Social Policies and Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

Villains of Formosan Aboriginal Mythology ABSTRACT

Villains of Formosan Aboriginal Mythology Aaron Valdis Gauss 高加州 Intergrams 20.1 (2020): http://benz.nchu.edu.tw/~intergrams/intergrams/201/201-gauss.pdf ISSN: 1683-4186 ABSTRACT In Western fairy tales, the role of the villain is often reserved for the elderly woman. The villains of Snow White, The Little Mermaid, Rapunzel, Hansel and Gretel, Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty are all witches; women who wield dark magic to maledict the innocent. In stark contrast, Formosan aboriginal mythology villains take on decidedly dissimilar roles. In the Paiwan story of Pali, for example, Pali is a young boy who, through no fault of his own, is cursed with a pair of red eyes that instantaneously kill all living things that they see. Pali’s identity and the reasons for his evil acts are diametrically opposed to those found in “typical” Western tales. This article investigates the identities and motives of villains in Formosan aboriginal stories. Despite the unfortunate lack of related material in English, Taiwan Indigene: Meaning Through Stories (臺灣原住民的神話與傳說套書) offers a unique look into the redirection of English literature to source from a wider geographic and ethnographic perspective and serves as the primary data source for this research. Works done in this vein indicate a greater openness toward the “other” ethnic groups that remain almost completely absent from English literature. The identities of the villains and the elements motivating their nefarious deeds are investigated in detail. Can the villains of such stories be grouped broadly according to identity? If so, what aspects can be used to describe that identity? What root causes can be identified with regard to the malevolent acts that they perpetrate? The ambitions behind this study include facilitating a lifting of the veil on the mysterious cultures native to Formosa and promoting a greater understanding of, and appreciation for, the rich and complex myths of the Formosan aboriginal peoples. -

University of the Arctic: the First Year Report to the Senior Arctic Officials of the Arctic Council Oulu, Finland, May 16, 2002

UNIVERSITY OF THE ARCTIC University of the Arctic: the First Year Report to the Senior Arctic Officials of the Arctic Council Oulu, Finland, May 16, 2002 Introduction The University of the Arctic was officially launched in Rovaniemi, Finland, in conjunction with the first Senior Arctic Officials of the Arctic Council meeting under Finland’s chairmanship and the 10th anniversary of the Rovaniemi process on June 12, 2001. Over 200 people celebrated the Launch of the new University. The guest speakers included Maija Rask, Finland’s Minister of Education, who invited all the Arctic governments to work hard at finding collaborative ways to fund the University of the Arctic and its program, and Professor Asgeir Brekke from the University of Tromsø in Norway , the Chair of the Council of the University of the Arctic since the inception of the idea, who symbolically passed on the Council’s gavel to Sally Adams Webber, President of Yukon College in Canada. The Launch marked the shift from planning of governance structures and programs to the actual implementation of programs. The first year of operation for the University of the Arctic has meant real students, real programs, and a growing enthusiasm and expectation of more to come for those students. The first evaluations of the University of the Arctic’s pilot programs, are being conducted at the time of writing this report. Preliminary results from these evaluations show that, first of all, the early enthusiasts were right in saying that we do need structural solutions to address the need for truly Circumpolar education that takes the needs of the primary client group to heart. -

Thesis.Pdf (7.518Mb)

“Let’s Go Back to Go Forward” History and Practice of Schooling in the Indigenous Communities in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh Mohammed Mahbubul Kabir June 2009 Master Thesis Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Tromsø, Norway ‘‘Let’s Go Back to Go Forward’’ History and Practice of Schooling in the Indigenous Communities in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh Thesis submitted by: Mohammed Mahbubul Kabir For the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Tromsø, Norway June 2009 Supervised by: Prof. Bjørg Evjen, PhD. 1 Abstract This research deals with the history of education for the indigenous peoples in Chittagong Hills Tracts (CHT) Bangladesh who, like many places under postcolonial nation states, have no constitutional recognition, nor do their languages have a place in the state education system. Comprising data from literature and empirical study in CHT and underpinned on a conceptual framework on indigenous peoples’ education stages within state system in the global perspective, it analyzes in-depth on how the formal education for the indigenous peoples in CHT was introduced, evolved and came up to the current practices. From a wider angle, it focuses on how education originally intended to ‘civilize’ indigenous peoples subsequently, in post colonial era, with some change, still bears that colonial legacy which is heavily influenced by hegemony of ‘progress’ and ‘modernism’ (anti-traditionalism) and serves to the non-indigenous dominant group interests. Thus the government suggested Bengali-based monolingual education practice which has been ongoing since the beginning of the nation-state for citizens irrespective of ethnic and lingual background, as this research argued, is a silent policy of assimilation for the indigenous peoples. -

Adult Education and Indigenous Peoples in Norway. International Survey on Adult Education for Indigenous Peoples

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 458 367 CE 082 168 AUTHOR Lund, Svein TITLE Adult Education and Indigenous Peoples in Norway. International Survey on Adult Education for Indigenous Peoples. Country Study: Norway. INSTITUTION Nordic Sami Inst., Guovdageaidnu, Norway.; United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Hamburg (Germany). Inst. for Education. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 103p.; For other country studies, see CE 082 166-170. Research supported by the Government of Norway and DANIDA. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.unesco.org/education/uie/pdf/Norway.pdf. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Access to Education; Acculturation; *Adult Education; Adult Learning; Adult Students; Colleges; Computers; Cultural Differences; Culturally Relevant Education; Delivery Systems; Dropouts; Educational Administration; Educational Attainment; *Educational Environment; Educational History; Educational Needs; Educational Opportunities; Educational Planning; *Educational Policy; *Educational Trends; Equal Education; Foreign Countries; Government School Relationship; Inclusive Schools; *Indigenous Populations; Language Minorities; Language of Instruction; Needs Assessment; Postsecondary Education; Professional Associations; Program Administration; Public Policy; Rural Areas; Secondary Education; Self Determination; Social Integration; Social Isolation; State of the Art Reviews; Student Characteristics; Trend Analysis; Universities; Vocational Education; Womens Education IDENTIFIERS Finland; Folk -

Open Dissertation Draft Revised Final.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School ICT AND STEM EDUCATION AT THE COLONIAL BORDER: A POSTCOLONIAL COMPUTING PERSPECTIVE OF INDIGENOUS CULTURAL INTEGRATION INTO ICT AND STEM OUTREACH IN BRITISH COLUMBIA A Dissertation in Information Sciences and Technology by Richard Canevez © 2020 Richard Canevez Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2020 ii The dissertation of Richard Canevez was reviewed and approved by the following: Carleen Maitland Associate Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Daniel Susser Assistant Professor of Information Sciences and Technology and Philosophy Lynette (Kvasny) Yarger Associate Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Craig Campbell Assistant Teaching Professor of Education (Lifelong Learning and Adult Education) Mary Beth Rosson Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Director of Graduate Programs iii ABSTRACT Information and communication technologies (ICTs) have achieved a global reach, particularly in social groups within the ‘Global North,’ such as those within the province of British Columbia (BC), Canada. It has produced the need for a computing workforce, and increasingly, diversity is becoming an integral aspect of that workforce. Today, educational outreach programs with ICT components that are extending education to Indigenous communities in BC are charting a new direction in crossing the cultural barrier in education by tailoring their curricula to distinct Indigenous cultures, commonly within broader science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) initiatives. These efforts require examination, as they integrate Indigenous cultural material and guidance into what has been a largely Euro-Western-centric domain of education. Postcolonial computing theory provides a lens through which this integration can be investigated, connecting technological development and education disciplines within the parallel goals of cross-cultural, cross-colonial humanitarian development. -

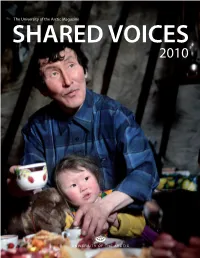

Shared Voices Magazine 2010

The University of the Arctic Magazine SHARED VOICES 2010 UArctic VP Indigenous Building on Classroom Connections: UArctic's Vice-President The Development of 06 Indigenous position is the latest initiative towards building a UArctic Student Association indigenous leadership in UArctic Two former students of governance and program activities. 32 the UArctic write about the Newly appointed VP Indigenous need to create a student association and long-time UArctic supporter, and the advantages that such a Jan Henry Keskitalo, explains the group could provide for the future opportunities on the horizon. development of the organisation. Can Good Governance Save the Arctic? The Arctic is experiencing a profound 14 transformation driven by the interacting forces of climate change and globalization. The Arctic Governance Project is one group examining the role of governance in these transformations and exploring different ways that the Arctic's existing governance systems can maximize a cooperative future. Student Profile: Siberian Food – a Raw Deal Chen Yichao Not for the Fainthearted Doing something new is Professional chef, columnist 21 nothing new for Chinese 16 and TV icon Andreas Viestad Polar Law Student Chen Yichao. shares his experiences with local See how this student of human cuisine during his travels in Western rights lived and learned in the Siberia, and offers a recipe for the Arctic, finding ways of applying region's famous Stroganina dish. his studies to Arctic indigenous peoples. The University of the Arctic Shared Voices Magazine 2010 Editorial Team / Outi Snellman, Lars Kullerud, Scott Forrest, Harry Borlase UArctic International Secretariat Editor in Chief / Outi Snellman University of Lapland Managing Editor / Scott Forrest Box 122 96101 Rovaniemi Finland Editorial Assistant / Harry Borlase [email protected] Graphic Design & Layout / Puisto Design & Advertising / www.puistonpenkki.fi Tel. -

Kizh Not Tongva, E. Gary Stickel, Ph.D (UCLA)

WHY THE ORIGINAL INDIAN TRIBE OF THE GREATER LOS ANGELES AREA IS CALLED KIZH NOT TONGVA by E. Gary Stickel, Ph.D (UCLA) Tribal Archaeologist Gabrieleno Band of Mission Indians/ Kizh Nation 2016 1 WHY THE ORIGINAL INDIAN TRIBE OF THE GREATER LOS ANGELES AREA IS CALLED KIZH NOT TONGVA by E. Gary Stickel, Ph.D (UCLA) Tribal Archaeologist Gabrieleno Band of Mission Indians/ Kizh Nation The original Indian Tribe of the greater Los Angeles and Orange County areas, has been referred to variously which has lead to much confusion. This article is intended to clarify what they were called, what they want to be called today (Kizh), and what they do not want to be called (i.e. “tongva”). Prior to the invasion of foreign nations into California (the Spanish Empire and the Russian Empire) in the 1700s, California Indian Tribes did not have pan-tribal names for themselves such as Americans are used to (for example, the “Cherokee” or “Navajo” [Dine]). The local Kizh Indian People identified themselves with their associated resident village (such as Topanga, Cahuenga, Tujunga, Cucamonga, etc.). This concept can be understood if one considers ancient Greece where, before the time of Alexander the Great, the people there did not consider themselves “Greeks” but identified with their city states. So one was an Athenian from Athens or a Spartan from Sparta. Similarly the Kizh identified with their associated villages. Anthropologists, such as renowned A.L. Kroeber, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, who wrote the first “bible” of California Indians (1925), inappropriately referred to the subject tribe as the “Gabrielinos” (Kroeber 1925). -

A Circumpolar Reappraisal: the Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979)

A Circumpolar Reappraisal: The Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979) Proceedings of an International Conference held in Trondheim, Norway, 10th-12th October 2008, arranged by the Institute of Archaeology and Religious Studies, and the SAK department of the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Edited by Christer Westerdahl BAR International Series 2154 2010 Published by Archaeopress Publishers of British Archaeological Reports Gordon House 276 Ban bury Road Oxford 0X2 7ED England [email protected] www.archaeopress.com BAR S2154 A Circumpolar Reappraisal: The Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979). Proceedings of an International Conference held in Trondheim, Norway, 10th-12th October 2008, arranged by the Institute of Archaeology and Religious Studies, and the SAK department of the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2010 ISBN 978 1 4073 0696 4 Front and back photos show motifs from Greenland and Spitsbergen. © C Westerdahl 1974, 1977 Printed in England by 4edge Ltd, Hockley All BAR titles are available from: Hadrian Books Ltd 122 Banbury Road Oxford 0X2 7BP England [email protected] www.hadrianbooks.co.uk The current BAR catalogue with details of all titles in print, prices and means of payment is available free from Hadrian Books or may be downloaded from www.archaeopress.com CHAPTER 7 ARCTIC CULTURES AND GLOBAL THEORY: HISTORICAL TRACKS ALONG THE CIRCUMPOLAR ROAD William W. Fitzhugh Arctic Studies Center, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 2007J-J7072 fe// 202-(W-7&?7;./ai202-JJ7-2&&f; e-mail: fitzhugh@si. -

European Charter for Regional Or Minority Language

Your ref. Our ref. Date 2006/2972 KU/KU2 ckn 18 June 2008 European Charter for Regional or Minority Language Fourth periodical report Norway June 2008 Contents Preliminary section 1. Introductory remarks 2. Constitutional and administrative structure 3. Economy 4. Demography 5. The Sámi language 6. The Kven language 7. Romanes 8. Romany 1 Part I 1. Implementation provisions 2. Bodies or organisations working for the protection and development of regional or minority language 3. Preparation of the fourth report 4. Measures to disseminate information about the rights and duties deriving from the implementation of the Charter in Norwegian legislation 5. Measures to implement the recommendations of the Committee of Ministers Part II 1. Article 7 Objects and principles 2. Article 7 paragraph 1 sub-paragraphs f, g, h 3. Article 7 paragraph 3 4. Article 7 paragraph 4 Part III 1. Article 8 Educations 2. Article 9 Judicial authorities 3. Article 9 paragraph 3 Translation 4. Article 10 Administrative authorities and public service 5. Article 10 paragraph 5 6. Article 11 Media o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph a o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph b o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph c o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph e o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph f o Article 11 paragraph 1 sub-paragraph g o Article 11 paragraph 2 7. Article 12 Cultural activities and facilities 8. Article 13 Economic and social life Preliminary section 1. Introductory remarks This fourth periodical report describes the implementation of the provisions of the European Charter for regional or minority languages in Norway. -

Sounding Paiwan: Institutionalization and Heritage-Making of Paiwan Lalingedan and Pakulalu Flutes in Contemporary Taiwan

Ethnomusicology Review 22(2) Sounding Paiwan: Institutionalization and Heritage-Making of Paiwan Lalingedan and Pakulalu Flutes in Contemporary Taiwan Chia-Hao Hsu Lalingedan ni vuvu namaya tua qaun Lalingedan ni vuvu namaya tua luseq…… Lalingedan sini pu’eljan nu talimuzav a’uvarun Lalingedan nulemangeda’en mapaqenetje tua saluveljengen The ancestor’s nose flute is like weeping. The ancestor’s nose flute is like tears... When I am depressed, the sound of the nose flute becomes a sign of sorrow. When I hear the sound of the nose flute, I always have my lover in mind. —Sauniaw Tjuveljevelj, from the song “Lalingedan ni vuvu,” in the album Nasi1 In 2011, the Taiwanese government’s Council for Cultural Affairs declared Indigenous Paiwan lalingedan (nose flutes) and pakulalu (mouth flutes) to be National Important Traditional Arts. 2 Sauniaw Tjuveljevelj, a designated preserver of Paiwan nose and mouth flutes at the county level, released her first album Nasi in 2007, which included one of her Paiwan songs “Lalingedan ni vuvu” [“The Ancestor’s Nose Flute”]. Using both nose flute playing and singing in Paiwan language, the song shows her effort to accentuate her Paiwan roots by connecting with her ancestors via the nose flute. The lines of the song mentioned above reflect how prominent cultural discourses in Taiwan depict the instruments today; the sound of Paiwan flutes (hereafter referred to collectively as Paiwan flutes) resembles the sound of weeping, which is a voice that evokes a sense of ancestral past and “thoughtful sorrow.” However, the music of Paiwan flutes was rarely labeled as sorrowful in literature before the mid-1990s. -

Indigenous Rights and Wildlife Conservation: the Vernacularization of International Law on Taiwan

Indigenous Rights and Wildlife Conservation: The Vernacularization of International Law on Taiwan Scott Simon Professeur École d’études sociologiques et anthropologiques Université d'Ottawa Awi Mona, Chih-Wei Tsai Associate Professor Department of Educational Management National Taipei University of Education Abstract Indigenous rights and wildlife conservation laws have become two important arenas for legal pluralism in Taiwan. In a process of vernacularization, Taiwan has adopted international legal norms in indigenous rights and wildlife conservation. Local actors from legislators to conservation officers and indigenous hunters refer not only to international and state law but also to indigenous customary law and other cultural norms in their interactions. In Seediq and Truku communities, the customary law of Gaya continues to inform the ways in which local hunters and trappers manage natural resources according to their own legal norms. There are, however, different individual interpretations of Gaya, and, in the absence of adequate legal protection, many hunting activities are clandestine and difficult to regulate. Fuller political autonomy, as envisioned in both the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Taiwan’s 2005 Basic Law on Indigenous Peoples, is needed in order that indigenous peoples can construct and manage their own institutions for common resource management. This 台灣人權學刊 第三卷第一期 2015 年 6 月 頁 3~31 3 台灣人權學刊 第三卷第一期 approach bodes best for both the realization of indigenous rights and effective wildlife conservation. Keywords indigenous rights, wildlife conservation, legal pluralism, hunting, Seediq, Truku, Taiwan The Republic of China (ROC), which lost the right to represent China in the United Nations (UN) in 1971, has systematically tried to keep up with UN norms and adopt key elements of evolving international law in its sole remaining jurisdiction on Taiwan, despite the lack of enforcement mechanisms and higher transaction costs to share relevant information and best practices.