The Israel Policy Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

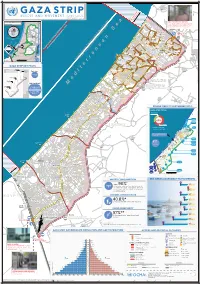

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

War Crimes Prosecution Watch, Vol. 13, Issue 24

PILPG Logo Case School of Law Logo War Crimes Prosecution Watch Editor-in-Chief Taylor Frank FREDERICK K. COX Volume 13 - Issue 24 INTERNATIONAL LAW CENTER January 7, 2019 Technical Editor-in-Chief Ashley Mulryan Founder/Advisor Michael P. Scharf Managing Editors Sarah Lucey Lynsey Rosales War Crimes Prosecution Watch is a bi-weekly e-newsletter that compiles official documents and articles from major news sources detailing and analyzing salient issues pertaining to the investigation and prosecution of war crimes throughout the world. To subscribe, please email [email protected] and type "subscribe" in the subject line. Opinions expressed in the articles herein represent the views of their authors and are not necessarily those of the War Crimes Prosecution Watch staff, the Case Western Reserve University School of Law or Public International Law & Policy Group. Contents AFRICA CENTRAL AFRICA Central African Republic PSG footballer linked to war crimes and global fraudster (EU Anti-Corruption) French court orders sending Central African Republic war crimes suspect to ICC (Reuters) Sudan & South Sudan Janjaweed, ghost squads and a divided nation: How Sudan's Bashir stays in power (CNN) UN calls on Sudan to probe killing of protesters (Sudan Tribune) Sudanese opposition groups issue declaration for regime change (Sudan Tribune) Democratic Republic of the Congo Risk of 'grave crimes' in DRC ahead of vote (News24) EU condemns expulsion of envoy Bart Ouvry (BBC) DRC electoral fraud fears rise as internet shutdown continues (The Guardian) -

Shelter 2014 A3 V1 Majed.Pdf (English)

GAZA STRIP: Geographic distribution of shelters 21 July 2014 ¥ 3km buffer Zikim a 162km2 (44% of GaKazrmaiya area) 100,000 poeple internally displaced e Estimated pop. of 300,000 B?4 84,000 taking shelter in UNRWA schools S Yad Mordekhai n F As-Siafa B?4 B?34 Governorate # of IDPs a ID y d e e e h b s a R Netiv ha-Asara Gaza 3 2,401 l- n d A e a c Erez Crossing KhanYunis 9 ,900 r Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) r (Umm An-Naser) fo 4 º» r h ¹ a n 1 al n Middle 7 ,200 S ee 0 l-D e E 2 E t Beit Lahiya 'Izbat Beit Hanoun a t i k k y E a e l- j S North 2 1,986 l B lo l- i a a A m h F a - 34 i u r l B? J A 5! 5! 5! d L t 'Arab Maslakh Madinat al 'Awda i S w Rafah 1 2,717 ta 5! Beit Lahiya r af 5! ! ee g 5! S 5 az Ash Shati' Camp l- 5! W Beit Hanoun e A !5! Al- n 5!5! 5 lil 5!5! Al-q ka ha i uds ek K 5! l-S Grand Total 8 4,204 M h 5!Jabalia A s 5!5! Jabalia Camp i 5!5! D S !x 5!5!5! a a r le a d h Source of data: UNRWA F o m n a 5!5! a r a K J l- a E m l a a l A n b 5! a 5!de Q 5! l l- d N A Gaza e as e e h r s City a R l- A 5!5! 5! 5! s d ! Mefalsim u 5! Q ! 5! l- 5 A 5! A l- M o n a t 232 kk a B? e r l-S A Kfar Aza d a o R l ta s a o C Sa'ad Al Mughraqa arim Nitz ni - (Abu Middein) Kar ka ek n ú S ú 5! e b l- B a A r tt Juhor ad Dik a a m h K O l- ú A ú Alumim An Nuseirat Shuva Camp 5! 5! Zimrat B?25 5! 5! 5! I S R A E L n e e 5! Kfar Maimon D a 5! - k Tushiya l k Al Bureij Camp E e Az Zawayda h S la l- a A S 5! Be'eri !x 5! Deir al Balah Al Maghazi Shokeda Camp 5! 5! Deir al Balah 5!5! Camp Al Musaddar d a o f R la k l a o ta h o 232 -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Chabad Rabbanim” Has Settlements in the Sharon Together Expanded Over the Years

@LKQBKQP OUR PORTION, OUR LOT, OUR HERITAGE D’var Malchus THREE MIRACLE STORIES Stories | Nosson Avrohom REBBI GAVE HONOR TO THE WEALTHY [CONT.] Insight | Yisroel Yehuda A REBBE: PIETY, EDUCATION, AND FIERY DEVOTION Yechidus USA I SAID ‘NO WAY’ TO THE TIBETAN 744 Eastern Parkway Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409 MASTER Tel: (718) 778-8000 Profile | Nosson Avrohom Fax: (718) 778-0800 [email protected] www.beismoshiach.org WHAT DO THE PROFESSORS SAY? EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: [CONT.] M.M. Hendel Science & Geula | Prof. Shimon Silman ENGLISH EDITOR: Boruch Merkur THE TRACTOR CONTINUES TO ROLL [email protected] Shleimus HaAretz | Shai Gefen HEBREW EDITOR: Rabbi Sholom Yaakov Chazan [email protected] Beis Moshiach (USPS 012-542) ISSN 1082- SO FAR YET SO CLOSE 0272 is published weekly, except Jewish Shlichus | Rabbi Yaakov Shmuelevitz holidays (only once in April and October) for $140.00 in the USA and in all other places for $150.00 per year (45 issues), by Beis Moshiach, 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Periodicals postage paid at FUNDRAISING IN THE ERA OF Brooklyn, NY and additional offices. Postmaster: send address changes to Beis MOSHIACH [CONT.] Moshiach 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, Shlichus | Raanan Isserof NY 11213-3409. Copyright 2008 by Beis Moshiach, Inc. Beis Moshiach is not responsible for the A CHABAD RAV, NO ‘ORDINARY’ RAV content of the advertisements. Insight | Interview by Nosson Avrohom A¤S>OJJ>I@ERP OUR PORTION, OUR LOT, OUR HERITAGE Translated and adapted by Dovid Yisroel Ber Kaufmann This week’s Torah reading The mitzva of inheritance is listed last contains the laws of inheritance. -

![Income Tax Ordinance [New Version] 5721-1961](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4190/income-tax-ordinance-new-version-5721-1961-2334190.webp)

Income Tax Ordinance [New Version] 5721-1961

Disclaimer : The Following is an unofficial translation, and not necessarily an updated one. The binding version is the official Hebrew text. Readers are consequently advised to consult qualified professional counsel before making any decision in connection with the enactment, which is here presented in translation for their general information only. INCOME TAX ORDINANCE [NEW VERSION] 5721-1961 PART ONE – INTERPRETATION Definitions 1. In this Ordinance – "person" – includes a company and a body of persons, as defined in this section; "house property", in an urban area – within its meaning in the Urban Property Ordinance 1940; "Exchange" – a securities exchange, to which a license was given under section 45 of the Securities Law, or a securities exchange abroad, which was approved by whoever is entitled to approve it under the statutes of the State where it functions, and also an organized market – in Israel or abroad – except when there is an explicitly different provision; "spouse" – a married person who lives and manages a joint household with the person to whom he is married; "registered spouse" – a spouse designated or selected under section 64B; "industrial building ", in an area that is not urban – within its meaning in the Rural Property Tax Ordinance 1942; "retirement age" – the retirement age, within its meaning in the Retirement Age Law 5764-2004; "income" – a person's total income from the sources specified in sections 2 and together with amounts in respect of which any statute provides that they be treated as income for purposes -

©2015 Assaf Harel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2015 Assaf Harel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THE ETERNAL NATION DOES NOT FEAR A LONG ROAD”: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF JEWISH SETTLERS IN ISRAEL/PALESTINE By ASSAF HAREL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Anthropology Written under the direction of Daniel M. Goldstein And approved by ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “The Eternal Nation Does Not Fear A Long Road”: An Ethnography Of Jewish Settlers In Israel/Palestine By ASSAF HAREL Dissertation Director: Daniel M. Goldstein This is an ethnography of Jewish settlers in Israel/Palestine. Studies of religiously motivated settlers in the occupied territories indicate the intricate ties between settlement practices and a Jewish theology about the advent of redemption. This messianic theology binds future redemption with the maintenance of a physical union between Jews and the “Land of Israel.” However, among settlers themselves, the dominance of this messianic theology has been undermined by postmodernity and most notably by a series of Israeli territorial withdrawals that have contradicted the promise of redemption. These days, the religiously motivated settler population is divided among theological and ideological lines that pertain, among others issues, to the meaning of redemption and its relation to the state of Israel. ii This dissertation begins with an investigation of the impact of the 2005 Israeli unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip upon settlers and proceeds to compare three groups of religiously motivated settlers in the West Bank: an elite Religious Zionist settlement, settlers who engage in peacemaking activities with Palestinians, and settlers who act violently against Palestinians. -

¹¹º» North Gaza Beit Lahia Al Salateen Al Jam'ia Hatabiyya JK Wastewater Al Kur'a Treatment Plant El Khamsa Salahas Ed Sultan Deen Abedl Hamaid

Beit Shikma Ge'a United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim GAZA STRIP Karmiya Scan it! Navigate! ACCESS AND CLOSURE with QR reader App with Avenza PDF Maps A App DECEMBER 2012 Yad Mordekhai ¥ 4 B?34 As-Siafa B? No FishingA Zone 1.5 nautical miles EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) Ar Rasheed Open six days (daytime) a week for the movement of international workers and limited number of authorized PalestiniansNetiv including ha-Asara medical, humanitarian cases and aid workers. Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Ghaboon Hai Al Amal Fado's B?4 Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) P! ¹¹º» North Gaza Beit Lahia Al Salateen Al Jam'ia Hatabiyya JK Wastewater Al Kur'a Treatment Plant El Khamsa SalahAs Ed Sultan Deen Abedl Hamaid D D D D DD D D D D D Beit Lahiya D D J" D D D D D D D D D D Aslan D D D D Al-Sekka D D D D D D D D Al Mathaf D D D D D D P! D D Abu Rahma D D D D D D D D Hotel D D " D D . D D 'Izbat Beit Hanoun D D D D Alkhazan Beit Lahia Main St. D D D D D D D D Ar Rasheed D D Arc-Med El-Bahar D D D D D D Al-SekkaAl Balad D D D D Al Share' El Am D D 34 D D Hotel D D B? Al-Faloja D D ." D D D WXY D D Sheikh Zayed D D !P Hai Al Amal D D Al Mashroo D D Madinat al 'Awda D D D Housing Project Beit Hanoun D D D D D D D D Beit Hanoun D D D D Jabalia Camp v® D D Al-Zatoon D D nm Industrial J" D D D D D ® D v D D Zone nm D D D D D D Beit Hanoun D D P! D D Al Masreen D D D D D D Kamal Edwan D D D D D D Al-Saftawi St Hospital D D P! D D D D Khalil Al-Wazeer D D Hospital D Ash -

Israeli Land Grab and Forced Population Transfer of Palestinians: a Handbook for Vulnerable Individuals and Communities

ISRAELI LAND GRAB AND ISRAELI LAND GRAB AND FORCED POPULATION TRANSFORCEDFER OF PALEST POINPIANSULAT: ION TRANSFERA Handbook OF PALEST for INIANS Vulnerable Individuals and Communities A Handbook for Vulnerable Individuals and Communities BADIL بديــل Resource Center املركز الفلسطيني for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights ملصـادر حقـوق املواطنـة والﻻجئـيـن Bethlehem, Palestine June 2013 BADIL بديــل Resource Center املركز الفلسطيني for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights ملصـادر حقـوق املواطنـة والﻻجئـيـن Researchers: Amjad Alqasis and Nidal al Azza Research Team: Thayer Hastings, Manar Makhoul, Brona Higgins and Amaia Elorza Field Research Team: Wassim Ghantous, Halimeh Khatib, Dr. Bassam Abu Hashish and Ala’ Hilu Design and Layout: Atallah Salem Printing: Al-Ayyam Printing, Press, Publishing & Distribution Company 152 p. 24cm ISBN 978-9950-339-39-5 ISRAELI LAND GRAB AND FORCED POPULATION TRANSFER OF PALESTINIANS: A HANDBOOK FOR VULNERABLE INDIVIDUALS AND COMMUNITIES / 1. Palestine 2. Israel 3. Forced Population Transfer 4. Land Confiscation 5. Restrictions on Use and Access of Land 6. Home Demolitions 7. Building Permits 8. Colonization 9. Occupied Palestinian Territory 10. Israeli Laws DS127.96.S4I87 2013 All rights reserved © BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights June 2013 Credit and Notations Many thanks to all interview partners who provided the foundation for this publication, in particular to Suhad Bishara, Nasrat Dakwar, Manal Hazzan-Abu Sinni, Quamar Mishirqi, Ekram Nicola and Mohammad Abu Remaileh for their insightful and essential guidance in putting together this handbook. We would also like to thank Gerry Liston for his contribution in providing the legal overview presented in the introduction and Rich Wiles for his assistance throughout the editing phase. -

Gaza A0 2014 23July.Pdf

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim GAZA EMERGENCY Karmiya e s n e o il ACCESS RESTRICTIONS Z m A g l in a Yad Mordekhai h c s ti ¥ i u F a 4 ?B34 JULY 2014 As-Siafa ?B nA d o e e N 5 h . s 1 a EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) R r OPEN, six days (daytime) a week for the movement A Gaza emergency of international workers and limited number of Occupied Palestinian Territory: authorizedNetiv Palestiniansha-Asara including aid workers, medical, humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Humanitarian Snapshot (as of 22 July 2014) Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Situation Overview Ghaboon Hai Al Amal Geographic breakdown of fatilities 1.8 As the Gaza emergency enters its third week and the Israeli Fado's ?B4 Al Qaraya al Badawiya (8 to 22 July) million ground offensive continues for the fifth consecutive day, the (Umm An-Naser) affected people in casualty toll among Palestinian civilians continues to escalate. !P ¹º» The increase in the targeting of homes and killing of multiple ¹ the Gaza Strip members of the same families is of increasing concern. Intense n North Gaza ee Erez Beit Lahia D overcrowding in shelters, compounded by the lack of access to d ¹ Al Salateen K Wastewater E Beit Lahiya some of them, has undermined the living conditions of IDPs, as Al Jam'ia Hatabiyya J h ! Al Kur'a Treatment Plant la mass displacement continues. El Khamsa Sa As Sultan ! Beit Lahiya Abedl Hamaid D D D D D ! D D D Jabalya Beit "J D n Sea D D 93 D D D D 33 d D D D D D D The killing of multiple members of the same families as a result e D D Aslan D D Hanoun e Al-Sekka D D D D D D D D h D D D D Al Mathaf !P D D nea s D D of the targeting of homes became increasingly frequent in the D D a Abu Rahma D D D D ! a a D D " k D D a Gaza City . -

2021 Humanitarian Needs Overview

WORKING DOCUMENT WORKING DOCUMENT HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2021 NEEDS OVERVIEW ISSUED DECEMBER 2020 OPT 1 HUMANITARIAN NEEDS OVERVIEW 2021 About Get the latest updates This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the OCHA coordinates humanitarian action to ensure crisis-affected people receive the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. It provides a shared assistance and protection they need. It understanding of the crisis, including the most pressing works to overcome obstacles that impede humanitarian need and the estimated number of people who humanitarian assistance from reaching people affected by crises, and provides leadership in need assistance. It represents a consolidated evidence base and mobilizing assistance and resources on behalf helps inform joint strategic response planning. The designations of the humanitarian system. employed and the presentation of material in the report do not www.ochaopt.org imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part twitter.com/ochaopt of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries PHOTO ON COVER Humanitarian Response aims to be the central Reem, 9th grade, Bethlehem Governorate. © 2020 website for Information Management tools Photo: Save the Children/Jonathan Hyams. and services, enabling information exchange between clusters and IASC members operating within a protracted or sudden onset GENERAL DISCLAIMER: crisis. Unless otherwise indicated, data in this document is valid as of end September 2020. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/ operations/occupied-palestinian-territory Humanitarian InSight supports decision- makers by giving them access to key humanitarian data.