Holen Et Al. Reply Replying to J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Male Strategies and Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology

J. F. O’Connell Male strategies and Plio-Pleistocene Department of Anthropology, archaeology1 270 South 1400 East, University of Utah, Salt Lake Archaeological data are frequently cited in support of the idea that big City, Utah 84112, U.S.A. game hunting drove the evolution of early Homo, mainly through its E-mail: role in offspring provisioning. This argument has been disputed on [email protected] two grounds: (1) ethnographic observations on modern foragers show that although hunting may contribute a large fraction of the overall K. Hawkes diet, it is an unreliable day-to-day food source, pursued more Department of Anthropology, for status than subsistence; (2) archaeological evidence from the 270 South 1400 East, Plio-Pleistocene, coincident with the emergence of Homo can be read University of Utah, Salt Lake to reflect low-yield scavenging, not hunting. Our review of the City, Utah 84112, U.S.A. archaeology yields results consistent with these critiques: (1) early E-mail: humans acquired large-bodied ungulates primarily by aggressive [email protected] scavenging, not hunting; (2) meat was consumed at or near the point of acquisition, not at home bases, as the hunting hypothesis requires; K. D. Lupo (3) carcasses were taken at highly variable rates and in varying Department of Anthropology, degrees of completeness, making meat from big game an even less Washington State University, reliable food source than it is among modern foragers. Collectively, Pullman, Washington 99164, Plio-Pleistocene site location and assemblage composition are con- U.S.A. sistent with the hypothesis that large carcasses were taken not for E-mail: [email protected] purposes of provisioning, but in the context of competitive male displays. -

South Bay Historical Society Bulletin December 2017 Issue No

South Bay Historical Society Bulletin December 2017 Issue No. 17 First People ocean and from the broad Tijuana River lagoon that existed back then. Also found was Coso Who were the First People? Where did they obsidian from Inyo County over 300 miles away, live? How were they able to survive? At our showing that these people had an extensive meeting on Monday, December 11 at 6 pm in trade network.2 the Chula Vista Library, Dennis Gallegos will answer these questions. His new book, First The First People may have come to the South People: A Revised Chronology for San Diego Bay long before those found at Remington Hills. County, examines the archaeological evidence Scientists from the San Diego Natural History going back to the end of the Ice Age 10,000 Museum have examined mastodon bones years ago. The ancestors of todayʼs Kumeyaay may have come down the coast from the shrinking Bering land bridge. Ancestors who spoke the ancient Hokan language may have come from the east, overland from the receding waters of the Great Basin. These early people (Californiaʼs first migrants) were called the “Scraper-Makers” by the pioneering archaeologist Malcolm Rogers in the 1920s.1 The name came from the stone tools that Rogers discovered at many sites in San Diego County, from the San Dieguito River in the north to the Otay River in the south. Rogers described their culture as the “San Dieguito pattern” based on his research at the Harris site near Lake Hodges on the San Dieguito River. This same cultural pattern and stone tools have been found at the Remington Hills site in western Otay Mesa. -

Hunting and Nuclear Families F 683 Wet Through Early Dry

Current Anthropology Volume 42, Number 5, December 2001 ᭧ 2001 by The Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. All rights reserved 0011-2304/2001/4205-0004$3.00 Among most ethnographically known hunter-gatherers, Hunting and Nuclear hunting is men’s work, women marry hunters, and spouses establish households in which, among other things, all sometimes eat meat. This constellation of fea- Families tures is widely assumed to show that nuclear families are units of common economic interest, with labor di- vided by sex to serve familial welfare (Murdock 1949, Some Lessons from the Hadza Sahlins 1972). Meat sharing beyond the household is viewed as exchange, successful hunters insuring against 1 about Men’s Work the unpredictability of hunting to provision dependents by trading surplus meat when they are successful for shares to be repaid when fortunes are reversed. This by K. Hawkes, J. F. O’Connell, model underpins the most influential scenario of human evolution, in which an array of distinctively human fea- and N. G. Blurton Jones tures is presumed to evolve as a consequence of males’ hunting and sharing meat to support their mates and offspring (Washburn and DeVore 1961; Washburn and Lancaster 1968; Isaac 1978; Hill 1982; Lancaster and Lan- caster 1983, 1987; Ridley 1996; Pinker 1997; Kaplan et Hadza hunter-gatherers display economic and social features usu- al. 2000). ally assumed to indicate the dependence of wives and children on provisioning husbands and fathers. The wives and children of Hadza foragers, living in the tropical savanna along the better Hadza hunters have been found to be better-nourished, East African Rift, face many of the ecological constraints consistent with the assumption that men hunt to provision their assumed to favor reliance on hunters for household pro- families. -

Before the Massive Modern Human Dispersal Into Eurasia a 55,000

Quaternary International xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Before the massive modern human dispersal into Eurasia: A 55,000-year-old partial cranium from Manot Cave, Israel ∗ Gerhard W. Webera, , Israel Hershkovitzb,c, Philipp Gunzd, Simon Neubauerd, Avner Ayalone, Bruce Latimerf, Miryam Bar-Matthewse, Gal Yasure, Omry Barzilaig, Hila Mayb,c a Department of Anthropology & Core Facility for Micro-Computed Tomography, University of Vienna, Althanstr. 14, A-1090, Vienna, Austria b Department of Anatomy and Anthropology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, PO Box 39040, 6997801, Tel Aviv, Israel c Dan David Center for Human Evolution & Biohistory Research, Shmunis Family Anthropology Institute, Sackler Fac. of Med., Tel Aviv University, PO Box 39040, 6997801, Tel Aviv, Israel d Department of Human Evolution, Max-Planck-Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Deutscher Platz 6, D-04103, Leipzig, Germany e Geological Survey of Israel, Yisha'ayahu Leibowitz St. 32, Jerusalem, Israel f Departments of Anatomy and Orthodontics, Case Western Reserve University, 44106, Cleveland, OH, USA g Israel Antiquities Authority, PO Box 586, 91004, Jerusalem, Israel ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Genetic and archaeological models predict that African modern humans successfully colonized Eurasia between Early modern humans 60,000 and 40,000 years before present (ka), replacing all other forms of hominins. While there is good evidence Neanderthals for the first arrival in Eurasia around 50-45ka, the fossil record is extremely scarce with regard to earlier re- Out-of-Africa presentatives. A partial calvaria discovered at Manot Cave (Western Galilee, Israel) dated to > 55 ka by ur- Modern human migration anium–thorium dating was recently described. -

The Demise of Homo Erectus and the Emergence of a New Hominin Lineage in the Middle Pleistocene (Ca

Man the Fat Hunter: The Demise of Homo erectus and the Emergence of a New Hominin Lineage in the Middle Pleistocene (ca. 400 kyr) Levant Miki Ben-Dor1, Avi Gopher1, Israel Hershkovitz2, Ran Barkai1* 1 Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel, 2 Department of Anatomy and Anthropology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Dan David Laboratory for the Search and Study of Modern Humans, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel Abstract The worldwide association of H. erectus with elephants is well documented and so is the preference of humans for fat as a source of energy. We show that rather than a matter of preference, H. erectus in the Levant was dependent on both elephants and fat for his survival. The disappearance of elephants from the Levant some 400 kyr ago coincides with the appearance of a new and innovative local cultural complex – the Levantine Acheulo-Yabrudian and, as is evident from teeth recently found in the Acheulo-Yabrudian 400-200 kyr site of Qesem Cave, the replacement of H. erectus by a new hominin. We employ a bio-energetic model to present a hypothesis that the disappearance of the elephants, which created a need to hunt an increased number of smaller and faster animals while maintaining an adequate fat content in the diet, was the evolutionary drive behind the emergence of the lighter, more agile, and cognitively capable hominins. Qesem Cave thus provides a rare opportunity to study the mechanisms that underlie the emergence of our post-erectus ancestors, the fat hunters. Citation: Ben-Dor M, Gopher A, Hershkovitz I, Barkai R (2011) Man the Fat Hunter: The Demise of Homo erectus and the Emergence of a New Hominin Lineage in the Middle Pleistocene (ca. -

Neanderthal Predation and the Bottleneck Speciation of Modern Humans

Them and Us: Neanderthal predation and the bottleneck speciation of modern humans Danny Vendramini* *Independent scholar. Correspondence to: PO. Box 924 Glebe. Sydney, NSW. 2037 Australia. Ph: 612-9550 9682. Email: [email protected] Keywords: Human evolution, Neanderthals, Levant, Upper Palaeolithic, predation, natural selection, modern human origins. Abstract Based on a reassessment of Neanderthal behavioural ecology it is argued argues that the emergence of behaviourally modern humans was the consequence of systemic Neanderthal predation of Middle Paleolithic humans in the East Mediterranean Levant between 100 and 45 thousand years BP. ‘Neanderthal predation theory’ proposes intraguild predation, sexual predation, hybridisation, lethal raiding and coalitionary killing gradualistically reduced the Levantine human population, resulting in a population bottleneck <50 Kya and precipitating the selection of anti-Neanderthal adaptations. Sexual predation generated robust selection pressure for an alternate human mating system based on, private copulation, concealed ovulation, menstrual synchrony, habitual washing, scent concealment, mate guarding, enforced female fidelity, incest avoidance and long-term pair bonding. Simultaneously, intraguild predation, lethal raiding and coalitionary killing generated selection pressure for strategic adaptations, including cognitive fluidity, male aggression, language capacity, creativity, increased athleticism, enhanced semantic memory, group loyalty, male risk-taking, capacity to form strategic coalitions, -

A Review of Archaeological Dating Efforts at Cave and Rockshelter Sites in the Indonesian Archipelago

A REVIEW OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATING EFFORTS AT CAVE AND ROCKSHELTER SITES IN THE INDONESIAN ARCHIPELAGO Hendri A. F. Kaharudin1,2, Alifah3, Lazuardi Ramadhan4 and Shimona Kealy2,5 1School of Archaeology and Anthropology, College of Arts and Social Sciences, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2600, Australia 2Archaeology and Natural History Department, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2600 Australia 3Balai Arkeologi Yogyakarta, JL. Gedongkuning No. 174, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 4Departemen Arkeologi, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, 55281 Indonesia 5ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2600 Australia Corresponding author: Hendri A. F. Kaharudin, [email protected] Keywords: initial occupation, Homo sapiens, Island Southeast Asia, Wallacea, absolute dating ABSTRACT ABSTRAK In the last 35 years Indonesia has seen a sub- Sejak 35 tahun terakhir, Indonesia mengalami stantial increase in the number of dated, cave peningkatan dalam usaha pertanggalan situs and rockshelter sites, from 10 to 99. Here we gua dan ceruk dari 10 ke 99. Di sini, kami review the published records of cave and meninjau ulang data gua dan ceruk yang telah rockshelter sites across the country to compile a dipublikasikan untuk menghimpun daftar yang complete list of dates for initial occupation at lengkap terkait jejak hunian tertua di setiap si- each site. All radiocarbon dates are calibrated tus. Kami melakukan kalibrasi terhadap setiap here for standardization, many of them for the pertanggalan radiocarbon sebagai bentuk first time in publication. Our results indicate a standardisasi. Beberapa di antaranya belum clear disparity in the distribution of dated ar- pernah dilakukan kalibrasi sebelumnya. -

Homo Habilis, the 1470 and 1813 Groups, the Ledi-Geraru Homo

Early Homo: Homo habilis, the 1470 and 1813 groups, the Ledi-Geraru Homo CHARLES J. VELLA, PH.D 2019 Abbreviations of Locales AMNH American Museum of Natural History DK Douglas Korongo (a locality at Olduvai Gorge) Stw Sterkfontein site (UW designation) FLK Frida Leakey Korongo (a locality at Olduvai Gorge) TM Transvaal Museum FLKNN FLK North—North (a locality at Olduvai Gorge) KBS Kay Behrensmeyer Site (at East Turkana) UW University of the Witwatersrand KNM-ER Kenya National Museums—East Rudolf KNM-WT Kenya National Museums—West Turkana LH Laetoli Hominid MLD Makapansgat Limeworks Deposit MNK Mary Nicol Korongo (a locality at Olduvai Gorge) NMT National Museum of Tanzania NMT-WN National Museum of Tanzania—West Natron NMT National Museum of Ethiopia NMT-WN National Museum of Ethiopia—West Natron OH Olduvai Hominid SK Swartkrans Sts Sterkfontein site (TM designation) Charles Darwin, “Descent of Man” (1871, p. 230): “….it would be impossible to fix on any point when the term “man” ought to be used…” • Paleontologically, whether a fossil is Homo turns out to be very complicated. Homo erectus Homo Homo rudolfensis heidelbergensis Australopithecus Homo sapiens africanus Three-dimensional skull casts of early hominins (left to right): Australopithecus africanus, 2.5 Ma from Sterkfontein in South Africa; Homo rudolfensis, 1.9 Ma from Koobi Fora, Kenya; Homo erectus, 1 Ma from Java, Indonesia; Homo heidelbergensis, 350 Ka from Thessalonika, Greece; and Homo sapiens, 4,800 years old from Fish Hoek, South Africa. Credit: Smithsonian Institution. 10 Current Species of Genus Homo 1. Homo habilis (& Homo rudolfensis) 2. Homo erectus (Asian) [ & Homo ergaster (African)] 3. -

A Visual and Contextual Analysis of Four Paleolithic Painted Caves in Southwest France (Dordogne)

Looking at caves from the bottom-up: a visual and contextual analysis of four Paleolithic painted caves in Southwest France (Dordogne) by Suzanne Natascha Villeneuve B.A. (Hons.) Simon Fraser University, 2003 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology © Suzanne Villeneuve 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Looking at caves from the bottom-up: a visual and contextual analysis of four Paleolithic painted caves in Southwest France (Dordogne) by Suzanne Natascha Villeneuve B.A. (Hons.) Simon Fraser University, 2003 Supervisory Committee: Dr. April Nowell, Supervisor (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Quentin Mackie, Committee Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Nicholas Rolland, Committee Member (Department of Anthropology) iii SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Dr. April Nowell, Supervisor (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Quentin Mackie, Committee Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Nicholas Rolland, Committee Member (Department of Anthropology) ABSTRACT A century of hypotheses concerning Paleotlithic cave use has focused either on individual activities (such as vision quests or shamanistic visits) or group activities such as initiations. This thesis proposes and tests systematic criteria for assessing whether painted caves were locations of group or individual ritual activity in four caves in the Dordogne Region of Southwest France (Bernifal, Font-de-Gaume, Combarelles, and Villars). Resolving this issue provides an important foundation for examining more complex questions such as the exclusivity/inclusivity of groups using caves and their possible roles in the development and maintenance of inequalities in the Upper Paleolithic. -

An Artifact of Human Behavior? Paleoindian Endscraper Breakage In

PERRONE, ALYSSA R., M.A., MAY 2020 ANTHROPOLOGY AN ARTIFACT OF HUMAN BEHAVIOR? PALEOINDIAN ENDSCRAPER BREAKAGE IN MIDWESTERN AND GREAT LAKES NORTH AMERICA (67 pp.) Thesis Advisor: Metin I. Eren Endscrapers, comprising the most abundant tool class at Eastern North American Paleoindian sites, are flaked stone specimens predominately used for scraping hides. They are broken in high frequencies at Paleoindian sites, a pattern that has been attributed to Paleoindian use. However, previous experimental and ethnographic research on endscrapers suggests they are difficult to break. We present a series of replication experiments assessing the amount of force required for endscraper breakage, as well as the amount of force generated during human use. We also analyze which morphometric variable best predicts the breakage force. Our results demonstrate that human use comes nowhere close to breakage force, which is best predicted by endscraper thickness. Finally, we examine an actual Paleoindian endscraper assemblage, concluding that humans were not the cause of breakage. Taphonomic factors such as modern plowing, or trampling, are a much better potential explanation for the high breakage frequencies present Paleoindian sites. AN ARTIFACT OF HUMAN BEHAVIOR? PALEOINDIAN ENDSCRAPER BREAKAGE IN MIDWESTERN AND GREAT LAKES NORTH AMERICA A Thesis Submitted To Kent State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Alyssa R. Perrone May 2020 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published material Thesis written by Alyssa R. Perrone B.A., University of Akron, 2018 M.A., Kent State University, 2020 Approved by ___________________________________, Advisor Metin I. Eren, Ph.D. ___________________________________, Chair, Department of Anthropology Mary Ann Raghanti, Ph.D. -

Language and Modern Human Origins

YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 3691-126 (1993) Language and Modern Human Origins L.A. SCHEPARTZ Department of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 KEY WORDS Language, Homo sapiens, Human origins, Speech ABSTRACT The evolution of anatomically modern humans is fre- quently linked to the development of complex, symbolically based language. Language, functioning as a system of cognition and communication, is sug- gested to be the key behavior in later human evolution that isolated modern humans from their ancestors. Alternatively, other researchers view com- plex language as a much earlier hominid capacity, unrelated to the origin of anatomically modern Homo sapiens. The validity of either perspective is contingent upon how language is defined and how it can be identified in the paleoanthropological record. In this analysis, language is defined as a sys- tem with external aspects relating to speech production and internal as- pects involving cognition and symbolism. The hypothesis that complex lan- guage was instrumental in modern human origins is then tested using data from the paleontological and archaeological records on brain volume and structure, vocal tract form, faunal assemblage composition, intra-site diver- sification, burial treatment, ornamentation and art. No data are found to support linking the origin of modern humans with the origin of complex language. Specifically, there are no data suggesting any major qualitative changes in language abilities corresponding with the 200,000-100,000 BP dates for modern Homo sapiens origins proposed by single origin models or the 40,000-30,000 BP period proposed as the time for the appearance of modern Homo sapiens in Western Europe. -

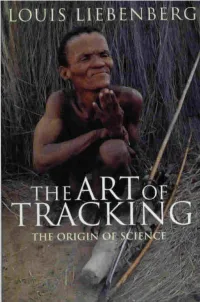

The Art of Tracking the Origin of Science

The Art of Tracking Tbe Origin of Science Louis Liebenberg David Philip First published 1990 in southern Africa by David Philip Publishers (Pty) Ltd 208 Werdmuller Centre, Claremont 7700, South Africa text © Louis Liebenherg illustrations © Louis Liebenherg All rights reserved ISBN 0 R6486 131 1 Typesetting hy Desktop Design cc, Shortmarket Street. Cape Town Printed hy Creda Press. Solan Road. Cape Town Contents Introduction . v Part I: The Evolution of Hunter-Gatherer Subsistence 1 1 Hominid Evolution . 3 2 The Evolution of Hominid Subsistence 11 3 The Evolution of Tracking . 29 4 The Origin of Science ,tnd Art 41 Part U: Hunter-Gatherers of the Kalahari ....... -l9 S Hunter-Gatherer Subsi�tence . 51 6 Scientific Knowledge of Spoor and Animal Behaviour 69 .... Non-scientific Aspects of Hunting . 93 Part lli: The Fundamentals of Tracking . 99 8 Principles of Tr.tcking 101 9 Classification of Signs 111 10 Spoor Interpretation 121 11 Scientific Research Programmes 153 References 167 Index . 173 Introduction According to a popular misconception, nature is "like an open book" to the expert tracker and such an expert needs only enough skill to "read everything that is written in the sand". A more appropriate analogy would be that the expert tracker must be able to "read between the lines". Trackers themselves cannot read everything in the sand. Rather, they must be able to read into the sand. To interpret tracks and signs trackers must project themselves into the position of the animal in order to create a hypothetical explanation of what the animal was doing. Tracking is not strictly empirical, since it also involves the tracker's imagination.