Obsah / Contents Dejiny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften Des Historischen Kollegs

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften des Historischen Kollegs Herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching Kolloquien 91 The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Herausgegeben von Holger Afflerbach An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Schriften des Historischen Kollegs herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching in Verbindung mit Georg Brun, Peter Funke, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, Martin Jehne, Susanne Lepsius, Helmut Neuhaus, Frank Rexroth, Martin Schulze Wessel, Willibald Steinmetz und Gerrit Walther Das Historische Kolleg fördert im Bereich der historisch orientierten Wissenschaften Gelehrte, die sich durch herausragende Leistungen in Forschung und Lehre ausgewiesen haben. Es vergibt zu diesem Zweck jährlich bis zu drei Forschungsstipendien und zwei Förderstipendien sowie alle drei Jahre den „Preis des Historischen Kollegs“. Die Forschungsstipendien, deren Verleihung zugleich eine Auszeichnung für die bisherigen Leis- tungen darstellt, sollen den berufenen Wissenschaftlern während eines Kollegjahres die Möglich- keit bieten, frei von anderen Verpflichtungen eine größere Arbeit abzuschließen. Professor Dr. Hol- ger Afflerbach (Leeds/UK) war – zusammen mit Professor Dr. Paul Nolte (Berlin), Dr. Martina Steber (London/UK) und Juniorprofessor Simon Wendt (Frankfurt am Main) – Stipendiat des Historischen Kollegs im Kollegjahr 2012/2013. Den Obliegenheiten der Stipendiaten gemäß hat Holger Afflerbach aus seinem Arbeitsbereich ein Kolloquium zum Thema „Der Sinn des Krieges. Politische Ziele und militärische Instrumente der kriegführenden Parteien von 1914–1918“ vom 21. -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

CDSG Special Tour to Sweden's Defenses

CDSG Special Tour to Sweden’s Defenses August 25th to September 3rd, 2021 – Four Months Out One of Three Adjoining Tours Terry McGovern The CDSG and FSG have organized special overlapping tours to Sweden’s defenses in 2021 (subject to developments with the COVID-19 pandemic). This is due to each group’s different focus, mode of transport/lodging, and duration of tour. By providing these tour options, we hope to better serve each of our member’s needs. These tours are being organized by Sweden’s leading fortification tour expert, Lars Hasson, and his tour company, Bunker Tours. He has designed a 9-day tour to the “best” of Sweden’s modern defenses for the CDSG which would take us across the breath of Sweden. He is also organized an 8-day tour for the FSG that would overlap with the CDSG tour so our two groups would travel together for 4 days. You could attend just the FSG tour or just the CDSG tour or both tours for a total of 13 days. Lars has also organized a 2-day “pre-tour” for those who want to see the Cold War defenses around Copenhagen. If you joined all three tours you would have 15 days of both Swedish and Danish fortifications and artillery. The CDSG’s 9-day tour is planned to start and end at Stockholm’s International Airport. You would need to book and pay for your own flights. The round-trip fare from Washington, DC, recently was $1,033 via Iceland. We would use shared rental cars as the size of the tour group would be limited to around 20 members. -

Thesis.Pdf (7.518Mb)

“Let’s Go Back to Go Forward” History and Practice of Schooling in the Indigenous Communities in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh Mohammed Mahbubul Kabir June 2009 Master Thesis Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Tromsø, Norway ‘‘Let’s Go Back to Go Forward’’ History and Practice of Schooling in the Indigenous Communities in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh Thesis submitted by: Mohammed Mahbubul Kabir For the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Tromsø, Norway June 2009 Supervised by: Prof. Bjørg Evjen, PhD. 1 Abstract This research deals with the history of education for the indigenous peoples in Chittagong Hills Tracts (CHT) Bangladesh who, like many places under postcolonial nation states, have no constitutional recognition, nor do their languages have a place in the state education system. Comprising data from literature and empirical study in CHT and underpinned on a conceptual framework on indigenous peoples’ education stages within state system in the global perspective, it analyzes in-depth on how the formal education for the indigenous peoples in CHT was introduced, evolved and came up to the current practices. From a wider angle, it focuses on how education originally intended to ‘civilize’ indigenous peoples subsequently, in post colonial era, with some change, still bears that colonial legacy which is heavily influenced by hegemony of ‘progress’ and ‘modernism’ (anti-traditionalism) and serves to the non-indigenous dominant group interests. Thus the government suggested Bengali-based monolingual education practice which has been ongoing since the beginning of the nation-state for citizens irrespective of ethnic and lingual background, as this research argued, is a silent policy of assimilation for the indigenous peoples. -

MUSLIM LEADERSHIP in U. P. 1906-1937 ©Ottor of ^Liilogoplip

MUSLIM LEADERSHIP IN U. P. 1906-1937 OAMAV''^ ***' THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF ©ottor of ^liilogoplip IN Jlis^torp Supervisor Research scholar umar cKai Head Department of History Banaras Hindu University VaranaSi-221005 FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY VARANASI-221005 Enrolment No.-l 73954 Year 1994 D©NATED BY PROF Z. U. SIDDIQUI DEPT. OF HISTORY. A.M.U. T5235 Poll * TtU. OJfiet : BADUM Hindu Univenity Q»3H TeUphone : 310291—99 (PABX) Sailwaj/Station Vkranui Cantt. SS^^/ Telex ;645 304 BHU IN Banaras Hindu University VARANASI—221005 R^. No..^ _ IMPARWBif 99 HliiOllir 2)ate<i - 9lftlfltilt Bft#fi titii Stall flf Ifti ffti1?t QfilifllfttI !Uiiitii X te*M^ c«rtify tHat ttM thatit •! Sti A^«k Kunat fttl. MiltUd ^Htfllii tM&mw^tp III U.F, ElitwMfi (t9%^im)»* Htm f««i»««^ fdMlAi iHMlit mf awp«rviai«n in tti« D»p«ftMifit of Hitt^y* Facility 9i So€i«d SdL«nc«t« n&ntwmM Hindu Ufiiv«rtity« ™—- j>v ' 6 jjj^ (SUM.) K.S. SMitte 0»»««tMllt of ^tj^£a»rtmentrfHj,,0| ^ OO^OttMOt of Hittflf SaAovoo Hin^ llRiiSaSu^iifi Sec .. ^^*^21. »«»•»•• Htm At Uiivovoity >^otflR«ti • 391 005' Dep«tfY>ent of History FACULTY OF SOCIAL S' ENCES Bsnafas Hir-y Unlvacsitv CONTENTS Page No. PREFACE 1 - IV ARBRBVIATIONS V INTRODUCTION ... 1-56 CHAPTER I : BIRTH OF fvUSLiM LEAaJE AND LEADERSHIP IN U .P . UPTO 1916 ... 57-96 CHAPTER II MUSLIM LEADERSHIP IN U .P . DURING KHILAFAT AND NON CO-OPERATION MO ^fAENT ... 97-163 CHAPTER III MUSLIM POLITICS AND LEADERSHIP IN U.P, DURING Sy/AR.AJIST BRA ...164 - 227 CHAPTER IV : MUSLL\^S ATflTUDE AND LEADERSHIP IN U.P. -

University of Cincinnati

! "# $ % & % ' % !" #$ !% !' &$ &""! '() ' #$ *+ ' "# ' '% $$(' ,) * !$- .*./- 0 #!1- 2 *,*- Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2010 by Wolfgang Lueckel B.A. (equivalent) in German Literature, Universität Mainz, 2003 M.A. in German Studies, University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: Sara Friedrichsmeyer, Ph.D. Committee Members: Todd Herzog, Ph.D. (second reader) Katharina Gerstenberger, Ph.D. Richard E. Schade, Ph.D. ii Abstract In my dissertation “Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture,” I investigate the portrayal of the nuclear age and its most dreaded fantasy, the nuclear apocalypse, in German fictionalizations and cultural writings. My selection contains texts of disparate natures and provenance: about fifty plays, novels, audio plays, treatises, narratives, films from 1946 to 2009. I regard these texts as a genre of their own and attempt a description of the various elements that tie them together. The fascination with the end of the world that high and popular culture have developed after 9/11 partially originated from the tradition of nuclear fiction since 1945. The Cold War has produced strong and lasting apocalyptic images in German culture that reject the traditional biblical apocalypse and that draw up a new worldview. In particular, German nuclear fiction sees the atomic apocalypse as another step towards the technical facilitation of genocide, preceded by the Jewish Holocaust with its gas chambers and ovens. -

Adult Education and Indigenous Peoples in Norway. International Survey on Adult Education for Indigenous Peoples

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 458 367 CE 082 168 AUTHOR Lund, Svein TITLE Adult Education and Indigenous Peoples in Norway. International Survey on Adult Education for Indigenous Peoples. Country Study: Norway. INSTITUTION Nordic Sami Inst., Guovdageaidnu, Norway.; United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Hamburg (Germany). Inst. for Education. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 103p.; For other country studies, see CE 082 166-170. Research supported by the Government of Norway and DANIDA. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.unesco.org/education/uie/pdf/Norway.pdf. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Access to Education; Acculturation; *Adult Education; Adult Learning; Adult Students; Colleges; Computers; Cultural Differences; Culturally Relevant Education; Delivery Systems; Dropouts; Educational Administration; Educational Attainment; *Educational Environment; Educational History; Educational Needs; Educational Opportunities; Educational Planning; *Educational Policy; *Educational Trends; Equal Education; Foreign Countries; Government School Relationship; Inclusive Schools; *Indigenous Populations; Language Minorities; Language of Instruction; Needs Assessment; Postsecondary Education; Professional Associations; Program Administration; Public Policy; Rural Areas; Secondary Education; Self Determination; Social Integration; Social Isolation; State of the Art Reviews; Student Characteristics; Trend Analysis; Universities; Vocational Education; Womens Education IDENTIFIERS Finland; Folk -

Networks and Alliances

THE CONTEMPORARY ART DAYS SUMMIT 2018 NETWORKS AND ALLIANCES samtidskonstdagarna.se/en 14–16 November 2018 Boden/Luleå 13 November Pre-summit visit to Kiruna The Contemporary Art Days is the annual contemporary art summit that brings together art professionals from across Sweden and other countries to discuss current issues for art organisations. In 2018, for the first time, the summit is organised under the aegis of the Public Art Agency Sweden. This year’s summit will focus on building networks and alliances as strate- gies for action in contemporary art organisations today. The last few years have witnessed a large increase in organisational networks across the art field in Sweden. Whether formal or informal, on a local or national scale, with Nordic or international counterparts, alliances are formed in a variety of constellations between art institutions, self-organised initiatives and other organisations. Are these networks signs of the signature strategy of the neoliberal working world? Or are they responses of mutual support and solidarity by small and mid-size art organisations in the changing political landscape and precarious economic conditions? Or are today’s networks merely new forms of age old tools for building assemblies around mutual concerns? The Contemporary Art Days 2018 presents a diverse programme comprising guest speakers, performances, site visits and workshops that will examine a variety of ways of working with networks and building strategic alliances. The summit is held in the region of Norrbotten in the north of Sweden. A preview of the 2018 Luleå Biennial is included in the programme, as well as a pre-summit site visit to Kiruna, a mining town that is being relocated and rebuilt. -

STRATEGIC FORUM National Defense University

January 2020 STRATEGIC FORUM National Defense University About the Authors Håkon Lunde Saxi, Ph.D., is an As- Baltics Left of Bang: Nordic sociate Professor at the Norwegian Defence University College. Bengt Total Defense and Implications Sundelius is a Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the Swedish Defense University. Brett Swaney is an for the Baltic Sea Region Assistant Research Fellow in the Center for Strategic Research, Institute for Na- tional Strategic Studies, at the National by Håkon Lunde Saxi, Bengt Sundelius, and Brett Defense University. Swaney Key Points ponsored by the U.S. National Defense University (NDU) and the Swed- ish National Defense University, this paper is the second in a series of ◆◆ Nordic states (Norway, Sweden, and Finland) efforts to enhance Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Forums dedicated to societal resilience through unique the multinational exploration of the strategic and defense challenges faced by “total defense” and “comprehen- S sive security” initiatives are unlikely the Baltic states. The December 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy described to change the near-term strategic Russia as “using subversive measures to weaken the credibility of America’s com- calculus of Russia. Over time, how- ever, a concerted application of to- mitment to Europe, undermine transatlantic unity, and weaken European insti- tal defense in harmony with Article tutions and governments.”1 The U.S. and European authors of this paper, along 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty will with many others, came together in late 2017 to explore possible responses to aid in the resilience to, and deter- rence of, Russian hostile measures the security challenges facing the Baltic Sea Region (BSR). -

Social Policies and Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan

Faculty of Social Sciences University of Helsinki Finland SOCIAL POLICIES AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN TAIWAN ELDERLY CARE AMONG THE TAYAL I-An Gao (Wasiq Silan) DOCTORAL THESIS To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in lecture room 302, Athena, on 18 May 2021, at 8 R¶FORFN. Helsinki 2021 Publications of the Faculty of Social Sciences 186 (2021) ISSN 2343-273X (print) ISSN 2343-2748 (online) © I-An Gao (Wasiq Silan) Cover design and visualization: Pei-Yu Lin Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] ISBN 978-951-51-7005-7 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-7006-4 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2021 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores how Taiwanese social policy deals with Indigenous peoples in caring for Tayal elderly. By delineating care for the elderly both in policy and practice, the study examines how relationships between indigeneity and coloniality are realized in today’s multicultural Taiwan. Decolonial scholars have argued that greater recognition of Indigenous rights is not the end of Indigenous peoples’ struggles. Social policy has much to learn from encountering its colonial past, in particular its links to colonization and assimilation. Meanwhile, coloniality continues to make the Indigenous perspective invisible, and imperialism continues to frame Indigenous peoples’ contemporary experience in how policies are constructed. This research focuses on tensions between state recognition and Indigenous peoples’ -

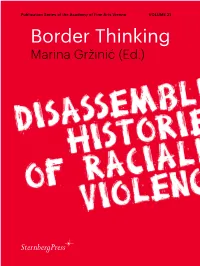

Border Thinking

Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna VOLUME 21 Border Thinking Marina Gržinić (Ed.) Border Thinking Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence Border Thinking Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence Marina Gržinić (Ed.) Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Eva Blimlinger, Andrea B. Braidt, Karin Riegler (Series Eds.) VOLUME 21 On the Publication Series We are pleased to present the latest volume in the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna’s publication series. The series, published in cooperation with our highly com- mitted partner Sternberg Press, is devoted to central themes of contemporary thought about art practices and theories. The volumes comprise contribu- tions on subjects that form the focus of discourse in art theory, cultural studies, art history, and research at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and represent the quintessence of international study and discussion taking place in the respective fields. Each volume is published in the form of an anthology, edited by staff members of the academy. Authors of high international repute are invited to make contributions that deal with the respective areas of emphasis. Research activities such as international conferences, lecture series, institute- specific research focuses, or research projects serve as points of departure for the individual volumes. All books in the series undergo a single blind peer review. International re- viewers, whose identities are not disclosed to the editors of the volumes, give an in-depth analysis and evaluation for each essay. The editors then rework the texts, taking into consideration the suggestions and feedback of the reviewers who, in a second step, make further comments on the revised essays. -

European Charter for Regional Or Minority Language

Your ref. Our ref. Date 2006/2972 KU/KU2 ckn 18 June 2008 European Charter for Regional or Minority Language Fourth periodical report Norway June 2008 Contents Preliminary section 1. Introductory remarks 2. Constitutional and administrative structure 3. Economy 4. Demography 5. The Sámi language 6. The Kven language 7. Romanes 8. Romany 1 Part I 1. Implementation provisions 2. Bodies or organisations working for the protection and development of regional or minority language 3. Preparation of the fourth report 4. Measures to disseminate information about the rights and duties deriving from the implementation of the Charter in Norwegian legislation 5. Measures to implement the recommendations of the Committee of Ministers Part II 1. Article 7 Objects and principles 2. Article 7 paragraph 1 sub-paragraphs f, g, h 3. Article 7 paragraph 3 4. Article 7 paragraph 4 Part III 1. Article 8 Educations 2. Article 9 Judicial authorities 3. Article 9 paragraph 3 Translation 4. Article 10 Administrative authorities and public service 5. Article 10 paragraph 5 6. Article 11 Media o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph a o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph b o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph c o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph e o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph f o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph g o Article 11 paragraph 2 7. Article 12 Cultural activities and facilities 8. Article 13 Economic and social life Preliminary section 1. Introductory remarks This fourth periodical report describes the implementation of the provisions of the European Charter for regional or minority languages in Norway.