 0248682929 ALAVANYO EC/CEWP1/12/18/0033 DOMESTIC 11 AFADZINOO MIDAWO 0243650148 ANLO AFIADENYIGBA EC/CEWP1/06/14/0174 DOMESTIC 12 AFUTU BRIGHT 0245156375 HOHOE EC/CEWP1/12/18/0035 DOMESTIC 13 AGBALENYO CHRISTIAN KOFI 0285167920 ANLOKODZI, HO EC/CEWP1/12/13/0024 DOMESTIC 14 AGBAVE KINDNESS JERRY 0505231782 AKATSI, VOLTA REGION EC/CEWP1/12/15/0040 DOMESTIC 15 AGBAVOR SIMON 0243436475 KPANDO EC/CEWP1/12/16/0050 DOMESTIC 16 AGBAVOR VICTOR KWAKU 0244298648 AKATSI EC/CEWP1/06/14/0177 DOMESTIC 17 AGBEKO MICHEAL 0557912356 SOGAKOFE EC/CEWP1/06/19/0095 DOMESTIC 18 AGBEMADE SIMON 0244049157 DABALA, SOGAKOPE,VOLTA REGIONEC/CEWP1/12/16/0052 DOMESTIC 19 AGBEMAFLE MICHAEL 0248481385 HOHOE EC/CEWP1/12/18/0038 DOMESTIC 20 AGBENORKU KWAKU EMMANUEL 0506820579 DABALA JUNCTION- SOGAKOPE, VOLEC/CEWP1/12/17/0053 DOMESTIC 21 AGBENYEFIA SENANU FRANCIS 0244937008 CENTRAL TONGU EC/CEWP1/06/17/0046 DOMESTIC 22 AGBODOVI K. -

![Systèmes De Pensée En Afrique Noire, 9 | 1989, « Le Deuil Et Ses Rites I » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 16 Août 2012, Consulté Le 07 Août 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4744/syst%C3%A8mes-de-pens%C3%A9e-en-afrique-noire-9-1989-%C2%AB-le-deuil-et-ses-rites-i-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-16-ao%C3%BBt-2012-consult%C3%A9-le-07-ao%C3%BBt-2021-2094744.webp)

Systèmes De Pensée En Afrique Noire, 9 | 1989, « Le Deuil Et Ses Rites I » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 16 Août 2012, Consulté Le 07 Août 2021

Systèmes de pensée en Afrique noire 9 | 1989 Le deuil et ses rites I Danouta Liberski (dir.) Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/span/637 DOI : 10.4000/span.637 ISSN : 2268-1558 Éditeur École pratique des hautes études. Sciences humaines Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 novembre 1989 ISSN : 0294-7080 Référence électronique Danouta Liberski (dir.), Systèmes de pensée en Afrique noire, 9 | 1989, « Le deuil et ses rites I » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 16 août 2012, consulté le 07 août 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/span/ 637 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/span.637 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 7 août 2021. © École pratique des hautes études 1 Ce cahier se propose de revenir sur ce que S. Freud ou R. Hertz avaient conceptualisé sous l'expression "travail de deuil", en l'appliquant aux matériaux africains. Hertz proposait une mise en perspective des rites funéraires à partir de trois lieux d'interrogation simultanés: le traitement de la dépouille, celui de l'âme du mort et celui des survivants. Ici, nous prêtons en particulier attention à ce qui, dans les cérémonies funéraires, est montré d'une déconstruction progressive d e l'image du défunt, en tant que cette image appartient par toutes sortes de liens à la mémoire des vivants. NOTE DE LA RÉDACTION Le tirage de 610 exemplaires du numéro 9 est épuisé. La diffusion de ce tirage: 77 % en ventes, 10 % en échanges et 13 % à titre gratuit (dépôt légal, auteurs, etc.). Systèmes de pensée en Afrique noire, 9 | 1989 2 SOMMAIRE Présentation Danouta Liberski Le soupçon Christine Henry Les voies de la rupture : veuves et orphelins face aux tâches du deuil dans le rituel funéraire bobo (Burkina Faso) (première partie) Guy Le Moal Le mort circoncis.