Schizophrenia Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HALDOL Brand of Haloperidol Injection (For Immediate Release) WARNING Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia

HALDOL® brand of haloperidol injection (For Immediate Release) WARNING Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Analyses of seventeen placebo-controlled trials (modal duration of 10 weeks), largely in patients taking atypical antipsychotic drugs, revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients of between 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death in placebo-treated patients. Over the course of a typical 10-week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug-treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group. Although the causes of death were varied, most of the deaths appeared to be either cardiovascular (e.g., heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (e.g., pneumonia) in nature. Observational studies suggest that, similar to atypical antipsychotic drugs, treatment with conventional antipsychotic drugs may increase mortality. The extent to which the findings of increased mortality in observational studies may be attributed to the antipsychotic drug as opposed to some characteristic(s) of the patients is not clear. HALDOL Injection is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis (see WARNINGS). DESCRIPTION Haloperidol is the first of the butyrophenone series of major antipsychotics. The chemical designation is 4-[4-(p-chlorophenyl)-4-hydroxypiperidino] 4’-fluorobutyrophenone and it has the following structural formula: HALDOL (haloperidol) is available as a sterile parenteral form for intramuscular injection. The injection provides 5 mg haloperidol (as the lactate) and lactic acid for pH adjustment between 3.0 – 3.6. -

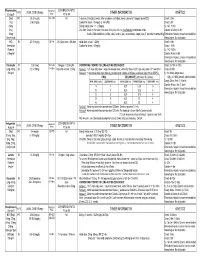

Medication Conversion Chart

Fluphenazine FREQUENCY CONVERSION RATIO ROUTE USUAL DOSE (Range) (Range) OTHER INFORMATION KINETICS Prolixin® PO to IM Oral PO 2.5-20 mg/dy QD - QID NA ↑ dose by 2.5mg/dy Q week. After symptoms controlled, slowly ↓ dose to 1-5mg/dy (dosed QD) Onset: ≤ 1hr 1mg (2-60 mg/dy) Caution for doses > 20mg/dy (↑ risk EPS) Cmax: 0.5hr 2.5mg Elderly: Initial dose = 1 - 2.5mg/dy t½: 14.7-15.3hr 5mg Oral Soln: Dilute in 2oz water, tomato or fruit juice, milk, or uncaffeinated carbonated drinks Duration of Action: 6-8hr 10mg Avoid caffeinated drinks (coffee, cola), tannics (tea), or pectinates (apple juice) 2° possible incompatibilityElimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 5mg/ml soln Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable HCl IM 2.5-10 mg/dy Q6-8 hr 1/3-1/2 po dose = IM dose Initial dose (usual): 1.25mg Onset: ≤ 1hr Immediate Caution for doses > 10mg/dy Cmax: 1.5-2hr Release t½: 14.7-15.3hr 2.5mg/ml Duration Action: 6-8hr Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable Decanoate IM 12.5-50mg Q2-3 wks 10mg po = 12.5mg IM CONVERTING FROM PO TO LONG-ACTING DECANOATE: Onset: 24-72hr (4-72hr) Long-Acting SC (12.5-100mg) (1-4 wks) Round to nearest 12.5mg Method 1: 1.25 X po daily dose = equiv decanoate dose; admin Q2-3wks. Cont ½ po daily dose X 1st few mths Cmax: 48-96hr 25mg/ml Method 2: ↑ decanoate dose over 4wks & ↓ po dose over 4-8wks as follows (accelerate taper for sx of EPS): t½: 6.8-9.6dy (single dose) ORAL DECANOATE (Administer Q 2 weeks) 15dy (14-100dy chronic administration) ORAL DOSE (mg/dy) ↓ DOSE OVER (wks) INITIAL DOSE (mg) TARGET DOSE (mg) DOSE OVER (wks) Steady State: 2mth (1.5-3mth) 5 4 6.25 6.25 0 Duration Action: 2wk (1-6wk) Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 10 4 6.25 12.5 4 Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable 20 8 6.25 12.5 4 30 8 6.25 25 4 40 8 6.25 25 4 Method 3: Admin equivalent decanoate dose Q2-3wks. -

Schizophrenia Care Guide

August 2015 CCHCS/DHCS Care Guide: Schizophrenia SUMMARY DECISION SUPPORT PATIENT EDUCATION/SELF MANAGEMENT GOALS ALERTS Minimize frequency and severity of psychotic episodes Suicidal ideation or gestures Encourage medication adherence Abnormal movements Manage medication side effects Delusions Monitor as clinically appropriate Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Danger to self or others DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA/EVALUATION (PER DSM V) 1. Rule out delirium or other medical illnesses mimicking schizophrenia (see page 5), medications or drugs of abuse causing psychosis (see page 6), other mental illness causes of psychosis, e.g., Bipolar Mania or Depression, Major Depression, PTSD, borderline personality disorder (see page 4). Ideas in patients (even odd ideas) that we disagree with can be learned and are therefore not necessarily signs of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a world-wide phenomenon that can occur in cultures with widely differing ideas. 2. Diagnosis is made based on the following: (Criteria A and B must be met) A. Two of the following symptoms/signs must be present over much of at least one month (unless treated), with a significant impact on social or occupational functioning, over at least a 6-month period of time: Delusions, Hallucinations, Disorganized Speech, Negative symptoms (social withdrawal, poverty of thought, etc.), severely disorganized or catatonic behavior. B. At least one of the symptoms/signs should be Delusions, Hallucinations, or Disorganized Speech. TREATMENT OPTIONS MEDICATIONS Informed consent for psychotropic -

HALDOL Decanoate 50 (Haloperidol)

HALDOL® Decanoate 50 (haloperidol) HALDOL® Decanoate 100 (haloperidol) For IM Injection Only WARNING Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Analyses of seventeen placebo-controlled trials (modal duration of 10 weeks), largely in patients taking atypical antipsychotic drugs, revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients of between 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death in placebo-treated patients. Over the course of a typical 10-week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug-treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group. Although the causes of death were varied, most of the deaths appeared to be either cardiovascular (e.g., heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (e.g., pneumonia) in nature. Observational studies suggest that, similar to atypical antipsychotic drugs, treatment with conventional antipsychotic drugs may increase mortality. The extent to which the findings of increased mortality in observational studies may be attributed to the antipsychotic drug as opposed to some characteristic(s) of the patients is not clear. HALDOL Decanoate is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis (see WARNINGS). DESCRIPTION Haloperidol decanoate is the decanoate ester of the butyrophenone, HALDOL (haloperidol). It has a markedly extended duration of effect. It is available in sesame oil in sterile form for intramuscular (IM) injection. The structural formula of haloperidol decanoate, 4-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-[4-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxobutyl]-4 piperidinyl decanoate, is: Haloperidol decanoate is almost insoluble in water (0.01 mg/mL), but is soluble in most organic solvents. -

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (Also Belong to Psychiatric Medication Category) • Codeine (In 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • codeine (in 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No. 1/2/3/4, Fiorinal® C, Benzodiazepines Codeine Contin, etc.) • heroin • alprazolam (Xanax®) • hydrocodone (Hycodan®, etc.) • chlordiazepoxide (Librium®) • hydromorphone (Dilaudid®) • clonazepam (Rivotril®) • methadone • diazepam (Valium®) • morphine (MS Contin®, M-Eslon®, Kadian®, Statex®, etc.) • flurazepam (Dalmane®) • oxycodone (in Oxycocet®, Percocet®, Percodan®, OxyContin®, etc.) • lorazepam (Ativan®) • pentazocine (Talwin®) • nitrazepam (Mogadon®) • oxazepam ( Serax®) Alcohol • temazepam (Restoril®) Inhalants Barbiturates • gases (e.g. nitrous oxide, “laughing gas”, chloroform, halothane, • butalbital (in Fiorinal®) ether) • secobarbital (Seconal®) • volatile solvents (benzene, toluene, xylene, acetone, naptha and hexane) Buspirone (Buspar®) • nitrites (amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite and cyclohexyl nitrite – also known as “poppers”) Non-Benzodiazepine Hypnotics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • chloral hydrate • zopiclone (Imovane®) Other • GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) • Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM STIMULANTS Amphetamines Caffeine • dextroamphetamine (Dexadrine®) Methelynedioxyamphetamine (MDA) • methamphetamine (“Crystal meth”) (also has hallucinogenic actions) • methylphenidate (Biphentin®, Concerta®, Ritalin®) • mixed amphetamine salts (Adderall XR®) 3,4-Methelynedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) (also has hallucinogenic actions) Cocaine/Crack -

Behavioral Health Toolkit for Pcps Medicaid MP

Behavioral Health Toolkit For Primary Care and Behavioral Health Providers Page 1 of 34 Table of Contents I. Welcome 3 II. Contact Molina Healthcare 4 III. Assessment and Diagnosis of Mental Health Conditions 5 Depression Screening and Follow-up 6 Depression Screening 7 Substance Use Screening 8 Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) 9 IV. HEDIS Tips 10 Follow-up After Hospitalization for Mental Illness 11 Antidepressant Medication Management 12 Initiation and Engagement of Alcohol and Other Drug Dependence Treatment 14 Follow-Up Care for Children Prescribed ADHD Medication 16 Schizophrenia Management: Schizophrenia: Diabetes Screening 18 Schizophrenia: Diabetes Monitoring 20 Schizophrenia: Cardiovascular Monitoring 22 Schizophrenia: Antipsychotic Medication Adherence 24 Use of Multiple Concurrent Antipsychotics in Children and Adolescents 26 Metabolic Monitoring for Children and Adolescents on Antipsychotics 27 V. Risk Adjustment 28 Overview 29 Informational Sheet: Major Depression 30 Informational Sheet: Bipolar Disorder 31 Informational Sheet: Substance Use Disorders 32 Informational Sheet: Schizophrenia 33 Page 2 of 34 WELCOME: Thank you for being part of the Molina Healthcare network of providers. We designed this Behavioral Health Toolkit for Primary Care Providers to provide tools and guidance around management of Behavioral Health (mental health and substance use) conditions commonly seen in the primary care and community setting. Included in the toolkit are chapters addressing: • Assessment and Diagnosis of Mental Health -

Louisiana Fee-For-Service Medicaid Antipsychotics

Louisiana Fee-for-Service Medicaid Antipsychotics The Louisiana Uniform Prescription Drug Prior Authorization Form should be utilized to request: Authorization for non-preferred agents for recipients 6 years of age and older; AND Authorization for all preferred and non-preferred agents for recipients younger than 6 years of age; AND Authorization to exceed maximum daily dose/quantity limit for all ages. See full prescribing information for individual agents for details on the information below: *These agents have Black Box Warnings †These agents are subject to Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) under FDA safety regulations ‡ For long-acting injectable agents, it is required that the previous 60-day period of pharmacy claims show one of the following: Established tolerance to the oral formulation (as evidenced by a paid pharmacy claim for the oral formulation); OR Established therapy with the requested injectable agent (as evidenced by a paid pharmacy claim for the requested injectable agent) NOTE: Diagnosis code requirements apply to both preferred and non-preferred agents (see Table 1). Maximum daily dose edits (see Table 2), quantity limits (see Table 3), and other requirements at Point-of-Sale for select agents in this category may apply to both preferred and non-preferred agents. For additional information, see http://www.lamedicaid.com/provweb1/Pharmacy/pharmacyindex.htm. Oral Antipsychotics – Generic Name (Brand Example) * Amitriptyline/Perphenazine * Aripiprazole ODT; Oral Solution (Abilify®); Tablet (Abilify®) -

Efficacy and Safety of Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs

Efficacy and safety of atypical antipsychotic drugs (quetiapine, risperidone, aripiprazole and paliperidone) compared with placebo or typical antipsychotic drugs for treating refractory schizophrenia: overview of systematic reviews Eficácia e segurança dos antipsicóticos atípicos (quetiapina, risperidona, aripiprazol, paliperidona) em comparação com um placebo ou medicamentos antipsicóticos típicos no tratamento da esquizofrenia refratária: overview de revisão sistemática Tamara MelnikI, Bernardo Garcia SoaresII, Maria Eduarda dos Santos PugaIII, Álvaro Nagib AtallahIV Systematic review Brazilian Cochrane Centre, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (Unifesp), São Paulo, Brazil KEY WORDS: ABSTRACT Schizophrenia. Antipsychotic agents. CONTEXT AND OBJECTIVE: According to some cohort studies, the prevalence of refractory schizophrenia (RS) is 20-40%. Our aim was to evaluate the Dopamine antagonists. effectiveness and safety of aripiprazole, paliperidone, quetiapine and risperidone for treating RS. Aripiprazole [substance name]. METHODS: This was a critical appraisal of Cochrane reviews published in the Cochrane Library, supplemented with reference to more recent Quetiapine [substance name]. randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on RS. The following databases were searched: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (Medline) Risperidone. (1966-2009), Controlled Trials of the Cochrane Collaboration (2009, Issue 2), Embase (Excerpta Medica) (1980-2009), Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (Lilacs) (1982-2009). There was no language restriction. Randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews and meta-analyses evaluating atypical antipsychotics for treating RS were included. RESULTS: Seven Cochrane systematic reviews and 10 additional RCTs were included in this review. The data generally showed minor differences between the atypical antipsychotics evaluated and typical antipsychotics, regarding improvement in disease symptoms, despite better adherence to treatment with atypical antipsychotics. -

Antipsychotics-2020.Pdf

© Mind 2020 Antipsychotics Explains what antipsychotics are used for, how the medication works, possible side effects and information about withdrawal. If you require this information in Word document format for compatibility with screen readers, please email: [email protected] Contents What are antipsychotics? ...................................................................................................................... 2 Could antipsychotics help me? .............................................................................................................. 5 How to take antipsychotics safely ......................................................................................................... 9 What dosage of antipsychotics should I be on? .................................................................................. 15 Antipsychotics during pregnancy and breastfeeding ........................................................................... 17 What side effects can antipsychotics cause? ....................................................................................... 20 What is a depot injection? ................................................................................................................... 30 How can I compare different antipsychotics? ..................................................................................... 31 Can I come off antipsychotics? ............................................................................................................ 41 Alternatives to antipsychotics -

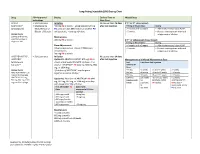

Long-Acting Injectable (LAI) Dosing Chart

Long-Acting Injectable (LAI) Dosing Chart Drug FDA-Approved Dosing Earliest Time to Missed Dose Indications Next Dose ABILIFY • Schizophrenia Initiation No sooner than 26 days If 2nd or 3rd dose missed: MAINTENA® • Maintenance 400 mg IM q month + aripiprazole 10-20 mg after last injection Timing of Missed Dose Dosing (aripiprazole)1 Monotherapy of PO daily x14 days OR if stable on another PO >4 weeks and <5 weeks • Administer missed dose ASAP. Bipolar 1 Disorder antipsychotic, + overlap x14 days >5 weeks • Restart next injection with oral Dosage Forms aripiprazole x 14 days. 300 mg and 400 mg Maintenance pre-filled syringe or 400 mg IM q month If 4th or subsequent doses missed: single-use vial Timing of Missed Dose Dosing Dose Adjustments >4 weeks and <6 weeks • Administer missed dose ASAP. Adverse reactions or known CYP2D6 poor >5 weeks • Restart next injection with oral metabolizers: aripiprazole x 14 days. 300 mg IM q month ARISTADA INITIO®, • Schizophrenia Initiation No sooner than 14 days ARISTADA® Option #1: ARISTADA INITIO® 675 mg IM x1 after last injection Management of a Missed Maintenance Dose (aripiprazole dose + aripiprazole 30 mg PO x1 dose + first Last Time Since Last Injection lauroxil)2,3 dose of *ARISTADA® IM (441 mg, 662 mg, 882 ARISTADA® mg, or 1064 mg) Dose Dosage Forms *first dose of ARISTADA® may be given 441 mg ≤6 weeks >6 and ≤7 weeks >7 weeks ARISTADA INITIO® 675 together or within 10 days* 662 mg ≤8 weeks >8 and ≤12 weeks >12 weeks mg pre-filled syringe 882 mg ≤8 weeks >8 and ≤12 weeks >12 weeks ARISTADA® 441 -

Name of Medicine

HALDOL® haloperidol decanoate NEW ZEALAND DATA SHEET 1. PRODUCT NAME HALDOL haloperidol decanoate 50 mg/mL Injection HALDOL CONCENTRATE haloperidol decanoate 100 mg/mL Injection 2. QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE COMPOSITION HALDOL 50 mg/ml Haloperidol decanoate 70.52 mg, equivalent to 50 mg haloperidol base, per millilitre. HALDOL CONCENTRATE 100 mg/ml Haloperidol decanoate 141.04 mg, equivalent to 100 mg haloperidol base, per millilitre. For a full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Injection (depot) HALDOL Injection (long acting) is a slightly amber, slightly viscous solution, free from visible foreign matter, filled in 1 mL amber glass ampoules. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications HALDOL is indicated for the maintenance therapy of psychoses in adults, particularly for patients requiring prolonged parenteral neuroleptic therapy. 4.2 Dose and method of administration Administration HALDOL should be administered by deep intramuscular injection into the gluteal region. It is recommended to alternate between the two gluteal muscles for subsequent injections. A 2 inch-long, 21 gauge needle is recommended. The maximum volume per injection site should not exceed 3 mL. The recommended interval between doses is 4 weeks. DO NOT ADMINISTER INTRAVENOUSLY. Patients must be previously stabilised on oral haloperidol before converting to HALDOL. Treatment initiation and dose titration must be carried out under close clinical supervision. The starting dose of HALDOL should be based on the patient's clinical history, severity of symptoms, physical condition and response to the current oral haloperidol dose. Patients must always be maintained on the lowest effective dose. CCDS(180302) Page 1 of 16 HALDOL(180712)ADS Dosage - Adults Table 1. -

Aripiprazole Long-Acting Injection(Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole Long-acting Injection Aripiprazole Long-acting Injection (Abilify Maintena, ARISTADA) National Drug Monograph October 2013; Addendum March 2016 VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives The purpose of VA PBM Services drug monographs is to provide a comprehensive drug review for making formulary decisions. These documents will be updated when new clinical data warrant additional formulary discussion. Documents will be placed in the Archive section when the information is deemed to be no longer current. Executive Summary: Aripiprazole long-acting intramuscular injection (LAIM) is sixth antipsychotic and the fourth second generation antipsychotic to be marketed in a long-acting injection formulation. LAIM antipsychotics on the VA National Formulary: haloperidol and fluphenazine decanoate; risperidone; and paliperidone. Aripiprazole LAIM has FDA label indication for the treatment of schizophrenia. The initial and usual maintenance dose of aripiprazole is 400 mg once a month. The dose can be reduced to 300 mg or 200 mg monthly based on drug interactions or tolerability. Patients should have established tolerability to aripiprazole before receipt of the LAIM formulation. Oral aripiprazole, 10-30 mg/day, or another oral antipsychotic must be continued for 2-weeks after the initial dose, and then discontinued. Aripiprazole LAIM’s efficacy and safety are based on experience with the oral formulation as well as pharmacokinetic trials and a 52-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The randomized trial was terminated early because the difference in time to relapse met a predetermined statistically significant threshold (p=0.001) favoring aripiprazole LAIM [HR 5.03, 95% CI 3.15-8.02].