Introduction to Old English.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tip #4 INFINITIVES 不定詞

Tip #4 INFINITIVES 不定詞 Basic Guidelines Infinitive means “without limit”, and is one of a group of three special word forms called “verbals”: Verbal Type Functions Forms 1) infinitive (不定詞) (weak) noun to + verb (to) verb to find help (to) do 2) gerund (動名詞) (strong) noun verb-ing finding 3) participle (分詞) adjective verb-ing verb-ed having verb-ed finding found having found acting acted having acted To conquer unknown areas of science is Taro’s desire. “to conquer” = noun(名詞) and is used as the subject of the sentence The desire to conquer unknown areas of science is Taro’s. “to conquer” = adjective(形容詞) and describes what kind of desire Taro desires to conquer unknown areas of science. “to conquer” = a noun phrase that actually functions to describe “desire” Writers too often misuse the infinitive because they were mistaught, or because the concepts were never learned properly. When thinking of the word “infinitive”, associate the word “infinity” “without limitations”. Infinitive use more commonly communicates uncertainty and doubt—though more psychologically—and is often used in situations in which logic and future possibilities are stressed. The gerund(V-ing 動名詞)—likely mistaught as well—stresses the concept of certainty much more the infinitive, and often refers to things done or finished in the past; thus, things that are known or certain. In short many writers overuse the infinitive in today’s technical, scientific, and even business writing; and use the gerund too little. For numerous reasons dating back to the 1980s, the gerund has become more and more frequently used for stressing facts or factual-like information. -

Not So Quirky: on Subject Case in Ice- Landic1

5 Not so Quirky: On Subject Case in Ice- landic 1 JÓHANNES GÍSLI JÓNSSON 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of subject case in Icelandic, extending and refining the observations of Jónsson (1997-1998) and some earlier work on this topic. It will be argued that subject case in Icelandic is more predictable from lexical semantics than previous studies have indicated (see also Mohanan 1994 and Narasimhan 1998 for a similar conclusion about Hindi). This is in line with the work of Jónsson (2000) and Maling (2002) who discuss various semantic generalizations about case as- signment to objects in Icelandic. This paper makes two major claims. First, there are semantic restrictions on non-nominative subjects in Icelandic which go far beyond the well- known observation that such subjects cannot be agents. It will be argued that non-nominative case is unavailable to all kinds of subjects that could be described as agent-like, including subjects of certain psych-verbs and intransitive verbs of motion and change of state. 1 I would like to thank audiences in Marburg, Leeds, York and Reykjavík and three anony- mous reviewers for useful comments. This study was supported by grants from the Icelandic Science Fund (Vísindasjóður) and the University of Iceland Research Fund (Rannsóknasjóður HÍ). New Perspectives in Case Theory. Ellen Brandner and Heike Zinsmeister (eds.). Copyright © 2003, CSLI Publications. 129 130 / JOHANNES GISLI JONSSON Second, the traditional dichotomy between structural and lexical case is insufficient in that two types of lexical case must be recognized: truly idio- syncratic case and what we might call semantic case. -

Old English: 450 - 1150 18 August 2013

Chapter 4 Old English: 450 - 1150 18 August 2013 As discussed in Chapter 1, the English language had its start around 449, when Germanic tribes came to England and settled there. Initially, the native Celtic inhabitants and newcomers presumably lived side-by-side and the Germanic speakers adopted some linguistic features from the original inhabitants. During this period, there is Latin influence as well, mainly through missionaries from Rome and Ireland. The existing evidence about the nature of Old English comes from a collection of texts from a variety of regions: some are preserved on stone and wood monuments, others in manuscript form. The current chapter focusses on the characteristics of Old English. In section 1, we examine some of the written sources in Old English, look at some special spelling symbols, and try to read the runic alphabet that was sometimes used. In section 2, we consider (and listen to) the sounds of Old English. In sections 3, 4, and 5, we discuss some Old English grammar. Its most salient feature is the system of endings on nouns and verbs, i.e. its synthetic nature. Old English vocabulary is very interesting and creative, as section 6 shows. Dialects are discussed briefly in section 7 and the chapter will conclude with several well-known Old English texts to be read and analyzed. 1 Sources and spelling We can learn a great deal about Old English culture by reading Old English recipes, charms, riddles, descriptions of saints’ lives, and epics such as Beowulf. Most remaining texts in Old English are religious, legal, medical, or literary in nature. -

I Am He … You Are Right Devotion

I am He … You are Right Devotion Read John 18:1-8 and Luke 22:70 – 23:1. Have you done or said anything recently that took a lot of courage? Do you know anyone who has? Is there something you should like to do or ought to do that you haven’t had the courage to face? Take a few minutes and discuss this in your group. Jesus is an unsurpassed example of the supreme measure of courage. He knew what He faced when He said, I am He (John 18:5b), to the group of men who had come to capture Him in the Garden of Gethsemane. He knew what humiliation and mockery would follow. Jesus also knew what the result would be when He answered Pilate’s question, Are you the king of the Jews (John 18:33b)? His reply would certainly result in extreme physical as well as emotional pain and ultimately death. Yet, He persevered. He was firm and steady. When we have a choice to make between truth and falsehood, the way of a committed Christian versus the way of the world, or of witnessing to our faith or keeping comfortably silent, what will our choice be? Challenges to today’s Christian may run the spectrum of minimal effect to major consequences, but they are nothing compared to the challenge of courage that Jesus faced. He stood and answered boldly and unwaveringly. When events in our lives call the unspoken or unspoken question of whether or not we are committed to Christ, let our words and actions make the courageous statement, “I am.” For all that Jesus courageously suffered on our behalf, overwhelming thankfulness must be our response. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Verses of Comfort and Faith

Verses of Comfort and Faith Isaiah 12:2-4 Behold, God is my salvation; I will trust, and not be afraid: for the Lord Jehovah is my strength and my song; he also is become my salvation. -Therefore with joy shall ye draw water out of the wells of salvation. -And in that day shall ye say, Praise the LORD, call upon his name, declare his doings among the people, make mention that his name is exalted. 25:1 O LORD, thou art my God; I will exalt thee, I will praise thy name; for thou hast done wonderful things; thy counsels of old are faithfulness and truth. 25:4 For thou hast been a strength to the poor, a strength to the needy in his distress, a refuge from the storm, a shadow from the heat, when the blast of the terrible ones is as a storm against the wall. 26:3-4 Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace, whose mind is stayed on thee: because he trusteth in thee. -Trust ye in the LORD for ever: for in the LORD JEHOVAH is everlasting strength: 40:28-31 Hast thou not known? hast thou not heard, that the everlasting God, the LORD, the Creator of the ends of the earth, fainteth not, neither is weary? there is no searching of his understanding. - He giveth power to the faint; and to them that have no might he increaseth strength. - Even the youths shall faint and be weary, and the young men shall utterly fall: - But they that wait upon the LORD shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with w i n g s as eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint. -

When to Start Receiving Retirement Benefits

2021 When to Start Receiving Retirement Benefits At Social Security, we’re often asked, “What’s the The following chart shows an example of how your best age to start receiving retirement benefits?” The monthly benefit increases if you delay when you start answer is that there’s not a single “best age” for receiving benefits. everyone and, ultimately, it’s your choice. The most important thing is to make an informed decision. Base Monthly Benefit Amounts Differ Based on the your decision about when to apply for benefits on Age You Decide to Start Receiving Benefits your individual and family circumstances. We hope This example assumes a benefit of $1,000 the following information will help you understand at a full retirement age of 66 and 10 months 1300 $1,253 how Social Security fits into your retirement decision. $1,173 $1,093 nt 1100 $1,013 ou $1,000 $944 $877 Am 900 Your decision is a personal one $811 $758 fit $708 Would it be better for you to start getting benefits ne 700 early with a smaller monthly amount for more years, y Be 500 or wait for a larger monthly payment over a shorter hl timeframe? The answer is personal and depends on nt several factors, such as your current cash needs, Mo your current health, and family longevity. Also, 0 consider if you plan to work in retirement and if you 62 63 64 65 66 66 and 67 68 69 70 have other sources of retirement income. You must 10 months also study your future financial needs and obligations, Age You Choose to Start Receiving Benefits and calculate your future Social Security benefit. -

The Ongoing Eclipse of Possessive Suffixes in North Saami

Te ongoing eclipse of possessive sufxes in North Saami A case study in reduction of morphological complexity Laura A. Janda & Lene Antonsen UiT Te Arctic University of Norway North Saami is replacing the use of possessive sufxes on nouns with a morphologically simpler analytic construction. Our data (>2K examples culled from >.5M words) track this change through three generations, covering parameters of semantics, syntax and geography. Intense contact pressure on this minority language probably promotes morphological simplifcation, yielding an advantage for the innovative construction. Te innovative construction is additionally advantaged because it has a wider syntactic and semantic range and is indispensable, whereas its competitor can always be replaced. Te one environment where the possessive sufx is most strongly retained even in the youngest generation is in the Nominative singular case, and here we fnd evidence that the possessive sufx is being reinterpreted as a Vocative case marker. Keywords: North Saami; possessive sufx; morphological simplifcation; vocative; language contact; minority language 1. Te linguistic landscape of North Saami1 North Saami is a Uralic language spoken by approximately 20,000 people spread across a large area in northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland. North Saami is in a unique situation as the only minority language in Europe under intense pressure from majority languages from two diferent language families, namely Finnish (Uralic) in the east and Norwegian and Swedish (Indo-European 1. Tis research was supported in part by grant 22506 from the Norwegian Research Council. Te authors would also like to thank their employer, UiT Te Arctic University of Norway, for support of their research. -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

Oksana's BU Paper

ACQUISITION of GENDER in RUSSIAN * Oksana Tarasenkova University of Connecticut 1 The Background In adult Russian grammar the gender feature of nouns is closely related to their declension class. Their relationship was a controversial question that evoked two opposing views regarding the way gender is represented in adult Russian grammar. The representatives of one view argue for gender to be derived from the noun declension class (Declension-to Gender account, Corbett 1982), while proponents of the opposite account argue for the reversed pattern, where the inflectional morphology can be predicted from the information on the noun gender along with a phonological cue (Gender-to-Declension account, Vinogradov 1960, Thelin 1975, Crockett 1976 among others). My goal is to focus on children’s acquisition of gender in Russian in order to compare these two major divisions of research. They provide different morphological analyses of gender forms in Russian; therefore this debate makes different predictions about the acquisition of gender by children. I tested these opposing predictions using children’s data gathered from an experiment to identify what exactly children rely on when assigning gender to nouns. The experiment results support the Declension-to-Gender view and provide evidence that children are significantly more successful at assigning gender to the novel nouns relying on the nominal declension paradigm rather than on the adjectival agreement. The way gender is represented in adults’ competence grammar might not necessarily be the correct model of children’s acquisition of gender. The child has to learn the gender of a significant number of nouns and extract the declensional paradigms first in order to then be able to learn and apply these redundancy rules for novel nouns. -

Pronouns: a Resource Supporting Transgender and Gender Nonconforming (Gnc) Educators and Students

PRONOUNS: A RESOURCE SUPPORTING TRANSGENDER AND GENDER NONCONFORMING (GNC) EDUCATORS AND STUDENTS Why focus on pronouns? You may have noticed that people are sharing their pronouns in introductions, on nametags, and when GSA meetings begin. This is happening to make spaces more inclusive of transgender, gender nonconforming, and gender non-binary people. Including pronouns is a first step toward respecting people’s gender identity, working against cisnormativity, and creating a more welcoming space for people of all genders. How is this more inclusive? People’s pronouns relate to their gender identity. For example, someone who identifies as a woman may use the pronouns “she/her.” We do not want to assume people’s gender identity based on gender expression (typically shown through clothing, hairstyle, mannerisms, etc.) By providing an opportunity for people to share their pronouns, you're showing that you're not assuming what their gender identity is based on their appearance. If this is the first time you're thinking about your pronoun, you may want to reflect on the privilege of having a gender identity that is the same as the sex assigned to you at birth. Where do I start? Include pronouns on nametags and during introductions. Be cognizant of your audience, and be prepared to use this resource and other resources (listed below) to answer questions about why you are making pronouns visible. If your group of students or educators has never thought about gender-neutral language or pronouns, you can use this resource as an entry point. What if I don’t want to share my pronouns? That’s ok! Providing space and opportunity for people to share their pronouns does not mean that everyone feels comfortable or needs to share their pronouns. -

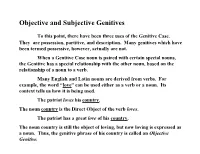

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium.