Family Album

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KLOS March 17Th 2013

1 1 2 PLAYLIST MARCH 17TH 2013 9AM Good morning Apple Scruffs! George Harrison – Apple Scruffs - All Things Must Pass ‘70 2 3 This was a salute to the girls (and sometimes boys) who stood vigil at Apple, Abbey Road and anyplace a Fab was to likely to be. Upon recording the tune, George invited the “Apple Scruffs,” into the studio to have a listen. The Beatles – Sun King - Abbey Road Recorded w/ Mean Mr. Mustard as one song on July 24th 1969. Lennon in Playboy interview of 1980…”That’s a piece of garbage I had around”. Many parts of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon sound very much inspired by that piece of garbage. Lennon 1.00 The Beatles – Mean Mr. Mustard - Abbey Road Recorded July 24th. Written in India as we heard on the White LP demos from Esher. When the band is playing it during the Let It Be sessions Pam was then a Shirley. Lennon 1.00 The Beatles - Her Majesty – Abbey Road Recorded July 2, 1969. Originally fit between” Mean Mr. Mustard” and “Polythene Pam” McCartney 1.00 The Beatles – Polythene Pam - Abbey Road Recorded July 25th w/ “She Came in Through The Bathroom Window “. The only Beatles song inspired by a woman in New Jersey who dressed in polythene (but not jack boots or kilts). Written in India, demoed for the White LP. Lennon 1.00 The Beatles – She Came In Through The Bathroom Window - Abbey Road Recorded July 25th 1969. Written while in NYC to announce Apple. Based on a true story about some Scruffs breaking into Paul house at St. -

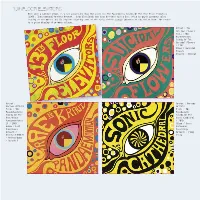

13Th FLOOR ELEVATORS

13th FLOOR ELEVATORS With such a seminal album, it’s not surprising that the cover for The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators (1966 : International Artists Artwork : John Cleveland) has been borrowed such a lot, often by psych upstarts (also leaning on the music) and CD compliers wanting some of the early sixties garage ambience to rub off on them. The result is a great display of primary colours. Artist : The Suicidal Flowers Title : The Psychedevilic Sounds Of The Suicidal Flowers / 1997 Album / Suicidal Flowers Artwork : Unknown Artist : Artist : Various Various Artists Artists Title : The Title : The Pseudoteutonic Psychedelic Sounds Of The Sounds Of The Prae-Kraut Sonic Cathedral Pandaemonium # / 2010 14 / 2003 Album / Sonic Album / Lost Cathedral Continence Recordings Artwork / Artwork : Jimmy Reinhard Gehlen Young - Andrea Duwa - Splash 1 COVERED! PAGE 6 1 LEONA ANDERSON ASH RA TEMPEL Leona Anderson’s 1958 long-player Music To Suffer By (Unique Records) This copy of Ash Ra Tempel’s 1973 album is a gem, though I must admit I’ve never been able to get vinyl albums Starring Rosi lovingly recreates Peter to shatter quite like that (or the Buzzcocks TV show intro). The Makers Geitner’s original (cover photo : Claus have actually copied the original image for their EP and then just Kranz). added a new label design. Artist : Magic Aum Gigi Title : Starring Keiko/ 2000? Album / Fractal Records Artwork : Peter Artist : The Geitner (Photo : Makers Magic Aum Gigi) Title : Music To Suffer By / 1995 3 track EP / Estrus Wreckers Artwork : Art Chantry Artist : Smiff-N- Artist : Pavement Wessum Title : Watery, Title : Dah Shinin’ Domestic / 1992 / 1995 EP / Matador Album / Wreck Records Records Artwork : Unknown Artwork : C.M.O.N. -

Music from a Darkened Room

DELTA GREEN-MUSIC FROM A DARKENED ROOM DENNIS DETWILLER Music from a Darkened Room A DELTA GREEN INVESTIGATION FOR 1 TO 4 AGENTS Wherein the Agents learn some threats are more tangible than others... BY DENNIS DETWILLER laces, like people, sometimes P go wrong. They turn off the The House on Spooner path and head into the shadows; Avenue becoming something other than Spooner Avenue is a quiet street normal. Black places filled with that can be set in any suburban BREAKDOWN OF INTEL blank rooms, closed doors and location in the United States. empty hallways lined with dust. 1206 Spooner Avenue is a small 1 THE HOUSE ON SPOONER AVENUE ! In these places your voice house, originally built in 1907, 2 THE AGENTS ARRIVE catches in your throat, the air and amended with additional 3 WHAT’S GOING ON AT 1206 SPOONER seems to hum and things hap- construction in the 1940’s. It’s not 4 TRAILS pen. People get hurt, objects van- pretty or ugly; it’s just plain. Few 4 1206 SPOONER — THE EXTERIOR ish. Bad feelings flow like the notice anything past the vibrant 4 INSIDE 1206 SPOONER loose tap in the bathroom and growth of ivy that scales the 4 THE COUNTY SEAT hate hangs in the air like old north side of the building. It is 8 SHUT DOORS, CLOSED SHADES paint. It smells of time and cir- wholly unremarkable in appear- 8 THE LUCKY FEW cumstance and something just a ance. But the neighbors are not 10 BREAK OUT THE BADGES little beyond the world. -

Bionicle: Journey's

BIONICLE: JOURNEY’S END Compiled for usage on Brickipedia © 2010 The LEGO Group. LEGO, the LEGO logo, and BIONICLE® are trademarks of the LEGO Group. All Rights Reserved. Over 100,000 years ago … Angonce walked purposefully toward a blank stone wall in the rear of his chamber. As the tall, spare figure approached, the blocks that made up the wall softened and shifted, forming an opening. He gazed out this new window at the mountains and forest below, sadness and regret in his dark eyes. He had often stood here before, reflecting upon the beauty of Spherus Magna. From the southern desert of Bara Magna to the great northern forest, it was a place of stunning vistas and infinite opportunities for knowledge. Angonce had spent most of his life discovering its mysteries, and had hoped for many more years in the pursuit. But now it seemed that was not to be. He had run every test that he could think of, and checked and rechecked his findings. They always came out the same: Spherus Magna was doomed. How did it come to this? Angonce wondered. How did we let it get so far? He, his brothers and sisters were scholars. Their theories, discoveries and inventions had transformed this world and changed the lives of the inhabitants, the Agori, in many ways. In gratitude, they had long ago been proclaimed rulers of Spherus Magna. The Agori called them the “Great Beings.” But the business of running a world – settling disputes, managing economies, dealing with defense issues, worrying about food and equipment supplies – all of this the Great Beings found a distraction. -

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

HISTORY of the TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST a Compilation

HISTORY OF THE TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST A Compilation Posting the Toiyabe National Forest Boundary, 1924 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Chronology ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Bridgeport and Carson Ranger District Centennial .................................................................... 126 Forest Histories ........................................................................................................................... 127 Toiyabe National Reserve: March 1, 1907 to Present ............................................................ 127 Toquima National Forest: April 15, 1907 – July 2, 1908 ....................................................... 128 Monitor National Forest: April 15, 1907 – July 2, 1908 ........................................................ 128 Vegas National Forest: December 12, 1907 – July 2, 1908 .................................................... 128 Mount Charleston Forest Reserve: November 5, 1906 – July 2, 1908 ................................... 128 Moapa National Forest: July 2, 1908 – 1915 .......................................................................... 128 Nevada National Forest: February 10, 1909 – August 9, 1957 .............................................. 128 Ruby Mountain Forest Reserve: March 3, 1908 – June 19, 1916 .......................................... -

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Living With Military-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) - A Hermeneutic Phenomenological Study by Rachel Kroch A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DIVISION OF APPLIED PSYCHOLOGY CALGARY, ALBERTA JUNE, 2009 © Rachel Kroch 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-54472-3 Our Hie Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-54472-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

An Original Album} an Honors Thesis (HONR 499} by Grant

The College Experience (An Original Album} An Honors Thesis (HONR 499} by Grant Armstrong Thesis Advisor Dr. Laurie Lindberg Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April2018 Expected Date of Graduation May 2018 Abstract Music has always been a way for people to express feelings and experiences. College is a major part of many people's lives, and everyone has a different experience. There are many situations, however, that a lot of college students experience. I created an album titled "The College Experience," consisting of three songs which I feel highlight some of the struggles and landmarks of college. The songs are "Undeclared," "Leftovers," and "What Have You Learned?" Each one describes a college student through a different experience in college. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Laurie Lindberg for advising me through this project. She provided much needed encouragement during times when I felt my songs weren't very good, and she kept me on track to help me finish on time. SrC-o/1 Under3rc,d The~.,.::-_, LD d. '-/(j;~ . Ll/ :J.-.0/lf' Process Analysis . r17G I first became interested in music when I was in middle school. The first instrument I learned to play was the drums. I took lessons for a few years and even played in my church's worship band for a while. Around this time, I began to play around on the piano, and I liked listening to songs and then figuring out how to play them. I even started writing original songs . The first song I ever wrote was for my brother when he went off to college. -

Universi^ Aaicronlms Intemationêd

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Billboard 1978-05-27

031ÿJÚcö7lliloi335U7d SPOTLIG B DALY 50 GRE.SG>=NT T HARTFJKJ CT UolOo 08120 NEWSPAPER i $1.95 A Billboard Publication The International Music -Record -Tape Newsweekly May 27, 1978 (U.S.) Japanese Production Tax Credit 13 N.Y. DEALERS HIT On Returns Fania In Court i In Strong Comeback 3y HARUHIKO FUKUHARA Stretched? TOKYO -March figures for By MILDRED HALL To Fight Piracy record and tape production in Japan WASHINGTON -The House NBC Opting underscore an accelerating pace of Ways and Means Committee has re- By AGUSTIN GURZA industry recovery after last year's ported out a bill to permit a record LOS ANGELES -In one of the die appointing results. manufacturer to exclude from tax- `AUDIO VIDISK' most militant actions taken by a Disks scored a 16% increase in able gross income the amount at- For TRAC 7 record label against the sale of pi- quantity and a 20% increase in value tributable to record returns made NOW EMERGES By DOUG HALL rated product at the retail level, over last year's March figures. And within 41/2 months after the close of By STEPHEN TRAIMAN Fania Records filed suit Wednesday NEW YORK -What has been tales exceeded those figures with a his taxable year. NEW YORK -Long anticipated, (17) in New York State Supreme held to be the radio industry's main 5S% quantity increase and a 39% Under present law, sellers of cer- is the the "audio videodisk" at point Court against 13 New York area re- hope against total dominance of rat- value increase, reports the Japan tain merchandise -recordings, pa- of test marketing. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian .