Back.Pdf (274.4Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Album

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 Family Album Mary Elizabeth Bowen University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Bowen, Mary Elizabeth, "Family Album" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 909. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/909 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Family Album A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Mary Elizabeth (Missy) Bowen B.A., Grinnell College, 1981 May, 2009 © 2009, Mary Elizabeth (Missy) Bowen ii Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... -

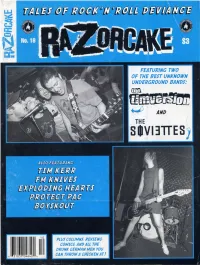

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #16 www.razorcake.com got up around 10am, after four hours of sleep. Someone falling After some Mexican food, and beer with fruit in it, Replay down the stairs woke me up. I skirted bodies littered in the front Dave, the really bendable bassist for Grabass Charlestons – who room and went for a glass of water. There was a small beer lake nights before, had landed into “a bed of the meanest cacti West II Texas has ever sprouted” then was arrested – chatted with me while on the kitchen floor. I grabbed the belt loops of the passed-out guy on the floor and scooched him out of the puddle. Wouldn't want I made some coffee. him to die in a quarter inch of beer. It was unfathomable that people “You forgot to ask some questions last night that were on your were still awake. I'd lasted until 6am. Some of the guys in the bands list,” he told me. The beer had gotten the better of my interviewing were shirtless, in the parking lot, and waving to the kids going to acumen. “Yeah, what'd I forget?” I asked. school. The bands I dig most tend to see touring as a vacation. “I never lived under an underpass. I lived under stairs until I I'll admit. I was a bit worried, until the sixth or seventh beer, got out of debt.” I'd found out that Dave, in a financial bind, that inviting thirteen plus people – Tiltwheel, The Tim Version, buckled down. -

Ex-Student Pleads Guilty to Charge of Conspiracy to Defraud University

Winner of four Guardian Student Media Awards Spring Term Week Three Wednesday 23 January 08 www.nouse.co.uk NOUSE Est. 1964 ‘When you see what’s going on in the world, you’ve got this rage. My therapy for that is to write songs.’ Manu Chao >>M9 Ex-student pleads guilty to charge of conspiracy to defraud University Askerov and accomplice admit attempt to cheat in exam Judge refuses to rule out possibility of prison sentences Henry James Foy included charges of acquir- guilty” to the charges read ing a University of York iden- against them. Askervov was NEWS EDITOR tification card with intent to impassive throughout the defraud the University. hearing while Drean was vis- A FORMER York student Drean, who previously ibly agitated. and his accomplice have held senior positions in the The case now proceeds pleaded guilty to one charge investment teams of Credit to a further hearing in the of conspiracy to defraud the Suisse and Bank of America, week beginning February 25, University, and will return to was also charged with two at which the judge will deliv- court next month facing counts of possessing crimi- er a pre-sentencing report. potential jail terms. nal assets totalling £20,000, Both defendants had their Judge Stephen believed to have been paid to bail extended until that date. Ashcroft, who presided over him by Askerov, who now Cameron requested that the hearing at York Crown lives in London. Drean Judge Ashcroft sentence the Court, said: “All sentences, pleaded not guilty to both of pair during the hearing, and including custody, will be these additional charges. -

A Year in the Life of Bottle the Curmudgeon What You Are About to Read Is the Book of the Blog of the Facebook Project I Started When My Dad Died in 2019

A Year in the Life of Bottle the Curmudgeon What you are about to read is the book of the blog of the Facebook project I started when my dad died in 2019. It also happens to be many more things: a diary, a commentary on contemporaneous events, a series of stories, lectures, and diatribes on politics, religion, art, business, philosophy, and pop culture, all in the mostly daily publishing of 365 essays, ostensibly about an album, but really just what spewed from my brain while listening to an album. I finished the last essay on June 19, 2020 and began putting it into book from. The hyperlinked but typo rich version of these essays is available at: https://albumsforeternity.blogspot.com/ Thank you for reading, I hope you find it enjoyable, possibly even entertaining. bottleofbeef.com exists, why not give it a visit? Have an album you want me to review? Want to give feedback or converse about something? Send your own wordy words to [email protected] , and I will most likely reply. Unless you’re being a jerk. © Bottle of Beef 2020, all rights reserved. Welcome to my record collection. This is a book about my love of listening to albums. It started off as a nightly perusal of my dad's record collection (which sadly became mine) on my personal Facebook page. Over the ensuing months it became quite an enjoyable process of simply ranting about what I think is a real art form, the album. It exists in three forms: nightly posts on Facebook, a chronologically maintained blog that is still ongoing (though less frequent), and now this book. -

![THE JERRY GRAY STORY – 1949 [Updated Jun 15, 2018 – Version JG.004E]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5040/the-jerry-gray-story-1949-updated-jun-15-2018-version-jg-004e-4975040.webp)

THE JERRY GRAY STORY – 1949 [Updated Jun 15, 2018 – Version JG.004E]

THE JERRY GRAY STORY – 1949 [Updated Jun 15, 2018 – Version JG.004e] January 3, 1949 [Monday]: Jerry Gray and his Orchestra – Bob Crosby’s Club 15 with The Andrews Sisters, 4:30–4:45 pm local time, CBS Columbia Square Playhouse, 6121 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, California. [Author’s Note: NYC/Eastern Standard Time UTC-5; Hollywood/Pacific Standard Time UTC-8.] The original CBS Network program was broadcast live to a good part of the country, airing at 7:30–7:45 pm in the East Coast [WCBS in New York City], 6:30–6:45 pm in the Central zone [WBBM in Chicago], and 4:30–4:45 pm on the West Coast [KNX in Los Angeles]. Club 15 – CBS Network Radio Broadcast, 1948-1949 Series, Episode 111: Details Unknown ____________________________________________________________________________________ January 4, 1949 [Tuesday]: Jerry Gray and his Orchestra – Bob Crosby’s Club 15 with Margaret Whiting and The Modernaires, 4:30–4:45 pm local time, CBS Columbia Square Playhouse, 6121 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, California. The original CBS Network program was broadcast live to a good part of the country, airing at 7:30–7:45 pm in the East Coast [WCBS in New York City], 6:30–6:45 pm in the Central zone [WBBM in Chicago], and 4:30–4:45 pm on the West Coast [KNX in Los Angeles]. Club 15 – CBS Network Radio Broadcast, 1948-1949 Series, Episode 112: Details Unknown ____________________________________________________________________________________ Part 4 - Page 1 of 230 January 5, 1949 [Wednesday]: Jerry Gray and his Orchestra – Bob Crosby’s Club 15 with The Andrews Sisters, 4:30–4:45 pm local time, CBS Columbia Square Playhouse, 6121 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, California. -

Mosaic USA Descriptions

Mosaic® USA Group and Type Descriptions Complete with “How to market” suggestions Contents Group and Type List ................................................................................................................................ 5 Group and Type Descriptions ................................................................................................................... 7 Group A: Power Elite .................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Type A01: American Royalty ................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Type A02: Platinum Prosperity .............................................................................................................................................................. 10 Type A03: Kids and Cabernet ................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Type A04: Picture Perfect Families ........................................................................................................................................................ 13 Type A05: Couples with Clout ............................................................................................................................................................... 14 Type A06: Jet Set Urbanites -

Summer 2006 V5

Newsletter for The Japan Exchange and Teaching Program Alumni Association, New York Chapter Vol. 15, Issue 3 SUMMER 2006 THE “WELCOME BACK” ISSUE What’s Inside?! NATSUKASHII IN NEW YORK 2 Letter from the Editor *Down Home Japan in NYC* 3 Comings & Goings by Steven Horowitz & Justin Tedaldi with lots of input from the JET Alum Community 4 JETAA Society Ever have a moment when you extensive a collection as need a good dose of Japan? some of the Japanese 5 What Are We Doing? places. JET alums discuss work Well, here's a guide to help you get your natsukashii on, broken For the wealthier and more 6 Bilingual Journalism down into categories to strike courageous, you can try Interview with Stacy Smith back against culture shock and seeking out one of the help you maintain (or at least “piano bars” tucked dis- 7Bai-bai New York! simulate) the Japan experience in cretely behind unassuming a way that brings it all back, even doors in Midtown East. by Alexei Esikoff if just for a moment. (They often have signs in Japanese saying “knock 3 7 Heeere’s Janak! DO YOU PLAY KARAOKE? times.”) These are hostess bars and generally by Clara Solomon Nothing brings back the fun (or painful) memories don't let in non-Japanese, but they skirt the like exercising your vocal chords with some lively legal issue by calling it a club and allowing 8 Softball Tournament Carpenters tunes or a nice heavy enka. While it’s entrance only to members. (Ed. note: Let us by Zack Ferguson hard to truly re-create the Japanese karaoke bar know if you get into one. -

The Journal of Kentucky Studies Volume Thirty-One 2014-2016 the Journal of Kentucky Studies

The Journal of Kentucky Studies Volume Thirty-one 2014-2016 Volume The Journal of Kentucky Studies Northern Kentucky University The Journal of Kentucky Studies Editor Gary Walton Northern Kentucky University Assistant Editor Donelle Dreese Northern Kentucky University Contributors The Journal welcomes articles on any theme—art, commentary, critical essays, history, literary criticism, short fiction, and poetry. Black and white photography is also accepted. Subject matter is not restricted to Kentucky. All manuscripts should follow the University of Chicago Manual of Style, be double-spaced, and be submitted in triplicate with S.A.S.E. Please include e-mail address. Also, please visit our website: https://kentuckystudiesjournal.wordpress.com The Journal is published yearly by the Northern Kentucky University Department of English. Statements of fact and opinion are made on the responsibility of the authors alone. All articles and other correspondence should be sent to: Northern Kentucky University, Gary Walton, Editor, The Journal of Kentucky Studies, Department of English, Nunn Drive, Highland Heights, Kentucky 41099. Phone (859) 572-5418. E-Mail: [email protected] Subscriptions Subscriptions are $20.00 per issue, pre-paid. Send checks or money orders to: Gary Walton, Editor, The Journal of Kentucky Studies, Department of English, Northern Kentucky University, Nunn Drive, Highland Heights, Kentucky 41099. Cover Photo Front cover photo: by Nelson Pilsner ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ Northern Kentucky University © 2016 Northern Kentucky University ISSN 8755-4208 This publication was prepared by Northern Kentucky University and printed with state funds (KRS 57.375). Northern Kentucky University is committed to building a diverse faculty and staff for employment and promotion to ensure the highest quality of workforce and to foster an environment that embraces the broad range of human diversity. -

![3^Rc^Ab) ?[PRTQ^B 2^\\^]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5388/3-rc-ab-prtq-b-2-9135388.webp)

3^Rc^Ab) ?[PRTQ^B 2^\\^]

M V B?824>3HBB4H)For a delicious adventure, make your own seasonings | Bch[Tb Concerts, movies, events, restaurants and more. XX435 1x1.75 A PUBLICATION OF | PLAN YOUR NIGHT AT WWW.EXPRESSNIGHTOUT.COM | O C T. 2 4 -26 , 20 08 | -- 5A44++ Weekend 3^Rc^ab) ?[PRTQ^b 2^\\^] Study: Half of U.S. doctors prescribe fake treatments COURTESY OF KARA TICHOC Mike Graham plays the Santa at Tysons Corner. ;>=3>=kAbout half of American doctors in Tysons near a new survey say they regularly give patients BP]cPBcPhb) placebo treatments — usually drugs or vita- deal to keep entertainer | ! mins that won’t really help their condition. And many of these doctors are not honest with their patients about what they are doing, ¼BPh0]hcWX]V½) McCain the survey found. That revs up attacks on Obama | # contradicts advice from 4C782BBCD3H the American Medical ?[PRTQ^bPQdbTS. Association, which rec- 679: The num- =Tf8\_a^eTS) ommends doctors use ber of doctors who treatments with the responded to the Rogers raises his full knowledge of their NIH study. More play upon return patients. than 1,200 were “It’s a disturbing find- asked to take part. from injury | $ ing,” said Franklin G. 62: The percent Miller, director of the of responding doc- 4=C4AC08=<4=C research ethics program tors who said the at the U.S. National use of placebos Institutes Health and was acceptable. one of the study authors. 1PQh6^]T) “There is an element of deception here which Angelina Jolie is contrary to the principle of informed con- sent.” The study was being published online searches for her in Friday’s issue of BMJ, formerly the British son in ‘Change- Medical Journal. -

Final Fantasy Mike Patton the Pipettes the Coup Dubstep

01 cover.qxd 26/05/2006 14:48 Page 1 park attack black lips alex smoke last.fm matmos the drips jana hunter final fantasy violins, videogames and a virtuoso nerdfox image • music • text mike patton the pipettes ‘It’s not a dark, disturbing, perverted record’ the coup issue 12 £3.30 dubstep 0 6 9 771744 243015 june/july 2006 ‘How does it feel to be style icons? Fan-bloody-tastic!’ 001-005 CONTENTSfmm ETREAD.qxd 23/05/2006 19:07 Page 2 Ray Davies - Other People’s Lives Josh Ritter - The Animal Years Isobel Campbell & Mark Lanegan “it’s never less than fascinating “His voice... boasts the same wry glow as early Jackson Browne, Ballad Of The Broken Seas and it’s frequently sublime” Mojo John Prine or James Taylor... - Uncut ‘An Instant Classic’ - NME (9/10) out now out now out now dEUS - Pocket Revolution Semifinalists Declan O’Rourke - Since Kyabram “A rare blend of the abstract NME “A series of hypnotically melancholy songs” WORD and the affecting” Mojo (4*) “One of the best debut records of 2006” out now out now 29TH MAY Duels - The Bright Lights... Rough Trade Shops Amusement Parks On Fire From the series of must have compilations lovingly Out Of The Angeles “Star Gazing Brilliance” NME put together by Rough Trade Shops A dizzying blast of psychedlic rock, inspired by the sonic 19th JUNE adventures of the Pixies, Sigur Ros & My Bloody Valentine. out now 5TH JULY Ron Sexsmith - Time Being Every Move A Picture Grandaddy - Just Like The Fambly Cat A masterclass in melody with effortless songwriting, this Heart = Weapon The fourth, final and most fabulous album from one of the Americas truly visionary bands.