A Survey of Shakespearean Performances in Japan from 2001-2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Japanese Shakespeare Productions in 2014-15

Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance vol. 14 (29), 2016; DOI: 10.1515/mstap-2016-0013 ∗ Shoichiro Kawai Some Japanese Shakespeare Productions in 2014-15 Abstract: This essay focuses on some Shakespeare productions in Japan during 2014 and 2015. One is a Bunraku version of Falstaff, for which the writer himself wrote the script. It is an amalgamation of scenes from The Merry Wives of Windsor and those from Henry IV. It was highly reputed and its stage design was awarded a 2014 Yomiuri Theatre Award. Another is a production of Much Ado about Nothing produced by the writer himself in a theatre-in-the-round in his new translation. Another is a production of Macbeth arranged and directed by Mansai Nomura the Kyogen performer. All the characters besides Macbeth and Lady Macbeth were performed by the three witches, suggesting that the whole illusion was produced by the witches. It was highly acclaimed worldwide. Another is a production of Hamlet directed by Yukio Ninagawa, with Tatsuya Fujiwara in the title role. It was brought to the Barbican theatre. There were also many other Shakespeare productions to commemorate the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth. Keywords: Shakespeare, adaptation, Bunraku, Kyogen, Falstaff, Much Ado about Nothing, Macbeth, Hamlet, Japanese traditional theatre, Yukio Ninagawa Bunraku Falstaff In the year 2014, there were many Shakespearean productions in Japan to commemorate the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth. Among them was a Bunraku (Japanese traditional puppet theatre) version of Falstaff, for which I wrote the playscript in the pseudo-classical, rhythmical Japanese called gidayu-bushi. -

Japanese Film Festival 2013 Flyer Here

3 MARCH 201 FREE ADMISSION JAPANESE NO BOOKINGS FILM 日本映画祭 VENUE: Cinema 4, Hoyts Northlands Northlands Shopping Centre, Main North Road ENQUIRIES Consular Office of Japan (03) 366-5680 FESTIVAL [email protected] ©2010 GNDHDDTW ©「時をかける少女製作委員会」2006 Monday 4 March 6.30 pm Tuesday 5 March 6.30 pm Wednesday 6 March 6.30pm 借りぐらしのアリエッテイ 時をかける少女 まあだだよ THE SECRET THE GIRL WHO LEAPT WORLD OF ARRIETTY THROUGH TIME MAADADAYO G 2010 94 minutes PG 2006 126 minutes PG 1993 134 minutes Director: Hiromasa Yonebayashi Director: Mamoru Hosoda Director: Akira Kurosawa Main Cast Voices: Mirai Shida (Arrietty), Main Cast Voices:Riisa Naka (Makoto Cast:Tatsuo Matsumura, Kyoko Kagawa, Ryunosuke Kamiki (Sho), Tomokazu Miura Konno), Takuya Ishida (Chiaki Mamiya), Hisashi Igawa, Joji Tokoro, Masayuki Yui, (Pod), Shinobu Otake (Homily) Mitsutaka Itakura (Kousuke Tsuda) Akira Terao Music by Cécile Corbel Music by Kiyoshi Yoshida Timeless and endearing! Luminous animation and a captivating Intriguing and heartwarming! story that will remain with you! Retired Professor Hyakken Uchida is the A Studio Ghibli animation based on Mary An animation of Yasutaka Tsutsui’s epitome of the Japanese “Sensei” (teacher) Norton’s novel “The Borrowers” about a novel of the same name, centered on 3 – respected and admired by his tiny girl, Arrietty, who lives secretly with teenage friends, Makoto, Chiaki and ex-students, who celebrate his birthday her parents beneath a grand house with a Kousuke. After a car accident Makoto annually. Akira Kurosawa’s 30th and final large garden. One summer day Arrietty is obtains the power to time travel and film wisely portrays the mutual benefits discovered by Sho, a 12-year-old boy who believes she can use it to her advantage, of the relationship between an elderly has come to live in the house. -

Aikido XXXIX

Anno XXXIX(gennaio 2008) Ente Morale D.P.R. 526 del 08/07/1978 Periodico dell’Aikikai d’Italia Associazione di Cultura Tradizionale Giapponese Via Appia Nuova 37 - 00183 Roma ASSOCIAZIONE DI CULTURA TRADIZIONALE GIAPPONESE AIKIKAI D’ITALIA 30 ANNI DI ENTE2008 MORALE 3NOVEMBRE0 Sommario 02 - Editoriale 03 - Comunicati del fondo Hosokawa 04 - Nava, estate 2007... 05 - Ricordi:Giorgio Veneri - Cesare Abis 07 - ..a proposito di Ente Morale 10 - Lezione agli insegnanti dell’Aikikai d’Italia del maestro Hiroshi Tada Composizione dell’Aikikai d’Italia 14 - Le due vie del Budo: Shingaku no michi e Shinpo no michi Presidente 15 - Premessa allo studio dei principi Franco Zoppi - Dojo Nippon La Spezia di base di aikido 23 - La Spezia, Luglio 2007 Vice Presidente 25 - Roma, Novembre 2007 Marino Genovesi - Dojo Fujiyama Pietrasanta 26 - I giardini del Maestro Tada Consiglieri 28 - Nihonshoki Piergiorgio Cocco - Dojo Musubi No Kai Cagliari 29 - Come trasformarsi in un enorme macigno Roberto Foglietta - Aikido Dojo Pesaro Michele Frizzera - Dojo Aikikai Verona 38 - Jikishinkage ryu kenjutsu Cesare Marulli - Dojo Nozomi Roma 39 - Jikishinkageryu: Maestro Terayama Katsujo Alessandro Pistorello - Aikikai Milano 40 - Nuove frontiere: il cinema giapponese Direttore Didattico 52 - Cinema: Harakiri Hiroshi Tada 55 - Cinema: Tatsuya Nakadai Vice Direttori Didattici 58 - Convegno a Salerno “Samurai del terzo millennio” Yoji Fujimoto Hideki Hosokawa 59 - Salute: Qi gong Direzione Didattica 61 - Salute: Tai ji quan- Wu Shu - Aikido Pasquale Aiello - Dojo Jikishinkai -

The Inventory Ofthe Donald Richie Collection

The Inventory ofthe Donald Richie Collection #1134 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Richie, Donald, 1924- April 1994 #77A Box 1 I. MANUSCRIPT A. THE JAPAN JOURNALS. 1947-1994. Leza Lowitz editor. Photocopy of typescript. Finished Draft dated March, 1994. 411 p. Vol I. pp. 1-195, (#1) Vol I I . pp. 19 6-411, ( # 2) ., Richie, Donald Preliminary Listing 2/25/97; 2/26/97 Box2 I. Manuscripts A. Unpublished novels by DR 1. HATE ALL THE WORLD, 1944, t.s. with holograph editing, 300 p., unbound 2. AND WAS LOST, AND IS FOUND, 1949, t.s. with holograph editing, 3rd draft, 60 p., bound 3. THE WAY OF DARKNESS, 1952, carbon t.s. with holograph editing, 250 p., bound, includes newspaper tearsheets 4. MAN ON FIRE, 1963, carbon t.s. with holograph editing, 265 p, bound 5. THE DROWNED, 1983 1. T.s., 108 p. 2. T.s., p/c, with holograph editing, 108 p.; includes notes from "Dick" 6. "The Inland Sea," screenplay, 1993; t.s., 2 copies, one with holograph editing; includes correspondence and related materials II. Play/Ballet Material A. "Edward II" by Christopher Marlowe, 1968 1. Acting version for Troupe Hana, bound; t.s. stage directions with pasted dialogue lines; includes b/w photographs 2. Envelope containing "Edward II" material in Japanese 3. Eight contact sheets, Nov. 1968 B. "An Evening of Four Verse Plays," 1975 1. Director's copy script, halft.s., half pasted in 2. Related materials--posters, pamphlets, photos C. Collection of ballet publicity material-- l 980's previous box: SB 18B Richie, Donald Preliminary Listing 5/21/97 Box2 I. -

学生の方は当日券が500円でご購入いただけます。 Advance Tickets Go on Sale from Saturday October 8 Via Ticket PIA and Lawson Ticket! Same Day Tickets Available to Students for Only 500 Yen!

世界中から最新の話題作・注目作を一挙上映! あなたの観たい映画はココにある。 The latest and most talked-about films from around the world! All the films you want to see are right here! 前売券は10月8日(土)より チケットぴあ・ローソンチケットにて発売! 学生の方は当日券が500円でご購入いただけます。 Advance tickets go on sale from Saturday October 8 via Ticket PIA and Lawson Ticket! Same day tickets available to students for only 500 yen! Believe! The power of films. How to purchase tickets 信じよう。映画の力。 チケット購入方法 今年、第24回を迎える東京国際映画祭は、引き続き「エコロジー」をテーマとした取り組みを展開します。今回の震災によって、日 本は課題先進国として世界中から大きな関心を集めています。そして、この課題に立ち向かう姿は、世界中から注目を集めています。 地球のために何ができるかをテーマとする東京国際映画祭は、「映画祭だからできる」「映画を通じてできる」ことを真摯に考え、日 本の未来に対して、夢や希望を持てる機会を提供することが役割だと思っています。 This year marks the 24th edition of Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF). After the March 11th earthquake and tsunami, the whole world is watching Japan to see how we will remain strong and overcome the challenges we face. As a festival that asks how people and nature can co-exist, TIFF must consider its role in this time of crisis チラシや公式サイト( )などで、観たい作品と日時が決まったら、チケットを買おう! and use the power of lms to encourage and support the people and reassure them of Japan's future. www.tiff-jp.net 公式オープニング OFFICIAL OPENING 3D上映 3D screening 当日券にはオトクな学生料金(500円) 前売券完売の上映も当日券を 三銃士/王妃の首飾りとダ・ヴィンチの飛行船 (ドイツ=フランス=イギリス) もあります(。劇場窓口で学生証要提示) 若干枚数販売いたします。 THE THREE MUSKETEERS (Germany=France=UK) ■監督:ポール・W・S・アンダーソン [2011/111min./English] 10/8(土)から一般販売 (土)ー (日) ■出演:ローガン・ラーマン、ミラ・ジョヴォヴィッチ、 当日券を買う 10/22 10/30 オーランド・ブルーム、クリストフ・ヴァルツ 10.22 Sat 16:30 at Roppongi 2 ※公式&特別オープニング・公式クロージング作品の当日学生料金はございません。 ■Director:Paul W.S. Anderson 10.22 Sat 20:30 at Roppongi 2 ※詳細はP19をご参照ください。 ■ : Cast Logan Lerman, Milla Jovovich, 10.22 Sat 20:40 at Roppongi 5 Orlando Bloom, Christoph Waltz ●ゲスト:ポール・W・S・アンダーソン、ローガン・ラーマ © 2011 Constantin Film Produktion GmbH, NEF ン、ミラ・ジョヴォヴィッチ、ガブリエラ・ワイルド Productions, S.A.S. -

Ninagawa Company Kafka on the Shore Based on the Book by Haruki Murakami Adapted for the Stage by Frank Galati

Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 23 –26 David H. Koch Theater Ninagawa Company Kafka on the Shore Based on the book by Haruki Murakami Adapted for the stage by Frank Galati Directed by Yukio Ninagawa Translated by Shunsuke Hiratsuka Set Designer Tsukasa Nakagoshi Costume Designer Ayako Maeda Lighting Designer Motoi Hattori Sound Designer Katsuji Takahashi Hair and Make-up Designers Yoko Kawamura , Yuko Chiba Original Music Umitaro Abe Chief Assistant Director Sonsho Inoue Assistant Director Naoko Okouchi Stage Manager Shinichi Akashi Technical Manager Kiyotaka Kobayashi Production Manager Yuichiro Kanai Approximate performance time: 3 hours, including one intermission Major support for Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is made possible in part with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. The Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of Kafka on the Shore is made possible in part by generous support from the LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust. Additional support provided by Mitsui & Co. (U.S.A.), Inc., Marubeni America Corporation, Mitsubishi Corporation (Americas), Sumitomo Corporation of Americas, ITOCHU International Inc., Mitsubishi Heavy Industries America, Inc., and Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal U.S.A., Inc. Co-produced by Saitama Arts Foundation, Tokyo Broadcasting System Television, Inc., and HoriPro, Inc. LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2015 KAFKA ON THE SHORE Greeting from HoriPro Inc. HoriPro Inc., along with our partners Saitama Arts Foundation and Tokyo Broadcasting System Television Inc., is delighted that we have once again been invited to the Lincoln Center Festival , this time to celebrate the 80th birthday of director, Yukio Ninagawa, who we consider to be one of the most prolific directors in Japanese theater history. -

Filmography of Case Study Films (In Chronological Order of Release)

FILMOGRAPHY OF CASE STUDY FILMS (IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER OF RELEASE) Kairo / Pulse 118 mins, col. Released: 2001 (Japan) Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa Screenplay: Kiyoshi Kurosawa Cinematography: Junichiro Hayashi Editing: Junichi Kikuchi Sound: Makio Ika Original Music: Takefumi Haketa Producers: Ken Inoue, Seiji Okuda, Shun Shimizu, Atsuyuki Shimoda, Yasuyoshi Tokuma, and Hiroshi Yamamoto Main Cast: Haruhiko Kato, Kumiko Aso, Koyuki, Kurume Arisaka, Kenji Mizuhashi, and Masatoshi Matsuyo Production Companies: Daiei Eiga, Hakuhodo, Imagica, and Nippon Television Network Corporation (NTV) Doruzu / Dolls 114 mins, col. Released: 2002 (Japan) Director: Takeshi Kitano Screenplay: Takeshi Kitano Cinematography: Katsumi Yanagijima © The Author(s) 2016 217 A. Dorman, Paradoxical Japaneseness, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-55160-3 218 FILMOGRAPHY OF CASE STUDY FILMS… Editing: Takeshi Kitano Sound: Senji Horiuchi Original Music: Joe Hisaishi Producers: Masayuki Mori and Takio Yoshida Main Cast: Hidetoshi Nishijima, Miho Kanno, Tatsuya Mihashi, Chieko Matsubara, Tsutomu Takeshige, and Kyoko Fukuda Production Companies: Bandai Visual Company, Offi ce Kitano, Tokyo FM Broadcasting Company, and TV Tokyo Sukiyaki uesutan jango / Sukiyaki Western Django 121 mins, col. Released: 2007 (Japan) Director: Takashi Miike Screenplay: Takashi Miike and Masa Nakamura Cinematography: Toyomichi Kurita Editing: Yasushi Shimamura Sound: Jun Nakamura Original Music: Koji Endo Producers: Nobuyuki Tohya, Masao Owaki, and Toshiaki Nakazawa Main Cast: Hideaki Ito, Yusuke Iseya, Koichi Sato, Kaori Momoi, Teruyuki Kagawa, Yoshino Kimura, Masanobu Ando, Shun Oguri, and Quentin Tarantino Production Companies: A-Team, Dentsu, Geneon Entertainment, Nagoya Broadcasting Network (NBN), Sedic International, Shogakukan, Sony Pictures Entertainment (Japan), Sukiyaki Western Django Film Partners, Toei Company, Tokyu Recreation, and TV Asahi Okuribito / Departures 130 mins, col. -

P38-39 Layout 1

lifestyle THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2013 MUSIC & MOVIES True Blood to end its run next year Photo shows Japanese actor Ken Watanabe gestures during an interview in Tokyo. — AP race yourselves, “True Blood” fans; dents of Bon Temps, but I look forward to the end is near. HBO Programming what promises to be a fantastic final Watanabe stars in Bpresident Michael Lombardo said chapter of this incredible show.” on Tuesday that the vampire drama will Brian Buckner, who took the reins for end its run next year following its sev- the show’s sixth season, said that he was enth season, which will launch next sum- “enormously proud” to be part of the Eastwood’s ‘Unforgiven’ remake mer. In a statement, Lombardo called series.”I feel enormously proud to have “True Blood” - which saw the departure been a part of the ‘True Blood’ family he Japanese remake of Clint Eastwood’s really good versus evil, according to self. And they were asking me: Who are of showrunner Alan Ball prior to its sixth since the very beginning,” says Brian ‘Unforgiven’ isn’t a mere cross-cultural Watanabe.The remake examines those issues you?”Watanabe stressed he was proud of the season - “nothing short of a defining Buckner. “I guarantee that there’s not a Tadaptation but more a tribute to the uni- further, reflecting psychological complexities legacy of Japanese films, a legacy he has helped show for HBO.”‘True Blood’ has been more talented or harder-working cast versal spirit of great filmmaking for its star Ken and introducing social issues not in the original, create in a career spanning more than three nothing short of a defining show for and crew out there, and I’d like to extend Watanabe.”I was convinced from the start that such as racial discrimination.”It reflects the decades, following legends like Toshiro Mifune HBO,” Lombardo said. -

Third Year Major Special Subject RECEPTIONS of GREEK TRAGEDY Dr Pantelis Michelakis and Dr Vanda Zajko Teaching Block 2: 2008-9 Unit Code CLAS32347: 40 Credits

Third Year Major Special Subject RECEPTIONS OF GREEK TRAGEDY Dr Pantelis Michelakis and Dr Vanda Zajko Teaching Block 2: 2008-9 Unit Code CLAS32347: 40 Credits This unit will take as its focus six of the most influential ancient Greek plays and moments in their reception history in the 20th Century. It will explore the broad question of how the modern world has appropriated Greek drama to make sense of and interrogate its own identities. We will study a selection of theoretical, theatrical and cinematic texts which raise important issues about the possibility of cultural translation and the politicisation of the classical past. We will consider a number of the following questions: What is tragedy? To what extent is it a theoretical concept or a set of formal generic conventions? What is reception? How do reworkings of Greek tragedy in a variety of media contribute to ongoing debates about the changing images of what constitutes the classical? Does the study of texts in performance pose particular problems for reception history? The themes addressed will include the role of genre, Marxism, colonisation, the nature of modernity, psychoanalysis, feminism, memory and history, elitist and popular cultures. On successful completion of this unit students should: • be familiar with the differing ways in which tragedy has been configured in the texts studied, and the uses to which these have been put • have developed their skills in reading and interpreting different kinds of texts in relation to issues of reception and translation • be able to -

Shakespeare and East Asia Alexa Alice Joubin

New From Oxford Shakespeare and East Asia Alexa Alice Joubin 30% OFF ow did Kurosawa influence George Lucas and Star Wars? Why do critics repeatedly use the adjective “Shakespearean” to Hdescribe Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019)? What are the connections between cinematic portrayals of transgender figures and disability? Shakespeare and East Asia analyzes Japanese innovations in sound and spectacle; Sinophone uses of Shakespeare for social reparation; conflicting reception of South Korean films and touring productions to London and Edinburgh; and multilingualism in cinema and diasporic theatre in Singapore and the UK. Features • The first monograph on Shakespeare on stage and on screen in East Asia in comparative contexts • Presents knowledge of hitherto unknown films and stage adaptations • Studies works from Japan, China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, and the UK • The glossary and chronology provide orientation regarding specialized vocabulary and timeline January 2021 (UK) | March 2021 (US) Oxford Shakespeare Topics Paperback | 9780198703570 | 272 pages £16.99 £11.89 | $20.00 $14.00 Hardback | 9780198703563 | 272 pages £50.00 £35.00 | $65.00 $45.50 Alexa Alice Joubin is Professor of English, Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies, Theatre, East Asian Languages and Literatures, and International Affairs at George Washington University where she serves as founding Co-director of the Digital Humanities Institute. Order online at www.oup.com/academic with promo code AAFLYG6 to save 30% OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 8/12/2020, SPi Contents List of Illustrations xi A Note on the Text xiii Prologue: The Cultural Meanings of Shakespeare and Asia Today 1 1. “To unpath’d waters, undream’d shores”: Sound and Spectacle 22 2. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

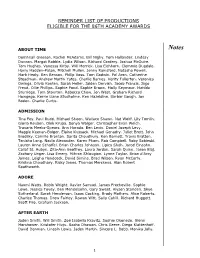

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

Festival/Tokyo Press Release

Festival Outline Name Festival/Tokyo 09 spring Time・Venues Feb 26 (Thu) – Mar 29 (Sun), 2009 Tokyo Metropolitan Art Space Medium Hall, Small Hall 1&2 Owlspot Theater (Toshima Performing Arts Center) Nishi-Sugamo Arts Factory, and others Program 14 performances presented by Festival/Tokyo 5 performances co-presented by Festival/Tokyo Festival/Tokyo Projects (Symposium/Station/Crew) Organized by Tokyo Metropolitan Government Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture Festival/Tokyo Executive Committee Toshima City, Toshima Future Culture Foundation, Arts Network Japan (NPO-ANJ) Co-organized by Japanese Centre of International Theatre Institute (ITI/UNESCO) Co-produced by The Japan Foundation Sponsored by Asahi Breweries, Ltd., Shiseido Co., Ltd. Supported by Asahi Beer Arts Foundation Endorsed by Ministry of Foreign Affairs, GEIDANKYO, Association of Japanese Theatre Companies Co-operated by The Tokyo Chamber of Commerce and Industry Toshima, Toshima City Shopping Street Federation, Toshima City Federation, Toshima City Tourism Association, Toshima Industry Association, Toshima Corporation Association Co-operated by Poster Hari’s Company Supported by the Agency for Cultural Affairs Government of Japan Related projects Tokyo Performing Arts Market 2009 2 Introduction Stimulated by the distinctive power of the performing arts and the abundant imagination of the artists, Tokyo Metropolitan Government and the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture launches a new performing arts festival, the Festival/Tokyo, together with the Festival/Tokyo Executive Committee (Toshima City, Toshima Future Cultural Foundation and NPO Arts Network Japan), as part of the Tokyo Culture Creation Project, a platform for strong communication and “real” experiences. The first Festival/Tokyo will be held from February 26 to March 29 in three main venues in the Ikebukuro and Toshima area, namely the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Space, Owlspot Theater and the Nishi-Sugamo Art Factory.