Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Six Sixty-Minute Mystery Plays

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2005 Six sixty-minute mystery plays Peter David Walther The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Walther, Peter David, "Six sixty-minute mystery plays" (2005). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3575. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3575 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature^ Date: T)ec- "Xo ^oST" Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explifcit consent. 8/98 Six Sixty-Minute Mystery Plays By Peter David Walther B.A. Carroll College, 1984 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana December 2005 Appro ve< 'hai rson Dean, Graduate School »Z- <5- Og Date UMI Number: EP34065 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. -

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

I L N O I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science University of Illinois Press 4 . $ 4 *. *"From the intriguing title to the final page, layers of cynical wit and care- ful choracter development occumulate achingfy in this beautfully rafted emotionally charged story" --Starred review, ScholLbary ornl *"Readers will take heart from the way Steve grows post his rebellion as they laugh at the plethora of comic situations and saply set up, welC executed punchllnes. "-Pointered review, Kirkus Reviews *"lt's Thomas's first novel and he has such an accurate voice that it screams read me now while I am hot and hot it is."-Starred review, VOYA 0689-80207.2 * $17.00 US/$23.O0 CAN (S&S BFYR) 0-689.80777-5 * $3.99 US/$4.99 CAN (Aladdin Ppoprboekst ALADDIN PAPERBACKS SIMON &f SCHUSTER BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS Imtprints of Simron &'P Schuster Children's Publishing· Division 1230 Avenue of the Americas * New Yorkr, NV 10020 THE B UL LE T IN OF THE CENTER FOR CHILDREN'S BOOKS September 1996 Vol. 50 No. 1 A LOOK INSIDE 3 THE BIG PICTURE American Fairy Tales: From Rip Van Winkle to the Rootabaga Stories comp. by Neil Philip; illustrated by Michael McCurdy 5 NEW BOOKS FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE Reviewed titles include: 5 * The Story ofLittle Babaji by Helen Bannerman; illus. by Fred Marcellino 11 * The Abracadabra Kid by Sid Fleischman 16 * How to Make Holiday Pop-Ups by Joan Irvine; illus. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Song-Book.Pdf

1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Rockin’ Tunes Ain’t No Mountain High Enough 6 Sherman The Worm 32 Alice The Camel 7 Silly Billy 32 Apples And Bananas 7 Swimming, Swimming 32 Baby Jaws 8 Swing On A Star 33 Bananas, Coconuts & Grapes 8 Take Me Out To The Ball Game 33 Bananas Unite 8 The Ants Go Marching 34 Black Socks 8 The Bare Necessities 35 Best Day Of My Life 9 The Bear Song 36 Boom Chicka Boom 10 The Boogaloo 36 Button Factory 11 The Cat Came Back 37 Can’t Buy Me Love 11 The Hockey Song 38 Day O 12 The Moose Song 39 Down By The Bay 12 The Twinkie Song 39 Don’t Stop Believing 13 The Walkin’ Song 39 Fight Song 14 There’s A Hole In My Bucket 40 Firework 15 Three Bears 41 Forty Years On An Iceberg 16 Three Little Kittens 41 Green Grass Grows All Around 16 Through The Woods 42 Hakuna Matata 17 Tomorrow 43 Here Little Fishy 18 When The Red, Red Robin 43 Herman The Worm 18 Yeah Toast! 44 Humpty Dump 19 I Want It That Way 19 If I Had A Hammer 20 Campfire Classics If You Want To Be A Penguin 20 Is Everybody Happy? 21 A Whole New World 46 J. J. Jingleheimer Schmidt 21 Ahead By A Century 47 Joy To The World 21 Better Together 48 La Bamba/Twist And Shout 22 Blackbird 49 Let It Go 23 Blowin’ In The Wind 50 Mama Don’t Allow 24 Brown Eyed Girl 51 M.I.L.K. -

Family Album

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 Family Album Mary Elizabeth Bowen University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Bowen, Mary Elizabeth, "Family Album" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 909. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/909 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Family Album A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Mary Elizabeth (Missy) Bowen B.A., Grinnell College, 1981 May, 2009 © 2009, Mary Elizabeth (Missy) Bowen ii Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Representations of Teenage Protagonists in Bestselling YA Fiction

Actors and Aliens: Representations of Teenage Protagonists in Bestselling YA Fiction by Rebecca Ball A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2016 Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 Literature Overview 12 Actors and Aliens 22 I. Actors 23 II. Aliens 30 III. Dramatic strategies 38 IV. Instinct over strategy 52 V. Consequences 61 The In-School Study 75 I. Questionnaire findings 78 II. Interview findings 84 III. Discussion 95 Conclusion 101 Works Cited 111 Appendix 117 i Acknowledgements I would like to extend my sincere thanks to my supervisors – Drs Geoff Miles, Charles Ferrall and Gillian Hubbard at the Victoria University of Wellington – for their guidance and support throughout the at times uncharted territory of this project. I would like to acknowledge them, and the rest of the English Department at Victoria University, for their positivity about and understanding of working alongside an MA student with a baby. I would like to thank Suze Randal for her expert support on matters of data processing and proof-reading. I am immensely thankful to Steve Langley for his ongoing help and encouragement. I am also very grateful to all those scholars whose work has helped shape my thesis, and to the people who allowed me to interview and quote them in my paper: Anna Hart at Nielsen, Len Vlahos at BISG, Lisa Davis at Hachette, and Booksellers NZ. My special thanks, too, go to the high-school staff and students who helped me with the in-school study – their generosity and insights allowed me to produce a truly original contribution to the YA discussion. -

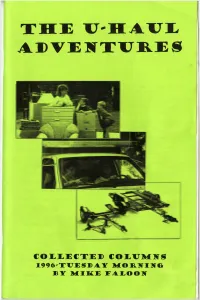

A D V E N T U R

THE U'HAUL ADVENTURES COLLECTED COLUMNS 1996 TUESDAY MOR N I NG BY MIKE FALOON W riter Mike Faloon Presents The Choose an Intro S weepstakes ! Greetings, reader. I’ll be damned if I can decide which introduction to use for the The U- Haul Adventures, so I’ll leave the choice to you. Simply select your favorite intro, and inform me of your choice via mail or email. I’ll tally the votes and the most popular introduction will be the one that everyone reads! Tally ho! Mike #1 - For those who like the literary approach: “A prologue is written last but placed first to explain the book's shortcomings and to ask the reader to be kind. But a prologue is also a note of farewell from a writer to his book. For years the writer and his book have been together—friends or bitter enemies but very close as only love and fighting can accomplish. ” —John Steinbeck, Journal o f a Novel #2 - For those who dig the dry details: The U-Haul Adventures could be accurately subtitled “Columns I Wrote for Other Zines That My Friends Never Got to Read, Along with New Stuff I Wrote for Tour.” Last summer I went through the box in which I keep copies of zines I’ve written for. Flipping through the stack I realized that most of my friends never had a chance to read the columns, and never would given that all but one of the zines is now extinct. (Josh Rutledge’s fab Now Wave being the noteworthy exception.) And that’s not right because I often write with my friends in mind. -

National Future Farmer Owned and Published by the Future Farmers of America

The National Future Farmer Owned and Published by the Future Farmers of America /..;»> , \ ^ \ "Did ya hear? He's buying it. Just the one I hoped we'd get." Remember the first time you went with your Dad to Have you noticed more Big Orange Tractors these buy a tractor? These youngsters are getting a lesson days? You should, because they're moving onto farms in buying that's good for them. Many of you are in ever-increasing numbers. Reasons? Many. Allis- ah'eady making your own buying decisions. And there Chalmers dealers are long-time supporters of F.F.A. are few things that can make anyone think harder They'd really like to talk with you about any of the than making a major purchase with his own money. long line . D-10 to Big D-21. ALLIS-CHALMERS .THE TRACTOR PEOPLE • MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN Wiit you know what to look for when huyinfi your first eiBr? Buying a ust-d car? Learn to read the signs — the tires, the sheet metal, the upholstery. They can tell you much ahout how the car was driven and about its gt'iieral condition. You'll end up getting more car for your money, making your first car an even bigger pleasure than you'd hoped. Look at the car from all angles and under the hood. How about the brake pedal? Does it offer firm Do you see any welds? How ahout the rocker panels'."* resistance after you press it down an inch or two? Any evidence of filler nietaly Find out how hadly If it doesn't there could he a leak in the system — the car was damaged. -

Augsome Karaoke Song List Page 1

AUGSome Karaoke Song List 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 112 - Come See Me 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only You 112 - Peaches And Cream 112 - U Already Know 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Amber 311 - Beyond The Gray Sky 311 - Creatures (For A While) 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - Down 311 - First Straw 311 - Hey You 311 - I'll Be Here Awhile 311 - Love Song 311 - You Wouldn't Believe 411 - Dumb 411 - On My Knees 411 - Teardrops 702 - Get It Together 702 - I Still Love You 702 - Steelo 702 - Where My Girls At 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More, A 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 1927 - That's When I Think Of You 1975 - Chocolate 1975 - City 1975 - Love Me 1975 - Robbers 1975 - Sex 1975 - Sound 1975 - Ugh 1 Giant Leap And Jazz Maxi - My Culture 10 Years - Beautiful 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs - Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping Page 1 AUGSome Karaoke Song List 101 Dalmations - Cruella de Vil 10Cc - Donna 10Cc - Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc - I'm Mandy 10Cc - I'm Not In Love 10Cc - Rubber Bullets 10Cc - Things We Do For Love, The 10Cc - Wall Street Shuffle 112 And Ludacris - Hot And Wet 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 12 Stones - Crash 12 Stones - We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co.