An Integrative Approach to the Hominin Record Wil Roebroeks (Ed.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grandmothers Matter

Grandmothers Matter: Some surprisingly controversial theories of human longevity Introduction Moses Carr >> Sound of rolling tongue Wanda Carey >> laughs Mariel: Welcome to Distillations, I’m Mariel Carr. Rigo: And I’m Rigo Hernandez. Mariel: And we’re your producers! We’re usually on the other side of the microphones. Rigo: But this episode got personal for us. Wanda >> Baby, baby, baby… Mariel: That’s my mother-in-law Wanda and my one-year-old son Moses. Wanda moved to Philadelphia from North Carolina for ten months this past year so she could take care of Moses while my husband and I were at work. Rigo: And my mom has been taking care of my niece and nephew in San Diego for 14 years. She lives with my sister and her kids. Mariel: We’ve heard of a lot of arrangements like the ones our families have: grandma retires and takes care of the grandkids. Rigo: And it turns out that across cultures and throughout the world scenes like these are taking place. Mariel: And it’s not a recent phenomenon either. It goes back a really long time. In fact, grandmothers might be the key to human evolution! Rigo: Meaning they’re the ones that gave us our long lifespans, and made us the unique creatures that we are. Wanda >> I’m gonna get you! That’s right! Mariel: A one-year-old human is basically helpless. We’re special like that. Moses can’t feed or dress himself and he’s only just starting to walk. Gravity has just become a thing for him. -

Growth, Learning, Play and Attachment in Neanderthal Children

This is a repository copy of The Cradle of Thought : Growth, Learning, Play and Attachment in Neanderthal children. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/83027/ Version: Submitted Version Article: Spikins, Penny orcid.org/0000-0002-9174-5168, Hitchens, Gail, Rutherford, Holly et al. (1 more author) (2014) The Cradle of Thought : Growth, Learning, Play and Attachment in Neanderthal children. Oxford Journal of Archaeology. pp. 111-134. ISSN 0262-5253 https://doi.org/10.1111/ojoa.12030 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ THE CRADLE OF THOUGHT: GROWTH, LEARNING, PLAY AND ATTACHMENT IN NEANDERTHAL CHILDREN Penny Spikins, Gail Hitchens, Andy Needham and Holly Rutherford Department of Archaeology University of York King’s Manor York YO1 7EP SUMMARY Childhood is a core stage in development, essential in the acquisition of social, practical and cultural skills. However, this area receives limited attention in archaeological debate, especially in early prehistory. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Paranthropus Boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard A

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Biological Sciences Faculty Research Biological Sciences Fall 11-28-2007 Paranthropus boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard A. Wood George Washington University Paul J. Constantino Biological Sciences, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/bio_sciences_faculty Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Wood B and Constantino P. Paranthropus boisei: Fifty years of evidence and analysis. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 50:106-132. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 50:106–132 (2007) Paranthropus boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard Wood* and Paul Constantino Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology, George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052 KEY WORDS Paranthropus; boisei; aethiopicus; human evolution; Africa ABSTRACT Paranthropus boisei is a hominin taxon ers can trace the evolution of metric and nonmetric var- with a distinctive cranial and dental morphology. Its iables across hundreds of thousands of years. This pa- hypodigm has been recovered from sites with good per is a detailed1 review of half a century’s worth of fos- stratigraphic and chronological control, and for some sil evidence and analysis of P. boi se i and traces how morphological regions, such as the mandible and the both its evolutionary history and our understanding of mandibular dentition, the samples are not only rela- its evolutionary history have evolved during the past tively well dated, but they are, by paleontological 50 years. -

Title: Drimolen Crania Indicate Contemporaneity of Australopithecus, Paranthropus and Early Homo Erectus in S

Submitted Manuscript: Confidential Title: Drimolen crania indicate contemporaneity of Australopithecus, Paranthropus and early Homo erectus in S. Africa Authors: Andy I.R. Herries1,2*†, Jesse M. Martin1†, A.B. Leece1†, Justin W. Adams3,2†, Giovanni Boschian4,2†, Renaud Joannes-Boyau5,2, Tara R. Edwards1, Tom Mallett1, Jason Massey3,6, Ashleigh Murszewski1, Simon Neuebauer7, Robyn Pickering8.9, David Strait10,2, Brian J. Armstrong2, Stephanie Baker2, Matthew V. Caruana2, Tim Denham11, John Hellstrom12, Jacopo Moggi-Cecchi13, Simon Mokobane2, Paul Penzo-Kajewski1, Douglass S. Rovinsky3, Gary T. Schwartz14, Rhiannon C. Stammers1, Coen Wilson1, Jon Woodhead12, Colin Menter13 Affiliations: 1. Palaeoscience Labs, Dept. Archaeology and History, La Trobe University, Bundoora, 3086, VIC, Australia. 2. Palaeo-Research Institute, University of Johannesburg, Gauteng Province, South Africa. 3. Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology, Biomedicine Discovery Institute, Monash University, VIC, Australia. 4. Department of Biology, University of Pisa, Italy 5. Geoarchaeology and Archaeometry Research Group (GARG), Southern Cross University, Military Rd, Lismore, 2480, NSW, Australia 6. Department of Integrative Biology and Physiology, University of Minnesota Medical School, USA 7. Department of Human Evolution, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Germany. 8. Department of Geological Sciences, University of Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa 9. Human Evolution Research Institute, University of Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa 10. Department of Anthropology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, USA 11. Geoarchaeology Research Group, School of Archaeology and Anthropology, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia 12. Earth Sciences, University of Melbourne, Australia 13. Department of Biology, University of Florence, Italy 14. Institute of Human Origins, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, U.S.A. -

O Ssakach Drapieżnych – Część 2 - Kotokształtne

PAN Muzeum Ziemi – O ssakach drapieżnych – część 2 - kotokształtne O ssakach drapieżnych - część 2 - kotokształtne W niniejszym artykule przyjrzymy się ewolucji i zróżnicowaniu zwierząt reprezentujących jedną z dwóch głównych gałęzi ewolucyjnych w obrębie drapieżnych (Carnivora). Na wczesnym etapie ewolucji, drapieżne podzieliły się (ryc. 1) na psokształtne (Caniformia) oraz kotokształtne (Feliformia). Paradoksalnie, w obydwu grupach występują (bądź występowały w przeszłości) formy, które bardziej przypominają psy, bądź bardziej przypominają koty. Ryc. 1. Uproszczone drzewo pokrewieństw ewolucyjnych współczesnych grup drapieżnych (Carnivora). Ryc. Michał Loba, na podstawie Nyakatura i Bininda-Emonds, 2012. Tym, co w rzeczywistości dzieli te dwie grupy na poziomie anatomicznym jest budowa komory ucha środkowego (bulla tympanica, łac.; ryc. 2). U drapieżnych komora ta jest budowa przede wszystkim przez dwie kości – tylną kaudalną kość entotympaniczną i kość ektotympaniczną. U kotokształtnych, w miejscu ich spotkania się ze sobą powstaje ciągła przegroda. Obydwie części komory kontaktują się ze sobą tylko za pośrednictwem małego okienka. U psokształtnych 1 PAN Muzeum Ziemi – O ssakach drapieżnych – część 2 - kotokształtne Ryc. 2. Widziane od spodu czaszki: A. baribala (Ursus americanus, Ursidae, Caniformia), B. żenety zwyczajnej (Genetta genetta, Viverridae, Feliformia). Strzałkami zaznaczono komorę ucha środkowego u niedźwiedzia i miejsce występowania przegrody w komorze żenety. Zdj. (A, B) Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (CC BY-NC-SA -

Teacher's Booklet

Ideas and Evidence at the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Teacher’s Booklet Acknowledgements Shawn Peart Secondary Consultant Annette Shelford Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Paul Dainty Great Cornard Upper School Sarah Taylor St. James Middle School David Heap Westley Middle School Thanks also to Dudley Simons for photography and processing of the images of objects and exhibits at the Sedgwick Museum, and to Adrienne Mayor for kindly allowing us to use her mammoth and monster images (see picture credits). Picture Credits Page 8 “Bag of bones” activity adapted from an old resource, source unknown. Page 8 Iguanodon images used in the interpretation of the skeleton picture resource from www.dinohunters.com Page 9 Mammoth skeleton images from ‘The First Fossil Hunters’ by Adrienne Mayor, Princeton University Press ISBN: 0-691-05863 with kind permission of the author Page 9 Both paintings of Mary Anning from the collections of the Natural History Museum © Natural History Museum, London 1 Page 12 Palaeontologists Picture from the photographic archive of the Sedgwick Museum © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 14 Images of Iguanodon from www.dinohunters.com Page 15 “Duria Antiquior - a more ancient Dorsetshire” by Henry de la Beche from the collection of the National Museums and Galleries of Wales © National Museum of Wales Page 17 Images of Deinotherium giganteum skull cast © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 19 Image of red sandstone slab © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences 2 Introduction Ideas and evidence was introduced as an aspect of school science after the review of the National Curriculum in 2000. Until the advent of the National Strategy for Science it was an area that was often not planned for explicitly. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01829-7 - Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary Ryan J. Rabett Index More information Index Abdur, 88 Arborophilia sp., 219 Abri Pataud, 76 Arctictis binturong, 218, 229, 230, 231, 263 Accipiter trivirgatus,cf.,219 Arctogalidia trivirgata, 229 Acclimatization, 2, 7, 268, 271 Arctonyx collaris, 241 Acculturation, 70, 279, 288 Arcy-sur-Cure, 75 Acheulean, 26, 27, 28, 29, 45, 47, 48, 51, 52, 58, 88 Arius sp., 219 Acheulo-Yabrudian, 48 Asian leaf turtle. See Cyclemys dentata Adaptation Asian soft-shell turtle. See Amyda cartilaginea high frequency processes, 286 Asian wild dog. See Cuon alipinus hominin adaptive trajectories, 7, 267, 268 Assamese macaque. See Macaca assamensis low frequency processes, 286–287 Athapaskan, 278 tropical foragers (Southeast Asia), 283 Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC), 23–24 Variability selection hypothesis, 285–286 Attirampakkam, 106 Additive strategies Aurignacian, 69, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 102, 103, 268, 272 economic, 274, 280. See Strategy-switching Developed-, 280 (economic) Proto-, 70, 78 technological, 165, 206, 283, 289 Australo-Melanesian population, 109, 116 Agassi, Lake, 285 Australopithecines (robust), 286 Ahmarian, 80 Azilian, 74 Ailuropoda melanoleuca fovealis, 35 Airstrip Mound site, 136 Bacsonian, 188, 192, 194 Altai Mountains, 50, 51, 94, 103 Balobok rock-shelter, 159 Altamira, 73 Ban Don Mun, 54 Amyda cartilaginea, 218, 230 Ban Lum Khao, 164, 165 Amyda sp., 37 Ban Mae Tha, 54 Anderson, D.D., 111, 201 Ban Rai, 203 Anorrhinus galeritus, 219 Banteng. See Bos cf. javanicus Anthracoceros coronatus, 219 Banyan Valley Cave, 201 Anthracoceros malayanus, 219 Barranco Leon,´ 29 Anthropocene, 8, 9, 274, 286, 289 BAT 1, 173, 174 Aq Kupruk, 104, 105 BAT 2, 173 Arboreal-adapted taxa, 96, 110, 111, 113, 122, 151, 152, Bat hawk. -

Holen Et Al. Reply Replying to J

BRIEF COMMUNICATIONS ARISING Contesting early archaeology in California ARISING FROM S. R. Holen et al. Nature 544, 479–483 (2017); doi:10.1038/nature22065 The peopling of the Americas is a topic of ongoing scientific interest 24,000-year-old Inglewood Mammoth Site (IMS), Maryland, USA. and rigorous debate1,2. Holen et al.3 add to these discussions with their As at the CM site, the IMS contains the remains of a single juvenile recent report of a 130,000-year-old archaeological site in southern proboscidean recovered in situ from a sealed deposit of sandy clays California, USA: the Cerutti Mastodon (CM) site, which includes the with pebbles and cobbles6. Haynes6 provides descriptions and images fragmentary remains of a single mastodon (Mammut americanum), of curvilinear and spiral ‘green-bone’ fractures on cranial, axial and spatially associated stone cobbles, and associated lithic debris that appendicular specimens. Some of these fractures are recent in origin, they claim indicates prehistoric hominin activity. In sharp contrast, we probably related to heavy earthmoving equipment working on-site6. contend that the CM record is more parsimoniously explained as the Other damage may reflect perimortem injuries sustained by the result of common geological and taphonomic processes, and does not mammoth. No evidence of prehistoric hominin activities are noted indicate prehistoric hominin involvement. Whereas further investiga- or suspected for the site. Post-burial bone notches, impact points and tions may yet identify unambiguous evidence of hominins in California impact scratches occurred on a number of specimens. around 130,000 years ago, we urge caution in interpreting the current We report a similar record of fractured proboscidean bones at the record. -

0205683290.Pdf

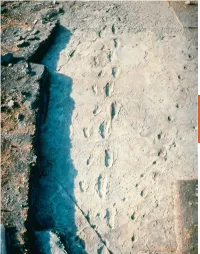

Hominin footprints preserved at Laetoli, Tanzania, are about 3.6 million years old. These individuals were between 3 and 4 feet tall when standing upright. For a close-up view of one of the footprints and further information, go to the human origins section of the website of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/ humanorigins/ha/laetoli.htm. THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY AND CULTURE 2 the BIG questions v What do living nonhuman primates tell us about OUTLINE human culture? Nonhuman Primates and the Roots of Human Culture v Hominin Evolution to Modern What role did culture play Humans during hominin evolution? Critical Thinking: What Is Really in the Toolbox? v How has modern human Eye on the Environment: Clothing as a Thermal culture changed in the past Adaptation to Cold and Wind 12,000 years? The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of Cities and States Lessons Applied: Archaeology Findings Increase Food Production in Bolivia 33 Substantial scientific evidence indicates that modern hu- closest to humans and describes how they provide insights into mans have evolved from a shared lineage with primate ances- what the lives of the earliest human ancestors might have been tors between 4 and 8 million years ago. The mid-nineteenth like. It then turns to a description of the main stages in evolu- century was a turning point in European thinking about tion to modern humans. The last section covers the develop- human origins as scientific thinking challenged the biblical ment of settled life, agriculture, and cities and states. -

A Contextual Review of the Carnivora of Kanapoi

A contextual review of the Carnivora of Kanapoi Lars Werdelin1* and Margaret E. Lewis2 1Department of Palaeobiology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, S-10405 Stockholm, Swe- den; [email protected] 2Biology Program, School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Stockton University, 101 Vera King Farris Drive, Galloway, NJ 08205, USA; [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract The Early Pliocene is a crucial time period in carnivoran evolution. Holarctic carnivoran faunas suffered a turnover event at the Miocene-Pliocene boundary. This event is also observed in Africa but its onset is later and the process more drawn-out. Kanapoi is one of the earliest faunas in Africa to show evidence of a fauna that is more typical Pliocene than Miocene in character. The taxa recovered from Kanapoi are: Torolutra sp., Enhydriodon (2 species), Genetta sp., Helogale sp., Homotherium sp., Dinofelis petteri, Felis sp., and Par- ahyaena howelli. Analysis of the broader carnivoran context of which Kanapoi is an example shows that all these taxa are characteristic of Plio-Pleistocene African faunas, rather than Miocene ones. While some are still extant and some went extinct in the Early Pleistocene, Parahyaena howelli is unique in both originating and going extinct in the Early Pliocene. Keywords: Africa, Kenya, Miocene, Pliocene, Pleistocene, Carnivora Introduction Dehghani, 2011; Werdelin and Lewis, 2013a, b). In Kanapoi stands at a crossroads of carnivoran this contribution we will investigate this pattern and evolution. The Miocene –Pliocene boundary (5.33 its significance in detail. Ma: base of the Zanclean Stage; Gradstein et al., 2012) saw a global turnover among carnivores (e.g., Material and methods Werdelin and Turner, 1996). -

The Fossil Proboscideans of Bulgaria and the Importance of Some Bulgarian Finds – a Brief Review

Historia naturalis bulgarica, The fossil proboscideans of Bulgaria 139 16: 139-150, 2004 The fossil proboscideans of Bulgaria and the importance of some Bulgarian finds – a brief review Georgi N. MARKOV MARKOV G. 2004. The fossil proboscideans of Bulgaria and the importance of some Bulgarian finds – a brief review. – Historia naturalis bulgarica, 16: 139-150. Abstract. The paper summarizes briefly the current data on Bulgarian fossil proboscideans, revised by the author. Finds of special interest and importance for different problems of proboscideanology are discussed, with some paleozoogeographical notes. Key words: Proboscidea, Neogene, Bulgaria, Systematics Introduction The following text is a brief summary of the results obtained during a PhD research (2000-2003; thesis in preparation) on the fossil proboscideans of Bulgaria. Various Bulgarian collections stock several hundred specimens of fossil proboscideans from more than a hundred localities in the country. BAKALOV & NIKOLOV (1962; 1964) summarized most of the finds collected from the beginning of the 20th century to the 1960s, the first of the cited papers dealing with deinotheres, mammutids and gomphotheres sensu lato, the second – with elephantids. Sporadic publications from the 1970s have added more material. During the 1980s and the 1990s there were practically no studies by Bulgarian authors describing new material or revising the proboscidean fossils already published. Bulgarian material has been discussed by TASSY (1983; 1999), TOBIEN (1976; 1978; 1986; 1988), METZ- MULLER (1995; 1996a,b; 2000), and more recently by MARKOV et al. (2002), HUTTUNEN (2002a,b), HUTTUNEN & GÖHLICH (2002), LISTER & van ESSEN (2003), and MARKOV & SPASSOV (2003a,b). During the last two decades, a large amount of unpublished material was gathered, and many of the previously published finds needed a serious revision.